Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 55(2). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2023.

Original article

Fragmented

areas due to agricultural activity: native vegetation dynamics at crop

interface (Montecaseros, Mendoza, Argentina)

Áreas

fragmentadas por la actividad agrícola: dinámica de la vegetación nativa en su

interfase con cultivos (Montecaseros, Mendoza, Argentina)

Elena María

Abraham2

1Universidad

Nacional de Cuyo. Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Almirante Brown 500. Chacras

de Coria. Luján de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina (CPA M5528AHB).

2Instituto

Argentino de Investigaciones de Zonas Áridas (IADIZA). CONICET. Av. Ruiz Leal

s/n. Parque General San Martín. Mendoza. Argentina. (CP 5500).

*avignoni@fca.uncu.edu.ar

Abstract

Plant

communities fragmented by agricultural activities were analyzed in a 250-ha

area in eastern plains of Montecaseros, Gral. San Martín Department, Mendoza,

Argentina. A phytosociological method assessed different sites along a gradient

of human intervention, from natural environments with no evidence of altered

native vegetation to maximum farming modification, also including cleared and

abandoned fields. Soil analyses supplemented the characterization of six plant

communities. A scrubland physiognomy dominates the area, with species of the

genera Larrea, Atriplex and Lycium. Tillage and crop

abandonment can alter natural factors involved in soil formation, causing

deterioration and exerting selective pressure on species colonizing these

degraded environments. Evaluating natural vegetation before land clearing for

agriculture is essential to assess, through species that indicate environmental

conditions, edaphic limitations hindering crop establishment and affecting

productivity. The conservation of natural communities on private lands destined

for agriculture is valued.

Keywords: plant communities,

abandoned crops, dynamism, habitat fragmentation, soil degradation

Resumen

Se analizaron

comunidades vegetales fragmentadas por actividades agrícolas en un área de 250

ha en las llanuras orientales de Montecaseros, Departamento de Gral. San

Martín, Mendoza, Argentina. Se aplicó el método fitosociológico en sitios a lo

largo de un gradiente de intervención humana, desde ambientes naturales sin

evidencia de vegetación nativa alterada hasta la máxima modificación debido a

la agricultura, incluyendo también parcelas desmontadas y abandonadas. La

caracterización de seis comunidades vegetales se complementó con análisis de

suelo. La fisonomía dominante en la zona es el matorral, con especies de los

géneros Larrea, Atriplex y Lycium. La labranza y el

abandono de cultivos pueden alterar los factores naturales involucrados en la

formación del suelo. Estas actividades causan deterioro y ejercen una presión

selectiva sobre las especies que colonizan estos ambientes degradados. La

evaluación de la vegetación natural antes del desmonte para la agricultura es

fundamental para valorar, a través de especies indicadoras de las condiciones

ambientales, las limitaciones edáficas que dificultan el establecimiento de

cultivos y afectan su productividad. Se pone en valor la conservación de

comunidades naturales en terrenos privados destinados a la agricultura.

Palabras clave: comunidades

vegetales, cultivos abandonados, dinamismo, fragmentación de hábitat, degradación de

suelos

Originales: Recepción: 10/06/2022 - Aceptación: 11/12/2023

Introduction

Plant

biodiversity plays a strategic role in ecosystemic provision of goods and

services for human health and well-being (21).

Agriculture causes changes in these ecosystems involving both productive

activities and consequent effects on the socioeconomic and biophysical

environment. Agriculture requires ecosystem services (water, soil and genetic

diversity) while generating food, fiber and fuel, soil fertility, habitats for

wildlife, landscape and culture, among others (29).

However, the dominant models of agricultural intensification affect natural

resources by generating pollution, fragmentation and degradation, associated

with loss of ecosystem services (33).

Fragmentation of

natural environments consists of disintegrating a continuous landscape into

smaller fractions, separated from one another by a cover matrix resulting from

human activity (9). Replacement of

natural ecosystems for agroecosystems, urbanization, and other infrastructures

increases land vulnerability. Landscape fragmentation levels could be

considered an indicator of soil degradation (28)

generally related to inappropriate agricultural practices, overgrazing, unplanned

urbanization and expansion of agricultura frontier.

In Argentina,

66% of the territory corresponds to arid, semiarid and dry sub-humid areas,

where water and wind erosion affect two million hectares a year (16). In turn, about 47% of agricultural production

comes from drylands under desertification processes (2).

These ecosystems have low capacity for natural regeneration. Degradation

associated with reduced biological and economic productivity is hard to

reverse. Consequently, water and food supplies are affected, threatening

investment and technical development, and causing poverty and rural desertion,

feeding back the originating processes (27).

Mendoza plains,

where the most important agricultural activities take place, belongs to the

Monte Phytogeographic Province, an extensive vegetation unit that occupies

great part of Argentina’s drylands (7).

Given water deficit is the major factor limiting productivity, agriculture is

intensive and irrigated. Productive activities follow an agro-industrial model

in the large irrigated oases of Mendoza, already expanded over non-irrigated

areas. In San Martín (east Mendoza), more than 2200 farms comprise 94000 ha of

private producers, most of them landowners (14).

In Montecaseros, a district of San Martín, viticulture occupies most

agricultural land, where clearing has resulted in a mosaic of landscapes.

Productive crops merge with abandoned crops (with virtually bare soils,

evidence of degradation and low floristic diversity) and fragments of natural

fields (with appropriate native flora coverage preventing erosion processes).

Vegetation is an important component of landscape affected by geomorphology,

soil, climate, and even land use history (35).

Physiognomically, the area reflects environmental heterogeneity. Prosopis

flexuosa DC. woods and other areas representative

of the Monte biodiversity in Montecaseros provide fundamental ecosystem

services, where native plants might constitute reservoirs for pest predators

and crop pollinators.

At local level,

no publications addressing fragmentation in agricultural environments or

floristic-ecological studies are available. Related references in the region

involve ecology, management and conservation of Prosopis woodland (36), flora and vegetation in protected areas (25), vegetation assessment of peripheral oasis

lands (11), and vegetation coverage

classification in San Martín (19).

Considering

background information scarcity in San Martín and the importance of viticulture

for economic and social development, this study aimed to characterize plant

communities in natural and intervened environments, in a representative area of

the fragmentation processes caused by agriculture in Montecaseros district.

Materials

and methods

Study

area

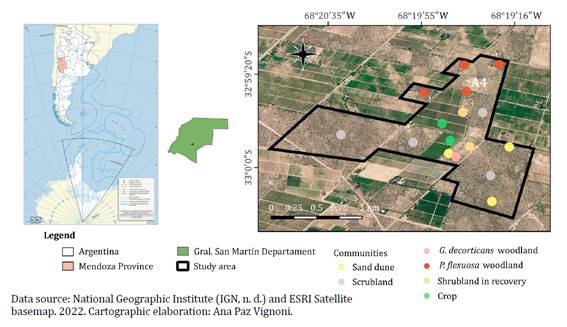

The area

comprises 250 ha in Montecaseros district, General San Martín Department,

Mendoza, Argentina (figure 1), located on the eastern

fluvial-eolian plain of Mendoza (1),

concentrating the greatest agricultural activity of the province. Altitude

ranges between 598 and 644 m a. s. l. Climate is desertic (17), with mean annual temperature of 15°C, mean

annual rainfall reaching 200 mm under a spring-summer regime, and prevalence of

SE winds, frequently warm and dry (föehn type or “Zonda” winds).

Figure 1. Study

area and distribution of communities surveyed.

Figura 1. Área

de estudio y distribución de las comunidades relevadas.

The vegetation

corresponds to the Monte Phytogeographic Province (7),

typical of the Northern District and Central Sub-district of the Monte Desert (26), recently considered within the Septentrional

District according to the latest classification (3).

In natural environments, evergreen shrub-steppe and scrubland are dominant,

represented by species of the genera Larrea, Atriplex and Lycium,

and small relics of Prosopis flexuosa and Geoffroea decorticans woodland

(Gillies ex Hook. & Arn.) Burkart. Grasses develop on open sites with low

tree and shrub coverage. Fixed and semi-fixed sand dunes are frequent, with

bare-root growth and psammophilous plants. Crops have fragmented these natural

vegetation areas, creating ideal conditions for the development of native and

exotic weed species.

Montecaseros

soils are poorly developed Entisols (23, 32)

with strong moisture déficit most of the year. Sandy textures prevail, with

surface or subsurface sites with finer soil layers, suitable for cropping given

groundwater availability. The entire area is affected by land degradation

processes, accelerated by natural water and wind erosion events.

Methodology

Analysis

of plant communities

Areas were

selected by satellite imagery (Google Earth, 2012) and available maps,

representing regions affected by fragmentation processes (figure

1). Research activities were conducted between December 2011 and June 2012.

Maps were made using free access QGIS software, version

3.22.6 (2022).

Plant

communities were studied by the phytosociological method (5), based on criteria of floristically,

physiognomically and ecologically homogeneous sites. Each species was assigned

abundance-dominance and sociability values in every location (24). In total, 87 surveys were conducted, and the

study area was delimited in the field according to community composition and

physiognomy. All plots were 49 m2 except at crop sites (30 m2) and in P.

flexuosa woodland, where surveys were done over a larger area (225 m2).

Additionally, each survey included vegetation stratification, geographic and

altitude coordinates (GPS) and visual assessment of slope decline, water of

dynamic and wind processes, solar exposure and evidence of human activity. Data

were first ordered and analyzed on a comparative table of surveys, and

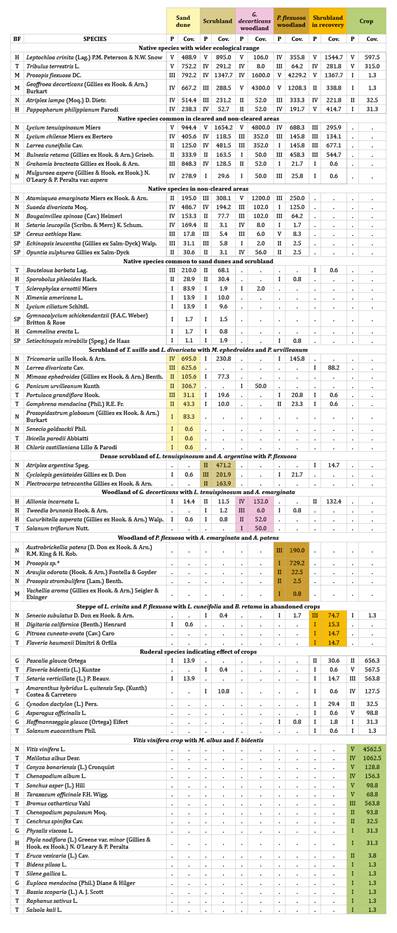

summarized in a synthetic comparative table (table 1),

grouping those species best adjusted to each environment.

Table

1. Survey synthetic comparative table (24).

Tabla 1. Cuadro

comparativo sintético de relevamientos (24).

BF: biological forms (SP: succulent phanerophytes,

G: geophytes, H: hemicryptophytes, M: microphanerophytes, N: nanophanerophytes

and T: therophytes). P: species degree of presence (V: presence>80% of

surveys; IV: 60.1-80%; III: 40.1-60%; II: 20.1-40%; I: <20%). Cov.: global

coverage value (sum of mean species covers divided by total surveys per

community, multiplied by 100). Annex 2 details species with low values of

presence and/or coverage in each community. * Possible hybrid between P.

flexuosa and P. chilensis.

BF: formas biológicas (SP: fanerófitas suculentas,

G: geófitas, H: hemicriptófitas, M: microfanerófitas, N: nanofanerófitas y T:

terófitas). P: grados de presencia de cada especie (V: presencia >80% de los

relevamientos; IV: 60.1-80%; III: 40.1-60%; II: 20.1-40%; I: <20%). Cov.:

valor global de cobertura (suma de las coberturas medias de cada especie dividido el número total de los relevamientos de cada

comunidad por 100). El Anexo 2 detalla las especies con valores escasos de

presencia y/o cobertura en cada comunidad. * Posible híbrido entre P.

flexuosa y P. chilensis.

Categories

describing each group of species (24)

were 1- Exclusive characteristic species (strongly linked to a community,

practically not observed outside) or Preferential characteristic species (with

a wider ecological range but finding an optimum in one community), 2-

Accompanying species (wide ecological range, not related to a particular

community, indifferent) and 3- Accidental species (intruders in a community).

Floristic compositions of non-cleared sites (scrubland) were interpreted as

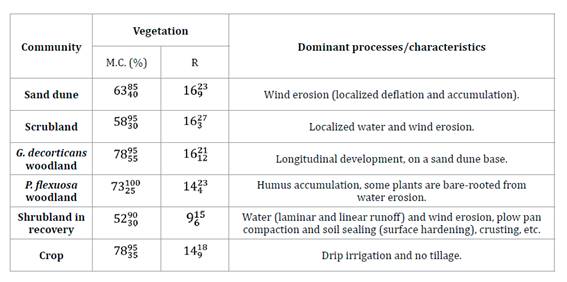

reference to the original natural vegetation. Table 2

synthesizes total mean coverage of each community, floristic richness and

dominant processes.

Table

2. Dominant processes and characteristics

of identified communities.

Tabla 2. Procesos

dominantes y características de las comunidades identificadas.

Total mean coverage (M.C.) expresses mean percentage

of soil covered with vegetation. Richness (R) represents mean number of species

per survey. Superindices and sub-indices show maximum and minimum observed values,

respectively.

La cobertura total media (M.C.) expresa el

porcentaje promedio de suelo cubierto por vegetación. La riqueza (R) representa

el número medio de especies por relevamiento. Superíndices y subíndices

muestran los valores máximos y mínimos observados, respectivamente.

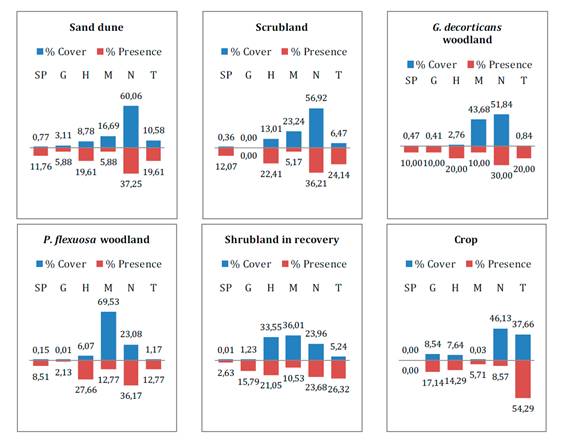

Life form was

analyzed for each species according to perpetuation organ position (22) as succulent phanerophytes or cacti (SP,

plants with thick juicy stems), geophytes (G, plants with underground survival

organs), hemicryptophytes (H, herbs and perennial grasses with renewal buds at

ground level), microphanerophytes (M, trees with renewal shoots from 2 to 8 m),

nanophanerophytes (N, shrubs with renewal buds at less than 2 m height), and

therophytes (T, annual plants). In each community, relative contributions of

every biological form were estimated according to coverage and frequency, and

expressed in histograms or biological spectra (figure 2).

Coverage spectrums were determined after mean coverage values per

abundance-dominance interval of each species (24).

A frequency spectrum considered the number of species of each biological form

over total species in the community.

SP: succulent phanerophytes, G: geophytes, H:

hemicryptophytes, M: microphanerophytes, N: nanophanerophytes and T:

therophytes.

SP: fanerófitas suculentas, G: geófitas, H:

hemicriptófitas, M: microfanerófitas, N: nanofanerófitas y T: terófitas.

Figure 2. Biological

cover and frequency spectra for each community.

Figura 2. Espectros

biológicos de cobertura y frecuencia para cada comunidad.

Taxonomic

determinations

Representative

samples of species found in the area were herborized and taxonomically

identified based on reference specimens from the Mendoza Ruiz Leal Herbarium

(MERL, Argentine Institute for Dryland Research), and monographic works and

publications on Argentina’s regional floras. Regarding nomenclature, we

consulted the Catalog of Vascular Plants of Argentina (38) and the database of Argentine Flora (n. d.),

the International Plant Names Index (n. d.), Tropics organization (n. d.), and

the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (2018).

Recently, a disintegration of the genus Prosopis L. based on molecular

phylogeny has been proposed, followed by a new nomenclatural combination for

American species of the genera Neltuma and Strombocarpa (12). Nevertheless, we keep Burkart’s traditional

classification of Prosopis (6) for

nomenclatural stability, prevailing current use and disadvantageous changes

(31, articles 14, 34 and 56), until acceptance of nomenclatural changes by the

International Committee of Nomenclature.

Soil

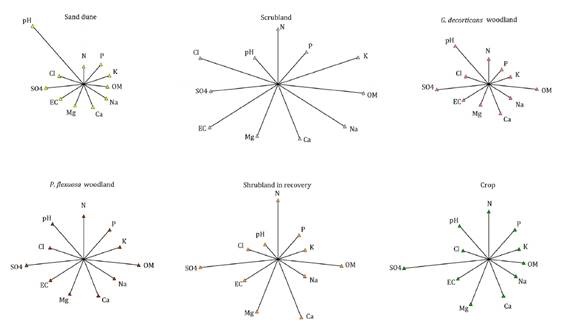

analysis

Soil samples

supplemented environmental descriptions of different communities. After

establishing 16 sites, three samples were removed from a pit dug in each site,

achieving a maximum depth of 1.10 m, totalling 48 samples and including data

from the intermediate layer (0.20 to 0.50 m), where most root activity is

concentrated (table 3, Annex 1). Texture, fertility

(nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and organic matter), salinity (electric

conductivity and sodium adsorption ratio), acidity (pH), ion complex (sodium,

calcium, magnesium, carbonate, bicarbonate, sulfate and chloride) and humidity

were determined for each simple (4).

Results were analyzed with descriptive statistics by InfoStat software version

2020 (8), graphed on star charts for

every community, where each variable is represented by a radius whose length is

the mean value of samples taken from each community (figure 3).

Each graph shows mean values of N: nitrogen, P:

phosphorus, K: potassium, OM: organic matter, Na: sodium, Ca: calcium, Mg:

magnesium, EC: electric conductivity, SO4: sulfates, Cl: chlorides and pH:

hydrogen potential.

En cada uno de los gráficos valores medios de N:

nitrógeno, P: fósforo, K: potasio, OM: materia orgánica, Na: sodio, Ca: calcio,

Mg: magnesio, EC: conductividad eléctrica, SO4: sulfatos, Cl: cloruros y pH:

potencial hidrógeno.

Figure 3. Star

graphs for main edaphic variables analyzed in each community.

Figura 3. Gráficos

de estrellas para las principales variables edáficas analizadas en cada

comunidad.

Results

and discussion

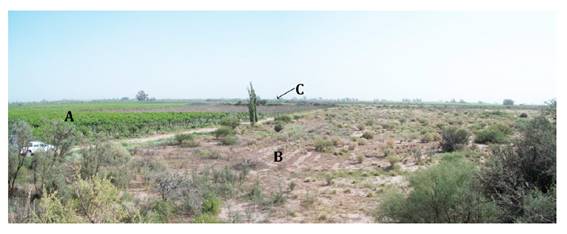

Six plant

communities were identified as sand dunes, scrubland, G. decorticans woodland,

P. flexuosa woodland, shrubland in recovery after crop abandonment, and

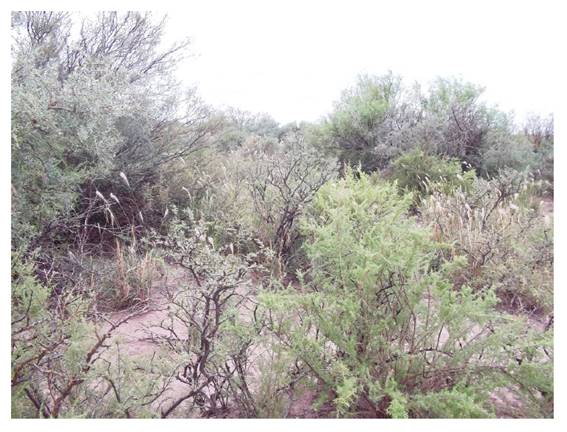

crop (photo 1; table 1; figure

1). Species with wider ecological range (accompanying species) were L.

crinita, T. terrestris, P. flexuosa, G. decorticans,

A. lampa and P. philippianum.

Photo 1. Study

area: A, crop, B, shrubland in recovery and C, non-cleared scrubland.

Foto 1. Área

de estudio: A, cultivo, B, arbustal en recuperación y C, matorral sin

desmontar.

Poor soils in

organic matter and nitrogen had good contents of phosphorus and potassium, and

different levels of salinity. Most of the samples showed mildly alkaline and

non-sodic characteristics (table 3, Annex 1).

Scrubland

of T. usillo and L. divaricata with M. ephedroides

and P. urvilleanum on sand dunes

Sand dunes had

predominant scrub vegetation and small isolated trees, distributed in three

vegetation-height layers as trees dominated by P. flexuosa and G.

decorticans (average height of 3 m), shrubs dominated by T. usillo and

L. divaricata (1.5 m), and an herbaceous layer dominated by L.

crinita and P. urvilleanum (0.5 m). Heterogeneous sun exposure of

this natural topography (from 5 to 10 m in height) was evidenced in vegetation

growth. Thus, P. urvilleanum forms compact colonies and is occasionally

dominant in dry sunny áreas (fixing and stabilizing more exposed dune sectors),

whereas Z. jamesonii grows mostly in shady places, reflecting the

micro-environmental diversity of dunes and being one of the greatest floristic

resources of the study area (table 2).

Exclusive

characteristic species of this community resulted P. urvilleanum, S.

goldsackii, P. globosum, I. parodii and C. castilloniana,

preferential characteristic species are T. usillo, M. ephedroides,

L. divaricata, P. grandiflora, G. mendocina, X.

americana and T. terrestris, and accompanying species are

represented by A. lampa, L. chilense, M. aspera, B.

spinosa, S. divaricata, G. bracteata, S. leucopila, B.

barbata, S. arnottii and E. leucantha.

Species coverage

and presence spectra reflected a community dominated by nanophanerophytes

(distinctive plants in a sand dune physiognomy), therophytes and

hemicryptophytes. Microphanerophytes, although not frequent, seemed to

contribute considerable coverage in contrast to the numerous succulent

phanerophytes, of insignificant relative coverage (figure 2).

Sand dunes are generally not saline due to

soil permeability. The low water content of soil surface layers hinders organic

matter decomposition and nutrient fixing, resulting in low fertility.

Nevertheless, higher nitrogen values were found on shady sides of the dune,

closest to crops and coinciding with a higher density of P. flexuosa trees,

harbouring atmospheric nitrogen-fixing bacteria in their roots (34). Dunes pH was moderately to strongly

alkaline, consistent with higher carbonate and bicarbonate values.

Dense

scrubland of L. tenuispinosum and A. argentina with P. flexuosa

This community,

on sites with no evidence of clearing, is mainly composed of tall shrubs and

trees, isolated or in small groups (photo 2). It presented

three height layers, tres dominated by P. flexuosa (average height of 3

m), shrubs dominated by L. tenuispinosum, L. cuneifolia and A.

argentina (1.8 m), and an herbaceous layer dominated by L. crinita (0.5

m). These scrublands on saline soils occupy the greatest land expanse in the

study area, fragmented by vineyards. Tall and dense scrubland is

physiognomically predominant in the landscape, alternating with sparse

shrubland, sandy deposit sites, ground surface wáter accumulation, or evidence

of laminar runoff in natural drainage areas. This scrubland would be considered

a reference of typical natural vegetation in the area, helping understand plant

plot recovery after crop abandonment, since both communities show similar

edaphic and floristic features.

Photo 2. Overall

scrubland physiognomy.

Foto 2. Fisonomía

general del matorral.

Exclusive

characteristic species are P. tetracantha, G. boliviana and M.

ovata in Sandy soils, and A. spegazzinii in saline, finer-textured

soils. All preferential characteristic species like A. argentina, C.

genistoides, S. mirabilis and S. phleoides are typical of

saline soils. Accompanying species are P. flexuosa, A. emarginata and

T. usillo in sandy areas, and L. tenuispinosum, L. crinita,

L. cuneifolia and S. divaricata in saline or floodable lands. A.

hybridus and F. bidentis appear as accidental species after nearby

crop influence.

Scrubland

physiognomy was evidenced by dominance of nanophanerophytes, followed by

microphanerophytes. Therophytes and hemicryptophytes species were abundant. All

succulent phanerophyte species surveyed in this study are represented in this

community. Scrubland soil varied depending on the area surveyed, with sandy to

loamy textures, low fertility, on slightly to excessively saline sites. In the

latter case, the highest soluble sodium salt content (chlorides and sulfates)

indicated strongly sodic soils.

Closed

dune-base woodland of G. decorticans with L. tenuispinosum and A.

emarginata

Closed G.

decorticans woodland with three height layers included trees dominated by G.

decorticans with some P. flexuosa trees (heights from 1.5 to 5 m),

shrubs dominated by L. tenuispinosum and A. emarginata (average

height of 1 m), and an herbaceous layer with low coverage values, dominated by L.

crinita (0.80 m) and A. incarnata (0.1 m). Geoffroea decorticans woodland,

longwise developed, was found at the base of a sand dune, spreading by

gemmiferous roots, facilitating colonization of the abandoned crop area in recovery

process.

Solanum

triflorum was

found exclusive to this community, beneath P. flexuosa canopies. Preferential

characteristic species are G. decorticans, L. tenuispinosum and O.

sulphurea (tolerant to floodable, clay or saline soils); A. emarginata and

T. brunonis (representative of P. flexuosa woodland), and A.

incarnata and C. asperata (linked to sandy soils by proximity to the

sand dune of G. decorticans woodland). Accompanying species observed included

P. flexuosa, L. cuneifolia and L. chilense, notoriously

affecting total coverage and presence, where 95% of the relative cover is

contributed by nanophanerophytes and microphanerophytes, and 4% by

hemicryptophytes and therophytes. This is the only community comprising all

life forms, showing a more equitable distribution of presence values.

Soil is

sandy-loam up to 0.70 m deep, and sandy at greater depths. Fertility is low and

the sand dune base determines good water drainage, reflected in the

low-salinity soil profile.

Woodland

of P. flexuosa with A. emarginata and A. patens

Relics of P.

flexuosa woodland, fragmented by crops or cleared areas, were surveyed on

12 plots of 225 m2 each showing open P. flexuosa groves (trees between

2.5 and 5 m tall, whose canopies rarely touch), or closed and semi-closed

groves (trees up to 6.5 m tall, whose canopies frequently touch). Three height

layers were distinguished with tres dominated by P. flexuosa, sometimes

accompanied by G. decorticans and B. retama (average height of 3

m), shrubs dominated by L. tenuispinosum and/or A. emarginata (1

m), and an herbaceous layer dominated by L. crinita (0.80 m). We

observed P. flexuosa trees with a single trunk and multiple stems and

mean tree coverage ranging between 22.5% and 62.5% (value explained by the

great number of saplings with main shoot diameter under 5 cm: 130/survey, on

average).

A. patens, P.

strombulifera, A. odorata, V. astringens and V. aroma are

exclusive characteristic species in this community. P. flexuosa reaches

the highest relative coverage in the area, as well as A. mendocina and S.

aphylla, identified as preferential characteristic species. P. flexuosa canopies

prevent light from reaching the ground, limiting development of succulent

phanerophytes, geophytes and therophytes with low relative coverage values.

Soil samples

were collected from the grove adjoining the crop (A4, figure 1), finding non-saline

soils of sandy loam texture up to 0.20 m deep and sandy at greater depths. Nitrogen

and organic matter contents were among the highest recorded at all sites in the

study area and, just as phosphorus and potassium contents, reached higher

values in surface layers, probably induced by humus beneath tree canopies (34).

Low

and open steppe of L. crinita and P. flexuosa with L.

cuneifolia and B. retama in abandoned crops

Open steppe (52%

of mean total coverage) showed shrubs and grasses with young, isolated, small,

multi-stemmed trees (photo 3).

Photo 3. Physiognomy

of shrubland under recovery, colonized by grasses. Old crop furrows with

evidence of water erosion are observed.

Foto 3. Fisonomía

del arbustal en recuperación, colonizado por gramíneas. Se observan los

antiguos surcos de cultivo con evidencias de erosión hídrica.

Three height

layers were distinguished by trees dominated by P. flexuosa and B.

retama (average height of 2 m), shrubs dominated by L. cuneifolia (1

m), and an herbaceous layer of L. crinita and P. philippianum (0.80

m). This community corresponds to cleared areas levelled in 1972 for crop

establishment (grapes, apricots, alfalfa and vegetables), labored for as long

as 15 years and abandoned in 1987 due to poor performance and yield.

Agricultural tillage altered soil characteristics in this area during 25 years

between abandonment and present surveys. The surrounding natural vegetation has

recolonized this site with numerous species, typical of fine-textured, saline or

floodable soils. Adjoining crops contribute to species surviving the edaphic

limitations of these abandoned plots.

Flaveria

haumanii and

P. cuneato-ovata behave as exclusive characteristic species; L.

crinita, P. philippianum, L. cuneifolia, B. retama, S.

subulatus and D. californica as preferential characteristic species,

depending on site propensity for salt and water accumulation, or surface runoff

after rainfall (25). P. flexuosa,

as an accompanying species, contributes important coverage and presence, and C.

dactylon and P. glauca, as accidental species, denote close

crop-area influence.

Hemicryptophytes

(primarily L. crinita) establishment increases in sunny areas with

almost non-competition, defining the vegetation physiognomy together with

nanophanerophytes and microphanerophytes. Scarce succulent phanerophytes and

geophytes were evidenced by these plant limitation to propagate from seeds or

in agamic reproduction.

Soils resulted

sandy loam, with nitrogen and organic matter contents similar to non-cleared

sites. Salinity increased with depth. A gypsum layer detected in the soil

profile was analytically confirmed by higher calcium sulfate concentrations.

This pattern may be due to machinery effects during years of tillage,

generating a deep compacted layer that favoured salt concentration in the soil

profile after periodic irrigation was suspended.

In general

terms, these results are consistent with other studies associating site use

history, particularly productive plots abandonment with higher soil erodibility

and changes in landscape physiognomy of the Monte native vegetation (35, 37).

Vitis

vinifera crop

with M. albus and F. bidentis

A 31-ha vineyard

with different grapevine cultivars, conducted both vertically and horizontally

under drip irrigation, presented two height layers, one shrub layer dominated by

V. vinifera (average height of 2 m) and a herbaceous layer dominated by M.

albus, F. bidentis, S. verticillata and B. catharticus (0.5

m). The vineyard was surrounded by cleared areas with spontaneously recovered

vegetation, and by other areas with undisturbed natural vegetation, a sand

dune, and P. flexuosa groves.

Exclusive

characteristic species with higher coverage values were V. vinifera, M.

albus, B. catharticus, C. album, C. bonariensis, S.

asper and T. officinale. Overall, they were widely distributed

(normally adventitious or introduced). Despite great multiplying capacities, these

species require more water than other drought-tolerant ones, such as H. glauca,

P. glauca, C. dactylon, F. bidentis, A. hybridus, S.

verticillata, A. officinalis and S. euacanthum, all preferential

characteristic vineyard species, although capable of surviving in less

favorable conditions. L. crinita (more abundant at sunlit crop sites as

row ends, borders, plots with young vines, with less coverage or lower height)

and T. terrestris behave as accompanying species, whereas P. flexuosa

and G. decorticans are accidental, with small presence, coming from

adjoining scrublands.

Dominant in

biological spectra are nanophanerophytes (primarily grapevines, contributing

nearly half the coverage despite low presence) and therophytes (generally small

and abundant). Geophytes reach the highest coverage and frequency values,

probably because tillage does not remove rhizomes, bulbils or other organs of

asexual reproduction. Low microphanerophytes frequency is explained by spontaneous

P. flexuosa and G. decorticans individuals.

Soils are sandy

on the surface and intermediate layers and sandy -loam at depths greater than

0.5 m, with low nitrogen and organic matter contents, non to slightly saline.

Conclusions

Scrubland is the

predominant physiognomy in the area, typical for the Monte Province, with

species of the genera Larrea, Atriplex and Lycium. According

to this study, the prevailing vegetation before crop establishment was

halophilic or salt-tolerant. Species like A. lampa, A. spegazzinii,

A. argentina, P. tetracantha, G. bracteata and S.

divaricata are frequent and grow in almost all communities identified.

Prosopis

flexuosa groves

grow where trees can benefit from groundwater, bordering the steppe or in inter-dune

areas. As woodland canopy density increases, lower-height vegetation layers

tend to diminish and even disappear due to sunlight shortage, except for

sciophilous species like A. emarginata. G. decorticans is

abundant on sites with finer-textured soil, at the base of sand dunes or in

depressed areas, growing in well-defined groves. Through powerful gemmiferous

roots, this species is one main colonizer of abandoned crop fields.

In sand dunes

and their surroundings, psammophilous vegetation is well represented by a great

diversity of species, given the micro-environmental features of these

formations. P. urvilleanum is especially frequent in sand dunes

destabilized by anthropic action. Adventitious or introduced species, dependent

on adequate water supply (M. albus, C. album, S. asper, T.

officinale, etc.) coexist in combination with more rustic species able to

develop under water and/or saline stress (F. bidentis, P. glauca,

A. hybridus, H. glauca, S. verticillata, C. dactylon,

etc.). Thus, a crop area is the source of propagules dispersal for these last

species being introduced into neighbouring sites.

In shrubland

under recovery, clearing, tillage and later crop abandonment emphasized edaphic

constraints, analytically determined by signs of soil erosion, compaction or

crusting. Spontaneous re-vegetation led to lower floristic richness compared to

the adjacent natural areas taken as reference sites, after 25 years of

abandonment, with strong presence of tolerant species or species indicating

fine-textured soils, floodable areas, or with surface runoff and saline

characteristics. Original shrubland has turned into a steppe of bushes

(halophilic in part) and grasses with small young trees. Several species

present in the surroundings (O. sulphurea, S. divaricata, S.

mirabilis, C. genistoides and P. tetracantha, among others)

had difficult establishments on the plot, despite being halophilic or

salt-tolerant. This result supports the hypothesis that the main problem for

plot recovery would not be saline content, but soil structure alteration by

tillage and subsequent crop abandonment, reinforcing uncertainty about

biodiversity restoration levels to be sought in degraded soils, and recovery

time span. This study demonstrated that a survey of natural environments with

proper assessment methodologies is fundamental before land clearing for

agriculture. Determination of plant communities in fragmented areas, and

valuation of species indicative of edaphic limitations restricting crop

establishment and productivity, are essential in defining land uses.

Flora components

and species distribution are adequate indicators for monitoring environmental

processes in plant communities. Incorporating the private sector into

environmental protection systems towards the establishment of isolated

preserved sites is necessary but not sufficient in disjointed landscapes. This

first analysis of natural áreas fragmented by agriculture in Montecaseros,

shows that typical communities of the Monte subsist, demonstrating how diverse

flora is preserved in privately owned lands. Changes in floristic composition

of plant communities may have occurred in the study area during the time

elapsed between this survey and the current situation. The results obtained

constitute an important baseline for monitoring sampling sites and vegetation

dynamics in fragmented areas of Montecaseros. Cultivable land is a vulnerable

and scarce resource, particularly in drylands. A proper interpretation

recognizes limiting territory factors while approaching systemic criteria

highlighting complementarity in management between crops and native vegetation

areas. Studies of vegetation dynamism in private lands will contribute to plan

and implement sustainable land management, tending to recover and conserve

biodiversity in degraded soils, considering all associated ecosystem services.

Acknowledgements

We thank María

Margarita González Loyarte for her accurate observations and valuable review; Pablo

Molina for his generous collaboration in field work and taxonomic determinations,

and Eliana Vargas for her advice in statistic data analysis.

1. Abraham, E.

M. 2000. Geomorfología de la Provincia de Mendoza. Argentina. Recursos y

problemas ambientales de la zona árida. Provincias de Mendoza, San Juan y La Rioja.

1: 29-48.

2. Abraham, E.;

Rubio, C.; Salomón, M.; Soria, D. 2014. Desertificación: problema ambiental

complejo de las tierras secas. Ventanas sobre el territorio. Herramientas

teóricas para comprender las tierras secas. Mendoza: EDIUNC. 187-265.

3. Arana, M. D.;

Natale, E. S.; Ferretti, N. E.; Romano, G. M.; Oggero, A. J.; Martínez, G.;

Posadas, P. E.; Morrone, J. J. 2021. Esquema biogeográfico de la República

Argentina. Opera Lilloana. 56: 238.

4. Association

of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC). 2019. International, Official Methods

of Analysis, 21st ed., Gaithersburg, USA. URL: https://www.aoac.org/resources

5.

Braun-Blanquet, J. 1979. Fitosociología. Bases para el estudio de las

comunidades vegetales. H. Blume. Madrid.

6. Burkart, A.

1976. A monograph of the genus Prosopis (Leguminosae subfam. Mimosoideae).

Journal of the Arnold arboretum. 57: 219-249 and 450-525.

7. Cabrera, A.

1971. Fitogeografía de la República Argentina. Boletín de la Sociedad Argentina

de Botánica. Volumen XIV. (1-2).

8. Di Rienzo, J.

A.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M. G.; González, L.; Tablada, M.; Robledo, C. W.

2020. InfoStat, versión 2020. Centro de Transferencia InfoStat, Universidad

Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. URL: http://www.infostat.com.ar

9. Fahrig, L.

2003. Effects of habitat fragmentation on biodiversity. Annual review of

ecology, evolution, and systematics. 34(1): 487-515.

10. Flora

Argentina y del Cono Sur. Flora vascular de la República Argentina y del Cono

Sur. N.d. http://www.floraargentina.edu.ar/

11. González

Loyarte, M. M.; Gaviola, S.; Buk, E.; Rodeghiero, A. G.; Menenti, M. 2007.

Propuesta metodológica para la evaluación de tierras periféricas al oasis

irrigado de Lavalle, Mendoza (Argentina). Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 39(2): 109-126.

12. Hughes, C.

E.; Ringelberg, J. J.; Lewis, G. P.; Catalano, S. A. 2022. Disintegration of

the genus Prosopis L. (Leguminosae, Caesalpinioideae,

mimosoid clade). PhytoKeys. 205: 147-189. https://doi.org/10.3897/phytokeys.205.75379

13. Instituto

Geográfico Nacional (IGN). N.d. Información geoespacial. Accessed 02.05.22.

https://www.ign.gob.ar/

14. Instituto

Nacional de Estadística y Censos (INDEC). 2021. Censo Nacional Agropecuario

2018: resultados definitivos. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires.

15. IPNI. 2023.

International Plant Names Index. Published on the Internet http://www.ipni.org, The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Harvard

University Herbaria & Libraries and Australian National Herbarium.

16. Ministerio

de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible de la Nación (MAyDS). 2020. República

Argentina. Reporte final sobre el Programa de Establecimiento de Metas

Voluntarias de Neutralidad de la Degradación de la Tierra. Ciudad de Buenos

Aires. https://www.argentina.gob. ar/ambiente/contenidos/faros-de-conservacion

17. Norte, F.

2000. Mapa climático de Mendoza. Argentina. Recursos y Problemas Ambientales de

la Zona Árida. Primera Parte. Provincias de Mendoza, San Juan y La Rioja. 1:

25-27.

18. Pérez

Valenzuela, B. R. 1999. Edafología en la agricultura regadía cuyana. Fundar.

205 p.

19. Pérez

Valenzuela, B. R.; Salcedo, C. E.; De Cara, D. E.; Capuccino, S. N. 2001.

Vegetación de San Martín (Mendoza). Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias .

Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 33(2): 63-71.

20. QGIS

Development Team. 2022. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source

Geospatial Foundation Project. https://qgis.org/es/site/

21. Quijas, S.;

Schmid, B.; Balvanera, P. 2010. Plant diversity enhances provision of ecosystem

services: A new synthesis. Basic and Applied Ecology. 11(7): 582-593.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2010.06.009

22. Raunkiaer,

C. 1934. Life forms and terrestrial plant geography. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

23. Regairaz, M.

C. 2000. Suelos de Mendoza. Argentina. Recurso y problemas ambientales de la

zona árida. Provincia de Mendoza, San Juan y La Rioja. 1: 59-62.

24. Roig, F. A.

1973. El cuadro fitosociológico en el estudio de la vegetación. Deserta. 4:

45-67.

25. Roig, F. A.

1981. Flora de la reserva ecológica de Ñacuñán. Cuaderno Técnico IADIZA. 3(80):

5-176.

26. Roig, F. A.;

Roig-Juñent, S.; Corbalán, V. 2009. Biogeography of the Monte desert. Journal

of Arid Environments. 73(2): 164-172.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2008.07.016

27. Salvia, R.;

Quaranta, V.; Sateriano, A.; Quaranta, G. 2022. Land Resource Depletion,

Regional Disparities, and the Claim for a Renewed ‘Sustainability Thinking’

under Early Desertification Conditions. Resources. 11(3): 28.

https://doi.org/10.3390/resources11030028

28. Smiraglia,

D.; Tombolini, I.; Canfora, L.; Bajocco, S.; Perini, L.; Salvati, L. 2019. The

latent relationship between soil vulnerability to degradation and land

fragmentation: A statistical analysis of landscape metrics in Italy, 1960-2010.

Environmental management. 64(2): 154-165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-019-01175-6

29. Swinton, S.

M.; Lupi, F.; Robertson, G. P.; Hamilton, S. K. 2007. Ecosystem services and

agriculture: cultivating agricultural ecosystems for diverse benefits. Ecological

economics. 64(2): 245-252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.09.020

30.

Tropicos.org. Missouri Botanical Garden. https://tropicos.org

31. Turland, N.

J.; Wiersema, J. H.; Barrie, F. R.; Greuter, W.; Hawksworth, D. L.; Herendeen,

P. S.; Knapp, S.; Kusber, W.-H.; Li, D.-Z.; Marhold, K.; May, T. W.; McNeill,

J.; Monro, A. M.; Prado, J.; Price, M. J.; Smith, G. F. (eds.) 2018.

International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen Code)

adopted by the Nineteenth International Botanical Congress Shenzhen, China,

July 2017. Regnum Vegetabile 159. Glashütten: Koeltz Botanical Books. DOI

https://doi.org/10.12705/Code.2018

32. United

States Department of Agriculture (USDA). 1954. Diagnosis and improvement of

saline and alkali soils. Agriculture Handbook 60, Richards, L.A. (Ed.). U. S.

Laboratory Staff, Washington, DC.

33. Viglizzo, E.

F.; Frank, F. C.; Carreño, L. V.; Jobbágy, E. G.; Pereyra, H.; Clatt, J.;

Pincen, D.; Ricard, M. F. 2011. Ecological and environmental footprint of 50 years

of agricultural expansion in Argentina. Global change biology, 17(2): 959-973. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02293.x

34. Villagra, P.

E. 2000. Aspectos ecológicos de los algarrobales argentinos. Multequina. 9(2):

35-51.

35. Villagra, P.

E.; Defossé, G. E.; Del Valle, H. F.; Tabeni, S.; Rostagno, M.; Cesca, E.;

Abraham, E. 2009. Land use and disturbance effects on the dynamics of natural

ecosystems of the Monte Desert: Implications for their management. Journal of

Arid Environments. 73(2): 202-211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2008.08.002

36. Villagra, P.

E.; Álvarez, J. A. 2019. Determinantes ambientales y desafíos para el

ordenamiento forestal sustentable en los algarrobales del Monte, Argentina.

Ecología Austral. 29(1): 146-155. https://doi.org/10.25260/EA.19.29.1.0.752

37. Yannelli, F.

A.; Tabeni, S.; Mastrantonio, L. E.; Vezzani, N. 2014. Assessing degradation of

abandoned farmlands for conservation of the Monte Desert biome in Argentina.

Environmental management. 53(1): 231-239.

38. Zuloaga, F.;

Morrone, O. 1999. Catálogo de las Plantas Vasculares de la República Argentina.

II. Monogr. Syst. Bot. Missouri Bot. Gard. 74.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ST-hgPbnmvltbARGf2o7KkoD0IXoNFGP/view?usp=sharing