Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 55(2). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2023.

Original article

Land

tenure and cost inefficiency: the case of rice (Oryza sativa L.)

cultivation in Chile

Tenencia

de tierra y costo ineficiencia: el caso del cultivo de arroz (Oryza sativa L.)

en Chile

Ricardo Andrés

Troncoso Sepúlveda1*,

Juan Hernán Cabas

Monje2,

Bouali Guesmi3

1Universidad

Católica del Norte. Departamento de Administración. Avenida Angamos. 0610. C.

P. 1249004. Antofagasta. Chile.

2Universidad

del Bío-Bío. Departamento de Gestión Empresarial. Grupo de Investigación en

Agronegocios. Avda. Andrés Bello 720. Casilla 447. C. P. 3800708. Chillán.

Chile.

3Centro

de Economía y Desarrollo Agroalimentario (CREDA-UPC-IRTA). Campus del Baix

Llobregat-UPC. Esteve Terradas. 8. Castelldefels. 08860. Barcelona. España.

*ricardo.troncoso@ucn.cl

Abstract

This study aims

to examine the impact of land tenure arrangements on production costs in a

sample of rice farmers in Ñuble Region, Chile. A stochastic frontier model was estimated

using the primal approach on a panel of 107 farmers in 2014-2015. Production cost

was broken down into frontier costs and inefficiency. According to findings,

economic inefficiency raises rice production costs by 82%. Technical

inefficiency accounts for a 61% increase, while allocative inefficiency

accounts for 21%. Across tenure types, land is the input with the highest

misallocation, accounting for 93% of allocative inefficiency costs. Sharecropping

is the arrangement allocating inputs most efficiently, producing significant differences

in production costs relative to leasing and ownership. This finding suggests

that before designing a policy to induce a tenure system, it is necessary to

evaluate specific cases as there is no system superior to another, strictly

speaking.

Keywords: rice production,

land tenure, stochastic model, cost inefficiency, misallocation

Resumen

El propósito de

este trabajo es analizar el impacto del acuerdo de tenencia de tierra sobre los

costos de producción, en una muestra de productores de arroz en la Región de

Ñuble, Chile. Usando un panel de 107 agricultores para los años 2014 y 2015, se

estimó un modelo de frontera estocástica, mediante el enfoque primal, y

descompuso el costo de producción en costos de frontera e ineficiencia. Los

resultados muestran que la ineficiencia económica incrementa en 82% los costos

de producción de arroz. Un 61% del incremento se debe a ineficiencia técnica y

21% a ineficiencia en asignación. Transversal al tipo de tenencia, tierra es el

factor de producción que presenta la peor asignación, contribuyendo en un 93% a

los costos por este tipo de ineficiencia. Mediería, es el acuerdo que asigna

los factores con mayor eficiencia, produciendo diferencias significativas en

los costos de producción en relación con arriendo y propiedad. Este hallazgo,

sugiere que antes de diseñar una política para inducir un sistema de tenencia,

es necesario evaluar casos específicos, ya que no existe un sistema que en

estricto rigor sea superior a otro.

Palabras clave: producción de

arroz, tenencia de la tierra, modelo estocástico, ineficiencia de costos, mala

asignación

Originales: Recepción: 19/04/2023 - Aceptación: 22/09/2023

Introduction

Rice is a staple

food for half of the world’s population and the third most-produced cereal

after maize and wheat on a world basis. More than 90% of total production is

concentrated in Asian regions, primarily in China, India, and Indonesia, where

local production accounts for 66% of global output (14,

45). In Chile, production is concentrated in Maule and Ñuble regions,

with an average of 83,368 tons of rice available for human consumption from

2012 to 2022. Historically, this volume has been insufficient to meet 40% - 45%

of the domestic demand, with the remainder imported primarily from Argentina,

Uruguay, and Paraguay (36). National

output has dropped by 30.4% over the last decade, due not only to adverse

climatic factors such as frost and water scarcity, but also to current high

input prices for fertilizers and pesticides, high land prices, labor shortages,

and low market prices, which have significantly reduced output (35). These factors put farmers under pressure to

become more efficient in rice production and input utilization to avoid

additional costs and make farms profitable. This raises several questions. One

of them refers to the study of the characteristics, unique to the farmer, the

farm, and the environment, which help understand why one farmer is more

cost-efficient than another and, particularly, what role tenure arrangements to

exploit the land play. The latter is the focus of this study.

Tenure

arrangements, which govern land exploitation, can have an impact on production

and cost efficiency. Landlord, fixed rent, and sharecropping are the most

common land tenure systems documented in the literature (1). A large body of literature discusses the

factors influencing agricultural production efficiency. However, studies on the

impact of various types of land tenure arrangements on production costs are

scarce. Works such as Ackerberg and Botticini (2000),

Alem et al. (2018) and Islam

(2018), conclude that land tenure, either leased or owned, favors technical

efficiency levels, but they do not break down production costs into technical

inefficiency and input misallocation inefficiency cost. Other papers, decompose

and analyze the determinants of technical and allocative efficiencies, but they

do not estimate the costs of these inefficiencies, nor analyze differences

between land tenure arrangements or the degree of input misallocation and its

impact on costs (13, 19, 26, 37, 44).

This paper aims

to analyze differences in production costs, particularly those due to technical

and allocative inefficiencies between ownership, leasing, and mediation arrangements

among rice producers in Chile. No other studies deal with this relationship on

a cost basis, nor estimate input allocation problems among small rice farmers

in Chile. For this purpose, a stochastic frontier model was implemented. Using

the primal approach, the degree of input misallocation was estimated and the

cost of production was broken down into frontier costs and technical and

allocative inefficiencies on a farm basis. The model is applied to a panel data

of rice farmers in the Ñuble Region, Chile, collected during the years 2014 and

2015.

This paper is

structured as follows: The second part concisely describes rice cultivation and

its production chain in Chile. The third section briefly describes the

agricultural land tenure system in the country and analyzes its evolution over

time. The fourth section introduces the theoretical model and explains the

methodology used for this study. The fifth section discusses the data used in

the research. In the sixth section, the results obtained are presented and

analyzed. Finally, in the seventh section, the main conclusions derived from

this study are summarized.

Rice cultivation and value chain in

Chile

Rice cultivation

in Chile dates back to 1925, although it only acquired comercial relevance a

few decades later. The introduction of this crop made it possible to take

advantage of an extensive area of soils previously considered marginal, as they

lacked viable alternatives for agriculture. This allowed a more intensive use

of these soils and offered a more favorable economic option (17, 33). Currently, the national area dedicated

to rice cultivation is concentrated in the central-south zone of Chile, with

Maule and Ñuble being the most relevant regions. In the last decade, the

cultivated area has oscillated around 24,000 hectares, with a peak of 29,500

hectares in the 2017/18 season and a mínimum of 20,700 hectares recorded in the

2021/22 season. This has resulted in an average of 83,368 tons of rice

available for human consumption and yields of 53% for milled rice or rice

available for human consumption.

The internal

value chain comprises producers, processors, importers/distributors, and

retailers. Producers or farmers are concentrated mainly in the Maule and Ñuble

Regions. According to the 2007 Agricultural Census, there are about 1,500 farms

dedicated to rice cultivation, with slightly fewer farmers involved in this

activity. Notably, most of these farms, specifically more than 70%, have

cultivation areas that do not exceed 50 hectares. This reflects that rice

production in Chile mainly comprises small and medium-scale farmers.

On the other

hand, only a small percentage, approximately 1.6%, has a farm size that exceeds

500 hectares (33). The national

processing industry comprises companies that acquire raw materials through

long-term contracts or spot purchases directly from farmers. These companies

usually have reception, storage, and processing plants located in the communes

of the Maule and Ñuble regions, where rice production in the country is concentrated.

Some of these companies also play an essential role as importers and wholesale

distributors in the Chilean rice market. The rice importing and distributing

sector in Chile comprises companies that play a crucial role in the supply

chain of this product in the country. These companies import rice from

countries such as Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay to meet domestic demand (36). In addition to importing, these companies

handle the wholesale distribution of processed rice ready for consumption in the

Chilean market. The retail sector in the rice supply chain in Chile is composed

of companies engaged in the retail marketing of rice products directly to

consumers. Approximately 70% of rice sales in Chile are estimated to be

concentrated in these retail companies, including supermarket chains,

hypermarkets, and convenience stores (33).

It investigates

the differences in production costs, particularly those due to technical and

allocative inefficiencies between ownership, leasing, and mediation regimes among

rice producers in Chile. In the next section, a brief description of Chile’s

agricultural land tenure system will be provided, and its evolution over time

will be analyzed. This will serve as a context for understanding how different

ownership regimes can influence production costs and efficiency in rice

cultivation in the country.

Agricultural

land tenure in Chile

Before the

1967-1973 agrarian reform, the predominant tenure structure in Chile was the

latifundio-minifundio system, constituted by relations of dependence between

landowners and peasants and characterized by a strong hierarchy and coercion,

like the European manorial system, but lacking legal ties over land ownership (16). The tenancy relationship was the main link

between an employer and his workers. It consisted of a contract through which

the employer ensured stable labor in exchange for meeting the basic needs of

his tenants. This contract passed from generation to generation, along with the

inheritance of the land from the master to his relatives. The precarious

working conditions at the time caused a massive exodus of workers to cities in

search of better opportunities. This, together with the unequal distribution of

land, which limited the productive expansion of the sector, and the social

pressure and economic crisis at the time triggered the agrarian reform, aiming

to improve land distribution and put an end to the latifundio-minifundio

system. Thus, in 1962, the first agricultural reform law was passed, which made

it possible to redistribute state lands among peasants and organize fiscal

institutions to reform the countryside (16).

This process was further intensified during the Popular Unity (Spanish: Unidad

Popular, UP)1 government from 1970 to 1973. It represented the

massive redistribution of 9 million hectares of land to peasants, on legal and

institutionally backed conditions (46).

However, in 1973, the military government initiated the gradual restitution of

a portion of the confiscated lands and the sale of some of the properties with

legal problems through the so-called agrarian counter-reform. This process was

not free of political, civil, and economic tensions.

1The Unidad

Popular was a left-leaning political coalition in Chile that supported the

successful candidacy of Salvador Allende in the 1970 presidential elections.

Currently,

several agricultural land tenure systems coexist in Chile, varying in contract

formality. According to the latest Agricultural Census, the most common forms

of land tenure in Chile are:

- Ownership

with a registered title: Land over which the producer has possession and is

covered by a title registered in the Real Estate Registry.

- Ownership

without title (irregular): Land the farmer exploits as owner without a

registered title deed. It includes those coming from de facto divided

inheritances, irregular sales without being adequately registered, those

obtained de facto by exchange with irregular title, those assigned by public

entities without regularizing their title, etc.

- Royalty: Land the farmer

uses as payment for services rendered as manager, laborer, or other employment

relationship.

- Leased: Land available

to the farmer for use in his operation under a lease contract. As agreed with

the landowner, he pays an annual rent for the land in cash, agricultural

products, or a combination of both.

- Sharecropping:

Land

used by the producer - independent mediator - in which the owner is remunerated

with part of the production obtained, either in kind or its equivalent in

money, following the conditions established by the parties.

- Ceded: Land used by the

producer, which was voluntarily given to him by some person and for the use of

which he makes no payment.

- Occupied: Public or

private land used by a producer without the consent of the legitimate possessor

and payment.

As agreed with the landowner, he pays an annual rent for the

land in cash, agricultural products, or a combination of both; sharecropping,

land received as a royalty, ceded land, and occupied land, the latter

corresponding to public or private land used without owners’ consent. According

to the share of owned, leased, and sharecropped land in the national total,

65.4% of agricultural land is owned, 8.5% is leased, and only 1.5% is

sharecropped. Despite the low national share of the latter, both arrangements

are relevant in some regions. For example, 24.3% of the leased properties and

43.5% of the properties under mediation are located in Maule, Ñuble, and Bíobío

regions (20). This is due to different

reasons: first, Maule and Ñuble Regions are two of the country’s main

agricultural production areas, strongly influencing the number of leasing and

sharecropping contracts (21) and second,

landholdings in these regions, mainly Ñuble, the region of interest, are

smaller relative to the national average (34).

Due to the

inherent nature of farming, access to finance is often linked to the use of

land as collateral. In this context, farmers operating smaller farms often face

limitations in accessing financial resources. This suggests the need to

consider more efficient alternatives, such as tenure systems based on leases

and sharecropping, specially designed for small farmers, to compensate for the

scarcity of resources (40, 41). The

latter makes up the focus of this study, i.e., analyzing the differences

in farm efficiency levels, according to the type of tenure arrangement.

Model

This study uses

the primal system approach proposed by Schmidt et al.

(1979) and extended by Kumbhakar et al. (2006)

to identify and measure technical and allocative inefficiencies for a sample of

Chilean producers. This approach consists of a production function and

first-order conditions of the cost minimization problem. It is algebraically

equivalent to the cost system of the self-dual production function (27), but it starts from a parametric production

function rather than a cost function.

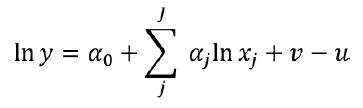

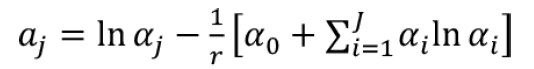

Consider a

Cobb-Douglas production frontier with j inputs, as proposed by Battese et al. (1988).

where:

y = denotes output

xj = jth input

aj = are technology

parameters to be estimated

v = a random error

term capturing events beyo nd farmers’ control, which is independently and

identically distributed.

u= a non-negative

term capturing persistent technical production inefficiency, independently and

identically distributed as ![]() .

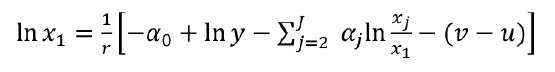

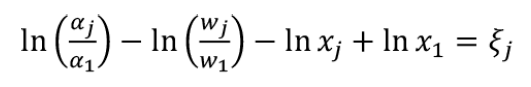

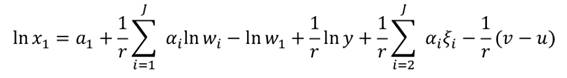

Expressing equation (1) in terms of In x1

we obtain,

.

Expressing equation (1) in terms of In x1

we obtain,

where:

![]() are the returns to

scale. Equation (2) can be seen as a

function of input distance. Following to Kumbhakar et

al. (2020); Musau et al. (2021) and Schmidt and Lovell (1979), the first order conditions of

the cost minimization problem are2:

are the returns to

scale. Equation (2) can be seen as a

function of input distance. Following to Kumbhakar et

al. (2020); Musau et al. (2021) and Schmidt and Lovell (1979), the first order conditions of

the cost minimization problem are2:

2Input ratios can

be treated as exogenous since they are a function of prices (exogenously

given).

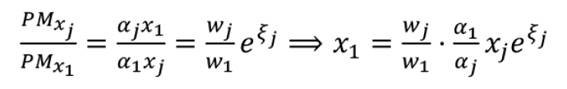

where:

PM xj = the marginal

product of xj and wj is the price of input j. The term ![]() represents the inefficient allocation of input

j relative to input 1, the numeraire. Given linear Price homogeneity, it

is only possible to estimate negative inefficiency. So, input must be numeraire

to identify (6). Then, if

represents the inefficient allocation of input

j relative to input 1, the numeraire. Given linear Price homogeneity, it

is only possible to estimate negative inefficiency. So, input must be numeraire

to identify (6). Then, if ![]() there will be an underutilization of input j

relative to input 1, while if

there will be an underutilization of input j

relative to input 1, while if ![]() will be overused relative to input 1. Using

logarithms for the first-order condition (3),

will be overused relative to input 1. Using

logarithms for the first-order condition (3),

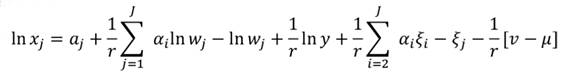

Then, using the

distance function (2), equations (3, 4) derived from the first-order conditions,

and solving for xj, the following input demand functions can be obtained

logarithmically,

where:

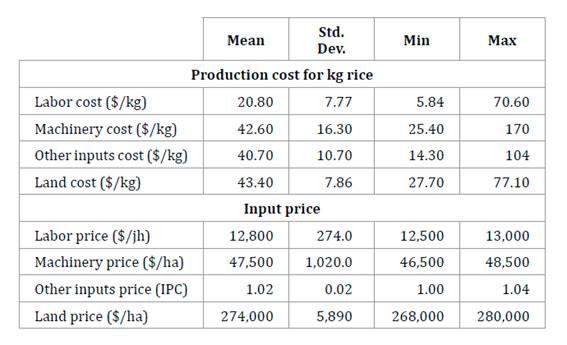

The production

cost function can be obtained from the input demands, taking the following form

where:

As pointed out

by Kumbhakar et al. (2006), Musau et al. (2021) and Vasconcelos

(2020), the impact of technical and allocative inefficiency on production

costs can be obtained by comparing the cost function with and without

inefficiencies. In the cost function, technical inefficiency increases costs by

![]() , while allocative inefficiency increases them

by 100(E - Inr)%. When there is no

inefficient input allocation, i.e., when

, while allocative inefficiency increases them

by 100(E - Inr)%. When there is no

inefficient input allocation, i.e., when ![]() ,

the E and In r terms are equal. Moreover, there is an inverse

relationship between the firm’s returns to scale (r) and both

inefficiencies. More productive firms should also be more efficient in

production and input allocation.

,

the E and In r terms are equal. Moreover, there is an inverse

relationship between the firm’s returns to scale (r) and both

inefficiencies. More productive firms should also be more efficient in

production and input allocation.

Data

This study uses

a balanced panel of 107 rice producers from Ñiquén and San Carlos communes in

Ñuble Region, Chile. Data were collected by the Agricultural and Livestock

Research Institute (INIA for its acronym in Spanish), particularly, the

Technical Assistance Program (SAT, for its acronym in Spanish) from 2014 to

2015. They provide information on yield (kg), output value (CL$), land use

(ha), production costs (CL$), public and private infrastructure, and farmer

characteristics. Following the methodology described by Alem

et al. (2018) and Henderson (2015), the

prices of the inputs used in this study were collected from secondary sources.

Prices per man-day (MD) reflect wages for hired labor, the machinery cost is

measured in CLP per hectare, and the price of land (ha) corresponds to the

equivalent lease’s market value, representing the opportunity cost. These price

data were obtained from the Chilean Ministry of Agriculture’s Office of

Agricultural Studies and Policies (ODEPA, for its acronym in Spanish),

guaranteeing their reliability and relevance to the country’s agricultural

context. For other inputs (seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides), the Consumer

Price Index (CPI) was used, as suggested by Musau et

al. (2021). Prices are expressed in Chilean pesos (CL$) for 2014.

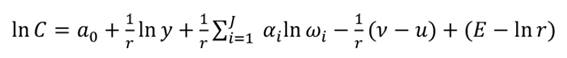

Table

1, shows summarized statistics of the production cost structure and factor

prices per kg of output. Labor costs are the lowest and fluctuate between $5.84

and $70.60, with an average of $20.80.

Table

1. Descriptive statistics of production

costs and input prices.

Tabla 1. Estadísticas

descriptivas de costos de producción y precios de insumos.

Machinery, other

inputs, and land average about $40 and $43 per kg of rice, dominating 86% of

the overall cost structure. As expected, the price per hectare of land is the

highest, followed by the price per hectare of agricultural machinery and the

price per man-day. For estimating the stochastic production frontier, one

output and four input variables were used. Total output was measured in

kilograms of rice, land in hectares, labor in MD, machinery in hectares, and

the other inputs (seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides) in thousands of Chilean

pesos as of 2014.

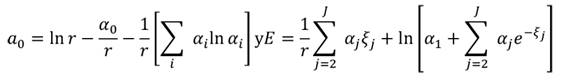

Table

2 shows the summarized statistics of the variables used in the production

function. In terms of output, the maximum production level reached 141 tons in

2015, representing a 68% drop, compared to the maximum in 2014.

Table

2. Descriptive statistics of output and

inputs.

Tabla 2. Estadísticos

descriptivos de productos e insumos.

On average,

there was also a significant drop, albeit less pronounced, in the production

level, falling back by 9.1%, compared to the previous figure. This result is in

line with the decrease in the total area cultivated with rice in Ñuble Region,

which fell by 18% in 2015, compared to 2014 (32).

Land use and agricultural machinery also show significant drops of 9.1% and

37.5% on average between periods, respectively. The decrease in machinery use

may reflect a capital investment drop, which is in line with the decline in the

rice area. In contrast, the number of man-days and the cost of other inputs,

considering expenditure on seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides, increased by

about 3% in 2015.

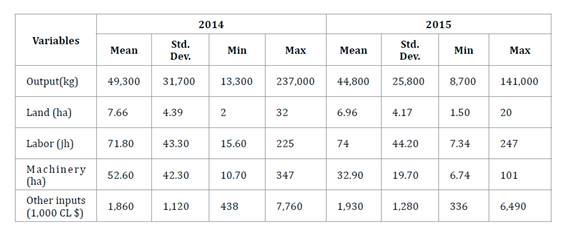

Regarding

technical and allocative inefficiency cost determinants, annual averages were

calculated for each determinant as a model was estimated by assuming persistent

technical inefficiency. This arrangement makes sense because the panel is small

and few observations demonstrate variation between the relevant years. The

estimations were adjusted to account for these observations (41). Table 3, shows descriptive

statistics for variables related to farmers’ characteristics, public

agricultural infrastructure, and land tenure systems.

Table

3. Descriptive statistics determining

allocative and technical inefficiency costs.

Tabla 3. Estadísticas

descriptivas determinantes de los costos de ineficiencia técnica y de

asignación.

Educational

level was represented by a categorical variable, as follows: No education (0),

incomplete primary education (1), complete primary education (2), incomplete

secondary education (3), complete secondary education (4), incomplete tertiary

education (5), and complete tertiary education (6). Only one farmer claimed to

have completed college education, whereas more than 75% of the farmers said they

had only completed their primary education. The difference between the

administration date of the survey and the start of business operations in the

rice industry served as the unit of measurement for farmer experience, which

was expressed in years. Farmers said they had been producing rice for an

average of 12 years; the farmer with the least experience said they had been

doing it for two years, while the farmer with the most said they had been doing

it for 35 years. The percentage of total agricultural land set aside for rice

farming reflects specialization. Farmers in the study devote an average of

50.8% of the land to this crop. Concerning access to water, a dummy variable

was created, assuming a value of 1 when the farm is supplied from a rainwater

reservoir and 0 otherwise. On average, 43% reported access to water from a

pool. Finally, on land tenure systems, 44% of the farmers report working the

land by sharecropping and just under 20% report renting the land.

Results

and discussion

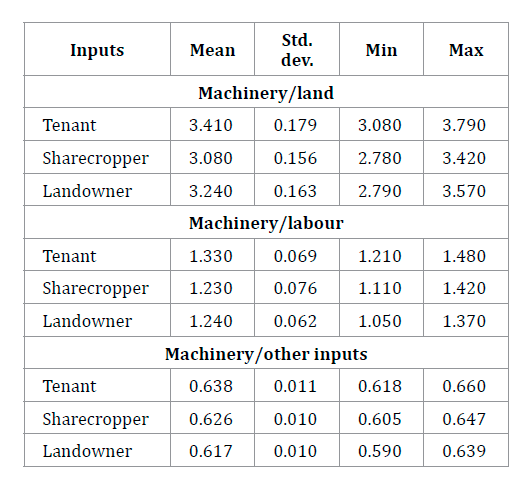

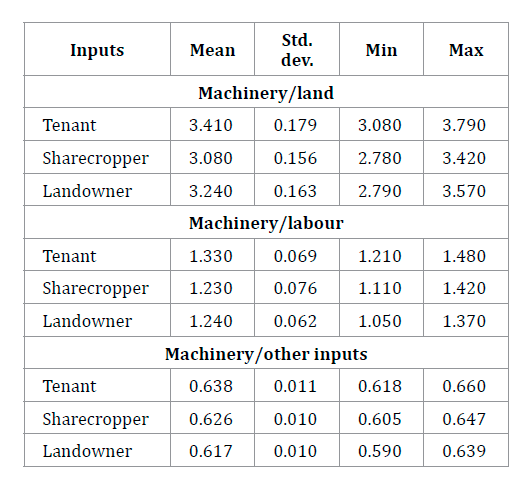

Table

4 shows inefficient allocation parameters ![]() for land, labor, and other inputs relative to

machinery by land tenure type.

for land, labor, and other inputs relative to

machinery by land tenure type.

Table 4. Estimates

of inefficient allocation by inputs and tenure.

Tabla 4. Estimaciones

de asignación ineficiente por insumos y tenencia.

Results suggest

that, on average, none of the inputs is used optimally and there is inefficient

allocation. On an input basis, land shows the highest inefficiency level, with

an ![]() three times higher than optimal across all

tenure types, revealing a high degree of under-utilization, relative to

three times higher than optimal across all

tenure types, revealing a high degree of under-utilization, relative to ![]() ,

thus indicating efficient input allocation. In labor, this situation is also

observed, but to a lesser extent, fluctuating between 23% and 33%. On the other

hand, other inputs are the only over-utilized factor, with a parameter between

0.617 and 0.638. This result may be associated with the high fertilizer and

soil preparation costs incurred by farmers to mitigate the impact on

productivity due to weed proliferation. Assessments in the Ñuble Region

determined average yield losses of up to 30% due to poor weed control (38).

,

thus indicating efficient input allocation. In labor, this situation is also

observed, but to a lesser extent, fluctuating between 23% and 33%. On the other

hand, other inputs are the only over-utilized factor, with a parameter between

0.617 and 0.638. This result may be associated with the high fertilizer and

soil preparation costs incurred by farmers to mitigate the impact on

productivity due to weed proliferation. Assessments in the Ñuble Region

determined average yield losses of up to 30% due to poor weed control (38).

Concerning land

tenure, on average, landlords are the most inefficient input allocators, while

sharecroppers are the least inefficient. This finding is generally not supported

by empirical literature. Bolhuis et al. (2021),

Chen (2017) and Chen et

al. (2022), found that greater access to land rental markets via land

titling programs would significantly contribute to reducing the inefficient

allocation of productive factors. However, some theoretical and empirical

contributions provide insights that may aid in explaining this result. Authors

such as At et al. (2019), Jacoby et al. (2009), Jamal

et al. (2009), Pi (2013), argue that

sharecropping efficiency, compared to other land tenure arrangements, can be

conditioned by the landowner’s monitoring efforts, benefits division, and

landholders’ external choices. In other words, sharecropping can be expected to

be more efficient because the interests of both sides in sharing benefits make

monitoring closer and more effective. These two characteristics are not

observed in the sample, but there is educational information from the farmers

that could be associated with access to external options for income generation.

In our sample, sharecroppers have, on average, a lower schooling level

(incomplete secondary) than tenant farmers (complete secondary). This

characteristic may be a sign of greater dependence on rice cultivation for

income generation, fewer external options, and, thus, greater commitment to

devote more time and effort to rice production. This effect does not

necessarily hold for other tenure modalities. For example, in cases of lease or

land ownership, when the farmer needs to hire workers at a fixed rent,

regardless of performance, there may be less incentive for productivity as wage

needs to be indexed to performance. This is not the case in a sharecropping

arrangement as each party’s income is a fraction of the total benefits, a function

of their effort.

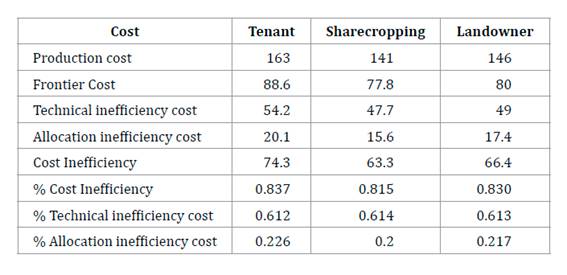

From equation (7), it is evident that inefficient input

allocation will negatively impact production costs. This impact was estimated

using these results and technical inefficiency estimates from the input

distance function (2). Table

5, shows the average cost to produce 1 kg of rice under different

inefficiency constraints.

Table

5. Average production cost per kg under

different inefficiencies (CLP$).

Tabla 5. Costo

promedio de producción por kg bajo diferentes ineficiencias (CLP$).

As expected,

sharecropping farms show the lowest production costs on average, i.e.,

13.5% lower than leased farms and 3.4% lower than owned farms. Using

totelling’s Generalised T-squared tests of means, both the cost of technical

inefficiency and allocative inefficiency were found to be significantly

different than zero at 1%. Ignoring these costs could lead to underestimating

actual farm production costs, regardless of tenure arrangement. Results

indicate that economic inefficiency costs exceed frontier costs by 82% in the

three tenure arrangements. This percentage is higher, compared to estimates

reported for grain production in Norway (3)

and China (46), and lower than estimates

for Indonesia (4). On average, 74% of economic

inefficiency is attributable to technical inefficiency (61% absolute) and the

remaining 26% to allocative inefficiency (21% absolute), i.e., most cost

inefficiency is associated with long-term rigidities that are external but

affect farm management (9, 29). Both

inefficiencies turn into a production cost increase per kg of rice. In line

with results in table 4, sharecropping shows the lowest monetary cost

inefficiency ($77.8), followed by landowners ($80) and tenants ($88.6). These

differences can be partly explained by the fact that sharecroppers have

frontier costs that, on average, are 7.5% lower than the other tenure

arrangements, but mainly because they have lower inefficient allocation costs

due to input misallocation (table 4). The latter may be

related to monitoring efforts, benefit sharing, and sharecroppers’ eventual

lower access to external income sources.

This perspective

raises an interesting explanation for the potential benefits of sharecropping

as a more efficient production organization system compared to land ownership

and leasing systems, especially from a wage point of view. One of the critical

aspects is that sharecropping is based on a performance-linked incentive

system, in contrast to the time-based compensation that is more common in land

ownership and leasing systems. In sharecropping, workers have a greater

incentive to deploy additional effort and perform all necessary tasks more

efficiently, which can reduce or even eliminate the need for supervisory costs

typical in wage labor systems. In addition, sharecropping can be a viable

alternative when there are labor shortages or financial difficulties in paying

wages. This is because sharecropping arrangements often involve a more

equitable sharing of risks and rewards between the landowner and the farmer,

which can benefit the farmer and the farm from an economic perspective. From a

temporal perspective, it is also important to consider that in agricultural

production, there are stages or cycles in which the marginal productivity of

labor may be lower than the wage paid, which would not be economically optimal.

Sharecropping can mitigate this problem by encouraging greater labor intensity

relative to other contracting systems, which could improve farm economic

performance (8).

In summary,

sharecropping may offer economic and efficiency advantages in the organization

of agricultural production, especially in comparison to land ownership and

leasing systems, due to its performance-based incentives and its ability to

adapt to variable situations in agriculture.

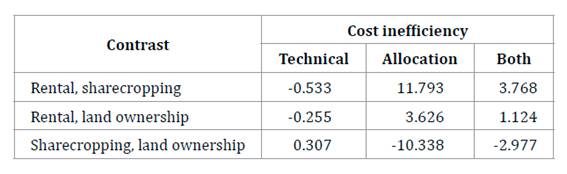

Table

6 shows the results of Welch’s mean difference test for inefficiencies,

according to tenure agreement.

Table

6. Mean difference test.

Tabla 6. Prueba

de diferencia de medias.

The first column

indicates no statistically significant differences in technical cost

inefficiency among lease, sharecropping, and ownership. However, there are

significant differences between 1% at allocative inefficiency and total

inefficiency (columns 2-3). These results suggest that time-invariant

structural and institutional factors affect farm management across farm tenure

types. Those differences in efficiency may be related to farmers’ ability to

allocate inputs efficiently. At least in this sample, this ability would be

related to tenure type.

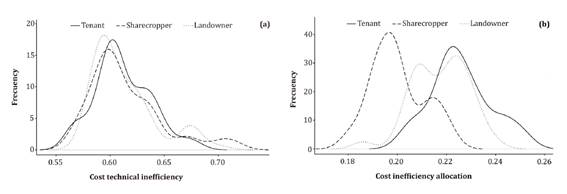

Figure

1 shows the kernel density distributions of both types of inefficiency.

(a) shows the kernel distribution of technical

inefficiency costs; (b) shows allocation inefficiency costs.

(a) muestra la distribución

kernel de los costos de ineficiencia técnica; (b) muestra los costos de

ineficiencia en la asignación.

Figure 1. Cost

inefficiency distribution, according to property tenure.

Figura 1. Distribución

de la ineficiencia de costos, según tenencia de la propiedad.

In the left-hand

panel, the resulting distributions reveal that technical inefficiency scores

are skewed to the right for each tenure arrangement. This is confirmed by the

0.403,1.235, and 1.196 skewness coefficients for leasehold, sharecropping, and

ownership, respectively. The three distributions look similar, having a high

score density, with 92% of the farms located between 0.55 and 0.65. In the

right-hand panel, allocation inefficiency distributions for leasing and

sharecropping are asymmetric to the right, with coefficients of 0.304 and

0.373. At the same time, owners show an asymmetric distribution to the left

with a -0.382 coefficient. Sharecropping shows a high density towards lower

inefficiency scores than the other distributions. Particularly, 87% of the

farms are between 0.18 and 0.21.

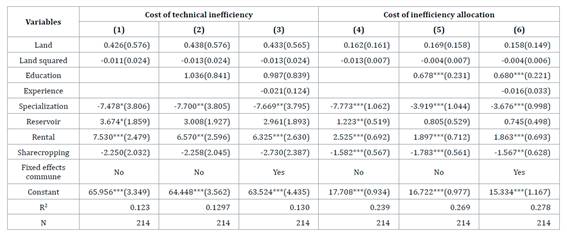

Empirical

results for the monetary cost determinants of technical and allocative

inefficiency are shown in table 7.

Table

7. Cost determinants of technical and

allocative inefficiency.

Tabla 7. Costos

determinantes de la ineficiencia técnica y de asignación.

Standard errors in parenthesis. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at 10%, 5% and 1%,

respectively.

Errores estándar en paréntesis. *, **, y *** indican significancia estadística al 10%, 5% y 1%,

respectivamente.

Columns (1) and

(4) show that leased land has significantly higher technical and allocative

inefficiency costs than owned land (baseline). Regarding sharecropping, the

results indicate that this tenure arrangement is statistically more

cost-efficient than the ownership system, consistent with previous findings.

This efficiency could be related to the fact that sharecropping is based on a

contract in which the sharecropper’s salary is linked to the farm’s performance

and, in many cases, is made in kind. Therefore, the sharecropper’s earnings are

directly related to his performance. This relationship between performance and

profits in sharecropping can foster greater efficiency in resource allocation,

as both the owner and sharecropper have a shared interest in maximizing farm

productivity. Combining the landowner’s experience and knowledge with the

sharecropper’s labor could result in greater efficiency than other land tenure

systems.

The estimated

coefficients for the land variable suggest that more extensive landholdings are

more inefficient, the relationship being non-linear, but decreasing. Although

not significant, this result is in line with other findings for the

agricultural sector (15, 30, 43). The

specialization coefficient indicates that farmers who allocate a larger

proportion of the farm to rice production have significantly lower inefficiency

costs. As suggested by Jaime and Salazar (2011),

this result indicates that farmers who specialize in rice cultivation tend to

have some advantages in productivity, compared to farmers who diversify and

devote their land to other kinds of crops. Education is included in columns (2)

and (5) to control for farmer-level heterogeneities. Again, the sharecropping

coefficient is only significant in explaining allocative inefficiency costs.

The estimated coefficients for leasing and weeding decrease when compared to

the results in columns (1) and (4). In the first case, the drop is between 12.7%

and 24.9%, while in the second case, it is between 13.7% and 12.7%. This

indicates that when controlling for the farmer’s educational level, the tenure

arrangement’s effect tends to be more favorable in terms of inefficiency costs.

This finding could be related to the fact that better educated farmers have

better access to information on good agricultural practices, technical advice and

training programs, subsidies, or new production technologies, all of which have

a positive impact on efficiency. However, note that the education coefficient

is positive and statistically significant for the allocative inefficiency cost,

which is not expected but is in line with the findings of Henderson

(2015) and Vasconcelos (2020). It is reasonable to think that farmers with

higher educational attainment face higher opportunity costs in their occupational

choice and may see a reduced effort in rice production due to less reliance on farming

for income generation.

Columns (3) and

(6) include experience as a determinant of inefficiency cost and commune fixed

effects. In inefficiency costs, the coefficients for tenure arrangements change

slightly, implying that commune-specific market characteristics and imperfections

appear to be unimportant in driving the relationship between land tenure and

inefficiency costs. This result makes sense given that the communes of Ñiquén

and San Carlos are in the Ñuble region and only 33 km apart, implying that

there are unlikely to be significant differences in the land market, productive

infrastructure, accessibility to inputs, and employment opportunities that

contribute significantly to reducing technical and allocative inefficiency costs

in each land tenure arrangement.

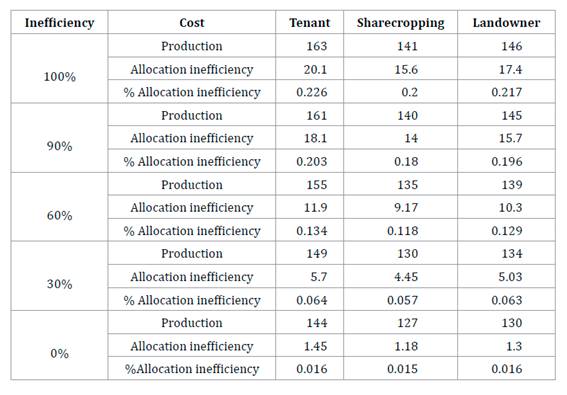

Finally, it is

studied how rice production costs could change with an improvement in the

allocation of land input, using current costs as a benchmark. Table

8, partially reproduces the results of table 5 and

incorporates the estimated costs for different levels of inefficiency.

Table

8. Production costs under different levels

of inefficient land allocation.

Tabla 8. Costos

de producción bajo diferentes niveles de asignación ineficiente de la tierra.

Relative to

benchmark, a 40% efficiency improvement potentially reduces allocation costs by

40.8% for leasehold and ownership and by 41.2% for sharecropping. This leads to

an average decrease of 4%-5% in production costs and an increase of 17.8%,

11.2% and 12.9%, and in profits for leasehold, sharecropping, and ownership,

respectively. The last three rows of the table show costs when land allocation

is efficient relative to cash input. Costs of 1.5%-1.6% due to inefficient

allocation of labor and other inputs remain. This finding suggests that about

93% allocation costs are associated with deficiencies in land use, particularly

the underutilization of input relative to the numeraire. The potential impact

on profits is considerable. The leased land is the most favored with 49.1%

increase in earnings. On the other hand, sharecropping and ownership could

increase their profits by 25.3% and 29.8%, respectively. These results are

intuitive as they demonstrate the monetary impact of efficiency; allow us to

understand that there are significant differences depending on the land tenure

arrangement; and highlight the need for public policies encouraging the

efficient use of productive factors.

Conclusions

This paper

empirically investigated how agricultural land ownership, sharecropping, and

leasing regimes may affect production cost efficiency. For this purpose, a

sample of 107 rice producers from the Ñuble Region in Chile, observed from 2014

to 2015, was used, and a stochastic frontier model of costs was estimated using

the primal system approach. This allowed estimating misallocation measures for

productive factors, technical and allocative efficiency scores, and decomposing

production costs into three components: frontier costs, costs due to technical

inefficiency, and costs due to allocative inefficiency.

The results

revealed that, on average, inefficiency increases rice production costs by 82%.

Of this increase, 61% was attributed to technical inefficiency, while 21% was

due to costs due to allocative inefficiency. Regarding the latter costs,

statistically significant differences were found among the various land tenure

regimes. In particular, the sharecropping system stood out as the most

efficient, with production costs 13.5% lower than the rental system and 3.4%

lower than those of the ownership system.

The finding may

be connected to sharecropping’s potential benefits over land ownership and

leasing systems as a production organization system, particularly regarding

higher labor productivity and reduced labor and supervision costs. One of the

critical factors in this regard is that, in contrast to the time-based wage

that is more typical in land ownership and leasing systems, sharecropping in

Chile is based on a performance-linked incentive structure. Sharecroppers have

a higher incentive to exert more effort and complete all responsibilities more

efficiently, which can cut down on or do away with the costs associated with supervisión

that are typical in wage labor systems. This is because sharecropping

agreements frequently entail a more equitable distribution of risks and

benefits between the landowner and the farmer, which can benefit the farmer and

the farm from an economic perspective.

An additional

relevant finding is that, regardless of the land tenure regime, a public policy

that addresses the misallocation of the productive factor of land among farms

could potentially reduce up to 93% of the costs associated with inefficient

allocation per kilogram of rice. This would substantially impact farmers’

profits and, consequently, wealth generation in the rice industry. According to

estimates, improving land use efficiency would result in significant,

cross-sectional profit increases for all land tenure types.

This study

provides valuable data on the efficiency of rice production. It highlights

differences in cost efficiency levels according to land tenure type. It

suggests that these differences may be related to the potential of each tenure

system to ensure better farm yields. It also highlights the need for public

policies that promote a better allocation of productive resources for the whole

sector’s benefit. A limitation of this study is assuming that all farmers,

regardless of tenure type, have the same skills for working the land. In this

sense, relaxing this assumption could solve input misallocation by

redistributing them from less to more skilled farmers so that optimum marginal

productivities are equated. The latter could be a topic for future research on

the particular case of Ñuble Region in Chile.

1. Ackerberg, D.

A.; Botticini, M. 2000. The choice of agrarian contracts in early renaissance

Tuscany: Risk sharing, moral hazard, or capital market imperfections?

Explorations in economic history. 37(3): 241-257.

2. Ahmed, M.;

Billah, M. 2018. Impact of sharecropping on rice productivity in some areas of

Khulna district. Bangladesh Journal of Agricultural Research. 43(3): 417-430.

3. Alem, H.;

Lien, G.; Hardaker, J. B. 2018. Economic performance and efficiency

determinants of crop-producing farms in Norway. International Journal of

Productivity and Performance Management.

4. Asmara, R.

2017. Technical, cost and allocative efficiency of rice, corn and soybean

farming in Indonesia: Data envelopment analysis approach. Agricultural Socio-Economics

Journal. 17(2): 76.

5. At, C.;

Thomas, L. 2019. Optimal tenurial contracts under both moral hazard and adverse

selection. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 101(3): 941-959.

6. Atkinson, S.

E.; Dorfman, J. H. 2006. Chasing absolute cost and profit savings in a world of

relative inefficiency. Technical report.

7. Battese, G.

E.; Coelli, T. J. 1988. Prediction of firm-level technical efficiencies with a

generalized frontier production function and panel data. Journal of

econometrics. 38(3): 387399.

8. Benencia, R.;

Quaranta, G. 2001. El papel de la mediería en el agro moderno. Producción de

leche y hortalizas en la Pampa Húmeda bonaerense. Revista Interdisciplinaria de

Estudios Agrarios. 15: 123-151.

9. Berisso, O.

2019. Analysis of factors affecting persistent and transient inefficiency of

Ethiopia’s smallholder cereal farming. In Efficiency, equity and well-being in

selected African countries. 199-228. Springer.

10. Bolhuis, M.

A.; Rachapalli, S. R.; Restuccia, D. 2021. Misallocation in Indian agriculture.

Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

11. Chen, C.

2017. Untitled land, occupational choice, and agricultural productivity.

American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics. 9(4): 91-121.

12. Chen, C.;

Restuccia, D.; Santaeulàlia-Llopis, R. 2022. The effects of land markets on

resource allocation and agricultural productivity. Review of Economic Dynamics.

45: 41-54.

13. Coelli, T.;

Rahman, S.; Thirtle, C. 2002. Technical, allocative, cost and scale

efficiencies in Bangladesh rice cultivation: a non-parametric approach. Journal

of Agricultural Economics. 53: 607-626.

14. FAO. 2022.

Food outlook - biannual report on global food markets. https://doi . org/10.4060/cc2864en. Access 07-12-2022.

15. Gautam, M.;

Ahmed, M. 2019. Too small to be beautiful? The farm size and productivity

relationship in Bangladesh. Food Policy. 84: 165-175.

16. Gligo V.;

Nicolo. Universidad de Chile. Facultad de Ciencias Agronómicas. 2021. Reforma

Agraria Chilena: causas, fases y balance. Universidad de Chile.

https://bibliotecadigital.ciren.cl/handle/20.500.13082/32913

17. González, J.

2018. El cultivo del arroz. En Historia de Linares. Municipalidad de Linares,

Academia Chilena de la Historia. 663-669.

18. Henderson,

H. 2015. Considering technical and allocative efficiency in the inverse farm

sizeproductivity relationship. Journal of Agricultural Economics. 66(2):

442-469.

19. Houngue, V.;

Nonvide, G. M. A. 2020. Estimation and determinants of efficiency among rice

farmers in Benin. Cogent Food & Agriculture. 6(1): 1819004.

20. INE. 2007.

Cambios estructurales en la agricultura chilena, análisis intercensal

1976-1997-2007.

htps://www.ine.gob.cl/docs/default-source/censo-agropecuario/publicacionesyanuarios/2007/cambios-estructurales-en-la-agricultura-chilena---analisisintercens

al-1976-1997-2007. pdf?sfvrsn=9dfd0a74_7. Access

13-12-2022.

21. INE. 2022.

Síntesis agropecuaria encuestas intercensales 2021-2022. https://www.

ine.gob.cl/docs/default-source/siembra_y_ cosecha/publicaciones-y-anuarios/s%C3%ADntesis-agropecuaria/s%C3%ADntesis-agropecuaria---encuestas-intercensales-agropecuarias-2021-2022.pdf.

Access 13-12-2022.

22. Islam, M.

A.; Fukui, S. 2018. The influence of share tenancy contracts on the cost

efficiency of rice production during the Bangladeshi wet season. Economics

Bulletin. 38(4): 2431-2443.

23. Jacoby, H.

G.; Mansuri, G. 2009. Incentives, supervision, and sharecropper productivity.

Journal of Development Economics. 88(2): 232-241.

24. Jaime, M.

M.; Salazar, C. A. 2011. Participation in organizations, technical efficiency

and territorial differences: A study of small wheat farmers in Chile. Chilean

Journal of Agricultural Research. 71(1): 104.

25. Jamal, E.;

Dewi, Y. A. 2009. Technical efficiency of land tenure contracts in West Java province,

Indonesia. Asian Journal of agriculture and development. 6(1362-2016-107667):

21-33.

26. Kamau, P. N.

2019. Technical, economic and allocative efficiency among maize and rice

farmers under different land-use systems in east African wetlands. Technical

report.

27. Kumbhakar,

S. C.; Wang, H. J. 2006. Estimation of technical and allocative inefficiency: A

primal system approach. Journal of Econometrics. 134(2): 419-440.

28. Kumbhakar,

S. C.; Mydland, O.; Musau, A.; Lien, G. 2020. Disentangling costs of persistent

and transient technical inefficiency and input misallocation: The case of

Norwegian electricity distribution firms. The Energy Journal. 41(3).

29. Lien, G.;

Kumbhakar, S. C.; Alem, H. 2018. Endogeneity, heterogeneity, and determinants

of inefficiency in Norwegian crop-producing farms. International Journal of

Production Economics. 201: 53-61.

30. Masterson,

T. 2007. Productivity, technical efficiency, and farm size in Paraguayan

agriculture.

31. Musau, A.;

Kumbhakar, S. C.; Mydland, Ø.; Lien, G. 2021. Determinants of allocative and

technical inefficiency in stochastic frontier models: An analysis of Norwegian

electricity distribution firms. European Journal of Operational Research.

288(3): 983-991.

32. ODEPA. 2015.

Boletín del arroz. https://wWw.odepa.gob.cl/contenidos-rubro/

boletinesdelrubro/boletin-del-arroz-mayo-de-2015. Access 10-11-2022.

33. ODEPA. 2017.

La cadena del arroz en Chile.

https://www.odepa.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/ARROZ2018Final.pdf. Access

05-09-2023.

34. ODEPA. 2019.

Panorama de la agricultura chilena. https://www.

odepa.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/panorama2019Final.pdf. Access

13-12-2022.

35. ODEPA. 2020.

Arroz: temporada 2019/20 - 2020/21. https://bibliotecadigital.odepa.

gob.cl/bitstream/handle/20.500.12650/70425/Articulo-arroz.pdf. Access

07-12-2022.

36. ODEPA. 2022.

Boletín de cereales.

https://bibliotecadigital.odepa.gob.cl/bitstream/handle/20.500.12650/71857/BCereales082022

.pdf. Access 07-12-2022.

37. Okello, D.

M.; Bonabana-Wabbi, J.; Mugonola, B. 2019. Farm level allocative efficiency of

rice production in Gulu and Amuru districts, northern Uganda. Agricultural and

Food Economics. 7(1): 1-19.

38. Paredes C.,

M.; Becerra V., V.; Doñoso Ñ., G. 2021. Desafíos para el cultivo del arroz en

chile para la próxima década. https://biblioteca.inia.cl/bitstream/handle/20.500.14001/68052/Capitulo%20X.pdf?sequence=22&isAllowed=y.

Access 23-11-2022.

39. Pi, J. 2013.

A new solution to the puzzle of fifty-fifty split in sharecropping. Economic research

Ekonomska istraživanja. 26(2): 141-152.

40. Posada, M.

G. 1995. La articulación entre formas capitalistas y no capitalistas de

producción agrícola. El caso. Agricultura y Sociedad. 77: 9-40.

41. Quijada, F.;

Salazar, C.; Cabas, J. 2022. Technical efficiency, production risk and

sharecropping: The case of rice farming in Chile. Latin American Economic

Review. 31: 1-16.

42. Schmidt, P.;

Lovell, C. K. 1979. Estimating technical and allocative inefficiency relative

to stochastic production and cost frontiers. Journal of econometrics . 9(3):

343-366.

43. Sheng, Y.;

Ding, J.; Huang, J. 2019. The relationship between farm size and productivity

in agriculture: Evidence from maize production in northern China. American Journal

of Agricultural Economics . 101(3): 790-806.

44. Tasila Konja,

D.; Mabe, F. N.; Alhassan, H. 2019. Technical and resource-use-efficiency among

smallholder rice farmers in northern Ghana. Cogent Food & Agriculture.

5(1): 1651473.

45.

Troncoso-Sepúlveda, R. 2019. Transmisión de los precios del arroz en Colombia y

el mundo. Lecturas de Economía. 91: 151-179.

https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.le.n91a05

46. Vasconcelos,

J. S. 2020. Tierra y derechos humanos en Chile: la contrarreforma agraria de la

dictadura de Pinochet y las políticas de reparación campesina. Historia agraria:

Revista de agricultura e historia rural. 80: 209-242.

Note

The

research belongs to the Internal Project 2230332 IF/R, Universidad del Bío-Bío.