Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 56(1). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2024.

Original article

Traditional

cow-calf systems of the northern region of Santa Fe, Argentina: current

situation and improvement opportunities

Sistemas

de cría tradicionales de la región norte de Santa Fe, Argentina: situación

actual y oportunidades de mejora

Javier Baudracco2,

Carlos Dimundo1,

Belén Lazzarini1,

Julieta Scarel3,

Agustín Alesso2,

Claudio Machado4

1Universidad

Nacional del Litoral. Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. R.P. Kreder 2805 2° Piso.

C. P. 3080. Esperanza. Argentina.

2Universidad

Nacional del Litoral. FCA. CONICET. IciAgro Litoral. R. P. Kreder 2805. C. P.

3080. Esperanza. Argentina.

3Instituto

Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria. Agencia de Extensión Rural INTA Calchaquí.

Bv. Belgrano 939. C. P. 3050. Calchaquí. Argentina.

4Facultad

de Ciencias Veterinarias. Centro de Investigación Veterinaria de

Tandil-CIVETAN. CICPBA-CONICET, PROANVET UNCPBA. B7000GHG. Tandil. Argentina.

*guillerminagregoretti.gg@gmail.com

Abstract

Cow-calf systems

are at the core of Argentina´s significant national beef industry. The objectives

were: i) to characterize the productive state of traditional cow-calf systems, named

BASE, from the northern region of Santa Fe province, ii) to identify

technologies for the productive improvement of the BASE system, and iii) to

quantify the productive and economic impact of the adoption of the identified

technologies. To characterize the BASE system, the available published data

were systematized and validated in a workshop with leading regional experts in

the field. To identify the technologies for improvement, a survey was conducted

among regional farm advisors. Finally, to quantify the impact of adopting

improvements in the BASE system, a modelling study was conducted. The results showed

that traditional cow-calf systems have low productive and reproductive

efficiency (45 kg LW ha-1 year-1 and 48% weaning rate)

and little adoption of herd management and forage production technologies. The

technologies identified were grazing management, training of farmers and farm

staff, and seasonal mating. The modelling study showed that improvements in the

production and use of forage and herd management practices would increase beef

production and the gross margin of the BASE system by 70% and 96%,

respectively.

Keywords: beef production,

survey, technologies, simulation, opportunities

Resumen

Los sistemas de

cría son el núcleo de la importante industria nacional de carne bovina de

Argentina. Los objetivos fueron: i) caracterizar la situación productiva de

sistemas de cría tradicionales, nombrado BASE, del norte de la provincia de

Santa Fe ii) identificar tecnologías para su mejora productiva iii) cuantificar

el impacto productivo y económico de la adopción de las tecnologías

identificadas. Para caracterizar el sistema BASE se sistematizó la información

disponible que fue validada en un taller con expertos referentes de la zona.

Para identificar tecnologías de mejora, se implementó una encuesta a asesores

referentes de la región. Finalmente, para cuantificar el impacto de la adopción

de mejoras en el sistema BASE se realizó un estudio de simulación. Los

resultados demostraron que los sistemas de cría tradicionales tienen baja

eficiencia productiva y reproductiva (45 kg de PV ha-1 año-1

y 48% de destete, respectivamente) y baja adopción de tecnologías de manejo del

rodeo y producción forrajera. Las tecnologías identificadas fueron manejo del

pastoreo, capacitación del productor y el personal de campo y estacionamiento

del servicio. La simulación demostró que mejoras en producción y uso de

forrajes y manejo de rodeo podrían incrementar la producción de carne y el

margen bruto del sistema BASE en un 70% y 96%, respectivamente.

Palabras claves:

producción

de carne, encuesta, tecnologías, simulación, oportunidades

Originales: Recepción: 12/04/2023 - Aceptación: 29/02/2024

Introduction

The livestock

sector faces the challenge of producing food in the context of increasing global

demand for meat, which is estimated to increase by 1.6% per year (30). Intensification has been a way to improve

productivity and efficiency in the beef production sector and has contributed

to an increase in food production since the mid-twentieth century (18, 38). Intensification of livestock systems is

defined as an increase in meat and milk production per animal and per area of

land (31). In beef production systems,

there are mainly two ways of intensification: through the increase in pasture

production and supplementation of animals in grazing systems, or through the

confinement of animals in feedlots with high feed offers (20).

Argentina

produces 3.1 thousand tonnes of beef and ranks fourth among the world’s beef-producing

and exporting countries (43). Beef

production is a relevant activity for the country’s economy because it

contributes 28.7% of gross domestic income and 11% of private employment within

the agricultural industry (14). However,

the national average weaning rate (total of weaned calves/ total of cows × 100)

is lower (63%) (26) than that in other

beef-producing countries such as Australia (70%) (41)

and New Zealand (80%) (42). In Argentina,

more than 95% of the area used for cow-calf systems is based on natural grasslands

(non-cultivated environments), with poor synchronization between forage supply

and livestock nutrient demand, reduced control of animal diseases (15), mainly concerning venereal and reproductive

diseases (2), and low stocking rates

(less than 0.50 cow ha-1) (26),

resulting in low productivity, in terms of beef production per hectare (less

than 90 kg ha-1) (26).

Buenos Aires

province is the main beef-producing region of Argentina, and different studies

have evaluated the impact of technological improvements (3, 16), technical assistance on the productivity

of systems (33), and pasture production (22), among others. However, for the second most

important region in calves´ provision, the northern region of Santa Fe

province, which provides 10% of total Argentine calves (26), there is minimal information regarding the

characterization of technified systems (21),

but none for traditional systems. Therefore, the objectives of the present

study were: i) to characterize the productive situation of the traditional

cow-calf systems (hereafter BASE system) in the northern region of Santa Fe

province, Argentina; ii) to identify technologies for improving productivity

based on critical technologies; and iii) to quantify the productive and

economic impacts of applying technologies.

Materials

and methods

Description

of the region

The cow-calf

systems analysed in this study are located in the north-central region of

Argentina, between 28° to 30° South and 59° to 60° West in the departments of

General Obligado and Vera in the province of Santa Fe. This region has

approximately 900,000 ha of agricultural use (10).

The climate is subtropical with average, minimum, and maximum annual air

temperature of 20.1°C, 10.1°C (July) and 28.2°C (January), respectively (23). The average annual rainfall (±SD) (over the

last 50 years) is 1,294 ± 310 mm, concentrated in the warmest season (82%

between October and April) (24).

Predominant soils belong to the Natracualf and Alfacualf groups, with drainage

deficiency and saline-sodium conditions (19).

Productive

characterization of the traditional systems

Different

sources of information (scientific literature, technical reports, national and

regional statistics and a workshop with local experts) were used to

characterize the traditional (BASE) system in terms of land use, herd

management, forage production, and productive efficiency indicators such as

stocking rate (cows ha-1), weaning rate (%), and beef production (kg

of calves beef ha-1 year-1 and kg of LW ha-1

year-1).

Survey

design: Identification and ranking of technologies to improve productivity

A digital survey

(Google Forms) was designed to identify and rank technologies that could

promote the improvement of traditional systems. The project’s interdisciplinary

team identified most region-based farm advisors and extensionists with

recognized expertise in the field (n = 22) and invited them to complete the

survey. The survey was structured into 10 questions. Questions 1 to 6 refer to

the degree of agreement that advisors had regarding the priority of

improvements in forage resources, herd management, productive and economic

records, and farm infrastructure. Questions 7 to 10 refer to the technologies

that advisors prioritize to improve forage resources, herd management, and farm

infrastructure. To analyze the results, radar charts were created with the

average priority for each option. The prioritization patterns for each question

were analyzed using principal components analysis. In addition, the

relationship between the prioritizations assigned according to expertise

background (agriculture or veterinary science) and work environment (private or

public) of the respondents was evaluated using ANOVA. Infostat software version

2018 (12) was used for statistical

analyses.

Simulation of

productive and economic impact of applying technologies

1- Simulation

model: The productive and economic impact of the adoption of the identified

technologies in the survey described above was quantified through a

participatory modelling approach (17)

using Baqueano Cría software (40). This

deterministic simulation model represents stabilized cow-calf systems and

allows for monthly estimations of herd dynamics, forage and energy balance

between feed supply and animal requirements, and productive and economic

results. The main inputs of this model include herd composition, prices and

live weight of cattle categories, monthly availability of forage, and prices of

the main inputs (food, health, and labour). The main outputs included beef

production (kg LW ha-1 year-1) and gross margin (U$S ha-1).

2- Simulation of

BASE and improved systems: The traditional cow-calf systems, characterized in

the present study (objective i) and named as BASE system, were first simulated.

It was used as the baseline to simulate three further scenarios, using

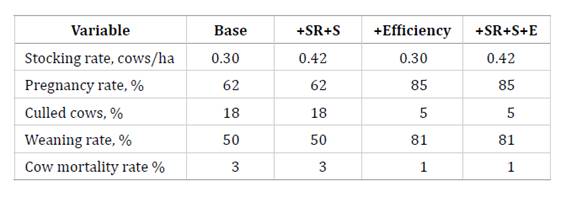

technologies to improve productivity and economic results (improved systems) (table 1).

Table

1. Characteristics of the BASE system and

improved systems include: increased stocking rate (+SR), increased reproductive

efficiency (+EFFICIENCY) and the combination of both alternatives (+SR+E).

Tabla 1. Características

del sistema BASE y sistemas mejorados incluyendo: aumento de carga animal

(+SR), aumento de la eficiencia reproductiva (+EFFICIENCY) y la combinación de

ambas alternativas (+SR+E).

Based on the

technologies identified as critical by the experts (objective ii of this

study), three improved systems were designed (table 1):

+SR+S, which includes increased stocking rate and supplementation with hay

(+39% SR and +173% of hay than the BASE), +EFFICIENCY, which includes higher

pregnancy rates and lower mortality rates in cows and calves; and finally

+SR+S+E system was simulated, which combined the alternatives +SR+S and

+EFFICIENCY. It was assumed that the greater pregnancy efficiency was the

result of strategic supplementation (2.5 kg of DM of cottonseed and 1 kg of DM

sorghum seed cow -1 d -1 between May and September) due

to its incidence on the body condition of cows (35),

and mortality rates were reduced due to better health management, with greater

expenses on cow health (+77% compared to BASE).

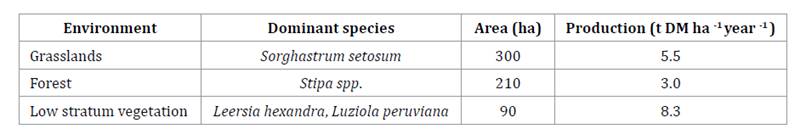

3- Productive

and economic assumptions: Forage production and utilization for the BASE system

were obtained from the database reviewed for objective (i) of this study (table 2), and the same figures were assumed for the improved

systems. The mating season was assumed to occur from November to February for

all systems.

Table

2. Average forage production (Tn DM ha-1

year -1) of the traditional cow-calf system of the northern region

of Santa Fe province.

Tabla 2. Valores

de producción (Tn MS ha-1 año-1) de los recursos

forrajeros de los sistemas de cría tradicionales del norte de la provincia de

Santa Fe.

Economic values

are expressed in U.S. dollars (U$S dollars). A cost of US$ 16 cow -1

was assumed for animal health. Full-time employees were considered for all farm

tasks (180 cows), with a monthly salary of US$744. Herd live weights and farm

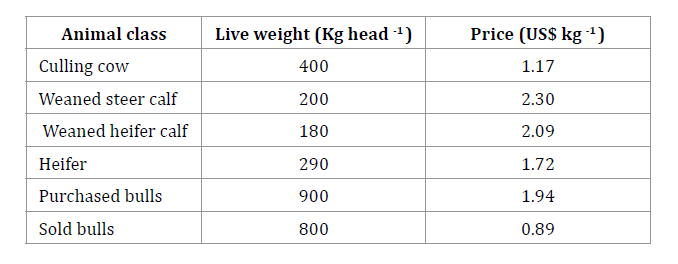

prices are listed in table 3.

Table

3. Herd live weight (kg head-1)

and farm price (U$S kg-1) of different animal categories in a

cow-calf system in the northern region of Santa Fe province.

Tabla 3. Peso

(kg cabeza-1) y precio (U$S kg-1) de las diferentes

categorías en un sistema de cría bovina de la región norte de la provincia de

Santa Fe.

The purchase and

sale expenses of the different animal categories were 5% and 2% of the price,

respectively. The annual gross margin, defined as the difference between net

income and direct costs (1), was also simulated, considering the

prices of the main products for the region (feed, health, and labour).

Results

and discussion

Productive

characterization of the traditional cow-calf system in northern región of Santa

Fe

Use of area

and forage resources

Three

contrasting vegetation environments were differentiated in the region:

grasslands, forests, and low-stratum vegetation (27).

Such environments are usually found in each farm in proportions of 50%, 35%,

and 15% of the total area, respectively (11).

The aforementioned diversity of environments poses a challenge for livestock

management as they have different herbage mass rates, which implies different

grazing management in each environment.

1- Grasslands:

It is defined as plant communities dominated by various species where it

predominates Sorghastrum setosum (Grise.) Hitchc (5, 34). The forage contribution to livestock in

these environments varies from 3,000 to 6,000 kg DM ha-1. Other

species with high forage value, such as legumes (i.e., genus Desmodium,

Desmanthus, and Vicia) and grasses of the genus Paspalum (5), can be found in this environment.

2- Forest: The

predominant species in this environment was Schinopsis balansae Engl.

Plant communities in the forest are dominated by species of the genera Stipa

and Piptochaetium (28). These

environments provide forage for cattle in variable quantities and quality

(1,000-5,000 kg MS ha-1) according to the state of forest

conservation.

3- Low stratum

vegetation: These environments are dominated by hygrophilous herbaceous

communities dominated by grasses such as Echinochloa helodes (Hackel) Parodi,

Leersia hexandra Sw., and Luziola peruviana Juss. Ex J.F. Gmel.,

with a dry matter production of 6,000 to 8,000 kg ha-1 (34).

Improvement of

forage production through fertilization or introduction of cultivated species

such as perennial pastures or annual forage crops is almost null among the

traditional farms in the northern region of Santa Fe province. Cultivated

forage species are usually no more than 2% of total area in cow-calf systems

some cultivated species are Avena sativa L., Melilotus albus Medik,

Medicago sativa L., Sorghum bicolor L. Monech and Chloris

gayana Kunth (6).

Productive

and reproductive efficiency and herd management

Mating is

continuous throughout the year, with little adoption of herd management and

health technologies, such as venereal disease control (13). The age at the first mating is usually

greater than 24 months. Supplementation of heifers is carried out occasionally with

pasture hay (less than 1 kg DM animal-1) in winter and, to a lesser

extent, energy concentrates, such as corn and sorghum grains (6). Calve weaning is performed at 8 months of

age, the weaning rate is 48%, and beef production is approximately 45 kg LW ha-1

year-1 (6).

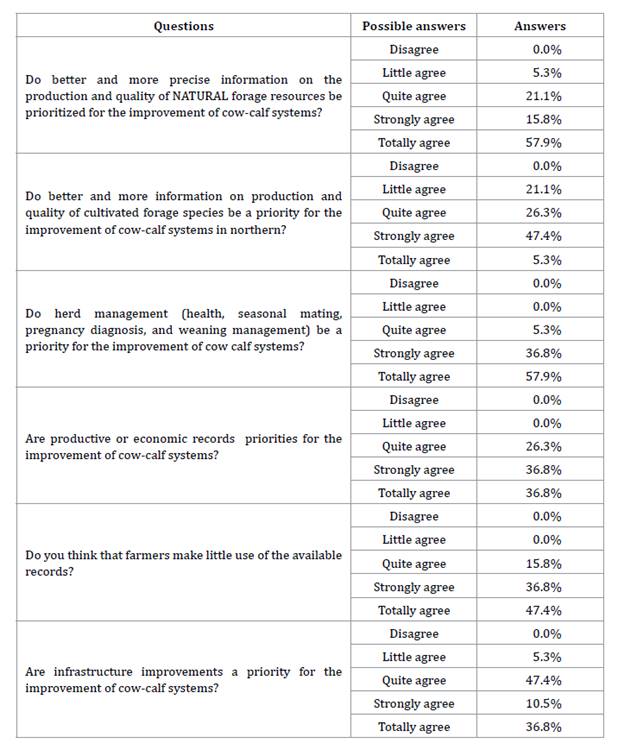

Survey

results: opportunities for technological improvement

There was a high

level of answers (86% of the invited regional consultants). Respondents were

highly experienced experts in veterinary sciences (42%) and agriculture science

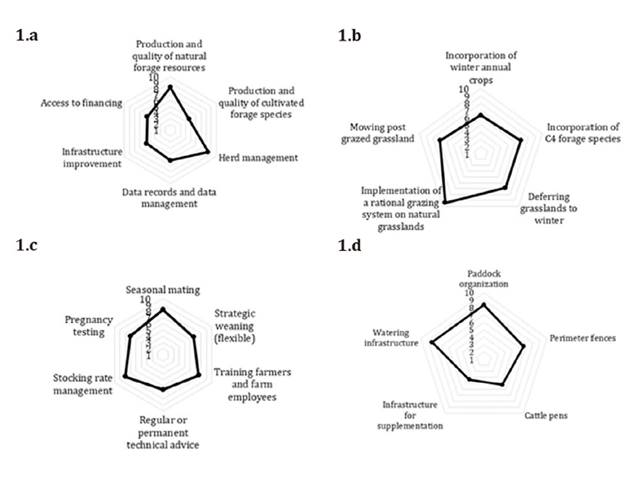

(58%). The results are presented in table 4 and figure

1.

Table

4. Questions 1 to 6 used in the survey to

regional farm advisors and answers.

Tabla 4. Preguntas

utilizadas en la encuesta a asesores referentes y respuestas.

Priority in: (1.b.) forage supply, (1.c.) herd

management, (1.d) infrastructure.

Prioridad en: (1.b.) oferta forrajera, (1.c.) manejo

del rodeo, (1.d.) infraestructura.

Figure 1. Technologies

prioritized by advisors, (10 maximum, 1 minimum). (1.a.) Priority of potential

technological improvements.

Figura 1. Tecnologías

priorizadas por los asesores, (10 máximo, 1 mínimo). (1.a.) Prioridad de

mejoras tecnológicas potenciales.

Priority given

to improve herd management was higher for professionals working in the private sector

(p < 0.05), and in general, answers for each aspect (forage supply, herd

management practices, and farm infrastructure) were independent of the career

and the field of work of the respondents (p > 0.05).

Productive

and economic impact of technological improvements

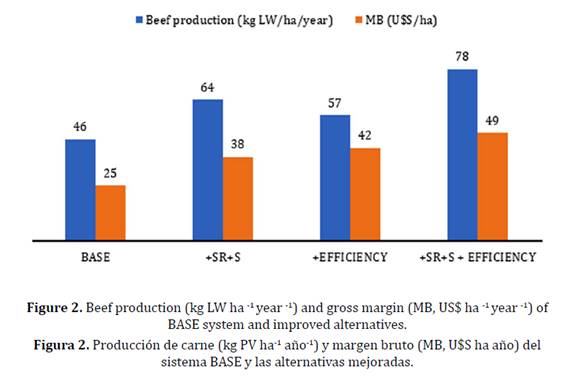

The results of

the modelling studies are shown in figure 2.

Figure 2. Beef

production (kg LW ha-1 year-1) and gross margin (MB, US$

ha-1 year-1) of BASE system and improved alternatives.

Figura 2. Producción

de carne (kg PV ha-1 año-1) y margen bruto (MB, U$S ha-1

año-1) del sistema BASE y las alternativas mejoradas.

All three

improved systems resulted in higher beef production and a higher gross margin

than those of the BASE system. The +SR+S+E alternative showed an increase of

70% and 96% in beef production and gross margin, respectively, compared with

the BASE system, despite showing higher direct costs (figure 2).

These results agree with previous simulation studies (16, 17) conducted in other regions of Argentina,

which showed that the combination of increased SR increased supplementation,

and better reproductive management (similar to +SR+S+E in this study) would

increase productive and economic results to a greater extent than if they are

implemented as sole alternatives.

A change in

stocking rate directly influences income as it correlates with the growth of livestock

capital. However, it’s essential to note that the economic efficiency of

agricultural systems can be significantly influenced by factors beyond the

scope of this study, such as the land tenure regime (39).

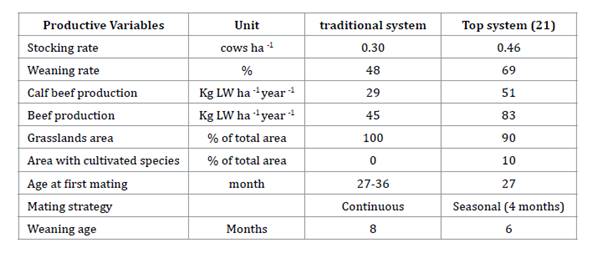

Table

5 shows previous studies and compares the contrasting productive parameters

between the traditional system and existing top technological systems (high use

of technologies) in the same region (21).

Table

5. Productive differences between the

traditional and top cow-calf systems of the northern region of Santa Fe

province.

Tabla 5. Diferencias

productivas entre sistemas tradicionales y tecnificados de la región norte de

la provincia de Santa Fe.

The productive

potential of current top cow-calf systems (those having greater technological

adoption and management skills compared to traditional farmers in the region)

in this region has been recently estimated (21)

and the technological gap with the BASE system is 86% in beef productivity

(kg/ha/year) and 44% in weaning rate (table 5). This

difference is based on the application of technologies that increase forage

supply (greater area of cultivated pastures and annual forage crops) and improve

herd management techniques, such as greater supplementation of cows, higher stocking

rate, seasonal mating, and shorter age for first mating and weaning applied in

the top systems compared to the traditional systems.

Fernandez-Rosso et al. (2020) reported 63% more

beef production and 340% higher gross margin in systems that combined herd

management technologies such as early weaning (2 to 4 months) and implantation

of cultivated forage species, in the southwest of Buenos Aires province,

compared with traditional systems of that region.

Data available

from net aerial primary productivity (NAPP) and the quality of forage available

in the region under study are mainly reported for cultivated pastures (32, 36). The productive and economic simulations

carried out in this study were based on NAPP data of natural forage resources

using a combination of unpublished data of forage cuts validated by experts (table 2). However, alternative methodologies that allow for the

estimation of NAPP have been applied with promising results in other regions of

Argentina, such as the green index (22),

simulation models (4), and regression equations for forage cuts (17), and could be used in future studies.

In the northern

region of Santa Fe Province, there have been several public policies aimed at

assisting farmers in improving the productive efficiency of cow-calf systems

through subsidized loans and farm advisory support by applying and monitoring

health, nutritional, and reproductive management technologies (7, 29). However, the low adoption of technologies

and the current low productive and reproductive efficiency (table

5), which have remained stable for years (8, 9),

reflect the low effectiveness of those policies. This situation encourages a

deeper understanding of the causes of farmers’ scarce technological adoption.

In other important beef cattle breeding regions of the country, barriers to the

adoption of technologies in farming systems are mentioned. In cow-calf system

studies located in Buenos Aires province, it has stood out (17, 35) as adoption barriers of technology in the

cattle breeding systems of that region due to a lack of training in process

technologies, the absence of suitable public policies for the region, and the

producers’ partial dedication to the activity. Additionally, barriers related

to the lack of agricultural vocation among heirs and the absence of technical

assistance in low-tech systems have also been described (17).

The applied

participatory modelling methodology (17)

provided preliminary information and a “what if” analysis (25) of this important productive area. However,

the productive characterization of cow-calf traditional systems carried out in

this study will require additional research to refine farm information and to

define barriers to technological adoption in breeding systems in northern Santa

Fe. This understanding might aid in the better design of public policies, which

should include the social and cultural conditions of farmers (37). This methodology was also key to the

conservation and sustainable development of livestock systems in other

countries (44).

Conclusions

We combined the

available scarce data on traditional cow-calf systems in the northern region of

Santa Fe Province with the qualified knowledge provided by highly experienced

farm advisors, in order to establish a benchmark and to identify challenges for

future studies. Experts prioritized the improvement of forage supply and herd

management to increase the productivity of cow-calf systems. Implementation of

a rational grazing system for grasslands, training the farmer and farm staff on

herd management, and seasonal mating were the factors selected to be adopted in

the first place. The modelling study showed that increased SR, higher

supplementation and higher reproductive efficiency increased production and

economic results by 70 and 96%, respectively. The participatory modelling

methodology applied also allowed us to identify areas in which greater research

efforts are needed, such as more precise research information on farm

characterisation, forage production and quality, and farmers’ constraints for

technological adoption, which will be relevant inputs for designing and

promoting effective policies for the livestock sector.

Acknowledgements

The authors

express their gratitude to the Consorcio Regional de Experimentación

Agropecuaria Región Norte de Santa Fe (CREA) and its advisors for generously

providing the data and collaborating in discussions, offering valuable

suggestions for describing the traditional systems in the region. This research

is a part of the first author’s doctoral studies in Agriculture Science at the

Universidad Nacional del Litoral. This research was funded by a doctoral

scholarship from CONICET and a research project from Ministerio de Ciencia y

Tecnologia (PICT-2017-2271).

1. AACREA. 1990.

Normas para medir los resultados económicos en las empresas agropecuarias. Convenio

AACREA BANCO RIO. Buenos Aires. Argentina.

2. Abdala, A.

A.; Maciel, M. G.; Salado, E.; Aleman, R.; Scandolo, D. 2013. Pérdidas de

preñez en un rodeo de cría del norte de la provincia de Santa Fe. Rev. Arg.

Prod. Anim. 33(2):109- 115.

3. Andreu, M.;

Giancola, S. I.; Carranza, A.; Roberi, A.; Serena, J.; Carranza, F.; Nemoz, J.

P.; Meyer Paz, R. 2014. Resultados físicos y económicos de la implementación de

tecnologías críticas en sistemas ganaderos bovinos de ciclo completo en Cuenca

del Salado, provincia de Buenos Aires. Instituto Nacional de Tecnología

Agropecuaria, Centro de Investigación en Economía y Prospectiva (CIEP). Azul.

Argentina.

4. Berger, H.;

Machado, C. F.; Agnusdei, M.; Cullen, B. R. 2014. Use of a biophysical

simulation model (DairyMod) to represent tall fescue pasture growth in

Argentina. Grass and Forage Science. 69(3): 441-453. doi

10.1111/gfs.12064

5. Capozzolo, M.

C.; Crudeli, S. M.; Rollo, L. 2017a. Análisis de la base forrajera de un

sistema de cría bovina. Revista Voces y Ecos N° 37. Instituto Nacional de

Tecnología Agropecuaria, Estación Experimental Reconquista. Reconquista.

Argentina.

6. Capozzolo,

C.; Scarel, J.; Ocampo, M. E.; Ybran, R.; Hug, O.; Mitre, P. 2017b. Sistemas

ganaderos bovinos - Caracterización del distrito Toba. Instituto Nacional de

Tecnología Agropecuaria, EEA Reconquista. Reconquista. Argentina.

7. Cersan. 2006.

Proyecto Regional: Producción sustentable de carne bovina en la provincia de

Santa Fe. SANFE05. INTA - CERSAN.

8. Chimicz, J.

2006. Tipificación de la Cría bovina en Santa Fe. Una propuesta para la

elaboración de estrategias diferenciales de extensión. Instituto Nacional de

Tecnología Agropecuaria, Estación Experimental Rafaela, Rafaela. Argentina.

9. Chiossone, G.

2006. Sistemas de producción ganaderos del noreste argentino; Situación actual

y propuestas tecnológicas para mejorar su productividad. p. 120-137. En X

Seminario de manejo y utilización de pastos y forrajes en sistemas de

producción animal. 20-22 de abril. Maracaibo, Venezuela.

10. CNA. 2008.

Censo Nacional Agropecuario 2008.

https://www.indec.gob.ar/indec/web/Nivel4-Tema-3-8-87. (Date of consultation:

29/03/2023).

11. Dimundo, C.

D. 2021. Ciclo completo en ambientes marginales. En El NEA hacia la

intensificación ganadera. IPCVA. 24 de febrero. Reconquista, Argentina.

12. Di Rienzo,

J. A.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M. G.; Gonzalez, L.; Tablada, M.; Robledo, C.

W. 2011. InfoStat versión 2011. Grupo InfoStat. FCA. Universidad Nacional de

Córdoba. Argentina. http:// www.infostat.com.ar. (Date of consultation

29/03/2023).

13. Dolzani, M.;

Rosatti, G.; Yaya, A.; Gatti, E.; Bertoli, J.; Zoratti, O.; Ruiz, M.;

Podversich, F.; Bressan, E.; Tauber, C. 2019. Causas que limitan la adopción de

tecnologías en sistemas de producción de carne del norte de Santa Fe.

Argentina. VII Jornada de Difusión de la Investigación y Extensión. Esperanza.

Argentina.

14. FADA. 2021.

Aporte de las cadenas agroindustriales al PBI. Año 2020.

file:///C:/Users/Win10/Downloads/Producto%20Bruto%20Interno%202020.pdf (Date of

consultation 29/03/2023).

15. FAO-NZAGRC.

2017. Low-emissions development of the beef cattle sector in Argentina:

reducing enteric methane for food security and livelihoods. FAO. Rome.

16. Faverin, C.;

Bilotto, F.; Fernández Rosso, C.; Machado, C. F. 2019. Modelación productiva,

económica y de gases de efecto invernadero de sistemas típicos de cría bovina

de la Pampa Deprimida. Chilean Journal of Agricultural and Animal Sciences.

35(1): 14-25. doi: 10.4067/S0719-38902019005000102.

17. Fernández

Rosso, C.; Bilotto, F.; Lauric, A.; De Leo, G. A.; Torres Carbonell, C.;

Arroqui, M. A.; Sorensen, C. G.; Machado, C. F. 2020. An innovation path in

Argentinean cow–calf operations: Insights from participatory farm system

modelling. Systems Research and Behavioral Science. 1-15. doi:10.1002/sres.2679

18. Fuglie, K.

O. 2012. Productivity growth and technology capital in the global agricultural

economy. In: Fuglie, K. O., Wang, S. L., Ball, V. E. (Eds.). Productivity

Growth in Agriculture: An International Perspective. CAB International,

Cambridge. p. 335-368.

19. Giorgi, R.;

Tosolini, R.; Sapino, V.; Villar, J.; León, C.; Chiavassa, A. 2007.

Zonificación agroeconómica de la Provincia de Santa Fe. Delimitación y

descripción de las zonas y subzonas agroeconómicas. Publicación Miscelánea N°

110. Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria. Estación Experimental

Rafaela. Argentina.

20. Greenwood,

P. 2021. Review: An overview of beef production from pasture and feedlot

globally, as demand for beef and the need for sustainable practices increase.

Animal: an international journal of animal bioscience. 15(2): 100295. doi 10.1016/j.animal.2021.100295

21. Gregoretti,

G.; Baudracco, J.; Dimundo, C.; Alesso, A.; Lazzarini, B. y Machado, C. 2020.

Caracterización productiva de sistemas de cría tecnificados de la región centro

norte de Argentina. Chilean Journal of Agricultural and Animal Sciences. 36(3):

233-243. doi 10.29393/chjaas36-22cpgg60022.

22. Grigera, G.;

Oesterheld, M.; Pacín, F. 2007. Monitoring forage production for farmers’

decision making. Agricultural Systems. 94: 637-648. doi

10.1016/j.agsy.2007.01.001

23. INTA. 2018.

Estación Meteorológica Reconquista. Instituto Nacional de Tecnología

Agropecuaria. https://inta.gob.ar/documentos/estacion-meteorologicareconquista

(Date of consultation 29/03/2023).

24. INTA. 2020.

Estación Meteorológica Reconquista. Instituto Nacional de Tecnología

Agropecuaria. https://inta.gob.ar/documentos/estacion-meteorologica-reconquista

(Date of consultation 29/03/2023).

25. Machado, C.

F.; Berger, H. 2012. Uso de modelos de simulación para asistir decisiones. en sistemas de producción de carne. Revista Argentina de

Producción Animal. 32: 87-105.

26. MAGyP. 2023.

Informes Técnicos y Estimaciones. Ministerio de Agricultura Ganadería y Pesca

de Argentina. https://www.argentina.gob.ar/agricultura (Date of consultation

29/03/2029).

27. Marino, G.;

Pensiero, J. F. 2003. Heterogeneidad florística y estructural de los bosques de

Schinopsis balansae (Anacardiaceae) en el sur del Chaco Húmedo.

Darwiniana 41:17-28. Doi 10.14522/darwiniana.2014.411-4.203

28. Martín, S.;

Pensiero, J. F.; D´Angelo, C. D. 2006. Bosques para siempre. Las prácticas para

un manejo sustentable de los bosques santafesinos. Mesa Agroforestal

Santafesina. Argentina.

29. MPSF. 2019.

Ministerio de la Producción de Santa Fe. 2019. Programa Más Terneros. Santa Fe.

https://www. santafe.gob.ar/index.php/tramites/modul1/index?m=descripcion&imprimir=1&id=245848.

(Date of consultation 29/03/2023).

30. OECD-FAO.

2023. Perspectivas agrícolas 2020-2029. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/

sites/498ef94ees/index.html?itemId=/content/component/498ef94e-es#sectiond1e21140.

(Date of consultation 29/03/2003).

31. Oenema, O.;

De Klein, C. A. M.; Alfaro, A. 2014. Intensification of grassland and forage

use: Driving forces and constrains. Crop and Pasture Science. 65(6): 524. doi 10.1071/CP14001

32. Oprandi, G.;

Coloombo, F.; Parodi, M.I. 2014. Grama rhodes, una alternativa productiva para

los sistemas ganaderos del norte de Santa Fe. Revista Voces y Ecos. 31: 26-27.

33. Pacín, F.;

Oesterheld, M. 2015. Closing the technological gap of animal and crop

production through technical assistance. Agricultural Systems. 137: 101-107. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2015.04.007

34. Pensiero, J.

F. 2017. Guía de reconocimiento de herbáceas del Chaco Húmedo. Características

para su manejo. Buenas Prácticas para una ganadería sustentable. Fundación Vida

Silvestre y Aves Argentinas.

35. Recavarren,

P.; Bruno, S.; Torres Carbonell C.; Balda, S.; Kaspar, G. 2021. Resultados del

taller “Sistemas de cría vacuna: tecnologías, innovación y extensión en el

CeRBAS”. Ediciones INTA; Estación Experimental Agropecuaria Balcarce. 16 p.

36. Saucedo M.

E.; Castro, C. G.; Obregón, H. J.; Dolzani, E. 2016. Introducción de nuevas

pasturas en el norte de Santa Fe. Revista Voces y Ecos. 35: 47-49.

37. Serra, R.;

Kiker, G. A.; Minten, B.; Valerio, V. C.; Varijakshapanicker, P.; Wane, A.

2020. Filling knowledge gaps to strengthen livestock policies in low-income

countries. Global Food Security. 26: 100428. Doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100428.

38. Tilman, D.;

Cassman, K.; Matson, P.; Naylor, R.; Polasky, S. 2002. Agricultural

sustainability and intensive production practices. Nature. 418: 671-677.

39. Troncoso

Sepúlveda, R. A.; Cabas Monje, J. H.; Guesmi, B. 2023. Land tenure and cost

inefficiency: the case of rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivation in Chile.

Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo.

Mendoza. Argentina. 55(2): 61-75. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.109

40. Uniagro.

2019. Software Baqueano cría vacuna. www.uniagro.com.ar

41. USDA. 2019a.

Livestock and Product Semi-annual.

https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/report/downloadreportbyfilename?filename=Livestock%20and%20Products%20Semiannual_Canberra_Australia_3-1-2019.pdf

(Date of consultation 29/03/2023).

42. USDA. 2019b.

Cattle and Beef Semi-Annual Report 2019.

https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/report/downloadreportbyfilename?filename=Cattle%20and%20Beef%20Semi-Annual%20Report%202019%20for%20New%20Zealand_Wellington_New%20Zealand_3-12-2019.pdf

(Date of consultation 29/03/2023).

43. USDA. 2023.

Livestock and Poultry: World Markets and Trade.

https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/circulars/livestock_poultry.pdf (Date of

consultation 29/03/2023)

44.

Vargas-López, S.; Bustamante-González, A.; Ramírez-Bribiesca, J. E.;

Torres-Hernández, G.; Larbi, A.; Maldonado-Jáquez, López-Tecpoyotl, Z. G. 2022.

Rescue and participatory conservation of Creole goats in the agro-silvopastoral

systems of the Mountains of Guerrero, Mexico. Revista de la Facultad de

Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 54(1):

153-162. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.074