Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 55(2). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2023.

Original article

Apple (Malus domestica) and pear (Pyrus communis) yield

prediction after tree image analysis

Detección

de manzanas (Malus domestica) y peras (Pyrus communis) a partir

de imágenes para pronósticos de producción

Valentin Tassile3,

Sergio Jorge Bramardi2,

Darío Eduardo Fernández1,

Pablo Daniel Reeb2

1Estación experimental Ing. Agr. Carlos H Casamiquela. Instituto

Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria. Ruta Nacional 22. km 1190. C.

P. 8328. Allen. Rio Negro.

2Universidad Nacional del Comahue. Departamento de Estadística.

Buenos Aires 1400. C. P. 8300. Neuquén. Capital.

3Universidad

Nacional del Comahue. Facultad de Ciencia y Tecnología de los Alimentos. 25 de

Mayo y Reconquista. C.

P. 8336. Villa Regina. Río Negro.

*delbrio.dolores@inta.gob.ar

Abstract

Yield forecasting depends on accurate tree fruit counts and mean size

estimation. This information is generally obtained manually, requiring many

hours of work. Artificial vision emerges as an interesting alternative to

obtaining more information in less time. This study aimed to test and train

YOLO pre-trained models based on neural networks for the detection and count of

pears and apples on trees after image analysis; while also estimating fruit

size. Images of trees were taken during the day and at night in apple and pear trees while fruits were manually counted. Trained

models were evaluated according to recall, precision and F1score. The

correlation between detected and counted fruits was calculated while fruit size

estimation was made after drawing straight lines on each fruit and using

reference elements. The precision, recall and F1score achieved by the models

were up to 0.86, 0.83 and 0.84, respectively. Correlation coefficients between

fruit sizes measured manually and by images were 0.73 for apples and 0.80 for

pears. The proposed methodologies showed promising results, allowing

forecasters to make less time-consuming and accurate estimates compared to

manual measurements.

Keywords: Fruit detection, Artificial

visión, Yield forecast, Malus domestica, Pyrus communis

Resumen

Para pronosticar la

producción es necesario contar el número de frutos de los árboles y estimar el

tamaño medio. Esta información se obtiene manualmente y requiere mucha mano de

obra experimentada. La visión artificial surge como alternativa para obtener

más información en menos tiempo. Los objetivos del trabajo fueron entrenar

modelos de visión artificial para detectar y contar el número de peras y

manzanas en árboles a partir de imágenes; y medir diámetros de frutos en

imágenes. Se usaron modelos pre-entrenados para detección de objetos basados en

redes neuronales (YOLO). Se tomaron imágenes de árboles de día y de noche, y

los frutos de cada planta fueron contados manualmente. Los modelos se evaluaron

según sensibilidad, precisión y F1score; y se calculó la correlación entre

frutos detectados y contados. La estimación de diámetros se realizó trazando

líneas rectas sobre cada fruto y utilizando elementos de referencia. La

precisión, sensibilidad y F1score alcanzados por los modelos fueron 0,86, 0,83

y 0,84, respectivamente. Las correlaciones entre diámetros medidos manualmente

y por imágenes fueron de 0,73 en manzanas y 0,80 en peras. Las metodologías

propuestas permitieron realizar estimaciones a partir de imágenes con una

precisión aceptable y en menor tiempo respecto de las mediciones manuales.

Palabras clave: Detección de frutos, Visión

artificial, Predicción de cosecha, Malus domestica, Pyrus communis

Originales: Recepción: 05/12/2022

- Aceptación: 02/08/2023

Introduction

Yield prediction constitutes a major challenge in pear and apple

orchards. Early yield forecasts allow growers to estimate final fruit volume,

calculate necessary supplies for fruit picking, plan

and manage storage spaces, book grading facilities and transport (34).

Nevertheless, estimating yield in fruit crops is not easy given that

fruit crops are perennial species in which small variations in cultural

techniques or differences in cultivar genotype define greater production variability

(3). Additionally, annual yield depends

on climatic and management conditions that affect flowering, fruit set, growth

and persistence on the plant until harvest (2).

Furthermore, forecasts are generally based on manual counting of fruit in selected

trees. This method is extremely time-consuming and the number of inspected

trees is generally small, adding inaccuracy (30).

In this scenario, image analysis becomes one crucial alternative.

Image processing techniques in fruit production have increased

significantly in the last few years. Fruit detection after image analysis has

been used for many purposes like yield forecast (1,

9, 11, 30, 34), improvement in thinning decisions (12, 14), and robotic harvesting (23, 32).

Different proximal sensors can be used with computer vision aims (13). Several studies have used simple sensors

like black and white cameras (24), or

more complex multispectral ones (5).

However, most methodologies developed so far, base their analysis on colour

digital images (also called RGB images: Red, Green and Blue). In addition,

image analysis is done after different strategies, from those based on colour

features to modern techniques such as machine learning. Four basic features

characterize objects in images: intensity, colour, shape and texture. All of

them can recognize flowers or fruits. Colour is one of the most important image

features to distinguish fruits from leaves. However, it is affected by

variations in fruit colour, maturity, variety and varying environment (13). In this way, while colour and intensity

analysis is faster, shape analysis is more robust (23).

Some fruit detection algorithms have been solely developed from colour features

(7, 11, 34).

Other more complex algorithms integrate colour, texture and shape features (14, 19, 21, 23, 25, 30).

Nevertheless, machine learning and especially deep learning appears to

be the most promising technique. Many authors suggest that deep learning

achieves better results in image analysis than classical programming methods,

though they require high computational resources (13).

According to Koirala et al. (2019a), computational resources are not a problem anymore, as

having a Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) nowadays turns easy. Free available online

tools consist of graphical annotation apps and last-generation deep learning

models like Faster R-CNN (Faster Regional Convolutional Neural Network) (27), Single Shot MultiBox Detector (SSD) (22), or YOLO (You Only Look Once) (26).

Previous research has trained deep learning models for fruit detection

with promising results in rock melons, strawberries, apples, avocados, mangos,

oranges and sweet pepper (28); apples,

mangos and almonds (4); mangos (18); oranges and apples (8); apples and pears (6,

15); apples in different growth stages (31);

apple fruitlets before thinning (33).

Although fruit detection from image analysis has been studied for a long

time, in the field, variable lighting conditions constitute a disadvantage (23). In addition, fruit detection and

localization are affected by the complex canopy structures (16) and accuracy is limited by the occlusion of

fruits among leaves, branches and other fruits in the image (13). Finally, to the present, only a few studies

conduct fruit detection and counting on pear trees. Also, pear trees, unlike

apple ones, generally have a more complex crown structure and fruits remain

green until they mature. Due to these characteristics, model training needs to

be separately done for each species. This study aimed to i) evaluate deep

learning models for apple and pear detection and counting with yield forecast

purposes, and ii) measure fruit sizes from images.

Materials and methods

Experimental plot

The trial was carried out in two plots at the Instituto Nacional de

Tecnología Agrpecuaria (INTA) Experimental Station, Allen, Argentina

(39°01’33.6’’ S, 67°44’27.8’’ W). Apple cultivar was ‘Red Chief’ grafted on

MM111 rootstock planted in 2000. Trees were trained as espalier at a distance

of 1.5 m between trees by 4 m between rows, in a total area of 0.8 ha, with a

total of 1280 trees. The pear cultivar was ‘Williams Bon Chretien’ grafted on

seedling rootstock and planted in 2003. Trees were trained as espalier, at a

distance of 4 m between rows by 2 m between trees, in a total area of 1.8 ha

with a total of 2016 trees.

Data collection

Images were taken during four seasons from 72 apple trees and 60 pear

trees per season. In the pear plot, 3 trees were randomly selected at 20

representative rows, totalling 60 trees. In the apple plot, 8 trees were

randomly selected from 9 representative rows, totalling 72 trees.

Images were captured when the pears reached an average diameter of 40 mm

and apples 35 mm approximately (first week of December) in two different

conditions: i) natural daylight between 10 am and 1 pm, ii) at night with the

artificial flash light of the camera. Images were captured on a partly cloudy

day to minimize undesirable effects caused by direct sunlight (11). A black curtain was unfolded behind the

trees avoiding interference from neighbouring trees (1).

All images were taken with an RGB digital camera (Cannon of 12 MP) from a

distance of approximately 3.0 m from the tree and transversely to the row. A

square object of 15 cm by 15 cm dimension was placed next to each tree as scale

for size estimations.

The same day, images were captured, and all fruits on each photographed

tree were manually counted by a single operator. Three records were made in

each tree: i) fruit number on the same side of the image; ii) fruit number on

the other side of the image; iii) total fruit number. At harvest time, weight

and number of fruits collected were recorded for each tree. In addition, the

number of apples and pears was visually determined from the fruit images (human

eyes) by the same person.

Fruit detection and counting from image

analysis

The deep learning models trained for fruit detection and counting were

YOLO in different versions: YOLOv5s6 and YOLOv7, available in the github

repository: https://github.com/AlexeyAB/darknet. Pear and apple detection and counting training were done

separately. For apples, the selected version was YOLOv5s6 with an image

resolution of 1024x1024 pixels because YOLOv7 showed a similar performance to

YOLOv5s6, but had a much more complex structure. For pears, the selected

version was YOLOv7 with an image resolution of 1280x1280 pixels because

YOLOv5s6 showed poor performance for this specie. Roboflow was used to label

images with apples or pears categories. The apple dataset had 505 images with a

total of 36260 annotations (fruits) and the pear dataset had 474 images with a

total of 39052 annotations (fruits). Some low-quality images were removed from

the datasets. Each dataset was divided into three parts: training set (70%), validation set (20%) and testing set (10%). Also, to

increase the number of images and generate more information, augmentation

techniques were used in both datasets. Deep-learning-model performance was

evaluated based on: i) precision, which gives the number of true detection out

of total detection, calculated as precision=true positives/(true positives +

false positives); ii) recall, number of true detections out of total truth

annotations, calculated as recall=true positives/(true positives + false

negatives); iii) F1 Score, a weighted average of precision and recall, varying

between 0 (worst) and 1 (best), calculated as F1score=2*(precision*recall/

(precision + recall)), (17).

Pearson correlation coefficients compared model results and manual

counts between i) the number of manually counted fruits on the same side of

image collection; ii) the number of total manually counted fruits in the tree;

iii) the number of labelled fruits in the images (human eye detection in

images); iv) the number of detected fruits by deep learning models (artificial

vision detection); v) number of harvested fruits per tree.

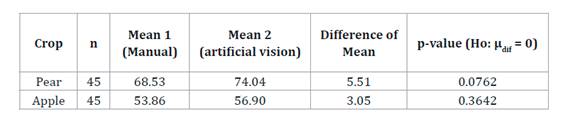

A paired-sample t-test revealed significant differences between the

number of manually counted fruits on the same side of the image collection and

the number of detected fruits by deep learning models (artificial vision

detection). Normally distribution was verified by Shapiro-Wilks test and mean

differences were compared to zero.

Size estimation

Laboratory and field conditions evaluated fruit size estimation. In the

first case, 106 harvested fruits of different sizes were placed in cellulose

trays and numbered. Later, the equatorial diameter was measured manually with a

digital calliper (Essex 150 mm, Stainless Hardened). Then, a 12 MP camera was

used to photograph each tray placing an object of known dimensions by each one.

In the second case, 89 apples and 98 pears were selected from various trees.

For this trial, one row of each crop was randomly selected. Then the object of

known dimensions was placed on some trees of the row. Fruits close to that

object were identified and their equatorial diameter was measured.

Image analysis was done with ImageJ software (26).

Fruit diameters were measured by drawing a straight line in the equatorial

diameter of each fruit.

Finally, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between the

manually measured diameter and the image-measured diameter for each situation

analyzed. In addition, differences between manually measured diameter and

image-measured diameter were calculated and divided by the mean of the manually

measured diameter. Finally, frequency distributions were plotted.

Results and discussion

Fruit detection and counting from image

analysis

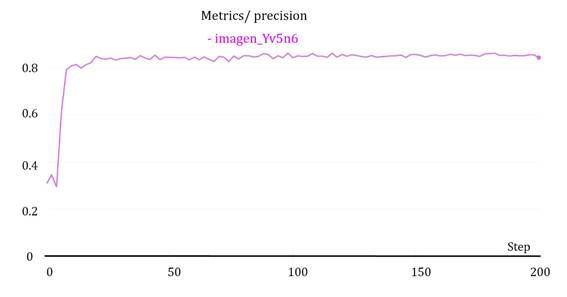

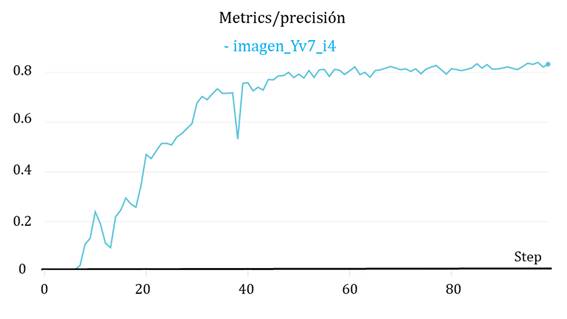

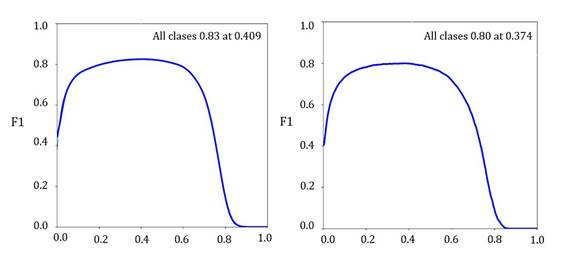

Precision

values achieved were 0.86 (Figure 1) and 0.87 (Figure

2) for apples and pears, respectively, while recall was 0.83 for both

species, and F1 Score were 0.83 and 0.80 for apples and pears, respectively (Figure 3).

Obtained from https://wandb.ai/delbrio/yolov5s-W?workspace=user-delbrio

Figure 1. Precision graph for DL model trained for apple

detection and counting.

Figura

1. Gráfico de precisión del

modelo entrenado para detección y conteo de manzanas.

Obtained from https://wandb.ai/delbrio/yolov5s-W?workspace=user-delbrio

Figure 2. Precision graph for DL model trained for

pear detection and counting.

Figura

2. Gráfico de precisión del

modelo entrenado para detección y conteo de peras.

Obtained from https://wandb.ai/ delbrio/yolov5s-

W?workspace=user-delbrio

Figure 3. Left: F1 score graph for DL model trained for apple

detection and counting. Right: F1 score graph for DL model trained for pear

detection and counting.

Figura

3. Derecha: Gráfico de F1 score

del modelo entenado para detección y conteo de peras. Izquierda: Gráfico de F1

score del modelo entenado para detección y conteo de manzanas.

Obtained

values were lower than the 0.9 presented by Sa et al. (2016) for melon, raspberry, apple, orange, mango, avocado and

pepper with Faster R-CNN and VGGNet. These authors worked with their own images

for pepper and melon, and Web images for the rest of the fruits demonstrating

model robustness. The higher values obtained by these authors could be due to

the images including fruits in different maturity stages with different

colouration from the rest of the plant. They also considered a part of the

plant instead of the whole plant, with fruits occupying a greater proportion of

the image. Our trial only used whole-plant images taken under natural

conditions with smaller fruits in relation to the total image.

One

difficulty faced in this study was model ability to detect all fruits in the

clusters, also one main error source reported by Bargoti and Underwood (2017), in their apple, mangos and almond detection models.

According to Koirala et al. (2019b), values obtained by those authors could be lower than

other reference values because images were influenced by environmental

conditions, crop characteristics, and number of fruits per image (100 for

mangoes and apples, and up to 1000 for almonds). This study faced the same

issue as fruit number per image ascended to 170 and 150 in pears and apples,

respectively.

In the present trial, both daylight and night artificial light images

were used. The former could decrease model accuracy due to environmental light

conditions. Koirala et al. (2019b) evaluated many existing deep learning models and built a

hybrid MangoYOLO which combined speed and precision criteria. They mentioned

that better results were obtained from images taken at night with artificial

light, while under natural daylight conditions, the percentage of false

positives increased significantly.

Another drawback in fruit detection also evidenced in this trial,

especially in pears, is the different tree leaf densities and fruit occlusion

by leaves, branches and other fruits. These and the distinct angles to capture

images were also major difficulties mentioned by Liang et al. (2018),

who achieved precision values of 0.97 and 0.92 and recall values of 0.63 and

0.90 for mango detection with two different alternatives of Faster R-CNN

models. F1 values were between 0.79 and 0.91.

The training number of images is a main factor (6). These authors reported F1 scores between 0.79

and 0.89 depending on the amount of images used. Chen et al. (2016)

also reported lower results of F1 Score (0.76) than those obtained in this

study, probably due to the lower number of images used (71 daylight orange

images and 21 nightlight apple images).

Moreover, fruit growth stage may affect the results of this trial.

Intending to achieve yield forecast, fruit detection and counting from images

at growth stages turns crucial. Tian et

al. (2019) evaluated the YOLOv3 performance

during different apple growth stages. F1 scores were 0.83, 0.84, 0.86 and 0.82

for young, growing, ripen and total apples, respectively. Values reported for

growing apples were very close to those obtained in this trial. The highest

values obtained were for ripened apples, probably due to ripened fruit having a

larger size and a different colour compared to the rest of the plant.

Other trials using videos showed promising results probably because many

images could be taken from different angles, making fruits more visualized (15). They trained YOLOv2 and YOLOv3, with average

precision ranging from 0.88 to 0.97. Images obtained in our study were always

taken from the same angle and distance.

Correlation analysis

Correlation coefficients between labelled and harvested fruits reached

0.89 and 0.62 for apples and pears, respectively, suggesting images provided a

close approximation of apple number when forecasting. Correlation values were

lower for pears, suggesting more complex image prediction. This is given to

pear trees being larger than apple ones, with longer branches and more foliage.

In addition, at the moment of image capture, fruits were still small and green

so detection was more difficult. This agrees with Zhou et al. (2012),

who concluded that if prediction was early, many apples might remain hidden due

to size and colour.

Harvested fruits vs. manual counts of total plant reached values

up to 0.94 and 0.82 for apples and pears, respectively. These values were

higher than those obtained between harvested fruits vs. manual counts

only on the image side (0.91 and 0.70 for apples and pears, respectively). This

highlights the need to capture images on both sides of the plant for better

predictions. Dorj et al. (2017),

used three and up to four images per tree to detect and count fruits from

citrus images. That is, a higher number of images per tree could improve the

results obtained in this trial. On the contrary, Linker

(2016) concluded that more images per tree did

not throw better results.

Finally,

the correlation coefficient for manual fruit counts per tree and that detected

by a deep learning model trained from images (Photo) was

up to 0.88 and 0.73 for apples and pears, respectively. These results showed

how models accurately detected fruit in the analyzed images, constituting an

interesting alternative to traditional manual counting. Črtomir et al. (2012), in their hybrid harvest prediction model, achieved

similar results in this work for ‘Golden Delicious’ apples (between 0.73 and

0.83) while for Braeburn’ apples, results showed more variability (between 0.51

and 0.78). On the other hand, Farjon et al. (2019), used convolutional neural networks for flower detection

in ‘Golden Delicious’ apples and achieved correlations between estimated

numbers and those calculated by a group of experts of between 0.78 and 0.93.

Photo. Image of an apple tree with box predictions obtained from DL model

identified with labels.

Foto.

Foto de un árbol

de manzana con las predicciones realizadas por el modelo de DL entrenado,

identificadas con etiquetas.

The results obtained in this trial could be affected by fruit growth

development at the moment of image taking. Stajnko et al. (2005),

worked with apple images taken at five different fruit growth moments and

ripening periods. They achieved correlation coefficients between 0.71 and

0.91, according to moment and cultivar. Considering that the highest values

corresponded to fruits closer to maturity, their results would be similar to

those obtained in this trial.

Mean differences between the number of manually counted fruits on the

same side of image collection and the number mean of detected fruits by deep

learning models (artificial vision detection) showed non-significant

differences with respect to zero (Table 1), for both pears

and apples (p-value>0.05).

Table 1. Hypothesis test on the equality to zero of mean differences between the

number of fruits detected by Deep Learning models (artificial vision) and

number of fruits counted manually on the same side of pear and apple trees.

Tabla 1. Prueba de hipótesis sobre la igualdad a cero de la media de las diferencias entre la cantidad de frutos detectados por los modelos de Depp Learning (vision artificial) y cantidad de frutos contados manualmente sobre el mismo lado del árbol para el cultivo de pera y manzana.

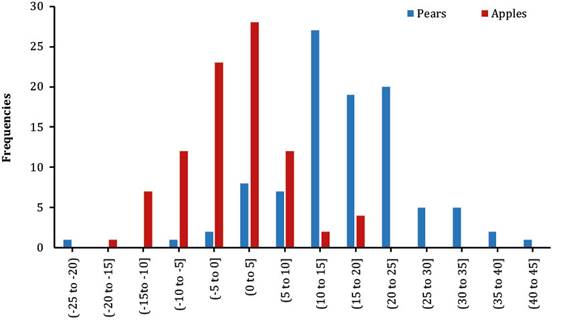

Size estimation

Correlation

coefficients obtained between manually measured diameter and image diameter

were 0.89 for laboratory fruits, 0.73 for field apples and 0.80 for field

pears. Laboratory fruits showed higher correlation than field ones, probably

given by fruit position in the tree being much more variable than in the

laboratory. In addition, fruits hanging far from the object of known dimensions

used as scale could increase error. To improve this methodology in the future,

measuring should only consider fruits close to the scaling object or the

placement of more scaling objects per image. Stajnko et al. (2005) also worked on estimating fruit diameters at different

growing stages from ‘Golden Delicious’ and ‘Gala’ apple images obtaining highly

variable coefficients with values ranging from 0.19 to 0.79 for ‘Golden

Delicious’ and 0.34 to 0.88 for ‘Gala’. Different values correspond to

different fruit growth stages and seasons. Low correlation coefficients could

be due to the algorithm based on the longest segment fruit measurement. Some

values found by these authors resulted similar to those in this trial. Stajnko et al. (2009) also concluded an

overestimation of the diameters in ‘Jonagold’ and ‘Golden Delicious’ apples

when images were taken in young fruits, while underestimation occurred in

ripened fruits. These results differed from those we found for pears since

ripen ones were overestimated. On the other hand, apple results were variable,

showing both diameters under and overestimation (Figure 4).

Differences

between manual diameter measurements and image diameter measurements (% with

respect to the mean of manual diameter measurements).

Diferencias entre los

diámetros medidos manualmente y los medidos a partir de imágenes (expresados en

% respecto de la media de las mediciones manuales).

Figure 4. Frequency distribution for differences between image

diameter measurements and manual diameter measurements divided by mean manually

measured diameter in apples and pears.

Figura

4. Gráfico de distribución de

frecuencias para las diferencias entre los diámetros medidos por imágenes y los

medidos manualmente divididos por la media de los diámetros medidos manualmente

en peras y manzanas.

Conclusion

Fruit number on both apple and pear trees could be estimated from images

with promising results. They could be improved by increasing the amount of

input data to the deep learning models. This includes more image

taking in many different conditions (angles, distances to the focus, fruit

growth stages, tree size, spacing, age and management conditions).

The possibility of estimating fruit number from images could reduce time

costs, allowing growers to increase the number of sampled trees for yield

forecasts.

Fruit size estimation from images was not accurate in this study,

varying according to fruit proximity to the scaling object. Fruit size

estimation also depends on fruit position on the tree and consequent

visibility.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Instituto Nacional de Tecnología

Agropecuaria (INTA), Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas

(CONICET) and Universidad Nacional del Comahue (PI E115).

1. Aggelopoulou,

A. D.; Bochtis, D.; Fountas, S.; Swain, K. C.; Gemtos, T. A.; Nanos, G. D.

2011. Yield prediction in apple orchards based on image processing. Precision Agriculture. 12: 448- 456.

doi.org/10.1007/s11119-010-9187-0

2. Aruani, M.

C.; Reeb, P. D.; Barnes, N. E. 2014. Influence of soil properties on yield and

fruit maturity at harvest of ‘Williams’ pear. Chilean journal

of agricultural research. 74(4): 460-467. doi.

org/10.4067/S0718-58392014000400013

3. Avanza, M.

M.; Bramardi, S. J.; Mazza, S. M. 2010. Optimal sample size for evaluate the

growth pattern of ‘Valencia late’ orange fruit. Revista

Brasileira de Fruticultura. Jaboticabal. 32(4): 1154- 1163.

4. Bargoti, S.;

Underwood, J. 2017. Deep fruit detection in orchards. arXiv:1610.03677.v2[cs.RO]

5. Best,

S.; Salazar, F.; Bastías, R.; Leon, L. 2008. Crop load

estimation model to optimize yield - quality ratio in apple orchards, Malus

Domestica Borkh, Var. Royal

Gala. Journal of Information Technology in Agriculture. 3: 11-18.

6. Bresilla, K.;

Demetrio Perulli, G.; Boini, A.; Morandi, B.; Corelli Grappadelli, L.;

Manfrini, L. 2019. Single-Shot convolution neural networks

for real-time fruit detection within the tree. Front. Plant.

Sci. 10: article 611. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.00611

7. Bulanon, D.

M.; Kataoka, T.; Ota, Y.; Hiroma, T. 2002. A segmentation algorithm for the

automatic recognition of fuji apples at harvest.

Biosystem Engineering. 83: 405-412. https:// doi.

org/10.1006/bioe.2002.0132

8. Chen, S. W.;

Shivakumar, S. S.; Dcunha, S.; Das, J.; Okon, E.; Qu, Taylor, C. J.; Kumar, V.

2016. Counting apples and oranges with deep learning: a data driven approach. IEEE robotics and automation letters. 2(2): 781-788.

https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2017.2651944

9. Cohen, O.;

Linker, R.; Naor, A. 2011. Estimation of the number of apples in color images

recorded in orchards. International Federation for Information Processing, Part

I, AICT. 344: 630-642.

10. Črtomir, R.;

Urška, C.; Stanislav, T.; Denis, S.; Karmen, P.; Pavlovič, M. 2012. Application of neural networks and image visualization for early

forecast of apple yield. Erwerbs-Obstbau. 54:

69-76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10341-012-0162-y

11. Dorj, U.;

Lee, M.; Yun, S. 2017. An yield estimation in citrus

orchards via fruit detection and counting using image processing. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. 140: 103-112.

https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2017.05.019

12. Farjon, G.;

Krikeb, O.; Bar, A.; Victor, H. 2019. Detection and counting

of flowers on apple trees for better chemical thinning decisions. Precision

Agriculture . 21: 503-521. https://doi.

org/10.1007/s11119-019-09679-1

13. Gongal, A.;

Amatya, S.; Karkee, M.; Zhang, Q.; Lewis, K. 2015. Sensors and systems for

fruit detection and localization: A review. Computers and

Electronics in Agriculture. 116: 8-19. https://

doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2015.05.021

14. Hočevar, M.;

Širok, B.; Godeša, T.; Stopar, M. 2014. Flowering estimation

in apple orchards by image analysis. Precision

Agriculture . 15: 466-478.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-013-9341-6

15. Itakura, K.;

Narita, Y.; Noaki, S.; Hosoi, F. 2021. Automatic pear and apple detection by

videos using deep learning and a Kalman filter. Osa Continuum. 14(5):

1688-1695. https://doi. org/10.1364/OSAC.424583

16. Karkee, M.;

Zhang, Q. 2012. Mechanization and automation technologies in specialty crop

production. Resource Magazine. 19(5): 16-17.

https://doi.org/10.13031/2013.42314

17.

Koirala, A.; Walsh, K. B.; Wang, Z.; McCarthy, C. 2019a. Deep

Learning - Method overview and review of use for fruit detection and yield

estimation. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture.

162: 219-234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2019.04.017

18.

Koirala, A.; Walsh, K. B.; Wang, Z.; McCarthy, C. 2019b. Deep

learning for real-time fruit detection and orchard fruit load estimation:

benchmarking of ‘MangoYOLO. Precision Agriculture . 20: 1107-1135.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-019-09642-0

19. Kurtulmus,

F.; Suk, W.; Vardar, A. 2011. Green citrus detection using ‘eigenfruit’, color

and circular Gabor texture features under natural outdoor conditions. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. 78(2): 140-149.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2011.07.001

20. Liang, Q.;

Zhu, W.; Long, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W.; Wu, W. 2018. A

real-time detection framework for on-tree mango based on SDD Network. Springer Nature Switzerland. 10985: 423-436.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97589-4_36

21. Linker, R.

2016. A procedure for estimating the number of green mature apples in

night-time orchard images using light distribution and its application to yield

estimation. Precision Agriculture . 18: 59-75.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-016-9467-4

22. Liu, W.;

Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C. Y.; Berg, A. C. 2016.

SSD: Single shot multi box detector. Computer Vision ECCV Lecture Notes in

Computer Science.. 9905: 21- 37.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-46448-0_2

23. Mao, W.;

Jia, B.; Zhang, X.; Hub, X. 2009. Detection and position

method of apple tree image. Computer and Computing

Technologies in Agriculture II. IFIP Advances in

Information and Communication Technology. 2: 1039-1048.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0211-5_29

24. Parrish, E.

A.; Goksel, A. K. 1977. Pictorial pattern recognition applied to fruit

harvesting. ASAE. 20(5): 822-827.

https://doi.org/10.13031/2013.35657

25. Qureshi, W.

S.; Payne, A.; Walsh, K. B.; Linker, R.; Cohen, O.; Dailey, M. N. 2016. Machine vision for counting fruit on mango tree canopies. Precision

Agriculture . 18: 224-244. https://doi.

org/10.1007/s11119-016-9458-5

26. Rasband, W.

S. 1997-2018. ImageJ.. U. S. National Institutes of

Health Bethesda. Maryland. USA. https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/

27. Redmon, J.;

Farhadi, A. 2018. YOLO v3: An incremental improvement. ArXiv:1804.02767.

https:// doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1804.02767

28. Ren, S.; He,

K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. 2015. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object

Detection with Region Proposal Networks. Advances in Neural Information

Processing Systems, arXiv:1506.01497.

https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1506.01497

29. Sa, I.; Ge,

Z.; Dayoub, F.; Upcroft, B.; Perez, T.; Mccool, C. 2016. DeepFruits: A Fruit

Detection System Using Deep Neural Networks. Sensors.

16(8): 1-23. https://doi.org/10.3390/s16081222

30.

Stajnko, D.; Èmelik, Z. 2005. Modelling of apple fruit growth

by application of image analysis. Agriculturae

Conspectus Scientificus. 70(2): 59-64.

31. Stajnko, D.;

Rakun, J.; Blanke, M. 2009. Modelling apple fruit yield using image analysis

for fruit colour, shape and texture. European Journal of

Horticultural Science. 74(6): 260-267.

32. Tian, Y.;

Yang, G.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, E.; Liang, Z. 2019. Apple detection during

different growth stages in orchards using the improved YOLO-V3 model. Computers and electronic in agriculture. 157: 417-426.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2019.01.012

33. Wachs, J.

P.; Stern, H. I.; Burks, T.; Alchanatis, V. 2010. Low and

high-level visual feature-based apple detection from multi-modal images. Precision

Agriculture . 11: 717-735. https://doi.

org/10.1007/s11119-010-9198-x

34. Wang, D.;

He, D. 2021. Channel Pruned YOLOv5s based-Deep learning approach for rapid and

accurate apple fruitlet detection before fruit thinning. Biosystem

engineering. 210: 271- 281.

https://doi.org/1016/j.biosystemseng.2021.08.015

35. Zhou, R.;

Damerow, L.; Sun, Y.; Blanke, M. M. 2012. Using colour features of cv. ‘Gala’

apple fruits in an orchard in image processing to predict yield. Precision

Agriculture . 13: 568-580.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-012-9269-2