Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 55(2). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2023.

Original article

Health

risk due to pesticide exposure in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) crop in

Oaxaca, Mexico

Riesgo

a la salud por exposición a plaguicidas en el cultivo de tomate (Solanum

lycopersicum) en Oaxaca, México

Héctor Ulises

Bernardino Hernández1*

Honorio Torres

Aguilar1

1Universidad

Autónoma Benito Juárez de Oaxaca. Facultad de Ciencias Químicas. México. Av.

Universidad S/N. Cinco Señores. C. P. 68120. Oaxaca de Juárez. Oaxaca. México.

*hbernardino@yahoo.com

Abstract

Pesticides

increase agricultural productivity worldwide. Unfortunately, these pesticides

put public health and the environment at risk. This study aimed to document the

presence of pests and diseases in tomato crops, the range of pesticides used,

and acute pesticide poisoning symptoms (APP) among producers from various

municipalities in the State of Oaxaca, Mexico. Surveys were applied from 2019

to 2021. The information was examined through a descriptive analysis. The

Mann-Whitney U test and Spearman’s Rho correlation established differences

between groups and associations. The main pests were the white fly, various

worms, blight, mildew, and weeds. Fifty-five active ingredients (AI) were

identified, predominantly Toxicological Category (TC) IV, such as insecticides

and fungicides, as well as TC III herbicides. Factors associated with a greater

diversity of AI were <10 years in agricultural activity, high presence of

pests and diseases, and surfaces >1 ha. Up to six APP symptoms occurred in

60.6% of the producers, and 58.2% of the AI identified are considered hazardous

pesticides.

Keywords: tomato, pest,

pesticides exposure, health, acute pesticide poisoning

Resumen

El uso de

plaguicidas ha sido una estrategia para incrementar la productividad agrícola a

nivel mundial. Lamentablemente, dichos insumos ponen en riesgo la salud pública

y el ambiente. El objetivo del presente estudio, fue documentar la presencia de

plagas y enfermedades en el cultivo de tomate, la diversidad de plaguicidas

utilizados y los síntomas de intoxicación aguda por plaguicidas (IAP) entre

productores de diversos municipios del estado de Oaxaca, México. Se aplicaron

encuestas durante 2019 a 2021. La información se examinó mediante un análisis

descriptivo; para establecer diferencias entre grupos y asociaciones, se empleó

la prueba de U de Mann-Whitney y correlación de Rho de Spearman. Las

principales plagas fueron la mosquita blanca, diversos gusanos, tizón,

cenicilla y malas hierbas. Se identificaron 55 ingredientes activos (IA),

predominando los insecticidas y fungicidas de Categoría Toxicológica (CT) IV y

herbicidas CT III. Los factores que se asociaron al uso de una mayor diversidad

de IA, fueron la incursión <10 años en la actividad agrícola, el incremento

de plagas y enfermedades y las superficies >1 ha. El 60,6% de los productores

manifestaron hasta seis síntomas de IAP. El 58,2% de los IA identificados, son

considerados como plaguicidas altamente peligrosos.

Palabras clave: tomate, plagas,

exposición a plaguicidas, salud, intoxicación aguda por plaguicidas

Originales: Recepción: 27/12/2022 - Aceptación: 12/10/2023

Introduction

Worldwide

agricultural productivity has increased in recent years in parallel with

population growth. The horticultural subsector has grown the most, especially

in medium- and high-income countries (28).

Pesticides have been one of the external agricultural supplies that have

guaranteed increased food production by preventing and controlling various

pests that affect crops (32). In recent

years, the trend in the use and development of pesticides has undergone

modifications. Chemical substances such as organochlorine, organophosphorus,

carbamates, and synthetic pyrethroid are being replaced by products with novel

action mechanisms and unique chemical structures to avoid emerging pesticide

resistance (33) and with apparent lower

danger to public health and the environment. Pesticides are associated with

this process, mainly in crops of high economic value, protecting investment.

Among these crops, tomato is considered one of the most important internationally.

Until 2017, China, India, Turkey, the United States, and Egypt centralized

production; while Mexico ranked ninth worldwide (9).

Until 2020, 54.4% of tomato production in the Mexican Republic was concentrated

in the states of Sinaloa (22.9%), Michoacán (11.7%), Zacatecas (6.8%), San Luis

Potosí (6.6%) and Baja California Sur (6.4%). In that same year, the State of

Oaxaca was in seventeenth place (1.7%), where the Valles Centrales region led

the production (49.9%), followed by Huajuapan de León (15.1%), Istmo (14.5%),

Cañada (14.4%) and Sierra Juárez (6.2%). Greenhouse production reached 62.9%,

compared to open field (37.1%) (29).

Tomato crops are

susceptible to various arthropod insects and a wide variety of diseases caused

by multiple pathogens (fungi, viruses, and bacteria) in the various

phenological phases of growth (pre-harvest and post-harvest), as well as in

different parts of the plant (root, stems, foliage and fruits) (16). These insects and pathogens cause

considerable decrease in yield and consequent high economic losses. Chemical

control using pesticides turns normal.

In recent years,

tomato cultivation has increased in various municipalities of the State of

Oaxaca, particularly in the Valles Centrales region. Currently, for this

region, there is limited information on pathogen diversity or pesticide usage.

Specifically, for San Baltazar Chichicapam, mites, blight, and powdery mildew

have been reported and controlled with abamectin, bifenthrin and mancozeb (26). National reports for various vegetables

evidence indiscriminate use of pesticides of different types (herbicides,

insecticides, and fungicides) belonging to different toxicological categories

and chemical groups (organophosphates, carbamates, dithiocarbamates,

pyrethroids, bipyridyls, and even organochlorines) (10,

24). Therefore, it can be assumed that tomato production systems

located in said region, not yet documented, represent a scenario where farmers

might be highly exposed to pesticides of different toxicity. Considering the

information cited, the present study documents the presence of pests and

diseases on tomato crops, the diversity of pesticides used, and the symptoms

related to acute intoxication due to pesticide exposure, in different regions

of the State of Oaxaca.

Materials

and methods

A descriptive

study was carried out in municipalities from different regions of the State of

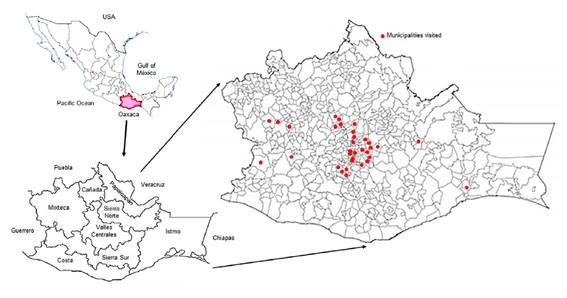

Oaxaca from September 2019 to September 2021 (figure 1).

Figure 1. Study

locations in the State of Oaxaca.

Figura 1. Ubicación

del área de estudio en el estado de Oaxaca.

The study

population included tomato producers residing in the visited sites. Several

field visits identified producers who, by prior authorization and manifesting

pesticide use, completed a survey documenting age and information related to

tomato cultivation (historical time of the crop; pest and disease problems; and

pesticide use), as well as APP symptoms during or after fumigation (2, 11, 12). All individuals were informed of the

study’s objective under the Helsinki Declaration with the approval of the

Institution’s Ethics Committee.

Information

based on producers knowledge, allowed characterization of the insects and

diseases, i.e., no biological collections were taken. Revision of

technical safety sheets based on trade names determined active ingredients,

chemical classification, and type of action (herbicide, insecticide, or

fungicide). The toxicological category (TC) was based on the Federal Commission

for the Protection against Sanitary Risks (COFEPRIS, by its acronym in Spanish)

(5), substantiated by the LD50 expressed

in mg/kg recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), and under the

Official Mexican Standard: NOM-232-SSA1-2009 (19).

Statistics

included frequencies for the qualitative variables and measures of central

tendency and dispersion for quantitative variables. The Student’s t or

Mann-Whitney U test and Pearson’s or Spearman’s Rho correlations were used,

respectively, following normality of data according to Shapiro-Wilk test for

comparison among groups (19 to 50 / >50 years, <1.0 / >1 ha

cultivated, <10 / >10 years of seniority in the activity) and the number

of AI used, and to relate the number of AI used with the number of APP symptoms

and number of pests and diseases. The statistical package used was SPPS v.15.0.

Results

The sample size

was 114 producers: 61.4% were from 26 municipalities in the Valles Centrales

region, 15.8% from four Mixteca municipalities, 10.5% from the Sierra Sur,

10.5% from the Istmo, and 1.8% in two towns in the Sierra Norte. The average

age was 43.8±14.1 years (range =19 to 73 years). The predominance age group was

19 to 50-year-old group (68.9%) followed by the >50-year-old group (31.1%).

The average area cultivated with tomatoes was 1.2±1.4 ha, with areas <1.0 ha

(73.5%) outweighing areas between 1.0 and 5.0 ha (26.5%). The average tomato

cultivation period was 8.8±7.4 years, predominantly producers with <10 years

growing tomatoes without performing crop rotation (78.1%) over producers

between 11 and 34 years old in the same activity (21.9%). According to the

farmers’ perspective, the most common problem is pest and disease attack

(92.1%), followed by economic difficulties (31.6%), lack of training and

technical advice (28.9%), droughts (26.3%), poor quality of irrigation water

(13.2%), low soil fertility (9.6%), floods (3.5%), and excessive winds (0.9%).

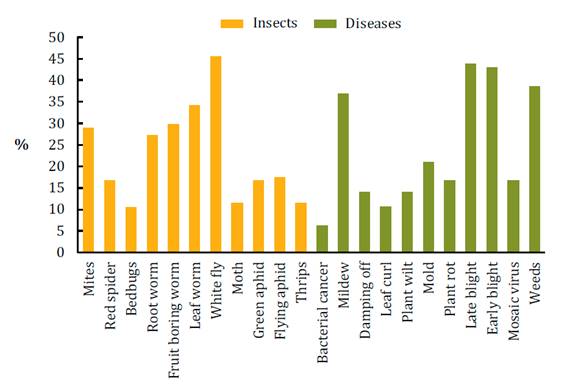

The average attack by insects was 2.5±2.6 of 10 different problems, mainly

white flies and various worms, while for disease development, the media was

2.2±2.3 of 8 identified diseases, mainly blight and mildew. A proportion of

38.6% of the producers stated that weeds must be controlled to guarantee crop

production (figure 2).

Figure 2. Pests

and diseases affecting tomato crops.

Figura 2. Plagas

y enfermedades que afectan al cultivo de tomate.

The average was

5.1±3.2 different types of pests and diseases out of 19 identified; 64% stated

up to five, 28.1% from six to ten, and 6.1% from 11 to 18.

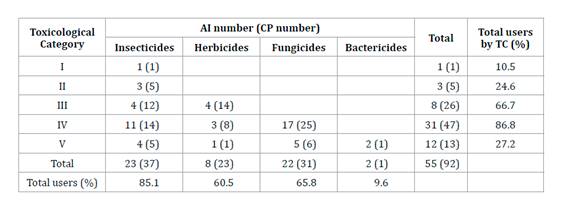

A total of 55

active ingredients (AI) from 92 commercial pesticides were identified,

corresponding to 35 chemical groups. TC IV products predominate, followed by TC

V, III, II, and I. According to their action, insecticides predominate,

followed by fungicides, herbicides, and bactericides. In general, the use of TC

IV insecticides and fungicides and TC III herbicides prevails (table

1).

Table

1. Toxicological category of identified

pesticides via active ingredients (AI) and commercial presentation (CP).

Tabla 1. Categoría

toxicológica de los plaguicidas identificados en el presente estudio, a través

de sus ingredientes activos (IA) y presentación comercial (PC).

When detection

and identification of more pests and diseases occurred, more varieties of AI

were used (Spearman’s Rho=0.202, p=0.031). In addition, there was a significant

increase in AI use on surfaces over 1 ha, compared to smaller áreas

(Mann-Whitney U = 437.5, p = 0.014). Producers with <10 years in tomato

production, used a significantly greater diversity of AI compared to producers

with greater seniority (Mann-Whitney U= 710.5, p=0.005). No significant

differences were identified between age groups and number of AI used. The most

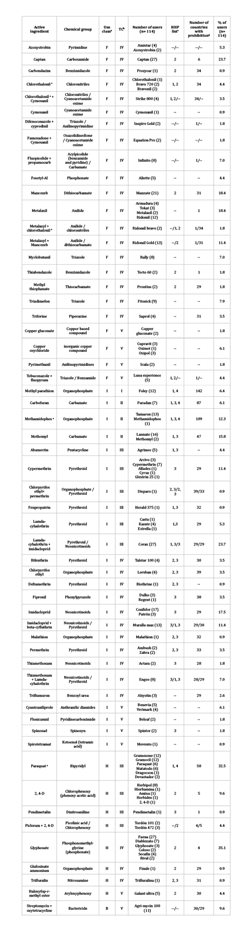

frequently used insecticides were the combination of lamba-cyhalothrin with

imidacloprid by the commercial brand Corax (pyrethroid and neonicotinoid TC

III), imidacloprid by Confidor and Patron, methomyl by Lannate and generic

methomyl (carbamate TC II). A small group of users utilized methyl parathion as

Foley (organophosphate TC I). The most used fungicides were Captan by the same trade

name (carboxamide, TC IV), followed by mancozeb by Manzate brand

(dithiocarbamate, TC IV), metalaxyl by Ridomil mainly (anilide, TC IV), and the

combination of metalaxyl with mancozeb by Ridomil Gold. For herbicides,

glyphosate (phosphonate TC IV) and paraquat (bipyridyl TC III) stand out under

various commercial brands. The bactericides identified were streptomycin in

combination with oxytetracycline under the trade name Agri-mycin 100, used by a

small group (table 2).

Table

2. Classification of identified pesticides

in tomato crops.

Tabla 2. Clasificación

de los plaguicidas identificados en el cultivo de tomate.

H / I / F / B:

Herbicide/Insecticide/Fungicide/Bactericide. b TC:

Toxicological Category: I (extremely dangerous), II (highly dangerous), III (moderately

dangerous), IV (slightly dangerous), and V (normally not dangerous) (5, 19). c Criteria for inclusion in the PAN International Highly

Hazardous Pesticides list: [1] High Acute Toxicity; [2] Chronic effects on

human health; [3] Environmental toxicity; and [4] Restricted or prohibited by

environmental conventions (21). d PAN

International list of prohibited pesticides in other countries (22).

e Use restricted by COFEPRIS

(2022).

a H / I / F / B: Herbicida/Insecticida/Fungicida/Bactericida. b CT: Categoría Toxicológica: I (extremadamente peligroso),

II (altamente peligroso), III (moderadamente peligroso), IV (ligeramente

peligroso), V (normalmente no peligroso) (5,

19). c Criterios de inclusión en la lista

de Plaguicidas Altamente Peligrosos de PAN Internacional: [1] Toxicidad Aguda

alta; [2] Efectos crónicos en la salud humana; [3] Toxicidad ambiental y; [4]

Restringidos o prohibidos por convenios ambientales (21). d Lista

de plaguicidas prohibidos en otros países de PAN Internacional (22).

e Uso restringido por COFEPRIS

(2022).

An average of

3.9±2.3 AI per producer is used, 48.2% use up to three AI, 32.5% from four to

six AI, and 19.3% from seven to nine AI.

Plot average

fumigation time was 2.8±1.8 hours daily. Producers (31.6%) stated having at

least one hour a day exposure, 36.8% up to three hours, and 31.6% up to six

hours. A high diversity of fungicides and insecticides control different

diseases and insects. Triazoles are chosen as fungicides, and pyrethroids,

organophosphates, neonicotinoids, and carbamates, as insecticides. Several

producers (7.9%) used duplicated applications of the same active ingredient via

different commercial products, especially three herbicides (Paraquat: Gramoxone

and generic Paraquat [0.9], Gramoxone and Matatodo [0.9%]; 2, 4-D: Amina and Herbidex [0.9%]; Glyphosate:

Diablozate with Rival [0.9%], Faena and Colossus [0.9%]; Faena with Secafin [2.6%]) and an insecticide (Ciantraniliprol: Benevia and

Verimarck [1.8%]).

In addition, a group of producers applied some pesticide mixed with foliar

fertilizers (17.5%) or other pesticides (7.9%). Three users combined

insecticides (Arrivo with Karate: cypermethrin with lamda-cyhalothrin; Foley

with Engeo: parathion with thiamethoxan+lambda-cyhalothrin; Patron with Lannate:

chlorpyrifos ethyl with methomyl), three users mixed herbicides (Herbipol with

Coloso: 2,4-D with glyphosate; Tordon 101 with Tordon 472: both contain

picloram+2,4-D; Diablozate with Tordon 101: glyphosate with picloram+2,4-D),

one user mixed fungicides (Cymoxanil with Manzate: cymoxanil with mancozeb),

and two users used insecticides with fungicides (Foley -paration- with

fungicides without mentioning their names; Karate with Cymoxanil and Manzate:

lamda-cyhalotrina, cymoxanil, and mancozeb).

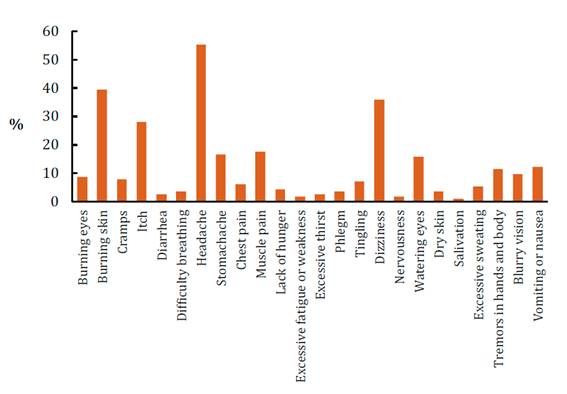

The average number

of APP symptoms in producers was 3.0±2.6 out of 17 identified. While 36.0%

manifested up to three symptoms, 24.6% had four to six symptoms, and 12.3% from

seven to ten symptoms. The symptoms most frequently perceived were headache,

burning skin, dizziness, itching, muscle and stomach pain, and watery eyes, in

that order of occurrence (figure 3).

Figure 3. Symptoms

of acute pesticide poisoning perceived by users.

Figura 3. Síntomas

de intoxicación aguda por plaguicidas percibidas por los usuarios.

The average time

for the symptoms to appear was 5.0±4.5 years, during and after fumigation. No

producer mentioned using personal protection when fumigating. No significant

association was identified between the number of AI and APP symptoms

(Spearman’s Rho=0.066, p=0.488). It should be noted that 27.2% of the users

stated no symptoms.

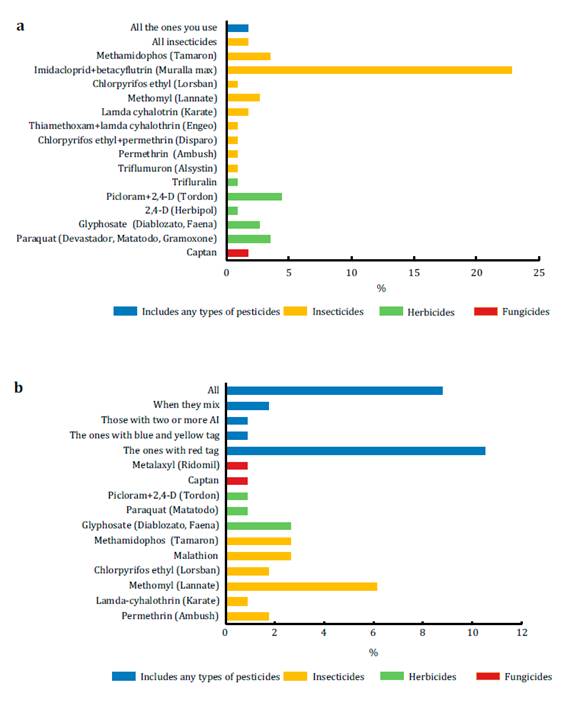

However, 60% of

the users accepted that some pesticides used, cause said symptoms, insecticides

predominating and particularly, imidacloprid in combination with betacyfluthrin,

followed by the herbicides paraquat, picloram+2, 4-D, methamidophos, methomyl,

and glyphosate mainly (figure 4a).

Figure 4. a-

Active ingredients perceived as responsible for APP symptoms, and b- Active

ingredients identified as the most dangerous.

Figura 4. a-

Ingredientes activos percibidos como los responsables de los síntomas de IAP y,

b- Ingredientes activos identificados como los más peligrosos por los usuarios.

A small group of

users stated all insecticides and/or pesticides used, cause their perceived

symptoms. In addition, 44.7% of the producers affirmed that red-labeled

products and insecticide and herbicide types are the most dangerous and toxic,

with methomyl and glyphosate predominating in the latter groups, respectively (figure 4b). Nine users (7.9%) agreed that the same AI

responsible for APP are the most dangerous and toxic. The products were

permethrin (Ambush), glyphosate (Diablozato and Faena), lamda-cyhalothrin

(Karate), methomyl (Lannate), chlorpyrifos ethyl (Lorsban), and methamidophos

(Tamaron), mainly belonging to neonicotinoids, pyrethroids, bipyridyl,

organophosphates, and carbamates.

Discussion

Tomatoes are one

highly demanded vegetable in the Mexican national market, and the State of

Oaxaca is no exception. This high demand for tomatoes is explained by the need

to be met in the Valles Centrales region, which is home to 33% of the state

population in 121 municipalities, and in particular, in the metropolitan area,

where 17.7% of the total population resides, and distributed in 23

municipalities. The identification of a significant number of young producers

in the Valles Centrales region coincides with this increased demand for tomato

production (29). The increased economic

opportunity is attractive for new producers. However, farmers face various

problems, some of which coincide with what has been reported in other studies,

where climate change, pests, and diseases negatively affect vegetable

productivity, including tomatoes, worldwide (15).

In particular, early blight and powdery mildew cause the most damage in the

South of Tamaulipas (27) and Sinaloa,

Mexico (8). Insects, such as white flies

and various worms cause severe damage in multiple provinces of Ecuador (4) and in the Ivory Coast, Africa (31). This reaffirms that tomatoes are susceptible

to a variety of insects and diseases (25),

that if not prevented and/or controlled, cause substantial yield losses and

severe economic impacts.

The present

study identified a significant association between using high diversity AI

against a greater number of pests and diseases, in areas >1 ha, and

producers with <10 years of experience. These findings are similar to those

reported for Los Altos de Chiapas, Mexico (1),

where increased pesticide use was found in the largest agricultural áreas with

the highest diversity of pests and diseases. Recently incorporated producers

use a greater variety of AI to obtain the highest possible agricultural yields

and guarantee investment returns, coinciding with what was reported for Loja,

Ecuador (3). These facts indicate

similarities in the circulation and use of various AI in Mexico and South

America. In addition, there is evident abuse in the application of various

pesticides individually and in mixtures, as occurs in other similar production

systems in India (13) and Ghana (6). Concerning mixtures, underreporting of

pesticide application is likely due to fear of sharing which mixtures they

consider more successful in preventing or controlling pests and diseases. It is

essential to mention that several non-COFEPRIS (2022),

recorded insecticides were identified (Glextrin 25, Casta, Estrella, and

Alsystin), probably because they are not yet registered or being sold

clandestinely in the state.

It is alarming

that 58.2% of the AI identified are considered Highly Hazardous Pesticides,

fungicides, and herbicides due to their chronic effects on human health, while

most commonly used insecticides in this group are included in the list mainly

because of their environmental toxicity. In addition, 67.3% of AI are

prohibited in other countries due to their high acute and environmental

toxicity including possible chronic health effects (21,

22). However, the fungicide chlorothalonil, the insecticide

methamidophos, and the herbicide paraquat are considered restricted pesticides

in Mexico by COFEPRIS (2022) and a recent campaign

promotes the gradual elimination of glyphosate by a presidential decree

published on December 31, 2020 (7).

Unfortunately, in the agricultural fields of the Mexican southeast, this

chemical is still being used.

Regarding APP

symptoms, 27.2% of producers stated not having any. However, it is likely they

hide their symptoms, since it is common among the rural male population to

project they are strong and perceive themselves as immune to the dangers that

APP represents (14). Several identified

APP symptoms are reported when users are exposed to acetylcholinesterase

inhibitors (muscarinic and nicotinic), such as carbamates and organophosphates

(34). Health damage from exposure via inhalation

during fumigation is exhibited mainly through symptoms related to the central

nervous system. Dermal exposure damage is seen by skin irritation given absent

personal protection while fumigating. The presence of weakness, headache,

dizziness, fever, and skin irritation have been reported with the use of

pyrethroids and carbamates mainly in small tomato producers in Cameroon (30), as well as in Arusha, Northern Tanzania (17), similar to the findings obtained in this

study.

A considerable

proportion of producers have shown three or more APP symptoms. Although no

clinical tests were used to detect residues or metabolites of the identified

pesticides, one or several pesticides used are possibly responsible for their

symptoms. The high variety of commercial products applied individually or mixed

complicates AI accurate identification concerning APP symptoms. Even though

most of the AI used belong to fungicides and insecticides of TC IV and V,

considered by Mexican regulations as only dangerous and not harmful, they still

harm human health and the environment causing potential latent health risk

among producers chronically exposed to these pesticides, as well as health

risks to consumers, since residual pesticide contamination in food has been

documented. Such is the case for the presence of pyrethroid insecticides

lambda-cyhalothrin, cypermethrin, and deltamethrin, as well as the

organophosphate chlorpyrifos on tomato surfaces (20).

In this regard, acute poisoning due to intake of contaminated food is not frequent.

However, daily consumption may lead to diseases manifesting in the long term,

such as various types of cancers (18),

implying a public health problem.

Despite the

limitation of the sample size, this study provides information for governmental

and non-governmental agencies in the agricultural sector to propose actions

addressing this problem. For example, proper training in the use and management

of pesticides is highly recommended. In addition, personal protection during

pesticide application is strongly recommended. It is also advisable to carry

out periodic phytosanitary diagnoses, establishing better control techniques,

along with gradual replacement of pesticides with more environmentally friendly

products. Taking this a step further, promoting agroecological practices (like

crop rotation, use of plant extracts and allelopathic plants, among others) (23), guarantees healthier plants, and promotes a

safer work environment and more nutritious food for the consumer.

Pesticide-residue monitoring in the harvested product, water, and soil, as well

as in users and consumers, helps identify possible risks to public health and

the environment.

Conclusions

Younger

producers are introducing themselves to tomato cultivation under a conventional

system with the intensive use of various pesticides, predominantly TC IV

insecticides and fungicides, as well as TC III herbicides. Primary damages to

tomato crops are due to white flies, multiple worms, blight, mildew, and weeds.

In the short period of conventional agriculture, increasing pests and diseases

in areas >1 ha is associated with using a greater variety of pesticides.

Most producers had up to six APP symptoms, related to organophosphates and

carbamates, and predominantly to the central nervous system and skin. However,

the possibility that several symptoms are related to other chemical groups has

not been ruled out. Pesticide use will likely continue in the area studied,

thus, in the medium to long term, health damages associated with acute and

chronic exposure to the pesticides identified will continue. We recommend

promoting the adoption of agroecological practices, providing training in the

proper use and management of pesticides, and gradual substitution with less

aggressive products.

1. Bernardino,

H. H. U.; Mariaca, M. R.; Nazar, B. A.; Álvarez, S. J. D.; Torres, D. A.;

Herrera, P. C. 2016. Factores socioeconómicos y tecnológicos en el uso de

agroquímicos en tres sistemas agrícolas en Los Altos de Chiapas, México.

Revista Interciencia. 41(6): 382-392.

http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=33945816003

2. Bernardino,

H. H. U.; Mariaca, M. R.; Nazar, B. A.; Álvarez, S. J. D.; Torres, D. A.;

Herrera, P.C. 2019. Conocimientos, conductas y síntomas de intoxicación aguda

por plaguicidas entre productores de tres sistemas de producción agrícolas en

los Altos de Chiapas, México. Rev. Int. Contam. Ambie. 35(1): 7-23.

doi:10.20937/RICA.2019.35.01.01

3.

Castillo-Pérez, B.; Castillo-Bermeo, V. 2021. Uso de plaguicidas químicos en

tomate riñón (Solanum lycopersicum L.) en condiciones de invernadero y

campo en Loja, Ecuador. CEDAMAZ Revista del Centro de Estudio y Desarrollo de

la Amazonia. 11(1): 22-41. https://revistas.

unl.edu.ec/index.php/cedamaz/article/view/1034

4. Chirinos, D.

T.; Castro, R.; Cun, J.; Castro, J.; Peñarrieta, B. S.; Solis, L.;

Geraud-Pouey, F. 2020. Los insecticidas y el control de plagas agrícolas: la

magnitud de su uso en cultivos de algunas provincias de Ecuador. Ciencia y

Tecnología Agropecuaria. 21(1): e1276. doi: https://doi.org/10.21930/rcta.vol21_num1_art:1276

5. Comisión

Federal para la Protección contra Riesgos Sanitarios (COFEPRIS). 2022. Consulta

de registros sanitarios de plaguicidas, nutrientes vegetales y LMR. México:

COFEPRIS, Secretaria de Salud. http://siipris03.cofepris.gob.mx/Resoluciones/

Consultas/ConWebRegPlaguicida.asp, (consultation date: 12/06/2022).

6. Dari, L.;

Addo, A.; Dzisi, K. A. 2016. Pesticide use in the production of tomato (Solanum

lycopersicum L.) in some areas of Northern Ghana. African Journal of

Agricultural Research. 11(5): 352-355. doi:10.5897/AJAR2015.10325

7. Diario

Oficial de la Federación. 2020. Secretaria de Gobernación. México.

https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.

php?codigo=5609365&fecha=31/12/2020#gsc.tab=0, (consultation date a:16/09/2022).

8.

Félix-Gastélum, R.; Maldonado-Mendoza, I. E.; Beltrán-Peña, H.;

Apodaca-Sánchez, M. A.; Espinoza-Matías, S.; Martínez-Valenzuela, M. C.;

Longoria-Espinoza, R. M.; Olivas-Peraza, N. G. 2017. Powdery mildews in

agricultural crops of Sinaloa: Current status on their identification and

future research lines. Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología. 35: 106-129.

https://doi.org/10.18781/r.mex.fit.1607-4

9. Fideicomisos

Instituidos en Relación a la Agricultura (FIRA). 2019. Panorama agroalimentario.

Tomate rojo 2019. Dirección de Investigación y Evaluación Económica y

Sectorial. México.

https://www.inforural.com.mx/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Panorama-Agroalimentario-Tomate-rojo-2019.pdf

10. García, G.

C.; Rodríguez, M. G. D. 2012. Problemática y riesgo ambiental por el uso de

plaguicidas en Sinaloa. Ra Ximhai. 8(3): 1-10. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=46125177005

11. Jensen, H.

K.; Konradsen, F.; Jørs, E.; Petersen, J. H.; Dalsgaard, A. 2011. Pesticide use

and self-reported symptoms of acute pesticide poisoning among aquatic farmers

in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Journal of Toxicology. 8. doi:10.1155/2011/639814

12.

Kangkhetkron, T.; Juntarawijit, C. 2012. Factors influencing practice of

pesticide use and acute health symptoms among farmers in Nakhon Sawan,

Thailand. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(16): 8803. doi:10.3390/ijerph18168803

13.

Keshavareddy, G.; Nagaraj, K. H.; Kamala, B. S.; Kulkarni, L. R. 2018.

Pesticides usage and handling by the tomato growers in Ramanagara District of

Karnataka, India-An Analysis. International Journal of Current Microbiology and

Applied Sciences. 7(4): 3312-3321. https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2018.704.375

14. Kunin, J.;

Aldana, L. P. 2020. Percepción social del riesgo y dinámicas de género en la

producción agrícola basada en plaguicidas en la Pampa Húmeda Argentina.

Sexualidad, Salud y Sociedad. Revista Latinoamericana. 35: 58-81.

http://doi.org/10.1590/1984-6487. sess.2020.35.04.a

15. Litskas, V.

D.; Migeon, A.; Navajas, M.; Tixier, M. S.; Stavrinides, M. C. 2019. Impacts of

climate change on tomato, a notorious pest and its natural enemy: small scale

agriculture at higher risk. Environmental Research Letters. 14(8): 1-9.

https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab3313

16. Liu, J.;

Wang, X. 2020. Tomato diseases and pests detection based on improved Yolo V3

convolutional neural network. Front Plant Sci. 11: 898.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00898

17. Manyilizu,

W. B.; Mdegela, R. H.; Helleve, A.; Skjerve, E.; Kazwala, R.; Nonga, H.;

Muller, M. H. B.; Lie, E.; Lyche, J. 2017. Self-reported symptoms and pesticide

use among arm workers in Arusha, Northern Tanzania: A cross sectional study.

Toxics. 5(4): 24. doi: 10.3390/ toxics5040024

18. Morera, R.

I. 2015. Identificación de principios activos de plaguicidas en frutas,

hortalizas y granos básicos en Costa Rica: Una propuesta para la implementación

de nuevas metodologías de análisis. Revista Pensamiento Actual. 15(25):

155-171. https://revistas.ucr.

ac.cr/index.php/pensamiento-actual/article/view/22602/24026

19. Norma

Oficial Mexicana NOM-232-SSA1-2009. Diario Oficial de la Federación. Publicado

el 13 de abril de 2010. https://www.gob.mx/cofepris/documentos/nom-232-ssa1-2009-plaguicidas,

(consultation date: 3/06/2022).

20. Páez, M. M.

I.; Varona, U. M.; Díaz, S. M.; Castro, R. A.; Barbosa, E.; Carvajal, N.;

Londoño, A. 2011. Evaluación de riesgo en humanos por plaguicidas en tomate

cultivado con sistemas tradicional y BPA (Buenas Prácticas Agrícolas). Revista

de Ciencias Sociales. 15: 153-166. https://doi.org/10.25100/rc.v15i0.523

21. Pan

International. 2021. List of Highly Hazardous Pesticides. March 2021. Pesticide

Action Network International c/o PAN International, Hamburg, Germany. https://

pan-international.org/wp-content/uploads/PAN_HHP_List-es.pdf, (consultation date:

12/04/2022).

22. Pan

International. 2022. PAN International Consolidated List of Baned Pesticide.

2022. Pesticide Action Network International c/o PAN International c/o PAN Asia

Pacific, Penang, Malaysia. 6th edition. https://pan-international.org/pan-international-consolidated-list-of-bannedpesticides/,

(consultation date: 12/04/2022).

23. Peredo, P.

S.; Barrera, S. C. 2019. Evaluación participativa de la sustentabilidad entre

un sistema campesino bajo manejo convencional y uno agroecológico de una comunidad

Mapuche de la Región de la Araucanía (Chile). Revista de la Facultad de

Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 51(1):

323-336.

https://revistas.uncu.edu.ar/ojs3/index.php/RFCA/article/view/2454/1777

24. Pérez, M.

A.; Navarro, H.; Miranda, E. 2013. Residuos de plaguicidas en hortalizas:

problemática y riesgo en México. Rev. Int. Contam. Ambie . 29 (Número

especial sobre plaguicidas): 45-64. https://www.revistascca.unam.mx/rica/index.php/rica/article/view/41423

25. Reinoso, J.

2015. Diagnóstico del uso de plaguicidas en el cultivo de tomate riñón en el

Cantón Paute. Maskana. 6(2):147-154. https://doi.org/10.18537/mskn.06.02.11

26. Rodríguez,

B. M. K.; Zavaleta, D.; Reyes, V. L.; Torres, A. H.; Bernardino, H. H. U. 2020.

Uso de plaguicidas e intoxicaciones agudas en la población rural de San

Baltazar Chichicápam, Oaxaca, México. Revista AIDIS-UNAM. 13(2): 616-629.

http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/iingen.0718378xe.2020.13.2.68117

27. Salas, G. A.

L.; Osorio, H. E.; Espinoza, A. C. A.; Rodríguez, H. R.; Segura, M. M. T. J.;

Neri, R. E.; Estrada, D. B. 2022. Principales enfermedades del cultivo de

tomate (Solanum lycopersicum L.) en condiciones de campo. Ciencia Latina

Revista Científica Multidisciplinar. 6(1): 1-21. https://doi.org/10.37811/cl_rcm.v6i1.1793

28.

Schreinemachers, P.; Simmons, E. B.; Wopereis, M. C. S. 2018. Tapping the

economic and nutritional power of vegetables. Global Food Security. 16: 36-45.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2017.09.005

29. Sistema de Información

Agroalimentaria y Pesquera. 2021. Producción anual agrícola. Sistema de Información

Agroalimentaria y Pesquera (SIAP). Gobierno de México.

https://www.gob.mx/siap/documentos/siacon-ng-161430 y https://nube.siap.gob.mx/

avance_agricol/, (consultation date: 14/07/2022).

30. Tandi, T.;

Wook, C.; Shendeh, T.; Eko, E.; Afoh, C. 2014. Small-scale tomato cultivators’

perception on pesticides usage and practices in Buea Cameroon. Health. 6:

2945-2958. doi: 10.4236/health.2014.621333

31. Tonessia, D.

C.; Soumahin, E. F.; Boye, M. A. D.; Niangoran, Y. A. T.; Djabla, J. M.; Zoh,

O. D.; Kouadio, Y. J. 2018. Diseases and pests associated to tomato cultivation

in the locality of Daloa (Côte d’Ivoire). Journal of Advances in Agriculture.

9: 1546-1557. doi:10.24297/jaa.v9i0.7935

32. Tudi, M.;

Ruan, D. H.; Wang, L.; Lyu, J.; Sadler, R.; Connell, D.; Chu, C.; Phung, D.T.

2021. Agriculture development, pesticide application and its impact on the

environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18: 1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031112

33. Umetsu, N.;

Shirai, Y. 2020. Development of novel pesticides in the 21st century. Journal

of Pesticide Science. 45(2): 54-74. doi:

10.1584/jpestics.D20-201

34. Virú, L. M.

A. 2015. Manejo actual de las intoxicaciones agudas por inhibidores de la

colinesterasa: conceptos erróneos y necesidad de guías peruanas actualizadas.

Anales de la Facultad de Medicina. 76(4): 431-437.

http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/anales.v76i4.11414