Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 55(2). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2023.

Original article

In

vitro and

in vivo efficacy of Larrea divaricata extract for the management

of Phytophthora palmivora in olive trees

Eficacia

in vitro e in vivo del extracto de Larrea divaricata como alternativa

de manejo de Phytophthora palmivora en plantas de olivo

María de los Ángeles Fernández1,

Magdalena Espino1,

Maria Fernanda Silva1,

Pablo Humberto Pizzuolo1,

Gabriela Susana Lucero1

1Universidad

Nacional de Cuyo. Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Instituto de Biología Agrícola

de Mendoza (IBAM). Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas

(CONICET). Almirante Brown 500. Chacras de Coria. Mendoza. M5528AHB. Argentina

*jboiteux@fca.uncu.edu.ar

Abstract

Phytophthora

palmivora is

a ubiquitous pathogen responsible for “dry branch” disease, causing significant

economic losses in olive trees. Synthetic chemical fungicides are currently used

for the control of P. palmivora. The general concern about the negative

consequences of using synthetic products prioritizes the search for

eco-friendly alternatives. In this context, plant extracts have emerged

as an interesting and promising alternative for crop protection. This work

studies the inhibitory activity of Larrea divaricata extract on P.

palmivora mycelial growth, sporangium and zoospore production. The extract

showed fungicidal activity against P. palmivora mycelial growth at

concentrations over 150 mg mL-1. Specifically, the extract at 50 mg

mL-1 completely suppressed the production of P. palmivora sporangia

and zoospores. The alkaloid piperine in L. divaricata extract showed

antimicrobial activity against P. palmivora mycelial growth. Extract

effectiveness was also evaluated on olive trees in a greenhouse, showing 63% of

disease reduction. These results support the use of L. divaricata extract

as another environmentally friendly tool to be included in an integrated disease

management program for dry branch disease caused by P. palmivora.

Keywords: plant extract, antimicrobial

activity, bioactive compounds, alkaloids, diseases, dry branch, Olea europea

Resumen

Phytophtora

palmivora es

un patógeno responsable de pérdidas económicas en olivo y está involucrado en

la enfermedad “rama seca”. Su control se basa en el uso de fungicidas. Dado el

incremento en la preocupación de la población en las consecuencias negativas

que tiene el uso de estos agroquímicos se hace prioritaria la búsqueda de

alternativas ecocompatibles. En este contexto, los extractos de plantas surgen

como una prometedora alternativa para la protección de los cultivos. En este

trabajo se estudió el efecto inhibidor in vitro del extracto de Larrea

divaricata sobre el crecimiento del micelio, la producción de zoosporangios

y zoosporas de P. palmivora. El extracto inactivó completamente el

crecimiento del micelio del patógeno a concentraciones superiores a 150 mg mL-1,

mientras que a concentraciones de 50 mg.mL-1 fue capaz de inhibir la

producción de zoosporangios y zoosporas. El alcaloide piperina fue detectado en

el extracto de L. divaricata demostrando actividad antimicrobiana. La

eficacia del extracto en plantas de olivo inoculadas con el patógeno se evaluó en

invernáculo. Este ensayo evidenció la potencialidad del extracto en el manejo

de la rama seca del olivo mostrando una eficacia del 63%. Los resultados

obtenidos respaldan el uso del extracto de L. divaricata como una

alternativa ecocompatible dentro de un programa de manejo integrado de

enfermedades de la rama seca del olivo.

Palabras claves:

extractos

vegetales, actividad antimicrobiana, compuestos bioactivos, alcaloides, enfermedades,

rama seca, Olea europea

Originales: Recepción: 26/07/2022 - Aceptación: 14/08/2023

Introduction

The genus Phytophthora

includes more than 100 species among the most destructive plant pathogens

worldwide, causing significant economic losses in agricultura (12, 17, 23, 31). P. palmivora is a

relevant species with a wide host range including pineapple, papaya, oranges,

tomatoes, tobacco, citrus, and olive trees (23).

Since the early 1990s, in the main olive growing area of Argentina, several

plants in different orchards were observed with initial drying of some branches

followed by tree death. P. palmivora, P. nicotianae and P.

citrophthora were collected from soil and roots of those symptomatic olive

tree orchards (17). After a few years,

the disease reached an important regional dissemination, with significant

losses.

Current P.

palmivora control is still based on synthetic products such as metalaxyl, fosetyl-Al,

and copper-based fungicides (21, 28, 36).

Nevertheless, these pesticides are associated with several negative

consequences for the environment and human health (6,

10). Furthermore, the extensive application of synthetic products,

such as metalaxyl, has led to the emergence of Phytophthora-resistant strains,

resulting in severe destructive disease in several crops (2, 25). Considering the aforementioned, the

search for greener and safer approaches represents an urgent need as well as a

great challenge.

In recent

decades, novel management strategies have seriously committed to environmental

and human health protection. In this context, plant extracts have emerged as an

interesting and promising alternative for crop protection. Plant extracts from Phlomis

purpurea, Cosmos caudatus, Rosmarinus officinalis, Lavandula

angustifolia, and Salvia officinalis have demonstrated an

outstanding ability to inhibit Phytophthora micelial growth, sporangium,

and zoospores production (25, 29, 33, 36).

Several plant bioactive compounds, including polyphenols, flavonoids, quinones,

tannins, alkaloids, saponins and sterols have shown antimicrobial activity

against phytopathogens (7, 26).

Larrea

divaricata Cav.

is an autochthonous dominant shrub in South America,

broadly growing in Argentina. In folk medicine, extracts of L. divaricata have

been widely used as anti-inflammatory, antirheumatic, dysphoretic, amenagogic,

and antimicrobial compounds (4). Even

though these extracts presented antimicrobial effects against Phytophthora species,

the fungicidal activity, or its efficacy as a potential protective or

curative fungicide, has not yet been reported. Phytochemical reports of our

group have demonstrated the presence of the same phenolic compounds with

antimicrobial activity previously found in L. divaricata extracts, such

as quercetin, luteolin, and cinnamic acid in L. divaricata extracts (3). However, due to the complex nature of plant

extracts, attributing antimicrobial activity to a single, specific bioactive

compound becomes difficult. Along with phenolic compounds, alkaloids are another

relevant group of active substances present in plants.

This work

studied the inhibitory activity of L. divaricata extract against P.

palmivora mycelial growth, sporangia, and zoospore production. Alkaloid

antimicrobial activity in the extract was analyzed against P. palmivora mycelial

growth. In addition, fungicidal activity of L. divaricata extract

against P. palmivora was evaluated in olive trees under greenhouse

conditions.

Material

and Methods

Materials,

chemicals, and standards solutions

V8 agar (V8A)

was prepared using 200 mL commercial V8 juice; 2 g CaCO3; 17 g agar,

and 800 mL distilled water. The salt solution of Chen and Zentmyer was prepared

by mixing Ca (NO3)2 (1.64g) (0.01 M); KNO3

(0.05g) (0.005 M); MgSO4 (0.48 g) (0.004 M); deionized H2O

to 1 liter, and a solution of chelated iron (1 mL) consisting of (g L-1)

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (13.05 g); KOH (7.5 g); FeSO4

(24.9 g) (0.16 M); and deionized water to 1 liter (2).

Analytical

standards, piperine, caffeine, harmaline, nicotine, theophylline, and

theobromine were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Formic acid

(85%) (FA) was obtained from Sintorgan (Bs. As., Argentina). Methanol (MeOH)

and acetonitrile (ACN) of the chromatographic grade were purchased from Baker

(USA). Stock solutions were prepared by dissolving each alkaloid standard at a

concentration of 100 mg L-1 in methanol at 0.1% with FA. Standard

working solutions of each alkaloid at concentrations of 50, 25, 10, and 1 mg L-1

were obtained from stock solutions. All these solutions were stored in

dark-glass bottles at 4°C.

Plant

extract

L. divaricata plants,

taxonomically identified by Cátedra de Botánica de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias de la Universidad Nacional de Cuyo (Mendoza, Argentina), were grown in

a greenhouse. Leaves were collected in the flowering period, and immediately

frozen and lyophilized.

L. divaricata extract was

prepared using the methodology proposed by Boiteux and collaborators (4). Bioactive compounds from L. divaricata leaves

(20 g) were extracted by decoction with distilled water (200 mL) in an

autoclave for 45 min at 121°C. Then the extract was filtered and the volume

reduced by boiling at 20 mL. Finally, the extract was centrifuged and stored at

4°C.

Pathogen

The P.

palmivora isolate was obtained from rotted rootlets of olive trees from

comercial plantations in the province of Catamarca, Argentina (15), and identified by morphological and

molecular characterization (17). This

isolate was maintained on clarified V8 agar.

Inhibitory

activity of L. divaricata extracts

The fungistatic

or fungicidal activity of L. divaricata extract against P. palmivora was

evaluated according to the method proposed by Mahmoudi

(2017). Agar discs (4 mm in diameter) colonized by the pathogen P.

palmivora (grown on V8 agar, 24°C, 5 days old) were placed at the center of

Petri dishes containing V8A with different concentrations of L. divaricata extract

(0; 50; 100; 150; 300; 500 and 700 mg mL-1). A positive control

using a commercial fungicide metalaxyl+mancozeb (RIDOMIL GOLD 68 WG, 4 g de

metalaxyl + 64 g de mancozeb, Syngenta) was included at the recommended

concentration (metalaxyl 0.25 mg mL-1 for Phytophthora species).

The Petri dishes were kept at 25±2°C for 4 days. After the incubation period,

discs of P. palmivora from treatments showing total inhibition were

transferred to plates containing V8A and incubated for 4 days at 25±2°C.

Fungitoxicity of each extract concentration was assessed against mycelial

growth. Thus, the plates showing P. palmivora growth indicated a

fungistatic effect, while absent growth denoted fungicidal action of the L.

divaricata extract. Each treatment was performed in triplicate and the test

was repeated three times.

Effect

of L. divaricata extract on P. palmivora sporangia and zoospores

production

The effect of L.

divaricata extract on P. palmivora sporulation was evaluated in

vitro. Petri dishes containing 6 mL of Chen and Zentmyer solutions (11) were amended with L. divaricata extract

to a final concentration of 0; 1; 5; 10; 25; 50; 100; 150; 300; 500, and 700 mg

mL-1. Subsequently, three agar discs colonized with P. palmivora mycelia

(4 mm in diameter, 5 days old) were placed in the extract solutions. A positive

chemical control, commercial fungicide metalaxyl+mancozeb was included at the

concentration described in the previous section. Each treatment was performed

in triplicate and the assay was repeated three times. Petri dishes were incubated

at 25 ± 2°C for 4 days under fluorescent cool-white light for sporangia

induction. Agar discs were stained and fixed with acid fuchsin in 85% lactic

acid. The number of sporangia per agar disk was counted using an optical

microscope (200X). Results were expressed as inhibition percentage of sporangia

production using equation 1.

Inhibition

(%)= [(C - T)/C] * 100

where:

C and T = P.

palmivora sporangia number of control (without treatment) and treatments, respectively

The effect of L.

divaricata extract on P. palmivora zoospore production was

determined after the incubation period, when the sporangium was induced to

release zoospores by chilling at 4°C for 20 min, then rewarming at 25°C for 20

min. A drop of the suspensión (5 μL) was placed on a glass slide, and zoospores

were counted using an optical microscope (200X). Each treatment was performed

in triplicate and the assay was repeated three times. Then, inhibition

percentage of zoospore production of P. palmivora was determined as follows

2:

Inhibition

(%)= [(C - T)/C] * 100

where:

C and T = the

number of P. palmivora zoospores for control (without treatment) and

treatments, respectively

Determination

of alkaloids from L. divaricata extract

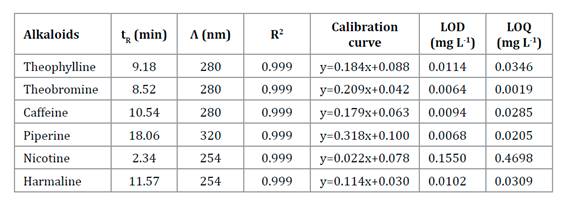

Alkaloids

(theophylline, theobromine, caffeine, piperine, nicotine, and harmaline) were

determined using a HPLC-MWD system (Dionex Ultimate 3000 Softron GmbH, Thermo

Fisher Scientific Inc., Germering, Germany). The detector was a Dionex MWD-3000

(RS) model. To process the obtained data Chromeleon 7.1 software was used. HPLC

separations were carried out in Zorbax SB-Aq column (4.6 mm × 150 mm, 5 μm)

Agilent Technologies. Ultrapure water with 0.1% FA (A) and ACN (B) were used as

mobile phases. Alkaloids were separated using the following gradient: 02.7 min,

5% B; 2.710.7 min, 30% B; 10.7-11 min, 35% B; 1115 min, 50% B; 1515.5 min, 50%

B: 15.516 min 30% B; 16-16.5 min 5% B; 16.517 min 5% B. The mobile phase flow

was 1 mL min-1. The column temperature was held at 20°C and the

sample injection volume was 5 μL. Working wavelengths for the different

analytes were 254 nm, 280 nm, 320 nm, and 370 nm. Alkaloids in L. divaricata

extract were identified and quantified after the comparison of retention

times (tR) and absorbance values of detected peaks in the solvent with those

obtained by injection of pure standards of each analyte. Alkaloid concentration

was expressed as mg L-1.

Analytical

quality parameters were used to assess procedure performance with the selected

conditions. The linearity of the calibration curve was tested by plotting the

área of reference compounds at six concentrations between 0.5 mg L-1

and 100 mg L-1 using a least-squares linear regression model. For

all target compounds, correlation coefficients of calibration equations were

> 0.999.

The limit of

detection (LOD) and limit of quantitation (LOQ) were calculated following the

International Union for Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC).

Antimicrobial

activity of individual alkaloids

The inhibitory

effect of individual alkaloids identified by the HPLC-MWD system in L.

divaricata extract was evaluated against P. palmivora using the

solid agar bioassay. Thus, a 4 mm disc of P. palmivora was placed in the

center of Petri dishes containing V8A amended with the alkaloids at the

concentration found in L. divaricata extract. Control plates were

performed simultaneously, in the growth medium without alkaloid. Petri dishes

were incubated at 25±2°C for 4 days. Each treatment was performed in triplicate

and the assay was repeated three times. After incubation, the P. palmivora colony

area was measured using AxioVision 4.8 software. Results were expressed as

inhibition percentage of mycelial growth using equation (3)

Inhibition

(%)= [(C - T)/C] * 100

where:

C and T = the P.

palmivora colony area (cm2) of control and treatments,

respectively

Disease

control in the bioassay

In vivo effect of L.

divaricata extract was evaluated with one-year-old olive plants (Olea

europaea L., var. Arauco) obtained from a commercial nursery. The assay was

performed following the methodology proposed by Vettraino

et al. (2009). P. palmivora inocula was prepared by mixing 20

mL millet seeds with 150 mL V8 broth in 250 mL flasks. Then, the flasks were

sterilized twice and inoculated with P. palmivora (10 mycelial discs of

8 mm diameter, grown on V8 agar per flask). The flasks were incubated for 1

month in the dark at 25°C. After incubation, millet seed inoculum (20 g L-1)

was added to the soil of olive plants. Control treatments only contained

sterile millet seeds with V8 broth (20 g L-1). To stimulate zoospore

release and disease development, pots were flooded for 48 h, then water excess

was drained off. Afterwards, L. divaricata extract was added to one

treatment, leaving control with only the extract. Experimental treatments were

as follows: (A) inoculated soil with P. palmivora and (B) inoculated

soil with P. palmivora plus L. divaricata extract at 50 mg mL-1.

Controls were performed as pathogen uninoculated soil plus L. divaricata extract

(50 mg mL-1) (C), and only soil (D). For each treatment, five

replicates were performed and the whole assay was repeated twice. The

occurrence of symptoms was observed weekly during the six months, and

percentage of dead plants was calculated at the end of the experiment. After

the assay, P. palmivora was reisolated from roots on a selective V8

medium (15).

Statistical

analysis

One-way ANOVA

was performed for in vitro and in vivo assays using InfoStat for

Windows (2020) software to determine significant differences. The Tukey test (P

< 0.05) was used for multiple comparisons of means.

Results

Inhibitory

activity of L. divaricata extracts

Interestingly,

all studied concentrations (50; 100; 150; 300; 500 and 700 mg mL-1)

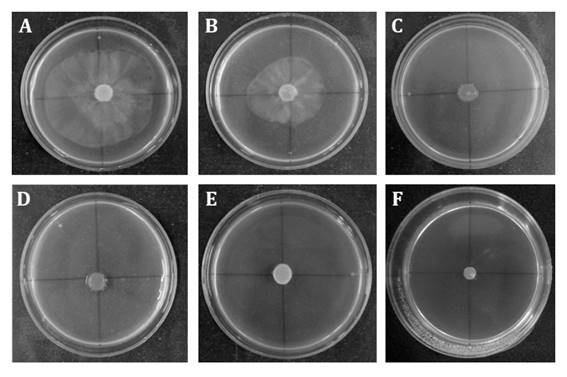

reduced mycelial growth of P. palmivora. Figure 1,

shows 50 and 100 mg mL-1 extracts had a fungistatic effect, whereas

higher concentrations showed fungicidal activity.

Figure 1. Fungistatic

and fungicidal activity of L. divaricata extracts at different

concentrations (A: control; B:50; C:100; D:150; E:300;

F:500 and G:700 mg mL-1) on P. palmivora mycelial growth.

Figura 1. Efecto

fungicida y fungistático del extracto de L. divaricata a diferentes

concentraciones (A: control; B:50; C:100; D:150;

E:300; F:500 and G:700 mg mL-1) sobre el crecimiento miceliar de P.

palmivora.

Effect

of L. divaricata extract on P. palmivora sporangia and zoospores

production

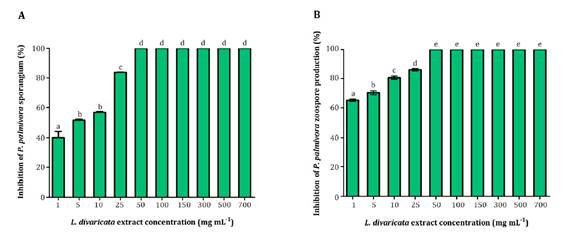

Sporangia and

zoospore production of P. palmivora were inhibited by L. divaricata extract

(1; 5; 10; 25; 50; 100; 150; 300; 500 and 700 mg mL-1). Inhibition

was dose-dependent. Figure 2 shows all bioextract

concentrations were able to inhibit P. palmivora number of sporangia and

zoospores to varying degrees.

Different letters indicate significant statistical

differences according to Tukey test, α < 0.05.

Letras distintas indican diferencias significativas

para tets de Tukey, α < 0,05.

Figure 2. Effect

of L. divaricata extract on P. palmivora sporangia (A), and

zoospore production (B) at different concentrations.

Figura 2. Efecto

de diferentes concentraciones del extracto de L. divaricata sobre la

producción de zoosporangios (A) y zoosporas (B) de P. palmivora.

Interestingly,

at the lowest concentration evaluated (1 mg mL-1), the extract

inhibited 40% and 60% of sporangia and zoospore production, respectively.

Noteworthy is that 50 mg mL-1 of the extract completely suppressed

sporangia and zoospore production.

Determination

of alkaloids from L. divaricata extract

Piperine,

caffeine, harmaline, nicotine, theophylline and theobromine in L. divaricata

extract were determined by chromatographic method HPLC MWD. Table

1 shows analytical quality parameters. All of them showed a linear range

from the LOQ up to at least 100 mg L-1.

Table

1. Analytical figure of merit for alkaloids

analysis by HPLC-MWD method.

Tabla 1. Cifras

de mérito analítico para el análisis de alcaloides mediante HPLC-MWD.

tR:

retention time; Λ: wavelength; R2: coefficient of determination; LOD: limit of detection;

LOQ: limit of quantitation.

tR:

tiempo de retención; Λ: longitud de onda; R2: coeficiente de determinación; LOD:

límite de detección; LOQ: límite de cuantificación.

The only

alkaloid detected was piperine; the other five analytes were not detected,

considering the analytical methodology used. Piperine concentration was 44.02

mg mL-1.

Alkaloid

antimicrobial activity by solid agar bioassay

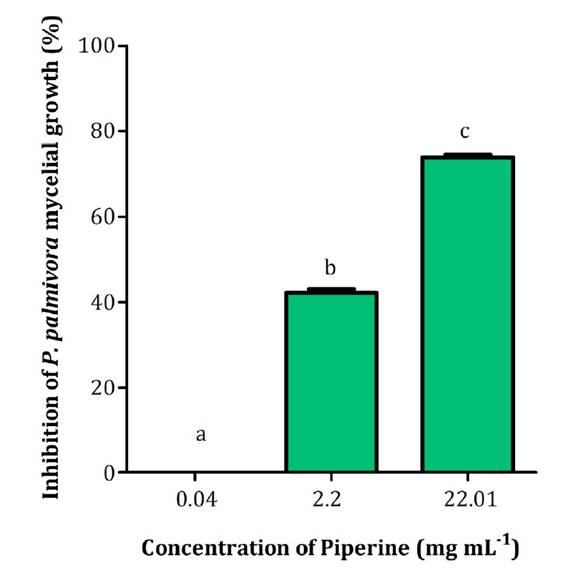

Since the

natural concentration of piperine in L. divaricata extract at 50 mg mL-1

was 2.20 mg mL-1, the biological activity of this alkaloid was

determined at 0.04, 2.20 and 22.01 mg mL-1. As shown in figure

3, the highest inhibition observed for piperine was 75% at 22.01 mg mL-1.

Different letters indicate significant statistical differences

according to the Tukey test, α < 0.05.

Letras distintas indican diferencias significativas para

test de Tukey, α < 0,05.

Figure 3. Effect

of piperine on P. palmivora mycelial growth at different concentrations.

Figura 3. Efecto

de diferentes concentraciones de piperina sobre el crecimiento miceliar de P.

palmivora.

Interestingly, a

10-fold lower piperine concentration (2.20 mg mL-1) achieved 42%

inhibition.

Disease

control in the greenhouse

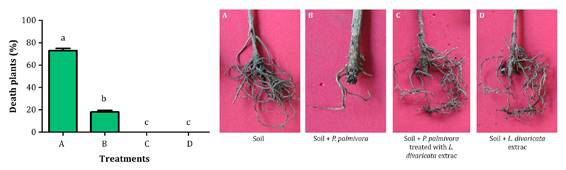

Inoculated soil

with P. palmivora showed 73% dead plants (treatment A). When the soil

was inoculated with P. palmivora plus L. divaricata extract at 50

mg mL-1, total dead plants percentage was only 27% (treatment B) (figure 4).

Different letters indicate significant statistical

differences according to the Tukey test, α < 0.05.

Letras distintas indican diferencias significativas

entre los tratamientos según test de Tukey, α < 0,05.

Figure 4. Percentage

of dead olive plants after treatments at 120 days (A: soil infected with P.

palmivora; B: soil infected with P. palmivora plus L. divaricata extract

at 50 mg mL-1; C: soil with L. divaricata extract; D: only

soil.

Figura 4. Porcentaje

de plantas de olivo muertas después de 120 días del tratamiento (A: suelo

inoculado con P. palmivora; B: suelo inoculado con P. palmivora y

tratado con extracto de L. divaricata a una concentración de 50 mg mL-1;

C: suelo tratado con extracto de L. divaricta; D: suelo solo sin tratar

ni inocular.

These results

highlight the control potential of L. divaricata extract. Control

efficacy of the extract against P. palmivora was 63% (1). Remarkably, no significant differences were

observed between merelysoil (D) and soil containing only the extract of L.

divaricata (C). In all cases, P. palmivora was re-isolated from the

inoculated plants.

Discussion

The current

study evaluated the efficacy of L. divaricata extract for control of P.

palmivora in vitro and in olive trees under greenhouse conditions. Plant

extracts, their bioactive compounds and the ability to inhibit pathogens or

provide medicinal properties have always been of great interest to researchers.

L. divaricata extracts are a rich source of bioactive compounds against

a wide range of microorganisms (1). In

this sense, there is scarce information on the chemical composition and

antimicrobial activity of individual compounds against Phytophthora species.

A previous study by our group reported that four plant extracts showed

antimicrobial activity against P. palmivora mycelial growth, with L.

divaricata extract being the most effective (3).

However, to the best of our knowledge, the fungicidal or fungistatic effect of L.

divaricata extract against P. palmivora mycelial growth has not been

reported yet. In this work, the extract showed fungistatic effect at a

concentration between 50 and 100 mg mL-1, and fungicidal effect

between 150 and 700 mg mL-1.

Different

studies have reported the fungicidal activity of L. divaricata extracts

against different pathogen species. Vogt et al.

(2013) studied the efficacy of L. divaricata organic extracts

against Fusarium graminearum, F. solani, F. verticillioides and

Macrophomina phaseolina. F. graminearum and M. phaseolina were

completely inhibited at 0.25 mg mL-1 of L. divaricata chloroform

extract (33). Hapon

et al. (2017) demonstrated that 200 mg mL-1 of L.

divaricata extract inhibited mycelial growth of Botrytis cinerea (94%)

(13). Interestingly, in this work, a

considerably lower concentration of L. divaricata extract was able to

completely inhibit P. palmivora growth.

The asexual

stages, including sporangia and zoospore, are the main propagules involved in

the rapid spread of P. palmivora. Therefore, evaluating the efficacy of

extracts in controlling these asexual structures is of utmost importance.

Particularly, in our study, L. divaricata extract showed inhibitory

activity on both sporangia formation and zoospore production of P. palmivora.

Salehan et al. (2013) reported that Cosmos

caudatus aqueous extract at 200 mg mL-1 inhibited 37% sporangia

formation and 23% zoospore production of P. palmivora (29). Widmer and Laurent

(2006) demonstrated that plant extracts of Rosmarinus officinalis, Lavandula

angustifolia and Salvia officinalis at 250 mg mL-1 were able

to inhibit zoospore production of P. capsici, P. megakarya and P.

palmivora (35). In line with these

studies, our results also highlight the efficacy of L. divaricata extract

in inhibiting sporangia and zoospore production of P. palmivora.

In view of the

above, L. divaricata extract represents a great alternative for the in

vitro control of P. palmivora. Noteworthy is that the antimicrobial

activity of L. divaricata extract has been related with the presence of

phenolic compounds (3). In this study,

piperine was the only alkaloid found in the extract by HPLC-MWD analysis. This

alkaloid is a bioactive component with outstanding biological properties such

as antitumoral, anti-inflammatory, antifungal and antimicrobial (14, 20, 30).

Several studies

have documented the antibacterial activity of piperine against Escherichia

coli, Klebsiella pneumonia, Salmonella enterica, Staphylococcus

aureus, S. epidermidis, Enterococcus faecalis and Bacillus

subtilis (9, 16, 22, 27, 37). Marques et al. (2010) reported antifungal

activity of this compound against Cladosporium cladosporioides and C.

sphaerospermum (19). Moon et al. (2016) demonstrated that piperine

inhibited mycelial growth and aflatoxin production of Aspergillus flavus (24). Wang et al.

(2020) demonstrated the fungicidal activity of piperine against Rhizoctonia

solani, Fusarium graminearum, Phomopsis adianticola, Alternaria

tenuis, Phytophthora capsici and Gloeosporium theaesinensis.

Piperine at 0.1 mg mL-1 inhibited mycelial growth of P. capsici at

42% (35). These results agree with those

presented in this work, where piperine at 2.20 mg mL-1 inhibited P.

palmivora mycelial growth by 42 %. To the best of our knowledge, this

constitutes the first report on antimicrobial activity of piperine against P.

palmivora. Interestingly, we found that the inhibitory activity of L.

divaricata extract against P. palmivora was higher than piperine used

at the same concentration. This results indicate that piperine could partially

explain extrat total bioactivity against this pathogen. Unfortunately, no

studies have used piperine in the concentration range tested in our study

against P. palmivora. Considering that plant extracts are complex

matrices, it is logical to assume that different compounds of L. divaricata secondary

metabolism, could be active against several plant pathogens.

As seen in our in

vitro studies, the extract was also effective when the biological activity

was assessed on healthy olive plants artificially inoculated with P.

palmivora under greenhouse conditions. In the latter case, the number of

dead plants was significantly reduced compared to non-inoculated plants.

Previous studies have also demonstrated the efficacy of plant extracts in

controlling soilborne pathogens (5, 34). Bowers et al. (2004) showed that synthetic

cinnamon oil, pepper and cassia extracts reduced P. nicotianae populations

on infected Catharanthus roseus (L.) plants under greenhouse conditions

(5). Wang et

al. (2019) demonstrated that zedoary turmeric oil has excellent

antifungal activity against P. capsica, inoculated on detached cucumber

leaves (34). These results are consistent

with those presented in this work, where L. divaricata extract showed

control activity against P. palmivora in olive plants.

Conclusion

This work

highlights the potential of L. divaricata extract for sustainable

management of P. palmivora. The extract obtained had an effective

inhibitory activity on mycelial growth, sporangia and zoospore production of

this pathogen. We also demonstrated that the presence of the alkaloid piperine

in the extract, together with other phenolic compounds, contributes to

antimicrobial activity. These results support the use of L. divaricata extract

as another environmentally friendly tool for an integrated disease management

programme against dry branch disease caused by P. palmivora. Further

complementary studies are required to evaluate commercial applications and

effects on beneficial soil organisms.

Acknowledgements

The authors

thank the Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica, Consejo

Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Facultad de

Ciencias Agrarias- Universidad Nacional de Cuyo and Secretaría de

Investigación, Internacionales y Posgrado (SIIP)- Universidad Nacional de Cuyo

for the financial support of this work.

1. Abbott, W. S.

1925. A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. Journal of

Economic Entomology. 18: 265-267.

2. Bi, Y.; Cui,

X.; Lu, X.; Cai, M.; Liu, X.; Hao, J. J. 2011. Baseline sensitivity of natural

population and resistance of mutants in Phytophthora capsici to

zoxamide. Phytopathology. 101: 1104-1111.

3. Boiteux, J.;

Vargas, C. S.; Pizzuolo, P.; Lucero, G.; Silva, M. F. 2014. Phenolic

characterization and antimicrobial activity of folk medicinal plant extracts

for their applications in olive production. Electrophoresis. 35: 1709-1718.

4. Boiteux, J.;

Monardez, C.; Fernandez, M. A.; Espino, M.; Pizzuolo, P.; Silva, M. F. 2018. Larrea

divaricata volatilome and antimicrobial activity against Monilinia

fructicola. Microchemical Journal. 142: 1-8.

5. Bowers, J.

H.; J. Locke, C. 2004. Effect of formulated plant extracts and oils on

population density of Phytophthora nicotianae in soil and control of Phytophthora

blight in the greenhouse. Plant disease. 88: 11-16.

6. Céspedes, C.

L.; Alarcon J. E.; Aqueveque, P.; Seigler, D. S.; Kubo, I. 2015. In the search

for new secondary metabolites with biopesticidal properties. Israel Journal of

Plant Sciences. 62: 216-228.

7. Chen, F.;

Long, X.; Yu, M.; Liu, Z.; Liu, L.; Shao, H. 2013. Phenolics and antifungal

activities analysis in industrial crop Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus

tuberosus L.) leaves. Industrial Crops and Products. 47: 339-345.

8. Di Rienzo, J.

A.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M. G.; Gonzalez, L.; Tablada, M.; Robledo, C. W.

InfoStat versión 2020. Centro de Transferencia InfoStat, FCA. Universidad

Nacional de Córdoba. Argentina. http://www.infostat.com.ar

9. Dusane, D.

H.; Hosseinidoust, Z.; Asadishad, B.; Tufenkji, N. 2014. Alkaloids modulate

motility, biofilm formation and antibiotic susceptibility of uropathogenic Escherichia

coli. PLoS ONE, 9.

10. El-Sayed, A.

S.; Ali, G. S. 2020. Aspergillus flavipes is a novel efficient

biocontrol agent of Phytophthora parasitica. Biological Control. 140:

104072.

11. Erwin, D.;

Ribeiro, O. 1996. Phytophthora Diseases Worldwide: American

Phytopathological Society 1996. St. Paul. MN. USA.

12. González,

M.; Perez‐Sierra, A.; Serrano, M.; Sánchez, M. 2017. Two Phytophthora species

causing decline of wild olive (Olea europaea subsp. europaea var. sylvestris).

Plant pathology. 66: 941-948.

13. Hapon, M.

V.; Boiteux, J. J.; Fernández, M.; Lucero, G.; Silva, M. F.; Pizzuolo, P. H.

2018. Effect of phenolic compounds present in Argentinian plant extracts on

mycelial growth of the plant pathogen Botrytis cinerea Pers.

14. Hou, X.-F.;

Pan, H.; Xu, L.-H.; Zha, Q.-B.; He, X.-H.; Ouyang, D. Y. 2015. Piperine

suppresses the expression of CXCL8 in lipopolysaccharide-activated SW480 and

HT-29 cells via downregulating the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways.

Inflammation. 38: 1093-1102.

15. Jung, T.;

Blaschke, H.; Neumann, P. 1996. Isolation, identification and pathogenicity of Phytophthora

species from declining oak stands. European Journal of Forest Pathology.

26: 253-272.

16. Khameneh,

B.; Iranshahy, M.; Ghandadi, M.; Ghoochi Atashbeyk, D.; Fazly Bazzaz, B. S.;

Iranshahi, M. 2015. Investigation of the antibacterial activity and efflux pump

inhibitory effect of co-loaded piperine and gentamicin nanoliposomes in

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Drug development and

industrial pharmacy. 41: 989-994.

17. Lucero, G.;

Vettraino, A.; Pizzuolo, P.; Stefano, C. D.; Vannini, A. 2007. First report of Phytophthora

palmivora on olive trees in Argentina. Plant pathology. 56.

18. Mahmoudi, E.

2017. Antifungal effects of Foeniculum vulgare Mill. Herb essential oil

on the phenotypical characterizations of Alternaria alternata Kessel.

Journal of Essential Oil Bearing Plants. 20: 583-590.

19. Marques, J.

V.; de Oliveira, A.; Raggi, L.; Young, M. C. M.; Kato, M. J. 2010. Antifungal

activity of natural and synthetic amides from Piper species. Journal of

the Brazilian Chemical Society. 21: 1807-1813.

20.

Martinez-Sena, M. T.; de la Guardia, M. F.; Esteve-Turrillas, A.; Armenta, S.

2017. Hard cap espresso extraction and liquid chromatography determination of

bioactive compounds in vegetables and spices. Food chemistry. 237: 75-82.

21. McLeod, A.;

Masikane, S. L.; Novela, P.; Ma, J.; Mohale, P.; Nyoni, M.; Stander, M.;

Wessels, J.; Pieterse, P. 2018. Quantification of root phosphite concentrations

for evaluating the potential of foliar phosphonate sprays for the management of

avocado root rot. Crop protection. 103: 87-97.

22. Mirza, Z.

M.; Kumar, A.; Kalia, N. P.; Zargar, A.; Khan, I. A. 2011. Piperine as an

inhibitor of the MdeA efflux pump of Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of

medical microbiology. 60: 1472-1478.

23. Mohamed

Azni, I. N. A.; Sundram, S.; Ramachandran, V.; Seman, Abu I. 2017. An in

vitro investigation of Malaysian Phytophthora palmivora isolates and

pathogenicity study on oil palm. Journal of Phytopathology. 165: 800-812.

24. Moon, Y.-S.;

Choi, W.-S.; Park, E.-S.; Bae, I. K.; Choi, S.-D.; Paek, O., S.; Kim, H.; Chun,

H. S.; Lee, S. E. 2016. Antifungal and antiaflatoxigenic

methylenedioxy-containing compounds and piperine-like synthetic compounds.

Toxins. 8: 240.

25. Neves, D.;

Caetano, P.; Oliveira, J.; Maia, C.; Horta, M.; Sousa, N.; Salgado, M.;

Dionísio, L.; Magan, N.; Cravador, A. 2014. Anti-Phytophthora cinnamomi activity

of Phlomis purpurea plant and root extracts. European journal of plant

pathology. 138: 835-846.

26. Piccirillo,

C.; Demiray, S.; Silva Ferreira, A. C.; Pintado, M. E.; Castro, P. M. L. 2013.

Chemical composition and antibacterial properties of stem and leaf extracts

from Ginja cherry plant. Industrial Crops and Products. 43: 562-569.

27. Quijia, C.

R.; Chorilli, M. 2020. Characteristics, biological properties and analytical

methods of piperine: A review. Critical reviews in analytical chemistry. 50:

62-77.

28. Rodrigo, S.;

Santamaria, O.; Halecker, S.; Lledó, S.; Stadler, M. 2017. Antagonism between Byssochlamys

spectabilis (anamorph Paecilomyces variotii) and plant pathogens:

Involvement of the bioactive compounds produced by the endophyte. Annals of

Applied Biology. 171: 464-476.

29. Salehan, N.

M.; Meon, S.; Ismail, I. S. 2013. Antifungal activity of Cosmos caudatus extracts

against seven economically important plant pathogens. International Journal of

Agriculture and Biology. 15.

30.

Tharmalingam, N.; Kim, S.-H.; Park, M.; Woo, H. J.; Kim, H. W.; Yang, J. Y.;

Rhee, K.-J.; Kim, J. B. 2014. Inhibitory effect of piperine on Helicobacter

pylori growth and adhesion to gastric adenocarcinoma cells. Infectious

agents and cancer. 9: 43.

31. Tomura, T.;

Molli, S. D.; Murata, R.; Ojika, M. 2017. Universality of the Phytophthora mating

hormones and diversity of their production profile. Scientific reports. 7:

1-12.

32. Vettraino,

A.; Lucero, G.; Pizzuolo, P.; Franceschini, S.; Vannini, A. 2009. First report

of root rot and twigs wilting of olive trees in Argentina caused by Phytophthora

nicotianae. Plant disease. 93: 765-765.

33. Vogt, V.;

Cifuente, D.; Tonn, C.; Sabini, L.; Rosas, S. 2013. Antifungal activity in

vitro and in vivo of extracts and lignans isolated from Larrea

divaricata Cav. against phytopathogenic fungus.

Industrial crops and products. 42: 583-586.

34. Wang, B.;

Liu, F.; Li, Q.; Xu, S.; Zhao, X.; Xue, P.; Feng, X. 2019. Antifungal activity

of zedoary turmeric oil against Phytophthora capsici through damaging

cell membrane. Pesticide biochemistry and physiology. 159: 59-67.

35. Wang, J.;

Wang, W.; Xiong, H.; Song, D.; Cao, X. 2020. Natural phenolic derivatives based

on piperine scaffold as potential antifungal agents. BMC chemistry. 14(1):

1-12.

36. Widmer, T.

L.; Laurent, N. 2006. Plant extracts containing caffeic acid and rosmarinic

acid inhibit zoospore germination of Phytophthora spp. pathogenic to Theobroma cacao. European Journal of

plant pathology. 115: 377.

37. Zarai, Z.;

Boujelbene, E.; Salem, N. B.; Gargouri, Y.; Sayari, A. 2013. Antioxidant and

antimicrobial activities of various solvent extracts, piperine and piperic acid

from Piper nigrum. Lwt-Food science and technology. 50: 634-641.