Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 55(2). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2023.

Original article

Cover

crops in pear (Pyrus communis) orchards: effects on soil nematode

assemblage

Cultivos

de cobertura en huertos de peras (Pyrus communis): efectos sobre el

ensamble de nematodos del suelo

Claudia Viviana

Azpilicueta1, 2*,

María Cristina

Aruani3,

Pablo Reeb3

1Ministerio

de Producción e Industria. Laboratorio de Servicios Agrarios y Forestales.

Santiago del Estero 426 C. P. 8300. Neuquén. Argentina.

2Universidad

Nacional de Río Negro. Estados Unidos 750. General Roca. C. P. 8332. Río Negro.

Argentina.

3Universidad

Nacional del Comahue (UNCo). Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Ruta 151. Km 12,5.

Cinco Saltos. C. P. 8303. Río Negro. Argentina.

*azpilore50@hotmail.com

Abstract

Long-term

vegetation cover can affect soil organic carbon content and carbon flow within

the soil food web. Nematode trophic structure and soil properties were

evaluated in pear rows (intra) maintained without weeds applying herbicide and

in the inter-rows (between rows) covered with: Medicago+grasses (MG),

fescue or spontaneous vegetation. Soil samples were taken at 0-20 and 20-40 cm

depths from 2012 to 2014. Nematode assemblage was different in each inter-row

and row, mainly in the topsoil. The inter-rows were reservoirs of

omnivores-predators. The MG inter-row promoted the highest accumulation of

organic carbon, total N and exchangeable K in the soil. The enrichment index

was related to the quantity of dry matter produced by cover crops with the

highest index observed in MG. Nematode biomass showed a positive correlation

with intra and inter-rows soil organic carbon. Carbon flow through bacterivores

prevailed in intra-rows, while bacterivores or herbivores canalized the

inter-rows.

Keywords: nematode trophic

groups, soil food web, metabolic footprint, soil physicochemical properties,

pear tree

Resumen

Las coberturas

vegetales a largo plazo pueden afectar el contenido de carbono del suelo y el

flujo de carbono en la red trófica del suelo. Se evaluó la estructura trófica

de nematodos y propiedades del suelo en las filas de pera mantenidas sin

malezas por aplicación de herbicidas y en los interfilares (entre filas)

cubiertos con: Medicago+gramíneas (MG), festuca o vegetación espontánea.

Las muestras de suelo fueron extraídas a 0-20 cm y 20-40 cm de profundidad

durante 2012 a 2014. El ensamble de nematodos fue diferente en cada interfilar

y fila, principalmente en el horizonte superficial. Los interfilares fueron

reservorios de nematodos omnivoros-predators. El interfilar con MG promovió la

mayor acumulación de materia orgánica, N total y potasio intercambiable en el

suelo. El índice de enriquecimiento estuvo relacionado con la cantidad de

materia seca producida por las coberturas, y los valores más altos del índice

se observaron en MG. La biomasa de nematodos se correlacionó positivamente con

el contenido de carbón orgánico del suelo en las filas e interfilares. El flujo

de carbono fue canalizado por los nematodos bacteriófagos en las filas y a

través de los bacteriófagos o herbívoros en los interfilares.

Palabras clave: grupos tróficos

de nematodos, red trófica del suelo, huella metabólica, propiedades

físico-químicas del suelo, peral

Originales: Recepción: 03/11/2022 - Aceptación: 31/07/2023

Introduction

Soil organic

matter contributes to physical, chemical and biological fertility of soil. Some

practices such as reduced tillage, direct seeding, and cover crops help

preserve the organic carbon content in soil. Cover crops in between rows

(inter-row) of fruit plantations improve physical and chemical properties of

soil (2, 35). In semiarid climate, the

practice also prevents fruits from becoming sunburnt (26). In the Argentina provinces of Rio Negro and Neuquén,

plant species such as Festuca arundinacea, F. rubra, Trifolium

pratense, T. repens, Lolium perenne and Vicia sativa are

the most common cover crops used by growers (35).

However, some farmers maintain their inter-row with spontaneous vegetation or

bare soil.

Vegetation cover

returns carbon to the soil from above-and below-ground biomass. Root-derived

carbon has a longer residence time in soil than carbon derived from above-ground

biomass (28). Roots contribute to a more

stable carbon source (20) and increase

soil carbon sequestration, which is an important aspect of sustainable farming system.

Plant functional type regulates the vertical distribution of soil organic carbón

(19). Root system morphology controls the

availability of soil organic carbon and phosphorus (31,

39) and the vertical distribution of nematodes in the soil (33). Soil fauna depends on carbon resources

through the complex interactions between the roots and microorganisms (5). Microbivore nematode biomass is correlated

with levels of soil carbón (41) and

nematodes have also been shown to increase microbial turnover and soil N and P availability,

increasing plant biomass production (16).

The type of plant species present in the community, rather than the diversity

of the community itself, can produce multitrophic effects on the soil food web

(37). Winter cover crops, such as Hordeum

vulgare and Pisum sativum, as well as Fabaceae species have been

shown to increase soil food web complexity (9, 21).

Both the use of cover crops and the incorporation of crop straw have been shown

to enhance nematodes biomass, thus facilitating carbon flow into the soil food

web (41).

Previous studies

on fruit orchards have focused on how the introduction of cover crops affects

the nematode assemblage in different crops such as apple (30), vineyards (27),

and banana (9). However, relatively

little study has been conducted on soil carbon content and nematode assemblages

in vegetation-covered inter-rows and vegetation-free tree rows maintained with

herbicide. The present study contributes to current the understanding of how

using of different long-term vegetation covers in the inter-rows of pear

orchards can affect carbon flow within soil food webs. The objectives of this

study were to 1) describe the relationships between nematode assemblages and

the edaphic properties of the soil profile; 2) assess soil food web conditions

and 3) determine the magnitude of the metabolic footprints of nematode trophic

groups in a pear orchard.

Materials

and Methods

Description

of the study area and soil sampling

The study was

conducted in a commercial pear orchard (38°51’15.7” S, 68°02’46.8” W) in the

province of Río Negro, Argentina. The region has a mild continental and arid

climate. The moisture regime is aridic and the temperature regime is thermic.

The average temperature of the warmest month (January) is 21.9°C while the

coldest month (July) averages 5.7°C. The annual average precipitation is 224

mm. Soil belongs to the Aridisol orden and is classified as Typic Acuicambid (34) with a clay loam texture at 0-20 cm (about

80% silt + clay) and silty clay loam at 20-40 cm depth.

The study was

conducted in an 18-year-old pear orchard (Pyrus communis L.cv

Williams) where tree spacing was 4 x 2 m (1200 pear tree ha-1). Inter-rows (i)

and rows (r) in three plots were studied. The inter-row of each plot was

maintained with different vegetation cover: 1) Medicago sativa L. plus

grasses; (MG), 2) Festuca arundinacea; (FE), and 3) spontaneous

vegetation; (SV). The pear rows were maintained without weeds with the

application of herbicide. Soil samples from six treatments (MGr, SVr, FEr, MGi,

SVi, FEi) and five replicates (sites) were randomly collected to assess soil

properties and nematode assemblages at 0-20 and 20-40 cm depth. Each treatment

was identified according to the inter-row cover of each plot. Composite soil

samples of eight random sub-samples per each combination of treatment by site

(n=30) and depth were collected with a soil auger (2.5 cm diameter). In each

row, soil samples were taken from an area of 1 x 3 m under a selected pear tree

(0.50 m and 1.50 m on both sides of a pear tree, both transversely and

longitudinally to the tree rows, respectively). In each inter-row, soil samples

were taken from an area similar to the row at a distance of about 1.50 m from

the trunk of the selected tree from each row. Soil samples were taken in spring

and autumn, from November 2012 to December 2014. The sampling dates for the FE

and SV plots were as follows: the 9th of November 2012, the 30th of April and

the 12th of November 2013, and the 23rd of April and the 18th of November 2014.

The MG plot was sampled on the following dates: the 22nd of November 2012, the

20th of May and the 11th of December 2013, and the 28th of May and the 1st of

December 2014.

Each plot was

irrigated by flooding. Inter-row soil with MG (MGi) was seeded in 2004 with

alfalfa (40kg ha-1) and fescue (40kg ha-1). Throughout the study, the inter-row

soil was covered by 30% alfalfa, 40% Cynodon dactylon and 30% F.

arundinacea plus Plantago lanceolata. Fescue inter-row (FEi) was

seeded in 2005. At the time of the study, the vegetation cover of the FEi was

fescue and 10% Cynodon dactylon. Plant species composition in the SV

inter-row (SVi) was 45% C. dactylon and 21% Trifolium repens. Of

the remaining plants (34%), a mix of Taraxacum officinale, Trifolium

pratense, Cichorium intybus, P. lanceolata, Lactuca serriola, Polygonum

aviculare and Sonchus oleraceus were recorded. The inter-row was

seeded to a width of 3 m starting at 0.50 m from the trunk of each pear tree.

Vegetation cover was mowed three or four times during summer (2012-13,

2013-14), and the clippings were left on the soil surface to decompose. Part of

the above-ground plant biomass was collected in a 1 x 1 m quadrant in the

inter-row space of each treatment. Shoots and leaves were dried in an oven at

60°C to a constant weight to determine dry matter production. Tree rows were

managed according to the traditional practices employed by growers in this

region. In each growing season, trees were fertilized in spring at 100 units of

nitrogen per hectare, half in October-November and half in December. In autumn,

fertilization was completed with 15 units of nitrogen per hectare. Fertilizers

were applied in the tree rows, including ammonium sulfate, solMIX, phosphoric acid

and diammonium phosphate. Herbicides were used to achieve weed control. For

each growing season, 1,1’-dimethyl-4-4’-bipyridinium dichloride was applied 2-3

times at a rate of 3.5 L ha-1 in spring and glyphosate was applied 4-5 times in

summer at a rate of 4 L ha-1.

Soil

physicochemical and nematode analyses

Soil organic

carbon (SOC) was determined by wet oxidation (K2Cr2O7). Soil salinity was

measured from the extracted saturation and expressed as electrical conductivity

(EC). Sodicity was expressed as exchangeable sodium percentage (ESP).

Exchangeable potassium (K) and sodium were measured with a flame spectrometer

after exchange with ammonium acetate. Available phosphorus (P) in soil was

determined by the Olsen method. Total nitrogen was measured using the Kjeldahl

method only at the first time of sampling at 0-20 cm depth.

Soil nematodes

were extracted from 100 g of fresh soil using centrifugal-flotation (6). Soil moisture was determined gravimetrically

by drying the samples at 105°C for 24 h. Nematode counts for each taxon were

adjusted to the number of nematodes per 100 g of dry soil. The recovered

nematodes were counted and preserved in formalin. At least 100 specimens from

each sample were randomly selected and identified to genus or family level to

be assigned to five trophic groups: bacterivores, fungivores, obligate plant

feeders, facultative plant feeders, and omnivores-predators according to Yeates et al. (1993). The abundance of nematode

trophic groups and the trophic diversity index (T = 1/Σpi 2, pi is the

proportion of the trophic group i in nematode assemblage) were

calculated to describe the nematode assemblage. The enrichment index (EI),

structure index (SI) and, channel index (CI) were calculated to assess the

condition of the soil food web according to Ferris et

al. (2001). Nematode biomass and metabolic footprints were calculated

using NINJA´s on-line web application (32).

Metabolic footprint informs on the ecological function undertaken by nematodes

(14).

Statistical

analyses

Analysis of

variance of a linear mixed model was employed to compare the fixed effects of

treatment and season on soil physicochemical data, nematode abundance,

ecological indices, and metabolic footprints using the statistical software Infostat

(2020). Each soil depth was investigated separately. A random effect was

included to model the variability of sites within the plots. Differences

obtained at the p < 0.05 level were considered significant using the

LSD Fisher test. An analysis of variance was performed to test for differences

in dry matter production per cover. Principal component analysis (PCA) was

performed to explore the relationship between nematode trophic groups and soil

physicochemical properties under different treatments and depths. A Pearson’s

correlation analysis was performed to quantify the association between SOC and

biomass of nematode assemblage in the row and the inter-row in the 0-40 cm soil

profile using Infostat (2020).

Results

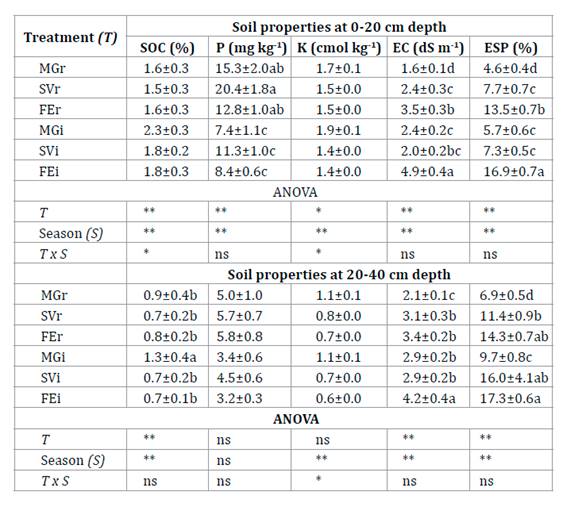

Soil

physicochemical properties and plant dry matter production

At 0-20 cm

depth, SOC was higher in MGi in spring than in other treatment x season

interactions (table 1). In spring and autumn, SOC was higher

in MGi than in MGr. The value of total N in MGi was 0.15% and higher than the

other treatments (p<0.01). Available P was higher in the rows and SVi than

in FEi and MGi. Exchangeable K was higher in MGi in spring than in other

treatment x season interactions. The highest values of EC and ESP were obtained

in FEi, and were greater in autumn than in spring. At 20-40 cm depth, SOC was

greater in MGi than under all other treatments which did not vary from each

other. The average EC value was higher in FEi (table 1).

Table

1. Main values of soil properties (±SE) in

six treatments at two depths.

Tabla 1. Valores

medios de las propiedades del suelo (±ES) en seis tratamientos a dos

profundidades.

Each treatment was identified according to the

inter-row cover of each plot: Medicago+grasses; MG, spontaneous

vegetation; SV and fescue; FE. r: row and i:

inter-row. SOC: Soil organic carbon, K: Exchangeable potassium, P: Available

phosphorus, EC: Electrical conductivity and ESP: exchangeable sodium

percentage. Different letters in the column indicate significant differences

between treatments for analysis of variance at * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, and

ns: not significant according to Fisher test.

Cada tratamiento fue identificado de acuerdo con la

cobertura del interfilar de cada parcela Medicago+grasses; MG,

vegetación espontánea; SV y festuca FE. r: fila e i:

interfilar. SOC: Carbono orgánico del suelo, K: Potasio intercambiable, P:

Fósforo disponible, EC: conductividad eléctrica, y ESP: porcentaje de sodio

intercambiable. Diferentes letras en la columna indican diferencias

significativas entre tratamientos para el análisis de varianza a * P<0,05,

** P<0,01, y ns: no significativo según la prueba de Fisher.

Plant dry matter

production was higher in the MGi than in other soil covers (p<0.01). The

amount of dry biomass was 14.3, 8.1 y 6.5 t ha-1 for the MG, FE and SV

inter-rows, respectively.

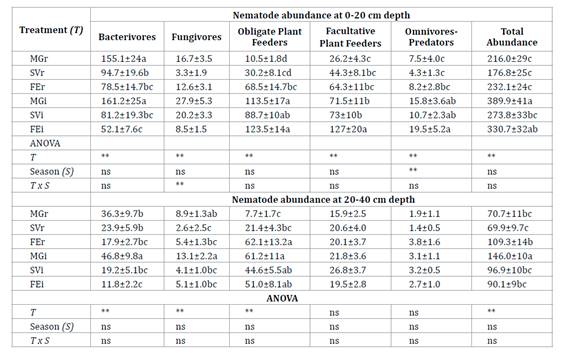

Nematode

abundance

Total nematode

abundance was higher in each inter-row than in its associated row (table

2). At 0-20 cm, bacterivores were most abundant in the rows, whereas

different trophic groups predominated in abundance in the inter-rows. The 20-40

cm layer was generally dominated by obligate plant feeders, followed by

bacterivores.

Table

2. Mean abundance of nematode (individuals

100g-1 dry soil ±SE) in six treatments at two depths.

Tabla 2. Abundancia

media de nematodos (individuos en 100g-1 de suelo seco ±ES) en seis

tratamientos a dos profundidades.

Each treatment was identified according to the

inter-row cover of each plot: Medicago+grasses; MG, spontaneous

vegetation; SV and fescue; FE. r: row and i:

inter-row. Different letters in the column indicate significant differences

between treatments. Significance levels: *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ns: not

significant according to Fisher test.

Cada tratamiento fue identificado de acuerdo con la

cobertura del interfilar de cada parcela Medicago+grasses; MG,

vegetación espontánea; SV y festuca FE. r: fila e i:

interfilar. Diferentes letras en la columna indican diferencias significativas

entre tratamientos. Niveles de significancia: *P<0,05, **P<0,01, y ns: no

significativo según la prueba de Fisher.

At 0-20 cm depth

the abundance of bacterivores was higher in MGi and MGr than in other

treatments (table 2). The abundance of fungivores was higher

in MGi and SVi. The population density of obligate plant feeders did not vary

between MG, SV and FE inter-rows. The highest density of facultative plant

feeders was observed in FEi and was higher in each inter-row than its

associated row. The population density of omnivore-predators was greater in the

inter-rows than in the rows, and greater in spring than in autumn. The

abundance of bacterivores at 20-40 cm depth showed a similar trend as at 0-20

cm depth (table 2). The abundance of fungivores was higher in

MGi and MGr. Obligate plant feeders were more abundant in the inter-rows and

FEr.

Linking

the nematode assemblage with soil physicochemical properties

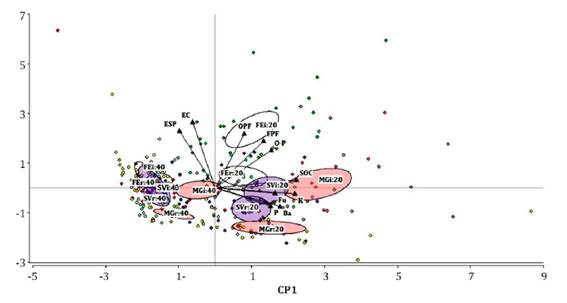

An exploratory

PCA showed the relationships between the nematode assemblage and soil

properties in different treatments and soil profiles (figure 1).

Confidence ellipses around each treatment are shown:

MGr20 and MGi20: row and inter-row of plot with Medicago+grasses cover at

0-20 cm. SVr20 and SVi20: row and inter-row of plot with spontaneous vegetation

cover at 0-20 cm. FEr and FEi: row and inter-row of plot with fescue cover at

0-20 cm. The same references are repeated to 20-40 cm depth. SOC: Soil organic

carbon, K: Exchangeable potassium, P: Available phosphorus, EC: Electrical

conductivity, ESP: exchangeable sodium percentage, Ba: Bacterivores, Fu:

Fungivores, OPF: Obligate plant feeders, FPF: Facultative plant feeders, and

O-P: Omnivores-Predators.

Las elipses de confianza se observan por cada

tratamiento: MGr and MGi: fila e interfilar de la parcela con la cobertura Medicago+grasses

a los 0-20 cm. SVr and SVi: fila e interfilar de la parcela con vegetación

espontánea a los 0-20 cm. FEr and FEi: fila e interfilar de la parcela con la

cobertura festuca a los 0-20 cm. Las mismas referencias se repiten para 0-40

cm. SOC: Carbono orgánico del suelo, K: Potasio intercambiable, P: Fósforo

disponible, EC: Conductividad eléctrica, ESP: Porcentaje de sodio

intercambiable, Ba: Bacteriófagos, Fu: Fungívoros, OPF: Fitófagos obligados,

FPF: Fitófagos facultativos y O-P: Omnívoros-Predatores.

Figure 1. Biplot

of principal component analysis based on the soil properties and nematode

trophic groups at two depths.

Figura 1. Gráfico

del análisis de componentes principales sobre las propiedades del suelo y los

grupos tróficos de nematodos a dos profundidades.

The first two

principal components, PC1 (36.4%) and PC2 (17.1%), explained 53.5% of the

variance. PC1 was strongly and positively correlated with SOC, K, and the

abundance of bacterivores and fungivores. PC2 was positively correlated with

the abundance of obligate plant feeders, EC and ESP. A grouping pattern

according to soil depth can be observed along the PC1 axis. The nematode assemblage

was generally different among treatments at 0-20 cm depth. In contrast, at

20-40 cm, a clustering pattern between FE and SV inter-rows and rows was

observed.

Nematode

community indices, biomass and metabolic footprints of soil nematodes

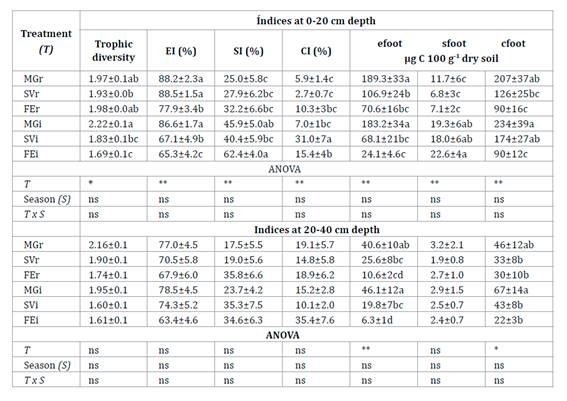

At 0-20 cm

depth, EI was higher in MGr and MGi (table 3). In general, SI

was higher in each inter-row compared to its row. CI was higher in SVi than in

the other inter-rows. At 20-40 cm depth the values of EI, SI, and CI did not

vary between treatment and season (table 3).

Table 3. Mean

values of nematode indices (±SE) in six treatments at two depths.

Tabla 3. Valores

promedio de los índices de nematodes (±ES) en seis tratamientos a dos

profundidades.

Each treatment was identified according to the

inter-row cover of each plot: Medicago+grasses; MG, spontaneous

vegetation; SV and fescue; FE. r: row and i:

inter-row. EI: enrichment index, SI: Structure index. CI: Channel index, efoot:

enrichment footprint, sfoot: structure footprint, and cfoot: composite

footprint. Different letters in columns indicate significant differences

between treatments. Significance levels: *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ns: not

significant according to Fisher test.

Cada tratamiento fue identificado de acuerdo con la

cobertura del interfilar de cada parcela Medicago+grasses; MG,

vegetación espontánea; SV y festuca FE. r: fila e i:

interfilar. EI: Índice de enriquecimiento, SI: Índice de estructura, CI: Índice

canal, efoot: huella de enriquecimiento, sfoot: huella de estructura, y cfoot:

huella compuesta. Diferentes letras en las columnas indican diferencias

significativas entre tratamientos. Niveles de significancia: *P<0,05,

**P<0,01, y ns: no significativo según la prueba de Fisher.

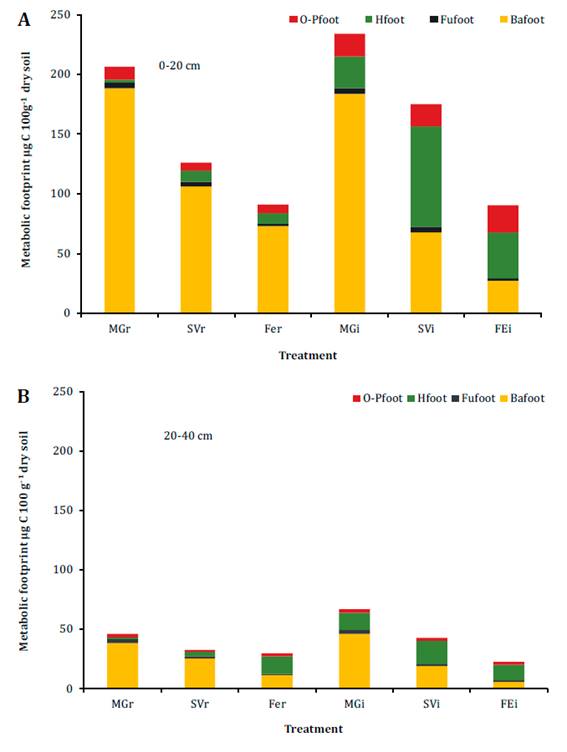

In the 0-40 cm

soil profile, the biomass of nematode assemblage showed a positive correlation

with the content of SOC in the row (r=0.48, p<0.01) and in the inter-row

(r=0.46, p<0.01). At 0-20 cm depth, nematode composite footprint was higher

in MGi and SVi than FEi (table 3). Bacterivores accounted for

the highest metabolic footprint in the rows, while bacterivores and herbivores

were prominent in the inter-rows (figure 2a).

Each treatment was identified according to the

inter-row cover of each plot: Medicago+grasses; MG, spontaneous

vegetation; SV and fescue; FE. r: row and i:

inter-row. Ba: Bacterivores, Fu: Fungivores, H: Herbivores, and O-P: Omnivores-

Predators.

Cada tratamiento fue identificado de acuerdo con la

cobertura del interfilar de cada parcela: Medicago+grasses; MG,

vegetación espontánea; SV y festuca FE. r: fila e i:

interfilar. Ba: Bacteriófagos, Fu: Fungivoros, H: Herbívoros, y O-P:

Omnívorospredatores.

Figure 2. Metabolic

footprint (foot) of nematode trophic groups in six treatments at (A) 0-20 and

(B) 20-40 cm depths.

Figura 2. Huella

metabólica (foot) de los grupos tróficos de nematodos en seis tratamientos a

las profundidades (A) 0-20 y (B) 20-40 cm.

Bacterivore

footprint was higher in MGi and MGr than in the other treatments (p<0.01).

Herbivore footprint was highest in SVi (p<0.01, figure 2a)

and was greater in the inter-rows than in the rows (p<0.01). MGi and MGr

were associated with a higher enrichment footprint (table 3).

Structure footprint was higher in the inter-row tan in its associated row. At

20-40 cm depth, composite footprint was higher in MGi than in the other

inter-rows, while it was similar among rows (table 3).

Herbivore footprint did not vary among inter-rows (p<0.03, figure

2b). MGi and MGr were associated with a higher enrichment footprint (table 3).

Discussion

Soil

physicochemical properties and nematode assemblages at different soil depths

Vegetation cover

significantly impacted soil organic carbon levels in the studied pear orchard. Medicago+grasses-covered

inter-rows exhibited SOC levels that were 22% and 46% higher at depths of 0-20

and 20-40 cm, respectively, than other covers at those depths. SOC provides

resources for soil biota (31, 41) and

this may be reflected by the positive association seen between soil carbon and

nematode biomass in the soil profile. Stratification of SOC is common in

agroecosystems (17). In MGi, the

stratification of SOC was less noticeable than in the SV and FE inter-rows.

Plant functional types and architectural root characteristics regulate the

vertical distribution of soil organic matter (19).

Vegetal species such as Medicago sativa, which has a vigorous root

system in deep soil, contribute to carbon storage in the soil profile because

the carbon produced by roots forms stable organo-mineral associations (20). In the present study, maintaining a

permanent cover with MGi in springtime resulted in a higher level of SOC in the

soil profile compared to MGr. Interestingly, this increase in organic matter

-evidently brought about by MG cover- coincided with the period when new pear

roots are developed, thus ensuring that nutrients are available for fruit crop

uptake.

Total nematode

abundance showed a differential distribution between the soil layers; about 75%

of all nematodes recorded at 0-40 cm depth were recovered from the top 0-20 cm.

This differential distribution pattern applies to both inter-rows and rows

alike. Previous studies have shown a similar trend (31,

39). Total nematode abundance was generally greater in inter-rows

than in rows at a depth of 0-20 cm (table 2). In the

inter-row of each plot, populations of fungivores, facultative and obligate

plant feeders, and omnivores-predators were seen in greater abundance than in

the row. Using herbicides to control weeds in the pear row could alter the

nematode assemblage. Seedling emergence and root length were reduced by

application glyphosate on pre-existing vegetation (29).

The loss of plants due to weeding may result in a loss of food resources,

thereby affecting several trophic groups (25).

Environmental

and edaphic factors shape spatial heterogeneity of soil according to land use

and root distribution (24). Nematode

assemblages will therefore differ depending on resource availability and soil

spatial heterogeneity along the depth gradient (13).

In the topsoil, each inter-row recorded different nematode assemblages that

were associated with particular edaphic properties. In MGi, bacterivore

nematodes dominated in a non-saline soil with the highest content of SOC, total

N and exchangeable K, which is in line with other studies in Fabaceae crops (9, 37). Bacterivores are attracted by the

volatile compounds released by legume roots, which lead to the spread of

bacteria and improve rhizobial inoculation (18).

In the present study, total soil N supply was 30% higher under Medicago+grasses

cover tan any other cover. Nearby trees can capture this inter-row nitrogen.

The pear tree develops roots with a greater exploratory capacity when grafted

on rootstock, and these roots exceed the canopy´s projection on the ground,

this allows the plant to capture the available nitrogen in the inter-row. In

SVi, obligate plant feeders and bacterivores were similar in abundance and were

the most abundant groups. The highest plant species richness and available P

content in non-saline soil were associated with nematode assemblages´ trophic

structure. Floristic diversity has a potential role in soil P input due to a

differential accumulation of P in each plant (23), which contributes

to an increasing this nutrient of limited mobility in the soil profile. In the

present study, P was probably released by the decomposition of plant residues

from vegetation that was mown over the summer. Furthermore, frosts in Winter

and spring are common in the study region and cause the death of shoot and root

cells, releasing intracellular P (22). In

FEi, obligate and facultative plant feeders were found to be the most abundant

groups in slightly saline and sodic soil. The index of nematode trophic diversity

recorded its lowest value in this treatment compared to other treatments. This

finding concurs with Su et al. (2016), who

found a sensitivity of this nematode trophic group to slightly saline soils.

For a detailed view of the composition of soil nematode plant feeders see Azpilicueta et al. (2017).

In the

sub-superficial soil, in the inter-rows of SV and FE, obligate plant feeders

dominated, while in the pear rows, plant feeders and bacterivores prevailed in

saline and sodic soil. A previous study on a pear orchard observed that plant

feeders were the most abundant trophic group in saline and slightly sodic soil

(3). In the valleys of Río Negro and

Neuquén, about 40% of soils from fruit orchards have a shallow water table,

which impacts the salinization process of soil (15)

because the water table fluctuates to different depths during the crop growing

season (1).

Soil

food web condition

In the topsoil,

the higher enrichment index (EI) found in the MGi suggests a more enriched

condition of the soil food web than in the SV and FE inter-rows. A positive

relationship between EI and quantity of cover crop biomass was found by Dupont et al. (2009). In the present study,

plant dry matter production was ca. two times

higher in the MGi than in the other inter-rows. The return of plant residues to

the soil contributes to the availability of basal resources for primary

decomposers in the soil food web (38).

This was reflected in the fact that the highest bacterivore and fungivore

abundance observed in our study was recorded in MGi. These trophic feeding

groups have shown to be first responders to resource enrichment (41).

Microbivore

nematodes are at the base of the soil food web and drive energy flow to the

higher trophic groups into the bacterial or fungal energy channel. The channel

index values were less than 30% in the inter-rows and rows, indicating that the

bacterial channel was dominant compared to the fungal channel (12). The magnitude of soil energy channels can be

estimated using both biomass and metabolic footprint attributes (7, 14). The bacterivore metabolic footprint was

higher in MGi than in SVi and FEi in the soil profile. Furthermore, the

bacterivore footprint represented 70% of the composite footprint, indicating

that the highest carbon assimilation in the soil food web occurred through

bacterial channels. Another soil energy channel is mediated by plant feeding

and involves live roots. Herbivore footprints were higher in the inter-rows

than in the rows, particularly in SVi, which could reflect the heterogeneity of

resources due to greater vegetation diversity. Plant species identity has

relevance in controlling energy channels in soil systems (7).

Structure index

and footprint were low to moderate across all treatments; consequently, the

magnitude of pest suppression performed by omnivores-predators was low. Due to

the high content of fine particles, the movement and reproduction of

omnivores-predators could be affected by granulometric soil composition. In

addition, the predominance of small pores could reduce the abundance of the

largest nematodes in the soil profile (33).

Even so, SI and sfoot were higher in the inter-rows than in the rows,

suggesting a more complex nematode assemblage with more linkages in the food

web in the inter-rows. The inter-rows with vegetation covers were reservoirs of

omnivores-predators, which can regulate lower soil food web levels, including

plant-feeders. The structure footprint was lower than the enrichment footprint

in both rows and inter-rows. According to Ewald et al.

(2020), food webs in arable systems have low productivity and high resource

input. The mineralization service given by the enrichment footprint was higher

in MGi and MGr. The excretory products of nematodes, such as amino acids, NH4 +

and PO4 -3 increase soil nutrient availability (16),

and they may improve the growth and production of fruit and cover crops.

Conclusions

This study has

enhanced the current knowledge of carbon flow in the soil food web in the

inter-rows and rows of a pear orchard. Bacterial channels prevailed in the

rows, while different energy channels were found in the inter-rows. The

relative magnitude of soil energy channels revealed higher carbon flow within

the soil food web under Medicago+grasses and spontaneous vegetation than

under fescue. The herbivore energy channel made a significant contribution

under spontaneous vegetation.

Our data suggest

that nutrient mineralization was greater in inter-rows and rows in the Medicago+grasses

plot. Moreover, a higher soil carbon content was seen in the inter-row under Medicago+grasses,

and this treatment also yielded a higher abundance of bacterivores and fungivores

in the soil profile, and was thus seen to have an impact on soil fertility.

Each cover crop

was associated with a different nematode assemblage due to their particular

edaphic properties, mainly in the topsoil. Nematode biomass was positively

correlated with soil carbon content. The abundance of omnivores-predators

associated with the structure of soil food web was greater in the inter-rows

than in the rows. Consequently, pear rows with disturbed soil food webs could

be improved with the assistance of nematodes from associated inter-rows. Taken

together, these findings suggest that adequate soil management in inter-rows

may promote the abundance of beneficial nematodes and improve the productive

capacity of pear trees.

1. Apcarian, A.;

Schmid, P.; Aruani, M. 2014. Suelos con acumulaciones calcáreas y yesíferas en

el Alto Valle de Río Negro. Patagonia Norte. En: Imbelone, P. (Ed.). Suelos con

acumulaciones calcáreas y yesíferas en Argentina. Buenos Aires. Argentina.

INTA. 149-182.

2. Aruani, M.;

Sánchez, E.; Reeb, P. 2006. Cambios en las propiedades de un suelo franco bajo

producción orgánica de manzano utilizando coberturas vegetales. Revista

Argentina de la Ciencia del Suelo 24: 131-137.

3. Aruani, M.;

Azpilicueta, C.; Reeb, P.; Arias, M. 2017. Ensamble de nematodos en una

cronosecuencia en suelo salino y fertilizado en un huerto frutícola. Revista

Argentina de la Ciencia del Suelo. 35: 47-55.

4. Azpilicueta,

C.; Aruani, M.; Morales, J. 2017. Efecto del tipo de cobertura vegetal en el

espacio entre hileras de perales sobre la abundancia de nematodos fitófagos.

Revista Facultad de Agronomía. La Plata. 116: 249-257.

5. Bonkowski,

M.; Cheng, W.; Griffiths, B.; Alphei, J.; Scheu, S. 2000. Microbial-faunal

interactions in the rhizosphere and effects on plant growth. 2000. European

Journal of Soil Biology. 36: 135-147. DOI: 10.1016/S1164-5563(00)01059-1

6. Caveness, F.;

Jensen, H. 1955. Modification of the centrifugal-flotation technique for the

isolation and concentration of nematodes and their eggs from soil and plant

tissue. Proceedings of the Helminthological Society of Washington. 22: 87-89.

7. Ciobanu, M.;

Popovici, I.; Zhao, J.; Stoica, I. 2015. Patterns of relative magnitudes of

soil energy channels and their relationships with environmental factors in

different ecosystems in Romania. Scientific Report. 5: 17606. DOI:

10.1038/srep17606

8. Di Rienzo,

J.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M.; González, L.; Tablada, M.; Robledo, C.

InfoStat versión 2020. Grupo InfoStat. FCA. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba.

Argentina.

9. Djigal, D.;

Chabrier, C.; Duyck P.; Achard, R.; Quénéhervé P.; Tixier, P. 2012. Cover crops

alter the soil nematode food web in banana agroecosystems. Soil Biology &

Biochemistry 48: 142-150. DOI: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.01.026

10. Dupont, S.;

Ferris, H.; Horn, M. 2009. Effects of cover crop quality and quantity on

nematode-based soil food webs and nutrient cycling. Applied Soil Ecology. 41:

157-167. DOI:10.1016/j.apsoil.2008.10.004

11. Ewald, M.;

Glavatska, O.; Ruess, L. 2020. Effects of resource manipulation on nematode

community structure and metabolic footprints in an arable soil across time and

depth. Nematology. 22: 1025-1043. DOI: 10.1163/15685411-bja10009

12. Ferris, H.;

Bongers, T.; De Goede, R. 2001. A framework for soil food web diagnostics:

Extension of the nematode faunal analysis concept. Applied Soil Ecology. 18:

13-29. DOI:10.1016/S0929-1393(01)00152-4

13. Ferris, H.;

Bongers, T. 2006. Nematode indicators of organic enrichment. Journal of

Nematology. 38: 3-12.

14. Ferris, H. 2010.

Form and function: Metabolic footprints of nematodes in the soil food web. European Journal

of Soil Biology . 46: 97-104. DOI:10.1016/j.ejsobi.2010.01.003

15. Galeazzi,

J.; Alvarez, O. 1998. Determinación de áreas afectadas por niveles freáticos

críticos en el Alto Valle de Río Negro. Congreso Latinoamericano y Argentino de Ingeniería Rural. La Plata. Argentina.

16. Gebremikael,

M.; Steel, H.; Buchan, D.; Bert, W.; De Neve, S. 2016. Nematodes enhance plant

growth and nutrient uptake under C and N-rich conditions. Scientific Reports.

6: 32862. DOI: 0.1038/srep32862www

17. Hernanz, J.;

Sánchez-Guirón, V.; Navarrete, L. 2009. Soil carbon sequestration and

stratification in a cereal/leguminous crop rotation with three tillage systems

in semiarid conditions. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment. 133: 114-122.

DOI:10.1016/j.agee.2009.05.009

18. Horiuchi,

J.; Prithiviraj, B.; Bais, H.; Kimball, B.; Vivanco, J. 2005. Soil nematodes

mediate positive interactions between legume plants and rhizobium bacteria. Planta.

222: 848-857.

19. Jobbágy, E.;

Jackson, R. 2000. The vertical distribution of soil organic carbon and its

relation to climate and vegetation. Ecological Applications. 10: 423-436. DOI:10.2307/2641104

20. Kätterer,

T.; Bolinder, M.; Andrén, O.; Kirchmann, H.; Menichetti, L. 2011. Roots

contribute more to refractory soil organic matter than aboveground crop

residues, as revealed by a long-term field experiment. Agriculture Ecosystems

and Environment. 141: 184-192. DOI:10.1016/j.agee.2011.02.029

21. Leslie, A.;

Wang, S.; Meyer, S.; Marahatta, S.; Hooks, C. 2017. Influence of cover crops

and arthropods, free-living nematodes, and yield in a succeeding no-till

soybean crop. Applied Soil Ecology. 117-118: 21-31.

DOI:10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.04.003

22. Liu, J.;

Khalaf, R.; Ulén, B.; Bergkvist, G. 2013. Potential phosphorus release from

catch crop shoots and roots after freezing-thawing. Plant & Soil. 371:

543-557.

23. Nolla, A.;

Jucksh, I.; Castaldo, J.; Alvarenga, R.; Albrecht, L. 2018. Growth and

accumulation of nutrients by weeds, in maize and legumes intercrops. Planta

Daninha. 36: 1-11. DOI:10.1590/s0100-83582018360100096

24. Ou, W.;

Liang, W.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Q.; Wen, D. 2005. Vertical distribution of soil

nematodes under different land use types in an aquic brown soil. Pedobiologia.

49: 139-148. DOI:10.1016/j.pedobi.2004.10.001

25. Parfit, R.;

Yeates, G.; Ross, D.; Schon, N.; Mackay, A.; Wardle, D. 2010. Effect of

fertilizer, herbicide and grazing management of pastures on plant and soil

communities. Applied Soil Ecology. 45: 175-186.

DOI:10.1016/j.apsoil.2010.03.010

26. Raffo

Benegas, M.; Rodríguez, A. 2007. Factores que afectan el porcentaje de fruta

asoleada en manzanos cv. Fuji en el Alto Valle de Río Negro y Neuquén. RIA. 36:

31-146.

27. Rahman, L.;

Whitelaw-Weckert, M.; Hutton, R.; Orchard, B. 2009. Impact of floor vegetation

on the abundance of nematode trophic groups in vineyards. Applied Soil Ecology.

42: 96-106. DOI:10.1016/j.apsoil.2009.02.006

28. Rasse, D.;

Rumpel, C.; Dignac, M. 2005. Is soil carbon mostly root carbon? Mechanisms for

a specific stabilisation. Plant & Soil. 269: 341-356. DOI -

10.1007/s11104-004-0907-y

29. Rodríguez,

A. M.; Jacobo, E. J.; Grimoldi, A. A.; Golluscio, R. A. 2022. Glyphosate

sprayed on the pre-existing vegetation reduces seedling emergence and growth of

forage species. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad

Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 54(1): 35-45

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.063.

30. Sánchez, E.;

Giayetto, A.; Cichón, L.; Fernández, D.; Aruani, M.; Curetti, M. 2007. Cover

crops influence soil properties and tree performance in an organic apple (Malus

domestica Borkh) orchard in northern Patagonia. Plant and Soil. 292:

193-203. DOI:10.1007/s11104-007-9215-7

31. Scharroba,

A.; Kramer, S.; Kandeler, E.; Ruess, L. 2016. Spatial and temporal variation of

resource allocation in an arable soil drives community structure and biomass of

nematodes and their role in the micro-food web. Pedobiology. 59: 111-120.

DOI:10.1016/j.pedobi.2016.03.005

32.

Sieriebriennikov, B.; Ferris, H.; de Goede, R. 2014. NINJA: an automated

calculation system for nematode-based biological monitoring. European Journal

of Soil Biology . 61: 90-93. DOI:10.1016/j.ejsobi.2014.02.004

33. Sohlenius,

B.; Sandor, A. 1987. Vertical distribution of nematodes in arable soil under

grass (Festuca pratensis) and barley (Hordeum distichum). Biology

& Fertility of Soils. 3: 19-25.

34. Soil Survey

Staff. 2014. Keys to Soil Taxonomy. 12th ed. USDA. Natural Resources

Conservation Service, Washington. DC. USA.

35. Sozzi, G.

2007. Árboles frutales. Ecofisiología, cultivo y aprovechamiento. Editorial

Facultad de Agronomía. Universidad de Buenos Aires. Argentina. 803 p.

36. Su, Y.; Liu,

T.; Wang, X.; Yang, R. 2016. Salinity effects on soil organic carbon and its

labile fractions and nematode communities in irrigated farmland in an arid

region, northwestern China. Science in Cold and Arid Regions. 8: 47-53.

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1226.2016.00046

37. Viketoft,

M.; Bengtsson, J.; Sohlenius, B.; Berg, M.; Petchey, O.; Palmborg, C.;

Huss-Danell, K. 2009. Long-term effects of plant diversity and composition on

soil nematode communities in model grasslands. Ecology. 90: 90-99.

DOI:10.1890/08-0382.1

38. Wardle, D.;

Yeates, G.; Bonner, K.; Nicholson, K.; Watson, R. 2001. Impacts of ground

vegetation management strategies in a kiwifruit orchard on the composition and

functioning of the soil biota. Soil Biology & Biochemistry. 33: 893-905.

DOI: 10.1016/S0038-0717(00)00235-2

39. Yeates, G.

1980. Population of nematode genera in soils under pasture. III: Vertical

distribution at eleven sites. N. Z. Journal of Agricultural Research. 23:

117-128. DOI: 10.1080/00288233.1980.10417855

40. Yeates, G.;

Bongers, T.; De Goede, R.; Freckman, D.; Georgieva, S. 1993. Feeding habits in

soil nematode families and genera - An outline for soil ecologists. Journal of

Nematology. 25: 315-331.

41. Zhang, X.;

Ferris, H.; Mitchell, J.; Liang, W. 2017. Ecosystem services of the soil food

web after long-term application of agricultural management practices. Soil

Biology & Biochemistry. 111: 36-43. DOI:10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.03.017