Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 55(2). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2023.

Original article

Volunteer

soybean (Glycine max) interference in bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) crops:

ethoxysulfuron and halosulfuron critical level of damage and selectivity

Interferencia

de la soja (Glycine max) voluntaria en el cultivo del frijol (Phaseolus

vulgaris): nivel crítico de daño y selectividad de los herbicidas

etoxysulfuron y halosulfuron

Fortunato De

Bortolli Pagnoncelli Jr.1,

Patricia

Bortolanza Pereira2,

Denise Roberta

Rader3,

Rodrigo Biedacha4,

Leandro Galon5,

Adriano

Bresciani Machado6

1Basf

Brasil, Desenvolvimento de Traits - Basf - Luis Eduardo Magalhães. Bahia. Brasil.

2Universidade

Tecnológica Federal do Paraná- UTFPR. Via do Conhecimento. s/n

- KM 01 - Fraron. Pato Branco. Paraná. Brasil. 85503-390.

3Cargill

- Av. Marechal Floriano Peixoto. 495. Bairro Paraguai. Maracaju. Mato Grosso do

Sul. Brasil. 79150-000.

4Coopavel

-Avenida Padre Ivo Zolet- 880. Bom Sucesso do Sul- Paraná- Brasil. 85515-000.

5Federal

University of Fronteira Sul. Campus Erechim. Laboratory of Sustainable Management

of Agricultural Systems. 99700-970. Erechim. Rio Grande do Sul. Brazil.

6CEDEP

AGRO. Rua Marechal Floriano Peixoto. 1675. Renascença. Paraná. Brasil. 85610-000.

*trezzi@utfpr.edu.br

Abstract

This study aimed

to determine the negative impact of volunteer soybean plants on bean crop yield

and the tolerance of bean genotypes to the herbicides ethoxysulfuron and

halosulfuron. To determine the impact of volunteer soybean plants on bean

crops, a field experiment was developed, with sub-sub-plots, and four

replications. The main plots contained two bean cultivars, while the sub-plots

received two soybean sowing times (0 and 7 days after the beans had been sown),

while the sub-sub-plots contained five soybean plant densities (0, 5, 10, 20,

and 40 plants m-2). The tolerance of the bean genotypes was

evaluated with two experiments in a completely randomized design with three

replications. They were arranged in a 28 x 3 factorial design (bean genotypes x

herbicide doses). Each soybean plant per m2 reduced bean crop yield

by 4%. The recommended doses of ethoxysulfuorn and halosulfuorn resulted in

tolerance levels above 70% for all the studied bean genotypes.

Keywords: competitive

interference, volunteer soybean, tolerance, herbicides

Resumen

Este estudio

determinó el impacto negativo de las plantas voluntarias de soja en el rendimiento

del frijol y la tolerancia de genotipos de frijol a los herbicidas

etoxysulfuron y halosulfuron. Para determinar el impacto de la soja en el

cultivo de frijol, se desarrolló un experimento de campo, en sub-sub-parcelas,

con cuatro repeticiones. Las parcelas principales contenían dos cultivares de

frijol; las subparcelas tenían dos tiempos de siembra de soja (0 y 7 días

después del frijol); las sub-subparcelas contenían 5 densidades de soja (0, 5,

10, 20 y 40 plantas m-2). La tolerancia de los genotipos de frijol

se evaluó con dos experimentos en un diseño completamente al azar con tres

repeticiones, en un factorial 28 x 3 (genotipos de

frijol x dosis). Cada planta de soja por m2 redujo un 4% el

rendimiento del frijol. Las dosis recomendadas de etoxysulfuron y halosulfuron

resultaran niveles de tolerancia superiores al 70%.

Palabras clave: interferencia

competitiva, soja voluntaria, tolerancia, herbicidas

Originales:

Recepción: 06/08/2023 - Aceptación: 21/11/2023

Introduction

Bean crops are

among the most commonly cultivated species in the world. According to the FAO

(2022) (8), in 2020 bean cultivation

occupied 34.8 million ha, with a total production of 27.55-million-tons. This

resulted in a mean global yield of 791.5 kg ha-1 (8), even though some genotypes have a potential yield

of over 4 ton ha-1 (5). Low

productivity, in many of the areas where bean crops are cultivated, can be a

result of the poor adaptation of some genotypes and environmental conditions,

such as extreme temperature and drought stress, but it is mainly due to grain

loss from pests, diseases and weeds.

Bean plants

present a fast development cycle and a low ability to accumulate biomass, which

makes them susceptible to competition from weed plants. The literature reports

that a mixed infestation of weeds can reduce grain yield by up to 80% (3, 9), in addition to lowering the commercial

quality of bean grains.

The importance

of intensive farming systems has increased in regions with suitable soil and

climatic conditions, since they improve the use of these areas, creating the

possibility of cultivating more than one crop per year. In Brazil, the use of

early and very early soybean cultivars as the first and second crop in a

rotation is becoming more normal. Fallow, as a practice to prevent the effects

of Asian soybean rust (Phakopsora pachyrhizi) in some Brazilian states,

has constrained the sowing of off-season soybean, which results in the

intensification of maize, sorghum and bean crops in this period. Natural

soybean grain dehiscence or the incorrect adjustment of the harvesting machine

can result in the emergence of soybean plants in the middle of a bean crop

(second crop), which can interfere with crop growth and yield.

Volunteer corn

plants can reduce bean yield between 27 and 35% per corn plant m-2

emerging at the same time as the bean plants. Between 4.6 and 9.7 plants / m-2

can reduce bean yield by 50% (1). To

date, the impact generated by volunteer soybean plants competing with bean

plants is unknown, but they are suspected to have the potential to be highly

competitive since there are many morphological similarities between the two

species, which could intensify the competition for the same ecological niche (20). In addition, chemical management in this

situation is hampered by the high selectivity of the herbicides for both

cultures.

The herbicides

ethoxysulfuron and halosulfuron, which inhibit the acetolactate synthase (ALS)

enzyme, are registered in Brazil for the control of volunteer soybean plants in

bean crops (4) and are considered

efficient (16). The success of these

herbicides depends on how selective they are for different bean cultivars and

how efficiently they can control soybean plants presenting greater genetic

variability. The identification of the bean genotype response to herbicides is fundamental

to determining its use in weed management; it is also essential for improvement

programs aimed at the selection of herbicide-tolerant genotypes.

The objective of

this study was to determine the impact of the interference of soybean plants on

the grain yield of different bean genotypes and the tolerance of these vean

genotypes to the herbicides ethoxysulfuron and halosulfuron.

Materials

and methods

Experimental

site

The experiments

were carried out in a greenhouse and in the field at the Federal University of

Technology - Paraná, Campus Pato Branco (UTFPR-PB) (26°10’31.6’’ S and

52°42’28.01’’ W) at an altitude of 740m. The climatic region is considered a

climatic transition between the cfa/cfb climates (both rainy and hot temperate

climates, the former is humid in all seasons and hot in the summer; while the

latter is humid in all seasons with moderately hot summers), according to the

Köppen climate classification (12). The

soil used in both experiments is classified as an Oxisol (table 1).

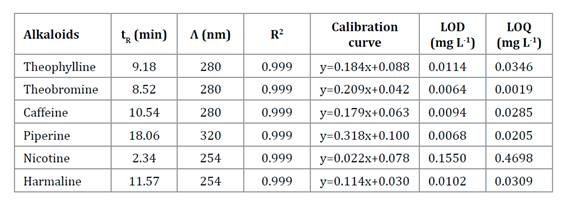

Table

1. Physicochemical characteristics of the

soil where the experiments were carried out.

Tabla 1.

Características físico-químicas del suelo donde se llevaron a cabo los

experimentos.

1/

Organic Matter (g dm-3); 2/ Phosphorus (mg dm-3);

3/ Potassium (cmolc dm-3); 4/ Cation exchange

capacity; 5/ Soil pH; 6/ Exchangeable acidity (cmolc dm-3).

1/

Materia Orgánica (g dm-3); 2/ Fósforo (mg dm-3);

3/ Potasio (cmolc dm-3); 4/ Capacidad de intercambio

catiónico; 5/ pH del suelo; 6/ Acidez intercambiable (cmolc

dm-3).

For the

greenhouse experiments, the collected soil was sieved in a 5 mm mesh sieve and

deposited in 5L polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pots. Irrigation was carried out

manually twice a day. The greenhouse conditions during the experimental period

were 20 to 30°C and 60 to 90% relative air humidity. For the field experiment,

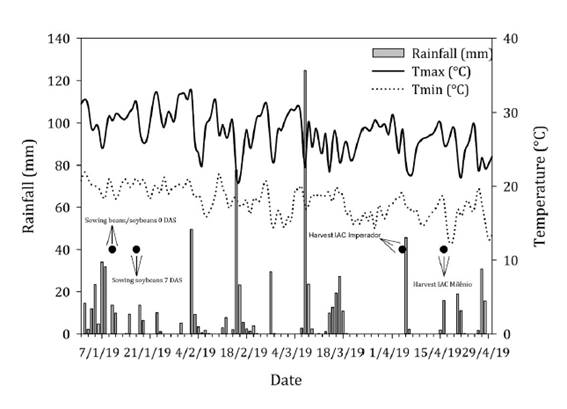

the climate conditions during the experimental period are presented in figure

1.

Source: Simepar (Meteorological System of Paraná).

Fuente de información: Simepar (Sistema

Meteorológico de Paraná).

Figure 1.

Rainfall (■), Minimum (-) and maximum (---) temperature during the development

of the experiment in 2019 in Pato Branco, PR, Brazil.

Figura 1.

Lluvia (■), temperatura mínima (-) y máxima (---) durante el desarrollo del

experimento en 2019 en Pato Branco, Paraná, Brasil.

Soybean

plant interference in bean plants

A field

experiment was set up, using a randomized block experimental design with

sub-sub plots and four repetitions. In the main plots, two bean genotypes were

implanted with distinct morphophysiological characteristics: IAC Imperador,

with a determinate growth habit, upright position and a 75-day cycle; and IAC Milênio,

with an indeterminate growth habit, semi-upright position and a 95-day

development cycle. The sub-plots comprised two soybean sowing times, 0 and 7

days after bean sowing, and in the sub-sub-plots, five soybean plant densities

were implemented (0, 5, 10, 20 and 40 plants per m-2). The soybean

plant genotype used was P95R51, with an indeterminate growth habit and a

120-day development cycle.

The

sub-sub-plots consisted of five 5m long lines, with a 0.45m interval between

them. The usable area of the sub-sub-plots was composed of the three central

lines, excluding 0.5 m at each end. Bean sowing was carried out using a no-till

sower, with a desired plant density of 280.000 pl ha-1 for both

genotypes. The seeds were treated with a 100g i.a. dose of fipronil +

pyraclostrobin + thiophanate-methyl per 100 kg of seeds. The base fertilization

used was 269 kg ha-1 of the 8-28-16 (N-P2O5-K2O)

formulation. When the plants were in the V4 phase, topdressing was

carried out with 60 kg ha-1 urea (46% N). Soybean sowing was carried

out manually and after the plants had emerged, excess plants were removed to

homogenize the densities set for the treatments.

Weeds were

manually removed during the experimental period. Insect control was carried out

with thiamethoxan+lambda-cyhalothrin (30.87 g i.a. ha-1), acefate+

aluminum silicate (975,5 g i.a. ha-1), and

beta-cyfluthrin+imidacloprid (81.37 g i.a. ha-1). Disease control

was carried out with fentin hydroxide (250 g i.a. ha-1),

prothioconazole+trifloxystrobin (162,5 g i.a. ha-1), and mancozebe

(2250 g i.a. ha-1).

When the bean

plants were fully grown, 10 plants from the usable area (5.4 m2) of

each sub-sub plot were selected to determine plant height (ESTm), first pod

insertion height (AIPV), number of pods per plant (NVP), number of grains per

pod (NGV) and 1000-grain mass (MMG). Bean grain yield (REND) for each genotype

was determined by harvesting and then threshing the plants of the usable area

of each sub-sub-plot, the resulting grains were weighed and the grain mass

humidity determined and corrected to 13%.

Tolerance

of the bean genotypes

In the

greenhouse, two experiments were set up in a completely randomized experimental

design, with three replications and two factors. The first experiment was

developed with the herbicide ethoxysulfuron, while the second investigated the

herbicide halosulfuron. In both experiments, the first factor contained 28 bean

genotypes, which included: IAC Imperador, IAC Milênio, Jalo

Precoce, BRS Radiante, ANFP 110, IPR Colibri, BRS Esteio,

IPR Uirapuru, IPR Tuiuiú, IAC Harmonia, BRS Esplendor,

IPR Campos Gerais, IPR Tiziu, IPR Juriti, BRS Talismã,

IPR Siriri, IPR Tangará, IAPAR 81, IPR Andorinha, IPR Corujinha,

IPR El dourado, IPR Grauna, IPR Chopim, IPR Saracura,

IPR Garça, IPR Maracanã, ANFC 9, and IPR Gralha. The

second factor was defined by the doses of each herbicide applied to each

experiment. The doses applied of the herbicide ethoxysulfuron were 0, 45, and

90 g ha-1, while the doses applied of halosulfuron were 0, 80, and

160 g ha-1. Four seeds were placed in each pot; after emergence and

establishment, excess plants were removed leaving only two plants.

Herbicide was

applied when 50% or more plants presented an expanded third trifoliate leaf,

using a CO2 pressurized back sprayer equipped with XR 110.02

flat-fan nozzles. The volume of the mixture used was 200 L ha-1,

with a 3.6 km h-1 application speed. For the herbicide halosulfuron,

the mixture included a nonylphenol ethoxylate surfactant at a 0.5% v/v

concentration.

Twenty-eight

days after application, the tolerance of the bean plants was determined using a

scale in which 100 corresponded to the absence of herbicide symptoms and 0

corresponded to plant death intermediate values were ascribed according to

discolouration, atrophy and growth reduction.

Statistical

analysis

The data were

submitted to variance analysis (p ≤ 0.05) using the R

language (2018). For the bean tolerance evaluation experiments, the means

were grouped using the Scott-Knott test (p ≤ 0.05), using the R language (2018). For the competition experiment, when

the means of the qualitative data were significant, they were compared using

the Tukey (p ≤ 0.05) test (21), while the

means of quantitative data were fitted to a linear polynomial (Equation 1),

three-parameter logistic (Equation 2) and rectangular hyperbola (Equation 3)

models, using the Sigmaplot software version 12.0 (24).

Y = A * B + X

Y = A / [1 + (X

/ D50) ^ ]

YL = (A * X) /

(D50 + X)

where

Y = the dependent

variable

X = the soybean

density

A = the Y value

when the X value tends to 0

B = the curve

slope

D50 = the soybean

plant density needed to reduce the dependent variable by 50%

YL = the grain

yield loss (%).

For the

rectangular hyperbola model, the relation between parameters A and D50

results in the i parameter, which represents the yield loss when the

soybean density is 1 plant m-2 and is considered the critical damage

level (6).

Results and discussion

Interference

of soybean plants in bean plants

The variance

analysis indicated significance for only the bean genotype isolated factor

regarding the ESTm, GVG, and MMG variables. For the AIPV variable, significance

was observed for the simple effects of bean genotype and soybean density, while

the VAG variable presented significance for the simple effects of bean

genotype, soybean density and soybean establishment time. For the REND

variable, significance was observed for soybean density, bean genotype

interaction and the simple effect of soybean establishment time.

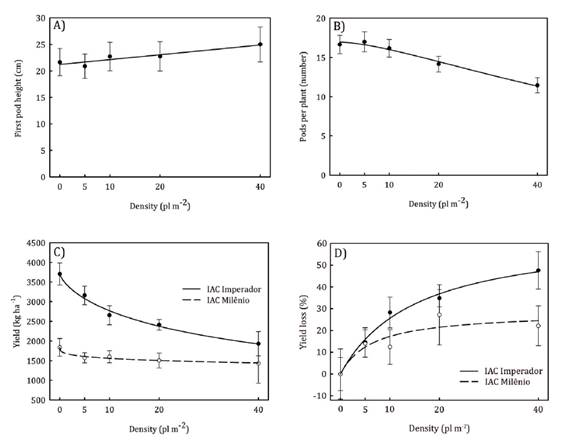

An increase in

bean AIPV was observed with the increase in soybean density, which was 20% in relation

to the control, without plants, when the soybean density was 40 pl m-2

(figure 2, page 113).

A) first pod insertion height (cm), B) Pods per

plant (number), C) Grain yield (%), (D) Bean yield loss (%). Each point

represents a mean of three replications and the bars represent the mean

standard error. Parameters are presented in table

2 and table 3 (page 114).

A) altura de inserción de la primera vaina (cm), B)

Vainas por planta (número), C) Rendimiento de grano (%), (D) Pérdida de

rendimiento (%) de frijol. Cada punto representa la media de tres repeticiones

y las barras representan el error estándar medio. Los parámetros se presentan

en la tabla 2 y tabla 3 (pág. 114).

Figure 2. Impact

of soybean plant density, with two different establishment times (0 and 7 days

after bean sowing) and of two bean cultivars (IAC Milênio and IAC Imperador).

Figura 2. Impacto

de la densidad de plantas de soja, de dos tiempos de establecimiento (0 y 7

días después de la siembra del frijol) y de dos cultivares de frijol (IAC

Milênio e IAC Imperador).

However, the

number of pods per plant reduced with the increase in soybean plant density,

reaching a 30% reduction with the 40 pl m-2 density. As reported by Machado et al. (2015), increased weed density

negatively impacted the number of pods per bean plant, which was a result of

the reduction in the number of branches per plant. Competition between plants

promotes a greater search for light, favouring etiolation and the development

of branches in the upper third of the plant to the detriment of the lower

third, which causes a higher AIPV.

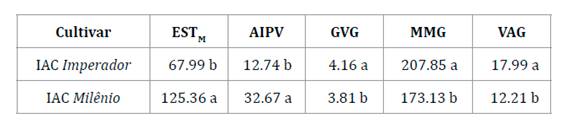

The IAC Imperador

genotype presented lower ESTm (46%) and AIPV (61%) when compared with IAC Milênio,

while the IAC Milênio genotype presented lower GVG, MMG and VAG (8, 17,

and 32%, respectively) in comparison with IAC Imperador (table

2, page 113).

Table

2. Height of adult plants (cm) (ESTM),

First pod insertion height (cm) (AIPV), Grains per pod (n) (GVG), 1000 grain

mass (g) (MMG) and Pods per plant (n) (VAG) for beans plants of the cultivars

IAC Imperador and IAC Milênio.

Tabla 2. Altura

de las plantas maduras (cm) (ESTM), Altura de inserción de la primera vaina

(cm) (AIPV), Granos por vaina (n) (GVG), Masa de mil granos (g) (MMG), Vainas

por planta (n) (VAG) de plantas de frijol de los cultivares IAC Imperador e IAC

Milênio.

1/

Means followed by the same letter in the same column did not differ according

to the Tukey test (p≤0.05). The data represents the means of all densities and

times of soybean sowing.

1/

Medias seguidas de la misma letra en la misma columna no difieren en la prueba

de Tukey (p≤0,05). Los datos representan las medias de todas las densidades y

épocas de siembra de soja.

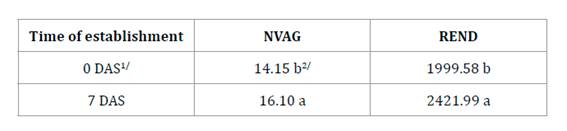

The differences

observed between the genotypes are due to the intrinsic characteristics of each

material. When the soybean plants were established simultaneously with the vean

plants, lower NVAG (14%) and REND (21%) were observed when compared with the

results obtained from soybean plants established 7 days after the bean sowing (table 3).

Table

3. Pods per plant (n) (VAG) and grain yield

(Kg ha-1) (REND) of beans with two different times of soybean crop

establishment.

Tabla 3.

Vainas por planta (n) (VAG) y rendimiento de grano (Kg ha-1) (REND)

de frijol en dos tiempos de establecimiento del cultivo de soja.

1/ Days after

soybean sowing. 2/ Means followed by the same letter in the same

column did not differ in the Tukey test (p≤0.05). The data represents the means

of all densities and the bean cultivars.

1/ Dias después de

la siembra de soja. 2/ Medias seguidas de la misma letra en la misma

columna no difieren en la prueba de Tukey (p≤0,05). Los datos representan las

medias de todas las densidades y los cultivares de frijol.

The weed

interference potential tends to be greater when these plants are established in

the area simultaneously or before the commercial crop plants, as has been

observed in several works on different species both cultivated and weeds (14, 18). The plants that establish first in the

environment present some advantages regarding the allocation of resources,

guaranteeing a greater competitive potential (20).

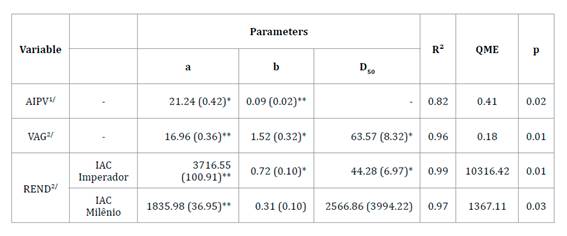

The maximum

grain yield values for each of the bean genotypes were distinct, as revealed by

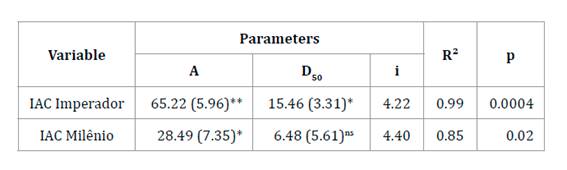

the “a” parameter value (table 4).

Table

4. Equation parameters to determine the

impact of soybean plant densities on the first pod insertion height (AIPV)

(cm), number of pods per plant (VAG) and grain yield (REND) (kg ha-1)

of bean plants.

Tabla 4.

Parámetros de la ecuación para determinar el impacto de las densidades de

plantas de soja en la altura de inserción de la primera vaina (AIPV) (cm),

número de vainas por planta (VAG) y rendimiento de grano (REND) (kg ha-1)

de plantas de frijol.

*

and ** significant at 5 and at 1%

probability, respectively; 1/ Linear polynomial model. 2/

Three-parameter logistic model.

*

y ** significativos al 5 y al 1% de

probabilidad, respectivamente; 1/ Modelo de polinomio lineal. 2/

Modelo logístico de tres parámetros.

The maximum

yield of the IAC Imperador genotype was 3716 kg ha-1, and was

reduced by 48% with a soybean density of 40 pl m-2. The IAC Milênio

genotype presented a maximum grain yield of 1836 kg ha-1, lower

than that of IAC Imperador, however, it was reduced by only 22% with the

maximum soybean density (figure 2D, page 113).

The NCD of

soybean plant interference in the beans crop was higher than that caused by the

interference of the Brachiaria plantaginea (0.4 to 0.7) (11), but

similar to that caused by Euphorbia heterophylla (2.4 to 5.5) (14), and lower than that caused by maize plants

to beans (27 to 35) (1). This highlights

the high damage caused by soybean plants to bean crops. As reported by Radosevich et al. (2007), the higher the

morphologic similarity between the plants is, the higher the competition

between them. In the soybean crop, for example, the NCD can vary from 0.97 to

36.42, depending on the weed type and its establishment time (18).

Despite the

different potentials for soybean plant interference in the bean genotypes, the

level of damage (NCD) observed was similar between them, that is, a soybean

plant per m² was able to reduce the grain yield of both genotypes by

approximately 4% (table 5). This occurred because the NCD

value (parameter i) corresponds to the tangent of the rectangular

hyperbola angle in the curve region where the infesting density is close to

zero (6). Therefore, parameter i does

not detect the negative impact on the gain yield at higher densities, and this

impact is greater in the cultivar IAC Imperador than IAC Milênio.

However, i is still a useful parameter, since it estimates losses at low

densities, which are usually close to the economic damage level (18).

Table 5. Equation

parameters for determining the impact of soybean plant densities on grain yield

loss (%) in bean plants.

Tabla 5.

Parámetros de la ecuación para determinar el impacto de las densidades de

plantas de soja en la pérdida de rendimiento de grano (%) de las plantas de

frijol.

*

and ** significant at 5 and 1% probability,

respectively; 1/ Rectangular hyperbola.

*

e ** significativos al 5 y al 1% de

probabilidad, respectivamente; 1/ Hipérbola rectangular.

Bean

genotype tolerance

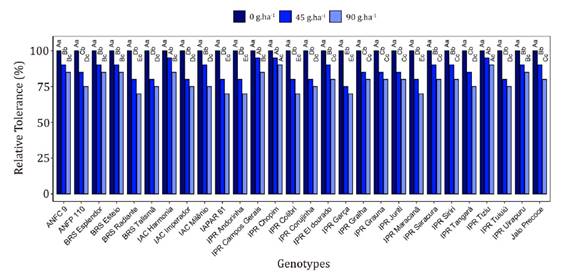

A significant

effect was observed for the interaction between dose and bean genotype for both

herbicides. Regardless of the herbicide, reduced tolerance was observed for all

the genotypes with the increase in herbicide dose. With the 45 g ha-1

dose of ethoxysulfuron, the genotypes IAC Harmonia, IPR Campos gerais,

IPR Chopim and IPR Tiziu stood out for having high tolerance

levels, over 95%, compared with the other genotypes (figure 3,

page 116).

*Uppercase

letters compare cultivars within each dose, while lowercase letters compare

doses within each cultivar using the Scott-Knott test (p ≤ 0.05).

*Las

letras mayúsculas comparan los cultivares dentro de cada dosis, mientras que

las letras minúsculas comparan las dosis dentro de cada cultivar usando la

prueba de Scott-Knott (p ≤ 0,05).

Figure 3. Relative

tolerance (%) of 28 bean cultivars to the different doses of the herbicide

ethoxysulfuron 28 days after application (DAA).

Figura 3. Tolerancia

relativa (%) de 28 cultivares de frijol a diferentes dosis de ethoxysulfuron 28

días después de su aplicación (DAA).

When the dose

was increased to 90 g ha-1, only the genotypes IPR Chopim and

IPR Tiziu presented high tolerance levels, over 90%. With the 45 g ha-1

dose of ethoxysulfuron, the genotype IPR Garça showed lower tolerance

than the others, 75%. When the dose was increased to 90 g ha-1, the

genotypes BRS Radiante, IPR 81, IPR Andorinha, IPR Colibri,

IPR Garça and IPR Maracanã showed greater sensitivity to the

herbicide, with a 70% maximum tolerance.

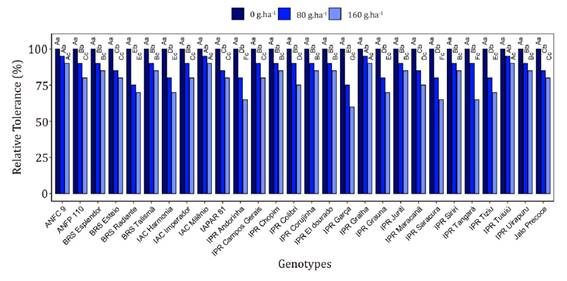

With both doses

of the herbicide halosulfuron, 80 and 160 g ha-1, the genotypes ANFC 9, IAC Milênio,

IPR Gralha and IPR Tuiuiu stood out for presenting a higher

tolerance than the other gynotypes, reaching over 90% (figure 4,

page 116).

*Uppercase

letters compare cultivars within each dose, while lowercase letters compare

doses within each cultivar using the Scott-Knott test (p ≤ 0.05).

*Las

letras mayúsculas comparan los cultivares dentro de cada dosis, mientras que

las letras minúsculas comparan las dosis dentro de cada cultivar usando la

prueba de Scott-Knott (p ≤ 0,05).

Figure 4. Relative

tolerance (%) of 28 bean cultivars to different doses of the herbicide

halosulfuron 28 days after application (DAA).

Figura 4. Tolerancia

relativa (%) de 28 cultivares de frijol a diferentes dosis de halosulfuron 28

días después de su aplicación (DAA).

It is necessary

to highlight that none of the genotypes that showed higher tolerance to

ethoxysulfuron presented the same reaction to halosulfuron. However, some

genotypes such as IAC Harmonia and IPR Tiziu presented a high

tolerance to ethoxysulfuron, and an intermediate tolerance to halosulfuron.

Only the genotypes BRS Radiante and IPR Garça presented a low

tolerance to halosulfuron in the 80 g ha-1 dose, reaching the 75%

level. When the dose was increased to 160 g ha-1, the genotypes IPR Andorinha,

IPR Garça, IPR Saracura, and IPR Tangará showed lower tolerance

than the other genotypes, which was either equal to or lower than 65%.

Highly variable

responses to both herbicides were observed for the bean genotypes, similar

results were found by Soltani et al. (2015)

for the same herbicides. In that study, the authors observed that the level of

injury provided by halosulfuron would barely pass 15%, however, the damage to

some genotypes resulting from ethoxysulfuron could reach 70%. In the present

study, the mean tolerance to ethoxysulfuron for all the genotypes was

86.07±5.83 (mean ± standard deviation) (45 g ha-1) and 78.39±6.24

(90 g ha-1) and the mean tolerance to halosulfuron was 87.14±5.84

(80 g ha-1) and 78.75±8.78 (160 g ha-1). This shows that

there was a similar mean tolerance to both herbicides; however, differences

were observed between the cultivars. In addition, the standard deviation for

the herbicide halosulfuron for the 160 g ha-1 dose was the highest, suggesting

a greater response variability by the genotypes to the higher doses of this

herbicide when compared with ethoxysulfuron. The differential tolerance of bean

genotypes to different herbicides such as saflufenacil, sulfentrazone,

clomazone, dimethenamid, and metolachlor, applied pre-emergence (7, 10, 17, 22, 23) or to the herbicides

chlorimuron and imazethapyr applied post-emergence (19)

has also been observed. The differential tolerance between genotypes could be

related mainly to the tolerance mechanism. The main mechanism involved in the

tolerance of cultivated plants is metabolization through enzymes belonging to

the cytochrome P450. In fact, the involvement of these proteins has been

suggested in bean tolerance to the herbicides ethoxysulfuron and halosulfuron (13). However, differences regarding the interception

and absorption of herbicides, mainly related to the plant morphology (leaf

angle, quantity and quality of the epicuticular wax), as well as differences

regarding translocation between plants may also justify the differential

tolerance between genotypes (2, 15).

Increased doses

resulted in a reduction in plant tolerance to both herbicides in all genotypes.

This suggests that suitable management practices must be adopted to prevent a

reduction in the tolerance of the cropped species. Situations that require

increased doses, such as the management of a difficult control plant inside the

crop, must be avoided. Likewise, taking care when applying the herbicides, by

not overfilling the spray bar, for example, is a recommended practice to

prevent loss of herbicide selectivity.

It is very

difficult to estimate the threshold of injury to the plants in the vegetative

phase, the level over which grain yield loss occurs, since the correlation

between an early level of damage and yield loss is influenced by several

factors, such as the herbicide action mechanism, environmental conditions that

determine plant recovery, and management practices adopted, among others. If we

consider that the plants can recover from an observed injury at 28 DAA of the

herbicide up to the tolerance threshold of 70%, it could be assumed, given the

data presented in this study, that the use of the label recommended dose of

both herbicides, ethoxysulfuron and halosulfuron, would allow the recovery of

the plants without hampering their productive potential. However,

ethoxysulfuron doses greater than the ones recommended on the label would not

be tolerated by the genotypes BRS Radiante, IPR Colibri, IPR 81,

IPR Andorinha, IPR Garça and IPR Maracanã. Likewise,

halosulfuron doses over the ones recommended would not be tolerated by the

genotypes BRS Radiante, IAC Harmonia, IPR Tiziu, IPR Tangará,

IPR Andorinha, IPR Graúna, IPR Saracura and IPR Garça,

since they could harm the productive potential of the plants.

In the tests

that evaluated the tolerance of bean genotypes, a highly variable response to

the herbicides was observed. This highlights the importance of a good

management plan that considers the tolerance of bean genotypes to herbicides

when cropping beans and soybean in succession. The cultivation of bean

genotypes with lower tolerance to the herbicides (BRS Radiante, IPR Colibri,

IPR 81, IPR Andorinha, IPR Garça and IPR Maracanã to

ethoxysulfuron and BRS Radiante, IAC Harmonia, IPR Tiziu,

IPR Tangará, IPR Andorinha, IPR Graúna, IPR Saracura and

IPR Garça to halosulfuron) could result in grain losses. However, field

experiments comparing bean genotypes have to be performed to obtain further

information on grain yield.

According to the

data analysis, the impact of soybean plants on bean grain yield is high. Among

the genotypes used in the competition study, IAC Milênio presented a

comparatively high tolerance to halosulfuron; however, its tolerance to

ethoxysulfuron can be considered intermediate to low, depending on the dose

used. The genotype IAC Imperador presented intermediate tolerance to

halosulfuron; however, its tolerance to ethoxysulfuron was low.

The behavioural

difference of bean genotypes in relation to the different herbicides should be

highlighted. Despite the mean behaviour of all genotypes being similar in

relation to the herbicides (86 and 87% for the label recommended dose and 78

and 79% for double the recommended dose, respectively, for ethoxysulfuron and

halosulfuron), different responses from the same genotype to each of the

herbicides were observed. This occurred for the genotype IPR Tiziu,

which presented high tolerance to ethoxysulfuron, but had a low tolerance to

halosulfuron, when compared to the other genotypes. This emphasizes the importance

of knowing the tolerance of the genotype before choosing the herbicide.

Conclusions

Each soybean

plant is capable of causing a 4% reduction in bean plant grain yield,

regardless of the establishment time of the soybean plants or the bean genotype.

Calculating the level of economic damage by considering both economic and

biological variables is recommended to assist with decision-making to control

soybean plants infesting bean crops.

The bean

genotypes displayed a highly variable response to the herbicides ethoxysulfuron

and halosulfuron; however, when the label recommended dose of the herbicides

was used, the tolerance levels observed were over 70%. Knowledge of this

variable response to the herbicides is important as a warning to farmers and

technicians and can be used in vean breeding programs. An increase in each of

the herbicide doses promotes an increase in bean plant damage. Therefore, care

should be taken when applying herbicides, mainly by avoiding over-spraying.

Acknowledgements

This study was

financially supported by UTFPR and the company Corteva Agriscience and

benefitted from CNPq (IC and Productivity) and CAPES (doctorate program)

grants. We also appreciate the Soil Laboratory at UTFPR Campus Pato Branco for

carrying out the soil analyses.

1. Aguiar, A. C.

M. 2018. Interferência e nível de dano econômico de milho voluntário em feijão.

Dissertação de Mestrado. Programa de Pós-graduação em Agronomia, Agricultura e

Ambiente. UFSM, Campus Frederico Westphalen. 111 p.

2. Azania, C. A.

M.; Azania, A. A. P. M. 2014. Seletividade de herbicidas. In: Monquero, P. A.

(Org.). Aspectos da biologia e manejo das plantas daninhas. São Carlos: Rima.

217-233.

3. Borchartt,

L.; Jakelaitis, A.; Valadão, F. C. D. A.; Venturoso, L. A. C.; Santos, C. L. D.

2011. Períodos de interferência de plantas daninhas na cultura do

feijoeiro-comum (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Revista Ciência Agronômica.

42(3): 725-734.

4. Brasil.

Agrofit - Sistema de Agrotóxicos Fitossanitários.

https://agrofit.agricultura.gov. br/agrofit_cons/principal_agrofit_cons.

Consultation carried out in 10.07.2022.

5. Castro

Oliveira, M. G.; de Oliveira, L. F. C.; Kusdra, G. D. R. F.; Díaz, J. L. C.

2017. Desempenho Produtivo da Cultivar de Feijão-Comum BRS Esteio em Unidades

Demonstrativas na Região Centro-Sul do Paraná. Boletim de Pesquisa e

Desenvolvimento. (49): 19.

6. Cousens, R.;

Doyle, C. J.; Wilson, B. J.; Cussans, G. W. 1986. Modelling the economics of

controlling Avena fatua in winter wheat. Pesticide Science. 17(1): 1-12.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.2780170102

7. Diesel, F.;

Trezzi, M. M.; Oliveira, P. H.; Xavier, E.; Pazuch, D.; Pagnoncelli Junior, F.

2014. Tolerance of dry bean cultivars to saflufenacil. Ciência e

Agrotecnologia. 38(4): 352-360. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-70542014000400005

8. Food and

Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 2022. FAOSTAT statistical

database. Rome. https://www.fao.org/faostat. Consultation carried out in

10.07.2022.

9. Galon, L.;

Winter, F. L.; Forte, C. T.; Agazzi, L. R.; Basso, F. J. M.; Holz, C. M.;

Perin, G. F. 2017. Associação de herbicidas para o controle de plantas daninhas

em feijão do tipo preto. Revista Brasileira de Herbicidas. 16(4): 268-278.

https://doi.org/10.7824/rbh.v16i4.559

10. Hekmat, S.;

Shropshire, C.; Soltani, N.; Sikkema, P. H. 2007. Responses of dry beans (Phaseolus

vulgaris L.) to sulfentrazone. Crop Protection. 26(4): 525-529.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2006.05.002

11. Kalsing, A.;

Vidal, R. A. 2013. Nível crítico de dano de papuã em feijão-comum. Planta

Daninha. 31(4): 843-850. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-83582013000400010

12. Köppen, W.

1931. Grundriss der Klimakunde. Walter de Gruyter. Berlin. 388p.

13. Li, Z.;

Kessler, K. C.; de Figueiredo, M. R. A.; Nissen, S. J.; Gaines, T. A.; Westra,

P.; Van Acker, R. C.; Hall, C.; Robinson, D.; Soltani, N.; Sikkema, P. H. 2016.

Halosulfuron absorption, translocation, and metabolism in white and adzuki

bean. Weed Science. 64(4): 705-711. https://doi.org/10.1614/WS-D-16-00029.1

14. Machado, A.

B.; Trezzi, M. M.; Vidal, R. A.; Patel, F.; Cieslik, L. F.; Debastiani, F.

2015. Rendimento de grãos de feijão e nível de dano econômico sob dois períodos

de competição com Euphorbia heterophylla. Planta daninha. Viçosa, MG.

Vol. 33(1): 41-48. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-83582015000100005

15. Oliveira Jr,

R. S.; Inoue, M. H. 2011. Seletividade de Herbicidas para Culturas e Plantas

Daninhas. IN: Oliveira Jr, R. S.; Constantin, J.; Inoue, M. H. Biologia e

Manejo de Plantas Daninhas. ed. Omnipax. 243-259.

16. Pagnoncelli,

F.; Vidal, R. A.; Trezzi, M. M.; Batistel, S. C.; Gobetti, R. C.; Cavalheiro,

B. M.; Viecelli, M. 2017. Ethoxysulfuron no controle de plantas daninhas na

cultura do feijoeiro comum. Revista

Brasileira de Herbicidas . 16(4): 257-267. https://doi.org/10.7824/rbh.v16i4.550

17. Poling, K.

W.; Renner, K. A.; Penner, D. 2009. Dry edible bean class and cultivar response

to dimethenamid and metolachlor. Weed Technology. 23(1): 73-80.

https://doi.org/10.1614/WT-07-092.1

18. Portugal,

J.; Vidal, R. A. 2010. Definições e terminologia sobre nível crítico de dano

(NCD) na herbologia. In: Vidal, R.A.; Portugal, J.; Skora Neto, F. Nível

crítico de dano de infestantes em culturas anuais. Porto Alegre: Evangraf. p.

8-19.

19. Procópio, S.

O.; Braz, A. J. B. P.; Barroso, A. L. L.; Cargnelutti Filho, A.; Cruvinel, K.

L.; Betta, M.; Braz, G. B. P.; Fraga Filho, J. J. S.; Cunha Júnior, L. D. 2009.

Potencial de uso dos herbicidas chlorimuron-ethyl, imazethapyr e

cloransulam-methyl na cultura do feijão. Planta Daninha. 27(2): 327-336.

https://doi. org/10.1590/S0100-83582009000200016

20. Radosevich,

S. R.; Holt, J. S.; Ghersa, C. M. 2007. Ecology of weeds and invasive plants:

relationship to agriculture and natural resource management. John Wiley &

Sons.

21. R Core Team.

2018. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for

Statistical Computing, Vienna. Austria. Acesso em: 20 jun 2020.

https://www.R-project.org/

22. Sikkema, P.

H.; Shropshire, C.; Soltani, N. 2007. Effect of clomazone on various market

classes of dry beans. Crop Protection. 26(7): 943-947.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2006.08.014

23. Soltani, N.;

Shropshire, C.; Sikkema, P. H. 2015. Response of four market classes of dry

beans to halosulfuron applied postemergence at five application timings.

Agricultural Sciences. 6(2): 247. https://doi.org/10.4236/as.2015.62025

24. Systat

software. N.d. San Jose. California. https://systatsoftware.com/