Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 55(2). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2023.

Original article

Effect

of cutting height, a bacterial inoculant and a fibrolytic enzyme on corn (Zea

mays L.) silage quality

Altura

de corte y adición de un inoculante bacteriano y una enzima fibrolítica sobre

la calidad del ensilado de maíz (Zea mays L.)

José A. Rueda 2

Carlos Iván

Medel Contreras 2

Jorge Hernández

Bautista 3

Agustín Corral

Luna 1

Monserrath Félix

Portillo 1

1

Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua. Facultad de Zootecnia y Ecología. Periférico

Francisco R. Almada km 1. Chihuahua. Chihuahua. 33820. México.

2

Universidad del Papaloapan. Instituto de Agroingeniería. Av. Ferrocarril SN.

Loma Bonita. Oaxaca. 68400. México.

3

Universidad Autónoma Benito Juárez de Oaxaca. Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria

y Zootecnia. Oaxaca. 68110. México.

*mvzsramirez@gmail.com

Abstract

This study aimed

to evaluate cutting height (CH) effects on ensiled corn without additives (C),

with a lactic acid bacteria inoculant (L), a fibrolytic enzyme (F), or a

mixture of both (FL), considering chemical composition and both in vitro digestibility

dry matter (IVDMD) and in vitro neutral detergent fiber (IVNDFD). Corn

was harvested at three different cutting heights (12, 25 or 42 cm above the

soil) and ensiled with or without additives (AD). Data

was analyzed according to a factorial design, with a 3 x 4 arrangement of

treatments and three repeats. Dry matter content was highest in C12 and lowest

in F12 (P<0.05) silages. As cutting height was higher, cell wall

content was lower (P<0.05). Even considering it increased after the

use of additives (P<0.05), the highest values occurred with FL

silages. Crude protein was equal (P˃0.05) between CH and increased (P<0.05)

with AD. The highest IVDMD was observed for 42 cm CH, while IVDMD and IVNDFD

were higher in C and F, but lower with FL. None of the inoculation treatments,

alone or combined improved corn silage quality. In fact, FL combination

decreased such quality.

Keywords: additives,

starch, biomass, soluble carbohydrates, NDFD, digestibility, fiber

Resumen

El objetivo de

este estudio fue evaluar el efecto de la altura de corte (AC) sobre la

composición química y la digestibilidad in vitro tanto de la materia

seca (DIVMS) como de la fibra detergente neutro (DIVFDN) de plantas de maíz

ensiladas sin (C), con inoculante de bacterias ácidos lácticas (L), una enzima

fibrolítica (F), o una mezcla de ambos (FL). El maíz fue cosechado a tres

alturas de corte (12, 25 y 42 cm por encima de suelo) y ensilado con o sin

aditivos (AD). Los datos se analizaron de acuerdo con un diseño con arreglo

factorial 3 x 4 con tres repeticiones. El contenido de materia seca en los

ensilados fue más alto en C12 y más bajo en F12 (P<0,05). A mayor

altura de corte, la fracción de la pared celular fue menor (P<0,05),

aunque con el uso de aditivos, esta aumentó (P<0,05); los valores más

altos ocurrieron con FL. La proteína cruda fue igual (P˃0,05) entre AC y

se incrementó (P<0,05) con AD. La DIVMS más alta se observó en la

altura de 42 cm AC, mientras que la DIVMS y DIVFDN fueron más altas con C y F y

más bajas con FL. Ningún aditivo, solo o en combinación, mejoró la calidad del

ensilado de maíz; de hecho, la combinación FL disminuyó dicha calidad.

Palabras clave: aditivos,

almidón, biomasa, carbohidratos solubles, DFDN, digestibilidad, fibra

Originales: Recepción: 25/11/2021 - Aceptación: 31/07/2023

Introduction

Feeding corn

silage to dairy cows is a growing practice in the Mexican tropics. Maximizing

nutrient bioavailability of corn silage would represent important economic and

productive advantages. Specifically, enhancing cell wall degradability might

improve profits while reducing both solid excretion and methane production, and

potentially reducing grain level in feed up to 3% (40).

Plant cell walls

are a major source of energy for ruminants. However, only less than 50% are readily

digested and utilized by the ruminant host (3).

In fact, the low degradability of cell wall fractions (cellulose,

hemicellulose, pectin and lignin) is a key factor limiting its use by rumen

microorganisms. In addition to corn variety, crop maturity, kernel processing

and particle cut length (12), another

alternative to improve fiber degradability of corn silage is to increase

cutting height at harvest (9) improving

both forage quality and milk production (9, 12, 21).

Lactic acid

bacteria (LAB) inoculants and exogenous fibrolytic enzymes (EFE) have become

popular as silage additives intended to improve silage nutritional value (5, 17, 26). LAB improve fermentation

characteristics by promoting faster pH decline, avoiding both proteolysis and

excessive fermentation of water-soluble carbohydrates (WSC) (25). In addition, LAB also improve the lactic

acid-acetic acid ratio and promote low ammonia nitrogen content (38). Furthermore, dry matter loss is reduced by

35%, while intake, digestibility, weight gain, and milk production are also

improved (38). Exogenous fibrolytic

enzymes promote cellulose and hemicellulose hydrolysis, therefore improving

cell wall degradation while releasing WSC, which undergoes subsequent

fermentation by LAB (15, 33).

Additionally, the enzymatic additives improve fermentation by stimulating the

production of acids and lowering pH and ammonia nitrogen in the silage (38). When EFE are added to forage, parameters

like digestibility, dry matter intake and milk production, usually increase (38). However, data on how EFE affects

digestibility of DM and NDF have been mostly inconsistent (17, 38).

Among other

factors, LAB efficacy depends on WSC content of the forage to be ensiled, while

EFE extent of action is related to both NDF content and chemical composition.

It is hypothesized that changing the grain-to-stover ratio through cutting

height might promote the synergistic effect between LAB and EFE on silage

digestibility. This study aimed to assess the single and combined effects of

LAB and/or EFE on chemical composition and in vitro digestibility of the

DM and NDF in corn silage when corn is harvested at different cutting heights.

Materials

and methods

Corn was planted

in Jose Azueta, Veracruz, Mexico; at 18°05’50” N and 95°39’35’’ W, and 16 m

above sea level. Local climate is warm and subhumid with summer rains (Aw1).

Maximum, mean and minimum temperatures are 31.8, 26.3 and 20.8°C, with an

annual rainfall of 1601 mm (16). The most

common soil types are gleysol (39%) and phaeozem (39%).

Hybrid corn

DK-357 (DEKALB®) was established on November 29 of 2017, and grown under

rainfed conditions. Sowing density was 75,000 seeds ha-1, at 80 cm

between rows. Fertilization consisted of 175 kg ha-1 of diammonium phosphate

(DAP, 18-46-00) during sowing.

Treatments

and silages

Corn was

harvested when dry matter content approached 35%, around day 103 after

planting. On the plot, ten out of 108 rows were randomly selected and three 10

m long sections were sampled at 20, 150 and 280 m from the end row. On every

sampling, plant number and height, stem diameter and node number were recorded.

Then, six random plants were cut at 12, 25 or 42 cm cutting heights (CH). A

total of 60 plants were harvested for every CH. Plants were then transported to

the Laboratory of the Universidad del Papaloapan, in Loma Bonita, Oaxaca.

Fifty-five out

of the 60 plants, were assigned to four treatments: without additive (C,

control) and with additives (AD) Fibrozyme® (F), Sil-All® (L), and with

Fibrozyme plus Sil-All (FL). According to manufacturers, Fibrozyme® (Alltech

Inc., Nicholasville, KY, USA) is a fermentation extract of Aspergillus niger

and Trichoderma viride with 31.0 and 43.4 IU of xylanase and

cellulase activity, respectively (11). Sil-All® (Lallemand Specialties, Inc.

Milwaukee, WI, USA) contains Lactobacillus plantarum, Pediococcus

acidilactici, Enterococcus faecium, Lactobacillus salivarius at a minimum

ratio of 2.1 x 1010 CFU g-1.

Plants were cut

with a stationary gas chopper (Raiken® RKP-3000B) before filling three

laboratory silos with their corresponding treatment (C12, C25, C42, F12, F25,

F42, L12, L25, L42 or FL12, FL25, FL42). Laboratory silos with a capacity of

3.0 kg of fresh forage, were made from PVC tubes (15.7” high x 4” wide).

Sil-All dosage was provided according to manufacturer’s specifications (10 mg

kg-1 of fresh forage). Fibrozyme dosage was 60 mg kg-1 of

the DM to be ensiled. Twenty-two milliliters of distilled water dissolved each

additive, and then the solution was spread over the chopped forage. Treatment C

consisted of 22 mL of distilled water spread over the forage. Then, laboratory

silos were filled up and compacted manually, covered with a grow bag and sealed

with brown tape. The 36 laboratory silos were weighted and kept at room

temperature in the Laboratory of the Universidad del Papaloapan for 50 days.

Chemical

analysis

After 50 d of

ensiling, all laboratory silos were weighted and then opened. Considering each

silo, pH was assessed in a 25 g sample mixed in 250 mL of distilled water and

blended for 30 s at maximum speed. The solution was filtered through two

cheesecloth layers before taking the pH readings with a HANNA® potentiometer

(model pH 209, Instruments Inc. USA).

Partial dry

matter content was determined with 500 g samples from each silo, oven dried at

60°C for 48 h and ground through a Wiley® mill to pass a 1 mm screen (10). Ground samples were used to estimate total

dry matter (method # 930.15), ash (method # 942.05) and crude protein content

(CP, method # 990.03), according to AOAC (2006).

Furthermore, cell wall fractions of neutral detergent fiber (NDF), acid

detergent fiber (ADF), and acid detergent lignin (ADL) were determined. The NDF

analysis was carried out using Na2SO3 and α-amylase. ADL

analysis was run in a beaker by immersion in 72% H2SO4.

Cell-wall fractions content was determined sequentially in the ANKOM200® fiber

analyzer, using Ankom F57® filter bags, following the procedures proposed by

the company. Additionally, non-fibrous carbohydrates (NFC) content was

calculated using the equation: NFC (%) = 100 – [NDF% + CP% + ether extract % +

ash], where NDF was not corrected for CP or ash, and ether extract was

considered 3.2% for all silages (28).

In

vitro digestibility

of DM and NDF

In vitro DM digestibility

(IVDMD) and NDF (IVNDFD) were determined by incubating silage samples in Ankom

F57® filter bags for 48 h in a DAYSI-II® incubator, as recommended by the

manufacturer. Ruminal inoculum was collected from three slaughtered cows in the

Loma Bonita slaughterhouse. Donors grazed tropical pastures.

Total digestible

nutrients per hectare (TDN ha-1) was calculated through the equation: %TDN =

87.84 - (0.70 x ADF) (36) and multiplying

those values in silages by dry matter yield (DMY) obtained at each cutting

height.

Statistical

analyses

Data were

analyzed for effects of AD, CH and CH x AD using a general linear model (31) as a completely randomized design in a 4 x 3

factorial arrangement with three repeats per treatment: one control (C), three

treatments including additive and/or enzyme (F, L and FL) and three CH (12, 25

and 42 cm). Mean comparison was run by least significant difference (LSD), at P≤0.05.

Additionally, cell wall fractions and forage yield in response to CH were

analyzed by regression analysis.

Results

and discussion

Dry

matter content

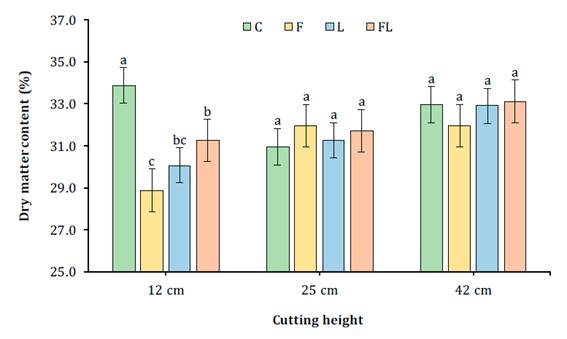

Significant

differences in DM content of corn silage were found for the interaction CH x AD

(P=0.01). At 12 cm cutting height, C12 (control treatment) showed the

highest (P<0.05) and F12 showed the lowest (P<0.05) DM

content, with 33.9, 31.2, 30.1 and 28.9% for C12, FL12, L12 and F12,

respectively, while for 25 and 42 cm cutting heights, no differences were found

(figure 1).

For each cutting height bars with different letter

are statistically different (P<0.05). C - control (distilled water

only); F - Fibrozyme® (fibrolytic enzymes with xylanase activity); L - Sil-All®

(bacterial inoculant for silage based on lactic acid bacteria); FL - mixture of

Fibrozyme + Sil-All.

Para cada altura de corte barras con diferente letra

son estadísticamente diferentes (P<0,05). C- control (solo agua

destilada); F - Fibrozyme® (enzimas fibrolíticas con actividad xilanasa); L -

Sil-All® (inoculante bacteriano para ensilaje a base de bacterias

ácido-lácticas); FL - mezcla de Fibrozyme + Sil-All.

Figure 1. Dry

matter (%) of corn silage in response to additive (C, F, L, FL) and cutting

height (12, 25, 42 cm).

Figura 1. Materia

seca (%) de ensilados de maíz en respuesta al aditivo (C, F, L, FL) y a la

altura de corte (12, 25, 42 cm).

Harvesting at

higher CH implied an improvement of digestible nutrients per kilogram of DM,

then reflected in milk yield, both per area and weight unit. These improvements

justify leaving the most fibrous and lignified part of the stem on the field.

On the other hand, an increase of 1.7 units (5.2%) in DM content is expected

with the increase in CH from 12 to 42 cm, due to higher DM content in cobs

compared to leaves or stems (23). In this

regard, higher CH results in increased DM content in corn crops for ensiling,

explained by a higher stover-to-grain ratio in the ensiled mass (18). Regarding AD, Colombatto

et al. (2004) found no effect of added EFE on corn silage DM, with

33.3 and 33.8% average fresh and ensiled corn, respectively.

Dry

matter yield (DMY) due to cutting height effect

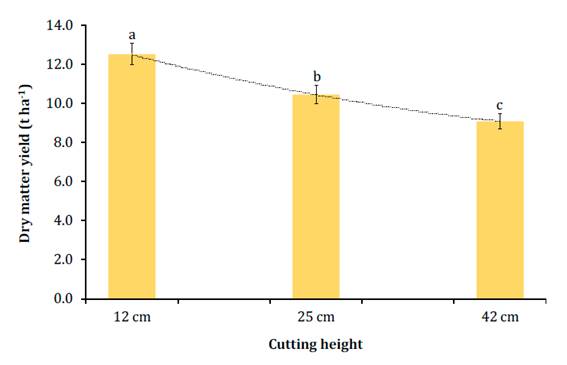

Average DMY was

10.7 t ha-1. At conventional CH (12 cm) DMY was low (12.5 t ha-1),

given three factors: final plant density (52,430 plants ha-1), plant height

(198.3 cm) and rainfall, considering water availability is a determining factor

in forage yield (30). As expected, DMY

was highest (P<0.0001) for the 12 cm as compared to 25 cm and 42 cm

CH (figure 2).

Figure 2. Dry

matter yield (t ha-1) of the whole corn plant harvested at three cutting

heights (CH).

Figura 2. Rendimiento

de materia seca (t ha-1) de la planta entera de maíz cosechada a tres alturas

de corte.

DMY decreases as

CH increases, because of the lower proportion of stem in plants harvested at a

greater height. On the other hand, DMY is also affected by DM content of the

harvested forage, which might vary among different CH (figure 1,

page 132). Both forage DM and forage moisture content, are also related to the

amount of stem left on the field at each CH. That is, the higher the CH at

harvest (such as 25 cm and 42 cm) the lower the amount of moisture carried

within the plant, which in the end is reflected in a higher DM content, since

the stem contributes the most to plant moisture (21,

40).

DMY is inversely

proportional to cutting height. In this study, the greater reduction in DMY

occurred between 12 and 25 cm (20.1%) CH; followed by 25 to 42 cm (15.1%);

while for CH 12 to 42 cm, DMY was considerably higher (37.3%). The regression

analysis showed that for every 1 cm increase in CH above 12 cm, DMY decreases

112 kg ha-1 (R2=0.51; P<0.05). The 37.3% decrease in DMY from 12

to 42 cm is significantly high compared to results published by other research

groups. For instance, Wu and Roth (2005) reported a

7.4% reduction in DMY when the CH changed from 17 to 48 cm; Kung et al. (2008) found a DMY drop of 20.1% from

10-15 to 46-51 cm, and Neylon and Kung (2003)

reported decreases of 5 to 10% DMY when CH went from 12.7 to 45.7 cm. These

reported DMY dissimilarities might be explained by the differences in plant

heights among them. For example, Kung et al. (2008)

reported an average plant height of 3.04 m, while in the present study, average

was 1.98 m. Plant height must be considered before deciding on harvest cutting

height.

Chemical

composition

pH ranged from

3.86 to 4.43, with an average pH of 4.0, suggesting all silages were well preserved.

Silage pH was not affected by the added fibrolytic enzyme, bacterial inoculant or

cutting height. The purpose of adding an inoculant or enzyme was to improve

forage fermentation by stimulating organic acids production and thus lowering

pH (36). However, the addition of L, F or

their combination did not stimulate fermentation of WSC due to EFE effect,

since final pH remained unaffected, as in previous studies (6, 8).

The activity of

most EFE improves when pH is above 4.5 (2, 38).

It has been suggested that EFE work better at a ruminal pH close to neutrality

(8). Neylon and Kung (2003), did not find

pH changes between corn cutting heights at 12.7 or 45.7 cm, at 34% of DM.

Usually, when adding an inoculant, studies focus both on pH and acid concentration

(9, 24); given the speed at which pH

falls and stops enzymatic and bacterial activity plays a key role in avoiding

unnecessary nutrient loss. However, in this work pH was not measured at

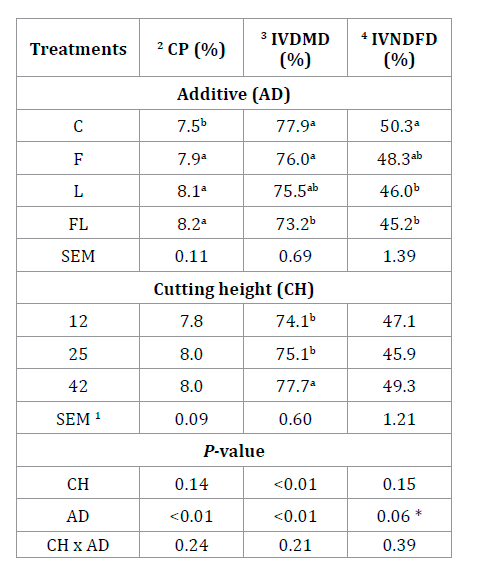

different times. Crude protein (CP) in silages was higher (P<0.01)

with L, F or the combination LF, as compared to the control (table

1), registering an increase of 0.4 to 0.8 %.

Table

1. Crude protein (CP, % of DM) and in

vitro digestibility of corn silages harvested at three cutting heights (in

cm) and inoculated with lactic acid bacteria and exogenous fibrolytic enzymes.

Tabla 1.

Proteína cruda (PC, % de la MS) y digestibilidad in vitro de ensilados

de maíz cosechados a tres alturas de corte (en cm) e inoculados con bacterias

ácido lácticas y enzimas fibrolíticas exógenas.

ab

For each factor, different letters indicate statistical differences (P≤0.05).

1 SEM - Standard error mean; 2 CP - crude protein; 3

IVDMD - in vitro dry matter digestibility, after 48 h of incubation in

the DaisyII equipment; 4 IVNDFD - in vitro neutral detergent

fiber digestibility, after 48 h of incubation in the DaisyII equipment; C -

control (distilled water); F - Fibrozyme® (fibrolytic enzymes with xylanase

activity); L - Sil-All® (bacterial inoculant for silage based on lactic acid

bacteria); FL - mixture of Fibrozyme + Sil-All. * - a trend.

ab

Para cada factor, diferentes letras indican diferencia estadística (P≤0.05);

1 SEM - Error estándar de la media; 2 CP - proteína

cruda; 3 IVDMD - digestibilidad in vitro de la materia seca,

después de 48 h de incubación en el equipo DaisyII; 4 IVNDFD -

digestibilidad in vitro de la fibra detergente neutro, después de 48 h

de incubación en el equipo DaisyII; C - control (solo agua destilada); F -

Fibrozyme® (enzimas fibrolíticas con actividad xilanasa); L - Sil-All®

(inoculante bacteriano para ensilado a base de bacterias ácido lácticas); FL -

mezcla de Fibrozyme + Sil-All. * - una tendencia.

Thus, as

previously documented, we assume less proteolysis when these additives are used

(14, 35). Bacterial inoculants promote

faster pH decline in silage with the consequent prevention of more WSC

consumption, as well as further proteolysis.

The lower CP

content recorded in the control (C) may be related to higher (P<0.05)

DM content (32.6, 30.9, 31.4 and 32%) and less DM loss (P<0.05)

during fermentation in these silages (0.97, 2.97, 1.85 and 1.87% for C, F, L,

and FL, respectively), causing CP dilution. This is also supported by the fact

that the treated silage showed lower quality, evidenced by a higher fiber

content and a lower digestibility than C silages. Besides, it has been widely

stated that protein content in corn silages is not affected by CH at harvest (19, 22, 38). Finally, average CP content was

7.9%, within the expected range according to NRC (2001).

Cell-wall

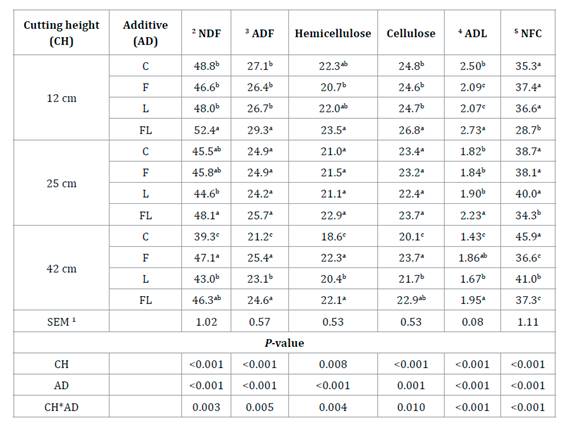

fractions. The

NDF, ADF, hemicellulose, cellulose and ADL, as well as non-fiber carbohydrates

(NFC), showed interaction effects (P<0.01). The lower cell wall and

higher NFC content occurred in C42 silage (table 2).

Table

2. Cell wall fractions (% of DM) in corn

silages harvested at three cutting heights and inoculated with lactic acid

bacteria and exogenous fibrolytic enzymes.

Tabla 2.

Fracciones de la pared celular (% de la MS) de ensilados de maíz cosechados a

tres alturas de corte e inoculados con bacterias ácido lácticas y enzimas

fibrolíticas.

For each cutting height means with different letters

are statistically different (P≤0.05). SEM 1- Standard error

mean; 2 NDF - neutral detergent fiber; 3 ADF - acid

detergent fiber; 4 ADL - acid detergent lignin; 5 NFC - non-fiber

carbohydrates [100 - (NDF + CP + ether extract + ash)]; C - control (distilled

water); F - Fibrozyme® (fibrolytic enzymes with xylanase activity); L -

Sil-All® (bacterial inoculant for silage based on lactic acid bacteria); FL -

mixture of Fibrozyme + Sil-All.

Para cada altura de corte, medias con diferente

letra son estadísticamente diferentes (P≤0,05). 1 SEM - Error

estándar de la media; 2 NDF - fibra detergente neutro; 3

ADF - fibra detergente ácido; 4 ADL- lignina detergente ácido; 5 NFC

- carbohidratos no fibrosos [100- (PC + cenizas + grasa cruda + FDN)]; C -

control (solo agua destilada); F - Fibrozyme® (enzimas fibrolíticas con

actividad xilanasa); L - Sil-All® (inoculante bacteriano para ensilado a base

de bacterias ácido lácticas); FL - mezcla de Fibrozyme + Sil-All.

Conversely, the

highest cell wall and the lowest NFC contents converged in FL12 silage. In

fact, all FL silages showed higher cell walls and lower NFC contents as compared

to the remaining treatments (P<0.05). Higher fiber values in FL

silages could be consequence of a dilution effect due to a greater loss of WSC

occurring in this treatment (15, 17). At

the CH of 12 cm, hemicellulose and ADL content were lower for the F silages, as

compared to C silages, whereas, ADL values of the L silages (P<0.05)

were lower than those of the C silages. Cell wall content was affected by

cutting height (P<0.05) i.e., the higher cutting height had

the lower cell wall content. The latter remained true for the treatments

without additives (P=0.05) (table 2).

In this

research, both additives combined resulted in a setback regarding the expected

reduction in cell wall fractions. Noteworthy is that EFE activity depends on

several factors (type of enzyme, type of forage, pH, temperature, dosage, and

others), and if most of these conditions are met, greater enzymatic efficacy

may be achieved upon the potentially digestible fraction of the forages.

The NDF, ADF and

ADL contents were within the range stated by the NRC

(2001) for corn silages with 32 to 38% DM. However, our values were

slightly higher than those reported in previous studies (6, 22, 24, 40). Such discrepancies might be

explained by environmental differences as is widely known that grasses

accumulate more cell walls when grown in warmer climates, such as those from

intertropical regions (4), as might be

the case for the corn genotype herein considered.

In this study,

the use of fibrolytic enzyme negatively impacted silage fiber content and

digestibility, probably a consequence of the high xylanase activity presented

in the used EFE. It has been observed that enzymes with xylanase activity do

not improve DM or NDF biodegradability (11).

In contrast, an improvement in NDF degradation occured when EFE had higher

endoglucanase activity (11, 33). In this

regard, Wallace et al. (2001) reported that

several products with endoglucanase activity were more effective at stimulating

fermentation in corn silage than those with high xylanase activity and low

endoglucanase activity.

Finally, Vallejo et al. (2016) concluded that cellulases

were more effective than xylanases when added to corn straws. Unlike ferulic

acid esterase, xylanase and cellulase cannot hydrolyze the ester bonds between

sugars and hydroxycinnamic acids within the cell wall (2). On the other hand, according to the

manufacturer the Fibrozyme is recommended for TMR and not for ensiled forage.

In this regard, Singh et al. (2018) found

that xylanases and cellulases are more effective in TMR than applied on

concentrate or forage. Furthermore, LAB are more effective in grasses with

lower WSC and low buffering capacity than in forages like corn, sorghum or

sugar cane (29). Lastly, LAB do not have

a direct influence on forage DM digestibility, but they can promote better

silage fermentation.

In

vitro DM

and NDF digestibility

The IVDMD was

affected by both additives and cutting height, while IVNDFD showed a trend (P=0.06)

by additive effect (table 1, page 134). Both IVDMD and

IVNDFD, were higher in C and F and lower in FL silages (P<0.05). In

this study, IVDMD and IVNDFD followed a similar pattern as compared to cell

wall content (table 2, page 135). The highest digestibility

occurred for C silages, where fiber was lower, whereas the opposite occurred

for FL silages. Regarding cutting height, IVDMD was higher (P<0.05)

for 42 cm (77.7%). IVNDFD was unaltered by cutting height (P=0.15);

however, the 42 cm treatment exceeded that of 12 cm by 2.2% (table

1, page 134).

The highest and

lowest IVDMD observed in C and FL respectively, might be related to the lowest

(0.97%) and highest (2.97%) DM losses during fermentation. Consequently, less

degradable fibrous components increased, either by dilution or by the greater

degradation of WSC when additives are used. However, this last hypothesis is

weakly supported since pH was not lower. On the other hand, it is also possible

that LAB did not use WSC effectively. Sheperd and Kung

(1996) observed that after 56 d of fermentation, pH was equal (3.55) for

silage treated with EFE compared to untreated, where glucose content

represented 0.10 and 0.37% of DM (P<0.05), respectively; suggesting

that cell walls were partially hydrolyzed by added enzymes. On the other hand,

after 196 d of fermentation with and without EFE, pH was 3.63 and 3.56 (P<0.05)

and glucose percentages were 0.09 and 0.10%, respectively. Increases in IVDMD

by varying cutting height from 12 to 42 cm, accorded with many studies showing

that varying cutting height at harvest implies improvements (12, 27) in corn silage digestibility of about 2.5

and 4.7% for IVDMD and IVNDFD, respectively (40).

Corn silage

nutritional value could not be improved by EFE, LAB or their combination, since

IVDMD and IVNDFD at 48 h of incubation were lower than in the control

treatment. Previous studies reported similar effects of EFE on silage (19, 24, 32); while other studies documented that

EFE increased degradation rate after 12 and 24 h of in vitro incubation,

but not after 48 or 96 h (6). This is

supported by other studies (7), reporting

that EFE promote a fast degradation of some fraction of fiber, but have no

activity upon the less degradable fraction. Accordingly, digestion rate

increases within the first hours of incubation, then decreases until an

asymptote (20), given by lack of

substrate (6) or inability of enzymes

(whether exogenous or ruminal) to degrade that part of the fiber.

Adding EFE and

LAB to the forage before ensiling, reduced digestibility of corn silage,

particularly when used together. Stokes (1992) also

reported this antagonistic effect between EFE and LAB when they are combined.

Also, Lynch et al. (2015) reported that

adding EFE alone or in combination with ferulic acid inoculant, did not improve

corn silage fermentation or nutritional value, and even resulted in negative

effects on these parameters.

In this study,

neither EFE nor LAB alone, or their combination, showed a positive effect on

corn silage quality. These results coincide with other studies on EFE alone (13, 19), or combined with LAB (5, 24, 26). However, more research should confirm

these results. Gandra et al. (2017) concluded

that the combination of EFE and LAB had a minimal synergistic effect on guinea

grass silage quality when added to increase NDF digestibility and decrease

silage proteolysis.

In line with previous

reports (21), cutting height did not

affect IVNDFD (P=0.15) in this study. Nevertheless, most studies do

report differences in NDF digestibility. Wu and Roth

(2005) observed a 6.7% increase in IVNDFD from 17 to 49 cm cutting heights,

while Neylon and Kung Jr (2003) found that

digestibility went from 48.7 to 51.5% from 12.7 to 45.7 cm cutting heights. The

latter result was attributed to a lower NDF content in silage from corn cut at

taller heights. According to Lewis et al. (2004),

66.1, 67.3 or 69.1% of IVNDFD occurred from 15, 30 or 46 cm height,

respectively, in three corn hybrids harvested at 35% DM.

Total

digestible nutrients (TDN)

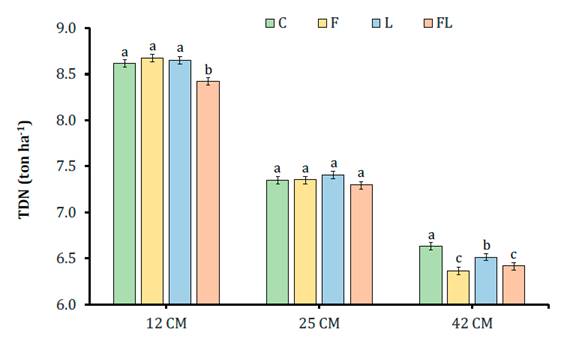

An interaction

CH x AD (P=0.008) occurred for TDN per hectare (TDN ha-1) (figure 3).

For each cutting height bars with different letters

are statistically different (P<0.05). C - control (distilled water

only); F - Fibrozyme® (fibrolytic enzymes with xylanase activity); L - Sil-All®

(bacterial inoculant for silage based on lactic acid bacteria); FL - mixture of

Fibrozyme + Sil-All.

Para cada altura de corte barras con diferente letra

son estadísticamente diferentes (P<0,05). C- control (solo agua

destilada); F - Fibrozyme® (enzimas fibrolíticas con actividad xilanasa); L -

Sil-All® (inoculante bacteriano para ensilaje a base de bacterias

ácido-lácticas); FL - mezcla de Fibrozyme + Sil-All.

Figure 3.

Total digestible nutrients (TDN) of corn silages treated with different

additives (C, F, L, FL) at three cutting heights (CH).

Figura 3.

Nutrientes digestibles totales (TND) de ensilados de maíz tratados con

diferentes aditivos (C, F, L, FL) a tres alturas de corte.

The treatment

FL12 showed the lowest TDN yield. At 25 cm, no differences were found between

treatments, while at 42 cm, TDN was higher in C and L, but lower in F and FL.

These data show that F negatively affected TDN ha-1. Moreover, cutting height

affected nutrients yield by area reducing 24.5% when cutting height changed

from 12 to 42 cm. This decrease is especially important in corn plants with

reduced height, as in this study.

Conclusions

Corn silage

quality was not affected by adding a bacterial inoculant or a fibrolytic

enzyme. The combination of both, inoculant and enzyme, decreased corn silage

quality by promoting greater content of cell wall fractions and decreasing dry

matter digestibility. Silage quality was greater for the 42 cm cutting height,

but this cutting height produced 37.3% less dry matter and 24.5% less nutrients

yield. The authors recommend focusing on good practices when ensiling.

1. AOAC

(Association of Official Agricultural Chemist). 2006. Official methods of

analysis. 18th ed. AOAC International, Arlington. VA.

2. Arriola, K.

G.; Kim, S. C.; Staples, C. R.; Adesogan, A. T. 2011. Effect of fibrolytic

enzyme application to low- and high-concentrate diets on the performance of lactating

dairy cattle. In Journal of Dairy Science. 94(2): 832-841. DOI:

10.3168/jds.2010-3424

3. Badhan, A.;

Jin, L.; Wang, Y.; Han, S.; Kowalczys, K.; Brown, D.; Juarez A. C.;

Latoszek-Green, M.; Miki, B.; Tsang, A.; McAllister, T. 2014. Expression of a

fungal ferulic acid esterase in alfalfa modifies cell wall digestibility. In

Biotechnology for Biofuels. 7(1): 39. DOI: 10.1186/1754-6834-7-39

4. Berone, G.;

Bertrám, N.; Di Nucci, E. 2021. Forage production and leaf proportion of lucerne

(Medicago sativa L.) in subtropical environments: fall dormancy, cutting

frequency and canopy effects. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias.

Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 53(1): 79-88. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.008

5. Bureenok, S.;

Langsoumechai, S.; Pitiwittayakul, N.; Yuangklang, C.; Vasupen, K.;

Saenmahayak, B.; Schonewille, J. T. 2019. Effects of fibrolytic enzymes and

lactic acid bacteria on fermentation quality and in vitro digestibility

of Napier grass silage. In Italian Journal of Animal Science. 18(1): 1438-1444.

DOI: 10.1080/1828051X.2019.1681910

6. Colombatto,

D.; Mould, F. L.; Bhat, M. K.; Phipps, R. H.; Owen, E. 2004. In vitro evaluation

of fibrolytic enzymes as additives for maize (Zea mays L.) silage II.

Effects on rate of acidification, fibre degradation during ensiling and rumen

fermentation. In Animal Feed Science and Technology. 111(1-4): 129-143. DOI:

10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2003.08.011

7. Colombatto,

D.; Mould, F. L.; Bhat, M. K.; Owen, E. 2007. Influence of exogenous fibrolytic

enzyme level and incubation pH on the in vitro ruminal fermentation of

alfalfa stems. InAnimal Feed Science and Technology . 137(1-2):

150-162. DOI: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2006.10.001

8. Dehghani, M.

R.; Weisbjerg, M. R.; Hvelplund, T.; Kristensen, N. B. 2012. Effect of enzyme

addition to forage at ensiling on silage chemical composition and NDF

degradation characteristics. In Livestock Science. 150 (1-3): 51-58. DOI:

10.1016/j.livsci.2012.07.031

9. Diepersloot,

E. C.; Heizen, C. Jr.; Saylor, B. A.; Ferraretto, L. F. 2022. Effect of cutting

height, microbial inoculation, and storage length on fermentation profile and

nutrient composition of wholeplant corn silage. In Translational Animal

Science. 6(2): 1-10. DOI: 10.1093/tas/ txac037

10. dos Santos, A.

P. M.; Santos, E. M.; Silva de Oliveira, J.; Pinto de Carvalho, G. G.; Garcia

Leal de Araújo, G.; Moura Zanine, A.; Martins Araújo Pinho, R.; Ferreira, D. de

J.; da Silva Macedo, A. J.; Pereira Alves, J. 2021. Effect of urea on gas and

effluent losses, microbial populations, aerobic stability and chemical

composition of corn (Zea mays L.) silage. Revista de la Facultad de

Ciencias Agrarias . Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 53(1):

309-319. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.030

11. Eun, J. S.;

Beauchemin; K. A.; Schulze, H. 2007. Use of exogenous fibrolytic enzymes to

enhance in vitro fermentation of alfalfa hay and corn silage. In Journal

of Dairy Science. 90(3): 1440-1451. DOI: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(07)71629-6

12. Ferraretto, L.

F.; Shaver, R. D.; Luck, B. D. 2018. Silage review: recent advances and future technologies

for whole-plant and fractionated corn silage harvesting. In Journal of Dairy Science.

101(5): 3937-3951. DOI: 10.3168/jds.2017-13728

13. Gallardo,

I.; Bárcena, R.; Pinos-Rodríguez, J. M.; Cobos, M.; Carreón, L.; Ortega, M. E.

2010. Influence of exogenous fibrolytic enzymes on in vitro and in

sacco degradation of forages for ruminants. InItalian Journal of Animal Science .

9(e8): 34-38. DOI: 10.4081/ijas.2010.e8

14. Gandra, J.

R.; De Oliveira, E. R.; De Goes, R. H. T. B.; De Oliveira, K. M. P.; Takiya, C.

S.; Del Valle, T. A.; Araki, H. M. C; Silveira, K.; Silva, D.; Da Silva Pause,

A. G. 2017. Microbial inoculant and an extract of Trichoderma

longibrachiatum with xylanase activity effect on chemical composition,

fermentative profile and aerobic stability of guinea grass (Pancium máximum Jacq.)

silage. In Journal of Animal and Feed Sciences. 26: 339-347. DOI:

10.22358/jafs/80776/2017

15. Getabalew,

M.; Mindaye, A.; Alemneh, T. 2022. Silage and enzyme additives as animal feed

and animals response. In Archives of Animal Husbandry & Dairy Science.

2(4): 1-6. DOI: 10.33552/AAHDS.2022.02.000543

16. INEGI

(Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). 2017. Anuario estadístico y

geográfico de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave 2017. INEGI, México. 1222 p.

http://ceieg.

veracruz.gob.mx/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2018/04/AEGEV-2017.pdf (fecha de

consulta: 21/08/2020).

17. Irawan, A.;

Sofyan, A.; Ridwan, R.; Hassim, H. A.; Respati, A. N.; Wardani, W. W.;

Sadarman, Astuti, W. D.; Jayanegara, A. 2021. Effects of different lactic acid

bacteria groups and fibrolytic enzymes as additives on silage quality: A

meta-analysis. In Bioresource Technology Reports. 14: 100654. DOI: 10.1016/j.biteb.2021.100654

18. Kolar, S.;

Vranic, M.; Bozic, L.; Bosnjak, K. 2022. The effect of maize crop cutting

height and the maturity at harvest on maize silage chemical composition and

fermentation quality in silo. In Journal of Central European Agriculture.

23(2): 290-298. DOI: 10.5513/JCEA01/23.2.3504

19. Kung, L.

Jr.; Treacher, R. J.; Nauman, G. A.; Smagala, A. M.; Endres, K. M.; Cohen, M.

A. 2000. The effect of treating forages with fibrolytic enzymes on its

nutritive value and lactation performance of dairy cows. In Journal of Dairy

Science. 83(1): 115-122. DOI: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(00)74862-4

20. Kung, L.

Jr.; Cohen, M. A.; Rode, L. M.; Treacher, R. J. 2002. The effect of fibrolytic

enzymes sprayed onto forages and fed in a total mixed ratio to lactating dairy

cows. In Journal of Dairy Science. 85(9): 2396-2402. DOI:

10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(02)74321-X

21. Kung, L.

Jr.; Moulder, B. M.; Mulrooney, C. M.; Teller, R. S.; Schmidt, R. J. 2008. The

effect of silage cutting height on the nutritive value of a normal corn silage

hybrid compared with Brown midrib corn silage fed to lactating cows. In Journal

of Dairy Science. 91(4): 1451-1457. DOI: 10.3168/jds.2007-0236

22. Lewis, A.

L.; Cox, W. J.; Cherney, J. H. 2004. Hybrid, maturity, and cutting height Interactions

on corn forage yield and quality. In Agronomy Journal. 96: 267-274. DOI:

10.2134/agronj2004.2670

23. Lynch, J.

P.; OʼKiely, P.; Waters, S. M.; Doyle, E. M. 2012. Conservation characteristics

of corn ears and stover ensiled with the addition of Lactobacillus plantarum

MTD-1, Lactobacillus plantarum 30114, or Lactobacillus buchneri 11A44.

In Journal of Dairy Science. 95(4): 2070-2080. DOI: 10.3168/jds.2011-5013

24. Lynch, J.

P.; Baah, J.; Beauchemin, K. A. 2015. Conservation, fiber digestibility, and

nutritive value of corn harvested at 2 cutting heights and ensiled with

fibrolytic enzymes, either alone or with a ferulic acid esterase-producing

inoculant. In Journal of Dairy Science. 98(2): 1214-1224. DOI:

10.3168/jds.2014-8768

25. Muck, R. E.;

Nadeau, E. M. G.; McAllister, T. A.; Contreras-Govea, F. E.; Santos, M. C.;

Kung, L. Jr. 2017. Silage review: recent advances and future uses of silage

additives. In Journal of Dairy Science. 101(5): 3980-400. DOI:

10.3168/jds.2017-13839

26. Nair, J.;

Yang, H. E.; Redman, A. A.; Chevaux, E.; Drouin, P.; McAllister, T. A.; Wang,

Y. 2022. Effects of a mixture of Lentilactobacillus hilgardii,

Lentilactobacillus buchneri, Pediococcus pentosaceus and fibrolytic enzymes

on silage fermentation, aerobic stability, and performance of growing beef

cattle. Translational Animal Science. 6(4): 1-12. DOI: 10.1093/tas/txac144

27. Neylon, J.

M.; Kung, L. Jr. 2003. Effects of cut height and maturity on the nutritive

value of corn silage for lactating cows. In Journal of Dairy Science. 86(6):

2163-2169. DOI: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(03)73806-5

28. NRC

(National Research Council). 2001. Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle. 7th

rev. ed. Natl. Acad. Sci., Washington. DC.

29. Oliveira, A.

S.; Weinberg, Z. G.; Ogunade, I. M.; Cervantes, A. A. P.; Arriola, K. G.;

Jiang, Y.; Kim, D.; Li, X.; Gonçalves, M. C. M.; Vyas, D.; Adesogan, A. T.

2017. Meta-analysis of effects of inoculation with homofermentative and

facultative heterofermentative lactic acid bacteria on silage fermentation, aerobic

stability, and the performance of dairy cows. In Journal of Dairy Science.

100(6): 4587-4603. DOI: 10.3168/jds.2016-11815

30. Rebora, C.;

Ibarguren, L.; Barros, A.; Bertona, A.; Antonini, C.; Arenas, F.; Calderón, M.;

Guerrero, D. 2018. Corn silage production in the northern oasis of Mendoza,

Argentina. Revista

de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias . Universidad Nacional de Cuyo.

Mendoza. Argentina. 50(2): 369-375. https://bdigital.uncu.edu.ar/12073.

31. SAS/STAT®.

2004. Versión 9.1 del sistema SAS para Windows, copyright 2004 SAS Institute

Inc., Cary, NC, USA.

32. Sheperd, A.

C.; Kung, L. Jr. 1996. An enzyme additive for corn silage: Effects on silage

composition and animal performance. In Journal of Dairy Science. 79(10):

1760-1766. DOI: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(96)76543-8

33. Silveira

Pimentel, P. R.; dos Santos Brant, L. M.; Vasconcelos de Oliveira Lima, A. G.; Costa

Cotrim, D.; Nascimento, T.; Lopes Oliveira, R. 2022. How can nutritional

additives modify ruminant nutrition? InRevista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias .

Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 54(1): 175-189. DOI:

10.48162/rev.39.076

34. Singh, D.;

Kumar-yadav, S.; Sharma, B.; Malik, T. A.; Kumari, V.; Hassan-Mir, S. 2018. Use

of exogenous fibrolytic enzymes as feed additive in ruminants: A review. In

International Journal of Chemical Studies. 6(6): 2912-2917.

35. Stokes, M.

R. 1992. Effects of an enzyme mixture, an inoculant, and their Interaction on

silage fermentation and dairy production. In Journal of Dairy Science. 75(3):

764-773. DOI: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(92)77814-X

36. Undersander,

D.; Mertens, D.; Thiex, N. 1993. Forage analyses procedures. National Forage

Testing Association. Omaha, NE 68137, USA. p. 139.

https://fyi.extension.wisc.edu/ forage/files/2014/01/NFTA-Forage-Analysis-Procedures.pdf

(Accessed November 2021).

37. Vallejo, L.

H.; Salem, A. Z. M.; Kholif, A. E.; Elghangour, M. M. Y.; Fajardo, R. C.;

Rivero, N.; Bastida, A. Z.; Mariezcurrena, M. D. 2016. Influence of cellulase

or xylanase on the in vitro rumen gas production and fermentation of

corn stover. In Indian Journal of Animal Sciences. 86(1): 70-74.

38. Yitbarek, M.

B.; Tamir, B. 2014. Silage Additives: Review. In Open Journal of Applied

Sciences. 4(5): 258-274. DOI: 10.4236/ojapps.2014.45026

39. Wallace, R.

J.; Wallace, S. J.; Mckain, N.; Nsereko, V. L.; Hartnell, G. F. 2001 Influence

of supplementary fibrolytic enzymes on the fermentation of corn and grass

silages by mixed ruminal microorganisms in vitro. In Journal of Animal

Science. 79(7): 1905-1916. DOI: 10.2527/2001.7971905x

40. Wu, Z.;

Roth, G. 2005. Considerations in managing cutting height of corn silage. Penn

State Cooperative Extension Bulletin DAS 03-72. Department of Dairy and Animal

Science, Pennsylvania State University, University Park. 7 p.

https://extension.psu.edu/considerations-in-managing-cutting-height-of-corn-silage

(Accessed August 2020).