ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Evaluation of a lentil collection (Lens culinaris Medik) using morphological traits and digital phenotyping

Evaluación de una colección de lentejas (Lens culinaris Medik) utilizando caracteres morfológicos y fenotipado digital

María Andrea Espósito 1, 2, Ileana Gatti 2, 3, Carolina Julieta Bermejo 2, Enrique Luis Cointry 2

1 EEA INTA Oliveros. Ruta Nacional 11. Km 353. C. P. 2206. mesposi@unr.edu.ar

2 Universidad Nacional de Rosario. Facultad Ciencias Agrarias. Cátedra Mejoramiento Vegetal y Producción de Semillas. IICAR-CONICET. Campo Experimental. Villarino s/n. Zavalla. C.C. 14 (S2125ZAA).

3 Consejo de Investigaciones UNR (CIUNR). Universidad Nacional de Rosario.

Originales: Recepción: 04/10/2017 - Aceptación: 11/10/2018

ABSTRACT

The objective of this work was to evaluate 81 lentil cultivars using morphological traits and seed characteristics by digital phenotyping. Caliber (C) and the color traits luminosity (L), color coordinates a and b, and color index (CI) were measured and analyzed with appropriate software. Additionally, also yield (Y), plant height (PH) and days to flowering (DF) were measured. Highly significant differences between cultivars were found for all traits, while high broad sense heritability (H2B) for C (97%), CI (94%), a (93%) and L and b (83%) were found, indicating high genetic variability for these traits. Digital phenotyping showed to be a powerful tool for germplasm characterization along with field evaluation of agronomical traits. Principal Component Analysis and Cluster Analysis allows de identification of differentiated groups of cultivars with similar characteristics, leading to a more efficient use of the germplasm available as commercial cultivars or as parents in a breeding program. Among these groups, group 1 had 32 cultivars with highest C and group 2 had 21 cultivars with higher Y.

Keywords: Lentil; Digital phenotyping; Morphological characterization

RESUMEN

El objetivo de este trabajo fue evaluar 81 cultivares de lenteja usando caracteres morfológicos y características de semilla utilizando fenotipado digital. El Calibre (C) y los caracteres Luminosidad (L), las coordenadas de color a y b, y el índice de color (IC) fueron medidos y analizados con un software apropiado; también fueron medidos el rendimiento (Y), altura de planta (PH) y los días a floración (DF). Se encontraron diferencias altamente significativas entre cultivares para todos los caracteres y se obtuvieron elevados valores de heredabilidad en sentido amplio (H2B) para las variables C (97%), IC (94%), a (93%) y L y b (83%) indicando la presencia de alta variabilidad genética. El fenotipado digital mostró ser una poderosa herramienta para la caracterización de germoplasma junto con la evaluación a campo de caracteres agronómicos. El Análisis de Componentes Principales y el análisis de agrupamiento permitieron la identificación de diferentes grupos de cultivares con características similares lo que conduce a un uso más eficiente del germoplasma disponible como cultivares comerciales o como parentales en un programa de mejoramiento genético. Entre estos grupos, el grupo 1 tuvo 32 cultivares con mayor C y el grupo 2 tuvo 21 cultivares con mayor Y.

Palabras clave: Lenteja; Fenotipado digital; Caracterización morfológica

INTRODUCTION

Lentil (Lens culinaris Medik. ssp. culinaris) is one of the most ancient crops in history (McVicar et al., 2005). This cool season pulse, used in human nutrition as whole grain or flour, is an excellent source of dietary fiber, protein, healthy fat, carbohydrates and a range of micronutrients (Thavarajah et al., 2011). Its high levels of low digestible carbohydrates reduces glycemic response in humans (Siva et al., 2017) and its high fiber content gives it strong satiating properties, resulting in lower food intake (Faris et al., 2013). This pulse is also a significant dietary source of a plethora of vitamins including folate, thiamin (B1) and riboflavin (B2) and relatively high levels of Mg, P, Ca and S (16).

All these characteristics make lentil a fundamental dietary component in low-income population and developing countries, as it is a substitute to proteins from livestock and fisheries (7) and have beneficial effects on human health (9).

The main consumer countries are those from Asia, north of Africa, Western Europe and part of Latin America. There are several market classes based on consumer preference, seed size and color. According to seed size the classes can be extra small (29-32 g/1000 seeds), small (33-45 g/1000 seeds), medium (51-52 g/1000 seeds) and large (55-73 g/1000 seeds). According to seed coat color they can be classified in green, brown, gray and purple or black; with cotyledon colors ranging from yellow to red and green (8).

In Argentina, lentil is cultivated mostly in the central area (south of the province of Santa Fe and north of the province of Buenos Aires), where is an important rainfed crop during the winter season (2). The main problem for growers is the lack of available cultivars, as only two commercial varieties are used in the present.

To solve this inconvenient, a breeding program is being carried out in the National University of Rosario, with the objective of obtaining new cultivars with higher yield and suitability for the different export markets.

A first step in any breeding program is to evaluate the variability of the germplasm available in the working collection using traits with agronomical importance. The characterization of traits whit high heritability and the evaluation of traits with low heritability and highly influenced by the environment can determine the utilization of this germplasm (3, 4).

The aim of the present work was to evaluate the genetic variability of a lentil collection for agronomical traits and seed characteristics (size and color) for later selection of accessions for commercial use or as parents in the breeding program. Seed traits where evaluated using digital phenotyping, performed by non-destructive, automated and image-based technology that offers an objective and quantitative method for estimation of morphological parameters as color and size.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material and experimental design

Eighty one accessions of a working collection (table 1, page 4) were sowed in July of 2016, in plots of 3 m long and 3 rows 0.25 apart (approximately 200 plants) at the Experimental Field of the College of Agricultural Sciences, Rosario National University, located in Zavalla (33°1' S and 60°53' W) in a complete randomized design with three replications.

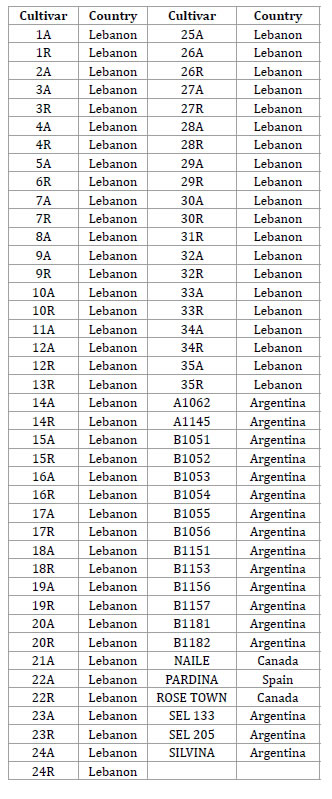

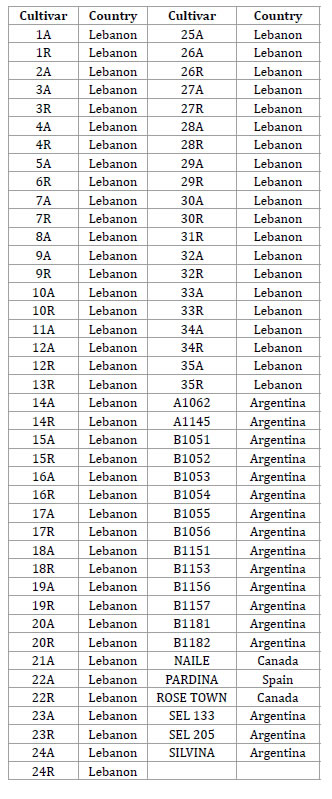

Table 1. Name and country of origin of the evaluated cultivars.

Tabla 1. Nombre y país de origen de los cultivares evaluados.

The harvest was done manually.

Traits analyzed

The analyzed variables were days to 50% of flowering (DF); plant height (PH), (cm from the root, in 20 plants per plot) and yield (Y grams per plot). Color traits and seed caliber (C) were measured on two-dimensional digital images of 600 dpi taken on a Samsung CLX 3300 scanner of samples of 50 seeds per repetition and analyzed using Tomato Analyzer (TA) software (12).

The color traits were the coordinates a and b, and the psychometric index of lightness L from the CieLab system of color where:

• Coordinate a indicates the greenness-redness of the color (-a is green, +a is red) and varies between -128 and 128.

• Coordinate b indicates blueness-yellowness of the color (-b is blue, +b is yellow) and varies between -128 and 128.

• Parameter L is an approximate measurement of luminosity, the property according to which each color can be considered as equivalent to a member of the greyscale between black and white.

With these color parameters, a color index (CI) was calculated as: CI = (1.000 x a) / (L x b).

Statistical analysis

An ANOVA between cultivars and a comparison of means using the Fisher's least significant difference test (LSD) (14) were performed.

Broad sense heritability was calculated as

H2B = σ2g/(σ2g+σ2e)

where:

σ2g = represents genotypic variance

σ2e = represents the environmental variance.

Finally, a Principal Component analysis (PC) and a Cluster analysis using average linkage method with Euclidean distances were performed in order to identify groups of cultivars with similar characteristics.

All statistical analysis were made using the software InfoStat for Windows (1).

RESULTS AND DISCUSION

Genetic variability

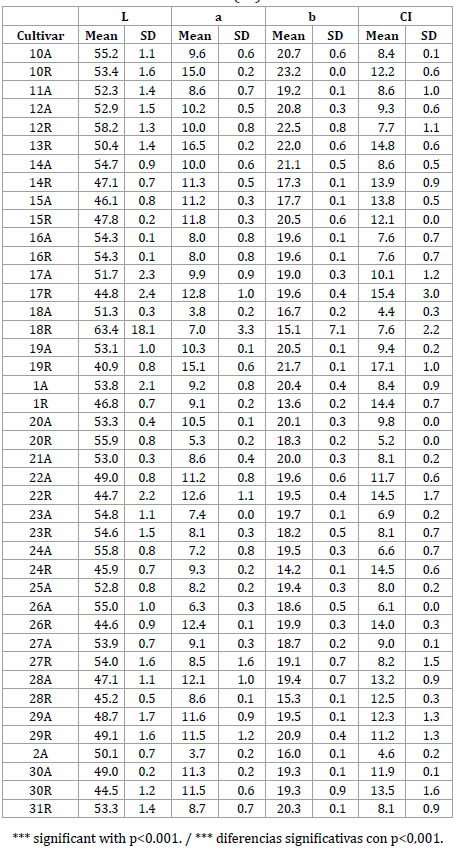

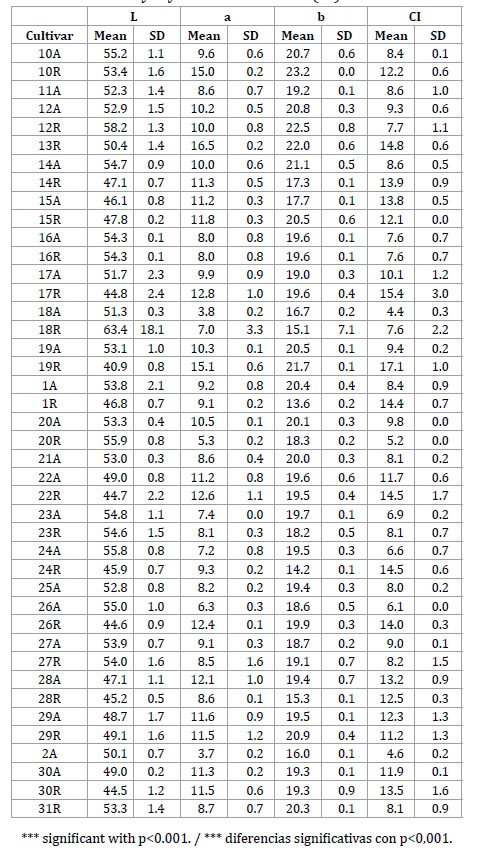

Mean value, standard deviation (SD), F value for the ANOVA analysis, Fisher’s least significant difference value (LSD) and broad sense heritability (H2B) for all the traits are shown in table 2, page 5-6; table 3, page 7-8.

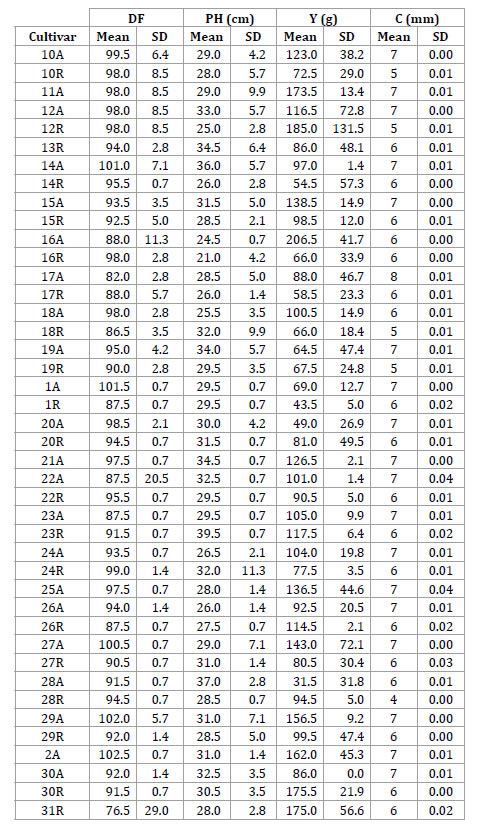

Table 2. Mean, standard deviation (SD), LSD value, F value and broad sense heritability (H2B) for days to flowering (DF), plant height (PH), yield (Y) and seed caliber (C).

Tabla 2. Media, desviación estándar (SD), valor de LSD, valor de F y Heredabilidad en sentido amplio (H2B) para los caracteres días a floración (DF), altura de planta (PH), rendimiento (Y) y calibre de grano (C).

Table 2 (cont.). Mean, standard deviation (SD), LSD value, F value and broad sense heritability (H2B) for days to flowering (DF), plant height (PH), yield (Y) and seed caliber (C).

Tabla 2 (cont.). Media, desviación estándar (SD), valor de LSD, valor de F y Heredabilidad en sentido amplio (H2B) para los caracteres días a floración (DF), altura de planta (PH), rendimiento (Y) y calibre de grano (C).

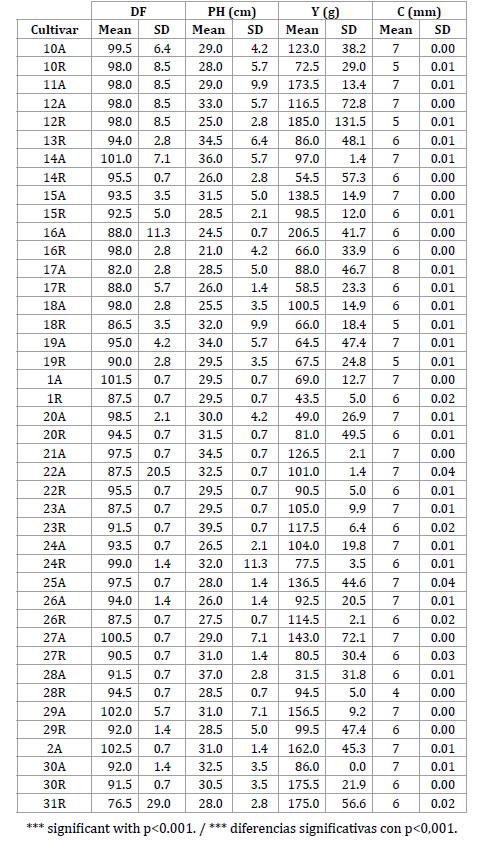

Table 3. Mean, standard deviation (SD), LSD value, F value and broad sense heritability (H2B) for L, a and b coordinates of color and color index (CI).

Tabla 3. Media, desviación estándar (SD), valor de LSD, valor de F y Heredabilidad en sentido amplio (H2B) para los caracteres L, las coordenadas de color a y b y el índice de color (CI).

Table 3. (cont.). Mean, standard deviation (SD), LSD value, F value and broad sense heritability (H2B) for L, a and b coordinates of color and color index (CI).

Tabla 3. (cont.). Media, desviación estándar (SD), valor de LSD, valor de F y Heredabilidad en sentido amplio (H2B) para los caracteres L, las coordenadas de color a y b y el índice de color (CI).

All traits presented highly significant differences between cultivars (p<0.001), and broad sense heritability varied between 0.33 for DF to 0.97 for C, demonstrating the existence of genetic variability suitable for selection purposes. Bermejo et al. (2012) in the evaluation of 28 lentil RIL's; Lázaro et al. (2001) in a working collection of Spanish materials and Erskine et al. (1998) in collections from ICARDA (International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas) found similar values of H2B.

Regarding mean values, for DF, cultivars 7A, Rose Town and Pardina were late (104 and 105 DF) while cultivar 34A was the earliest (57 DF).

In PH, cultivar 4A was the tallest (44 cm) while B1053 was the shortest, with only 20.5 cm of plant height. Cultivars B1157 and B1051 had the best yielding with 363 g plot-1and 317 g plot-1 respectively, and cultivar SEL was the poorest with 15.5 g plot-1.

Digital phenotyping showed that cultivars 17A, 22A, 19A and 30A had larger seeds with calibers of 7.5 mm, 7.4 mm, 7.4 mm and 7.3 mm respectively, while B1181, B1182 and 28R had the smallest seeds, with calibers ranging from 0.44 to 0.45. Color parameter L was high for cultivar 18R (63.43) and low for B1182 (36.40).

The a coordinate of color showed the highest values for 13R and 19R (16.45 and 15.10 respectively) meaning that these two cultivars are material for greater reddish color, while 35A, 18A and 2A showed the least (4.81, 3.79 and 3.70 respectively).

The b coordinate denotes the greenish color and was high for 10R and 12R, (23.22 and 22.45 respectively) and low for Pardina (13.26). When the color index (CI) was analyzed, cultivars B1182 (24.11) and B1181 (23.53) had the highest values, while 18A (4.43) was the lowest.

Cluster Analysis

Cluster analysis (figure 1, page 10), showed that cultivars conformed six groups with differential traits.

Figure 1. Cluster Analysis.

Figura 1. Análisis de conglomerados.

This analysis allows the identification of cultivars with convenient characteristics, as seed size. A comparison of mean values of each group (table 4, page 11) using the Fisher's least significant difference test (LSD) showed that Group 1 had 32 cultivars with high C; group 2 had 21 cultivars with higher Y but lower CI.

Table 4. Fisher's least significant difference test between group's means in the Cluster Analysis.

Tabla 4. Prueba de la mínima diferencia significativa de Fisher entre las medias de los grupos del Análisis de conglomerados.

Group 3 had 17 cultivars with high values for coordinates a and b; group 4 included only one cultivar (18R) with the highest L; group 5 had 4 cultivars with lower C and coordinate b; and group 6, with 6 cultivars, had the cultivars with higher DF and CI but lower C and L.

Principal Component Analysis

Principal component analysis showed that two principal components explained 58% of the variation in the data set (PC1, 40% and PC2, 18%) and with the addition of a third component the proportion of variation explained reached 73% (PC3, 15%).

However, when the first two components are plotted against each other (figure 2, page 11) the cultivars conform 4 clearly differentiated groups.

Figure 2. Biplot of the first two Principal Components.

Figura 2. Biplot de las dos primeras Componentes Principales.

PC1 was associated with C, L, a, b and CI while PC2 was associated with DF, PH and Y.

In figure 2 (page 11), points represent lentil cultivars and vectors represent analyzed traits.

The perpendicular projection of the points on the vectors indicates the relative position of that cultivar against the others for that particular trait, having the highest values those cultivars in the positive direction of the vector, while the angle between vectors shows the correlation among traits. In this case, cultivars B1181 and B1182 had the highest values of CI and cultivar B1051 had the highest yield. Correlations shows that traits CI and a, DF and PH, C and L, and Y and b have positive correlations, while CI and a have a negative correlation with L.

There is a clear concordance between groups obtained by Cluster Analysis and by Principal Component Analysis. Groups 2 and 6 are separated groups, and were conformed with the same cultivars in both analyses. Groups 1 and 2 in one hand, and groups 3 and 5 on the other, conform two different groups in the Principal Component analysis. The selected materials, as parents for a breeding program, were those from group 2, given their higher yields and shorter cycle, and those from group 1, with higher caliber.

CONCLUSIONS

Digital phenotyping showed to be a powerful tool for germplasm characterization along with field evaluation of agronomical traits. Principal Component Analysis and Cluster Analysis the identification of differentiated groups of cultivars with similar characteristics, leading to a more efficient use of the germplasm available.

Preliminary evaluation of the set of cultivars presented in this study demonstrate the existence of high phenotypic and genotypic diversity for different traits, showing their potential commercial or breeding value.

1. Balzarini, M.; Di Renzo, A.; González, L.; Tablada, M.; Guzmán; W. R. 2012. InfoStat software estadístico InfoStat versión 2008. Manual de usuario. Grupo InfoStat. FCA. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina.

2. Barreiro, E. 2010. Cadenas Alimentarias: Producción de lentejas [en línea] Edición No. 49. Argentina: Alimentos Argentinos. [Consultado: 13/09/2013]. Available in: <http:// www.alimentosargentinos.gov.ar/contenido/revista/ediciones/49/productos/ r49_10_Lentejas.pdf>.

3. Bermejo, C.; López Anido, F. S.; Cointry, E. L. 2012. Descripción de líneas recombinantes de lenteja (RIL) mediante caracteres morfológicos. Horticultura Argentina. 31: 74.

4. Carloni, E.; López Colomba, E.; Ribotta, A.; Quiroga, M.; Tommasino, E.; Griffa, S.; Grunberg, K. 2018. Analysis of genetic variability in vitro regenerated buffelgrass plants through ISSR molecular markers. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 50(2): 1-13.

5. Erskine, W.; Chandra, S.; Chaudhry, M.; Malik, I. A.; Sarker, A.; Sharma, B.; Tufail, M.; Tyagi, M. C. 1998. Abottleneck in lentil: widening its genetic base in South Asia. Euphytica. 101: 207-211.

6. Faris, M.; Takruri, H. R.; Issa, A. Y. 2013. Role of lentils (Lens culinaris L.) in human health and nutrition: a review Mediterr J Nutr Metab. 6: 3-16 DOI 10.1007/s12349-012-0109-8.

7. Financiera Rural. Monografía de la Lenteja. 2010. [en línea]. Dirección Ejecutiva de Análisis Sectorial. México. [Consultado: 07/05/2013]. Available in: <http:// www.financierarural.gob.mx/informacionsectorrural/Documents/Monografias/ Monograf%C3%ADa%20Lenteja_Mayo-2010.pdf>.

8. Government of Saskatchewan. 2016. Varieties of Grain Crops. Available in: http://www. saskseed.ca/images/varieties2016.pdf Accessed 26.06.2017.

9. Jenkins, D. J.; Kendall, W.; Augustin, L. S.; Mitchell, S.; Sahye-Pudaruth, S.; Blanco, M. S.; Chiavaroli, L.; Mirrahimi, A.; Ireland, C.; Bashyam, B.; Vidgen, E.; de Souza, R. J.; Sievenpiper, J. L.; Coveney, J.; Leiter, L. A.; Josse, R. G. 2012. Effect of legumes as part of a low glycemic index diet on glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Archives of Internal Medicine. 172(21): 1663-1660.

10. Lázaro, A.; Ruiz, M.; De la Rosa, L. & Martin, I. 2001. Relationship between agro/morphological characters and climatic parameters in Spanish landraces of lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.). Genetics Resources and Crop Evolution 48: 239-249.

11. McVicar, R.; Pearse, P.; Brenzil, C.; Hartley, S.; Panchuk, K.; Mooleki, P. 2005. Lentil in Saskatchewan. Saskatchewan Agriculture and Food. A. Vandenberg, S. Banniza, University of Saskatchewan. [(accessed August 2017)]. Available online: http:// publications.gov.sk.ca/documents/20/86381-Lentils in Saskatchewan.pdf.

12. Rodríguez, G.; Moyseenko, J.; Robbins, M.; Huarachi Morejón, N.; Francis, D.; Van der Knaap , E. 2010. Tomato Analyzer: A useful software application to collect accurate and detailed morphological and colorimetric data from two-dimensional objects. Journal of Visualized Experiment. 37: 1856.

13. Siva, N.; Thavarajah, D.; Johnson, C.; Duckett, S.; Jesch, E.; Thavarajah, P. 2017. Can lentil (Lens culinaris Medikus) reduce the risk of obesity? Journal of Functional Foods. Available in: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2017.02.01. Accessed August 2017).

14. Steel, R.; Torrie, J. 1993. Comparaciones múltiples. En Bioestadística. Principios y Procedimientos. McGraw and Hill. Eds. Segunda Edición. 622 p.

15. Thavarajah, D.; Thavarajah, P.; Sarker, A.; Materne, M.; Vandemark, G.; Shrestha, R.; Idrissi, O.; Hacikamiloglu, O.; Bucak, B.; Vandenberg, A. 2011. A global survey of effects of genotype and environment on selenium concentration in lentils (Lens culinaris L.): implications for nutritional fortification strategies. Food Chem. 125: 72-76.

16. United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). 2011. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference. Release 23. Retrievable from http://www.ars.usda.gov/research/ publications/ publications.htm? seq_no_115=243584 (accessed Jan 2011).