Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 56(1). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2024.

Original article

Nutritional

quality of amaranth (Amaranthus) silage in response to forage airing and

addition of lactic bacteria

Calidad

nutricional de amaranto (Amaranthus) ensilado en respuesta a la

aireación del forraje y a la adición de bacterias lácticas

Julián Agustín

Repupilli1

Juan José

Gallego3

1Universidad

Nacional de Río Negro. Sede Atlántica. Don Bosco y Leloir s/n. Viedma (8500).

Río Negro. Argentina.

2Universidad

Nacional de Río Negro (UNRN-CONICET). CIT-RIO NEGRO Sede Atlántica. Don Bosco y

Leloir s/n. Viedma (8500). Río Negro. Argentina.

3Instituto

Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria (INTA). Estación Experimental Valle Inferior

de Río Negro. Ruta Nac. N° 3 km 971 - Camino 4 IDEVI (8500) Viedma. Río Negro.

Argentina.

Abstract

Climate change

is reducing forage availability for ruminants. Previous studies in Northern Patagonia,

Argentina, have demonstrated the adaptation of the amaranth crop to these agroclimatic

conditions under irrigation. Moreover, this crop is used as forage in marginal areas

of the world, given its outstanding productive and nutritional qualities. The

objective of this study was to evaluate the nutritional quality of amaranth

silage in response to previous wilting and the addition of lactic acid

bacteria. The crop was harvested at the milky grain stage and ensiled in

experimental microsilos for 60 days. Before ensiling, different treatments

(wilting and addition of lactic acid bacteria) were applied. Parameters related

to nutritional quality were evaluated, including ash, crude protein (CP),

neutral detergent fiber (NDF), acid detergent fiber (ADF), dry matter

digestibility (DMD), and metabolizable energy (ME). Simultaneous treatment with

air and the addition of lactic acid bacteria before ensiling resulted in the

best nutritional quality characteristics of the silage. The most significant

results were protein value of 12.7%, 41.1% NDF and 19.1% FDA. The DM and ME

were 74% and 2.67 Mcal/kg, respectively. Thus, amaranth silage can be

considered an alternative conserved forage for animal feed in this region.

Keywords: nutritional

value, amaranth, silage, inoculation, quality

Resumen

El cambio

climático está reduciendo la disponibilidad de forraje para los rumiantes. Estudios

previos en la Patagonia Norte Argentina demuestran la adaptación del cultivo de

amaranto a estas condiciones agroclimáticas bajo riego. Sin embargo, este cultivo

se utiliza como forraje en zonas marginales del mundo, dadas las destacadas

cualidades productivas y nutricionales del cultivo de amaranto. El objetivo de

este estudio fue evaluar la calidad nutricional del ensilado de amaranto en

respuesta al oreado previo del forraje y a la adición de bacterias lácticas. El

cultivo se cosechó en el estado grano lechoso y se ensiló en microsilos

experimentales durante 60 días. Antes del ensilado, se llevaron a cabo diferentes

tratamientos (oreado y adición de bacterias lácticas). Se evaluaron parámetros relacionados

con la calidad nutricional: cenizas, proteína cruda (PC), Fibra Detergente Neutro

(FDN), Fibra Detergente Ácido (FDA), digestibilidad de la materia seca (DMS) y energía

metabolizable (EM). El tratamiento simultáneo de oreado y adición de bacterias lácticas

antes del ensilado dio lugar a las mejores características de calidad

nutricional del ensilado obtenido. Los resultados más importantes bajo estas

condiciones fueron valores de proteína del 12,7%, FDN del 41,1% y FDA del

19,1%. La DMS y la EM fueron del 74% y 2,67 Mcal/kg, respectivamente. Así, el

ensilaje de amaranto puede ser considerado como una alternativa forrajera

conservada para la alimentación animal de la región.

Palabras claves:

valor

nutricional, amaranto, ensilado, inoculación, calidad

Originales: Recepción: 11/05/2023 - Aceptación: 29/02/2024

Introduction

The projected

growth in global food demand has led to an increased focus on underutilized crops,

with the potential to improve global food security and mitigate the adverse

effects of climate change. Animal production in the Lower Rio Negro Valley is

limited by a seasonal lack of forage. Feed and conserved fodder, such as

silage, ensures forage quality and quantity. The main silage resource in the

area is corn, with a biomass yield of over 30 t/ha and a protein content of 8%.

However, its cultivation requires 900 mm of water and 300 kg/ha of nitrogen (27). Amaranthus cruentus cv Mexicano has

shown adaptability to the local environmental conditions with yields of 21

t/ha, needing 800 mm and 150 kg/ha of water and nitrogen requirements,

respectively (39, 40, 41). Therefore,

amaranth could be an alternative forage resource for the region given its high

biomass production and low management requirements. Seguín

et al. (2013) stated that amaranth shows high rumen degradability

when used as animal feed, either by direct grazing or as conserved forage. The

nutritive value of this forage varies according to the developmental stage, standing

out for its high crude protein content (8-29%), low lignin values (1.7-7.3%),

and high in vitro digestibility (59-79%) (23,

28). However, high moisture and protein content could negatively

affect the ensiling process. According to Borreani et

al. (2018), moisture content produces effluents that reduce soluble

carbohydrates, whereas high protein values in the forage have a buffering

capacity and prevent pH decrease (<5.0) in the silage. A common practice to

decrease forage moisture is to wilt the forage in the field for 24-48 hours

under good weather conditions (no risk of rain) and with minimal mechanical

treatment. This increases dry matter, resulting in a higher concentration of

soluble carbohydrates that favors the fermentation process and nutritive value

(37). The use of additives, such as

bacterial inoculants, could favor a rapid decrease in pH, improving the

conservation and nutritive value of silage (4, 32).

Among the most commonly used inoculants are lactic acid bacteria (LAB), which

ferment carbohydrates into lactic acid, acidifying the silage and inhibiting growth

of undesirable bacteria (24), thus

improving the fermentation and aerobic stability of the final product. Although

silage techniques have been studied for this crop, different results depend on

variety, cutting time, processing methodology, and place of origin (16, 20, 28, 29). In South America, there is no

information on amaranth as fodder or its conservation in silage. In this study,

we hypothesized that wilting and LAB inoculation would improve fermentation

quality of amaranth forage. The objective of this study was to evaluate the

nutritional quality of amaranth silage in response to previous wilting of

forage and addition of lactic acid bacteria.

Materials

and methods

Site

location, climatic conditions, and forage production

Field

experiments were conducted at the INTA-Estación Experimental Agropecuaria Valle

Inferior del Río Negro (40°48’ S, 63°05’ W; 4 m). This area in Patagonia,

Argentina, has an irrigation system that covers 24,000 ha. During the growth

period of amaranth in 2019 (November to April), rainfall was 186 mm and the

average temperature was 19°C. The physicochemical characteristics of the upper

50 cm of the experimental loam soil were: pH (8.20); electrical conductivity

(1.2 mmhos cm-1); organic matter (3.8%); total nitrogen (0.18%);

N-NO3 (24.60 mg kg-1); P (Olsen, 16.60 mg kg-1);

S (14.7 mg kg-1 as a SO4=); Ca (8.230 mg kg-1);

Mg (1.170 mg kg-1); sodium-adsorption ratio (1.83). The INTA

laboratory performed the soil characterization.

The cultivar

evaluated was A. cruentus cv Mexicano, sown in rows with a horticultural

seeder at the end of spring (November 20th). The sowing area was 70

m2 (10 furrows 0.7 m wide × 10 m long). Weeding was performed

manually when the plants reached 20-30 cm in height; thinning was performed by

hand, leaving ten plants m-2. Furrow irrigation was applied

according to soil moisture retention curve before reaching the permanent

wilting point, with a total lamina of 800±50 mm. Fertilization with granulated

urea (46% N), with a nitrogen (N) dose of 90 ha-1, was carried out

in two stages; on plants 60 cm high and at bloom.

Treatment

of plant material before the silage process

The forage was

cut at advanced flowering stage (between milky-pasty grains), corresponding to

a chronological time of 123 days or 1627 growing degree days, with dry matter

(DM) values above 20%. Amaranth plants were manually cut 50 cm above the soil

surface (26) and then wilted in the field

for 24 hours before chopping the material. The plants were chopped using a

Thomas Willey mill until they reached a size of 1-3 cm. The chopped material

was then treated with lactic acid bacteria (LAB) under conditions recommended

by the manufacturer using an atomizer. (Bemix Plus® 2% w/v). Four different

types of silage were obtained: unwilted, ensiled amaranth (UWAE); unwilted,

ensiled amaranth with added lactic acid bacteria (UWAEL); wilted, ensiled

amaranth (WAE); and wilted, ensiled amaranth with added lactic acid bacteria

(WAEL).

Ensiling

process

The silage was

prepared at laboratory scale using 110mm PVC tubes 30 cm long, known as

experimental microsilage. The filling of the experimental microsilage was

performed by placing the plant material in compacted layers with a hydraulic

press (140 kgf) ensuring homogeneous compaction. The tubes were capped and

sealed to achieve anaerobic conditions (four replicates for each forage type).

The experimental microsilage was maintained under environmental conditions for 60

days.

Characterization

and chemical analyses of the forage and silage types

Chop size: A

fresh sample (100 g) of non-ensiled plant material was measured using a Vernier

caliper and grouped according to length. After the ensiling period, the average

temperature was determined with an infrared thermometer (AMPROBE IR-710) and a

simple (50 g) was collected at a depth of 15 cm from each silo. All samples

were frozen at -18°C until use for quality determination. An aqueous extract

(1:4) was made and left to rest for 1 h at room temperature, after which pH was

measured with a pH meter (Foodcare HI99161) (10).

Dry matter content (% DM) was determined according to the AOAC

(2000). The samples were ground using a grinder (ARCANO®). Ash content,

crude protein (CP%), Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF %), and Acid Detergent Fiber

(ADF %) were determined following the methodology proposed by the AOAC (2000). The dry matter digestibility (% DMD) was

estimated using the predictive equation proposed by Rohweder

et al. (1978). Metabolizable Energy (ME) was determined using the

following formula: EM: 3.61*DMD according to Di Marco

(2011). All measurements were performed in triplicate.

Statistical

analysis

A completely

randomized block design was used, with four treatments and four replicates for

each treatment. Pre-ensiling quality variables were analyzed using simple ANOVA

(WA-C; UWA-C). Silage quality parameters were analyzed by double ANOVA with the

following sources of variation: wilting (UWAE; WAE), inoculation (UWAEL; WAEL),

and their interaction as main effects (2 × 2 factorial design). The T° and pH

showed no interaction, while DM, CP, ash, NDF, and SDF were analyzed by simple

ANOVA to evaluate the effect of wilting and addition of lactic acid bacteria

separately. Comparisons of means were made using Fisher’s least significant

difference (LSD) test at 5%. Statistical analyses were performed using InfoStat

(8).

Results

and discussion

Pre-ensiling

characteristics of forage

Visual

differences in coloration between UWA-C and WA-C were observed in the chopped

plant material (data not shown). The latter had an opaque yellow-olive color, whereas

UWA-C was bright olive-green, which could be associated with the loss of water

during the wilting process. In addition, drying plant material in the sun

results in the formation of indigestible protein-carbohydrate complexes called

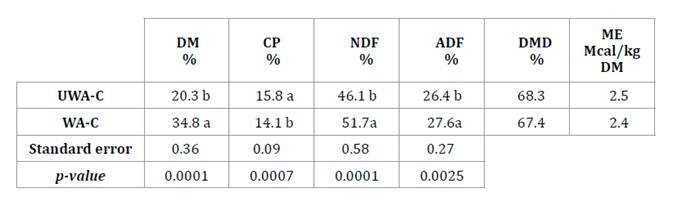

Maillard products. The DM values are presented in table 1.

Table

1. Nutritional parameters of unwilted

amaranth control (UWA-C) and wilted amaranth control (WA-C).

Tabla 1. Parámetros

nutricionales del forraje de amaranto no oreado control (UWA-C) y forraje de

amaranto oreado control (WA-C).

Dry matter (DM); Crude Protein (CP), Neutral

Detergent Fiber (NDF); Acid Detergent Fiber (ADF), Dry Matter Digestibility

(DMD), Metabolizable Energy (ME) associated with the quality of the forage

before silage. Values of the same variable followed by the same letter are not

statistically different according to Fisher’s LSD test (p > 0.05).

Materia Seca (MS); Proteína Cruda (PC), Fibra

Detergente Neutra (FDN); Fibra Detergente Ácida (FA), Digestibilidad de la

Materia Seca (DMS), Energía Metabolizable (EM) asociados a la calidad del

forraje antes del ensilaje. Los valores de las mismas variables seguidos de la

misma letra no son estadísticamente diferentes según la prueba LSD de Fisher (p

> 0,05).

Knowing the

proper DM content of forage at the pre-ensiling stage is essential to achieve

efficient compaction and an anaerobic environment while preventing growth of

undesirable microorganisms. DM content of 30-35% is usually recommended to

obtain high-quality amaranth silage (14).

Krawutschke et al. (2013) achieved an optimum

DM content of 30-35 % when wilting red clover (Trifolium pratense L.),

which like amaranth is difficult to ensile due to a lower water-soluble

carbohydrate concentration (WSC), higher buffering capacity (BC) and lower dry

matter (DM) content at harvest. In amaranth, wilting (WA-C) resulted in dry

matter values that reached the recommended values for silage; therefore,

wilting could favor a higher concentration of soluble carbohydrates and a lower

concentration of lactic acid (21).

On the other

hand, table 1, shows the nutritional parameters of the

material before the ensiling process and statistically significant differences

(p> 0.001) were observed between the UWA-C and WA-C treatments. Forage total

N determines the total amount of N available for animal consumption. In this

study, the %CP of UWA-C was higher than that of WA-C, possibly because the

drying process favors loosing nonstructural carbohydrates, volatile organic

substances, and protein degradation. This results in amino acids with higher

solubility that can be removed from plant tissues, and although this process

can significantly decrease the %CP, it varies depending on the drying method. N

decreased by only 5% in this case because of wilting conditions. WA-C had the

highest fiber content (NDF and SDF), possibly because exposure of the material

to ultraviolet radiation (wilting) decreased forage soluble components. In this

study, NDF content ranged from 46.1% to 51.7%, and FAD content ranged from

26.4% to 27% when amaranth plants were wilted. Fiber components, such as NDF,

FAD, and lignin, are generally inert during plant respiration, but their

concentrations increase because of a decrease in oxidized soluble compounds.

Therefore, slow-drying methods are expected to result in higher proportions of

NDF and FAD. The digestibility of UWA-C was significantly higher (p> 0.001)

than that of WA-C, mainly given by the lower fiber content of the undried plant

material.

On the other

hand, the size of the plant material obtained in this study before ensiling was

between adequate ranges (1-3 cm), coinciding with the recommendations of Citlak and Kilic (2020).

Determination

of parameters related to fodder processing and conservation

A double ANOVA

determined that the wilting and inoculation treatments did not affect the

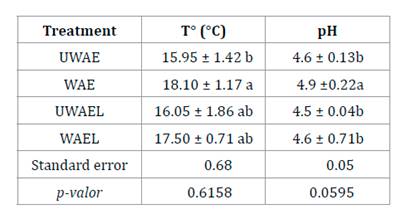

temperature and pH variables. However, as shown in table 2,

significant differences in T° were observed with the wilting effect, where the

minimum and maximum values (UWAE and WAE, respectively) were recorded, but

there were no differences in this parameter after LAB addition.

Table

2. Parameters related to fodder processing

and conservation.

Tabla 2. Parámetros

relacionados con el procesado y conservación del forraje.

Temperature (T°), and pH of the experimental

microsilage at the moment of opening for unwilted amaranth ensiled (UWAE);

unwilted amaranth ensiled with added lactic acid bacteria (UWAEL); wilted amaranth

ensiled (WAE); wilted amaranth ensiled with added lactic acid bacteria (WAEL).

Values of the same variable followed by the same letter are not statistically

different according to Fisher’s LSD test (p > 0.05).

Temperatura (T°), y pH de los microsilos

experimentales en el momento de apertura. Amaranto ensilado sin orear (UWAE);

amaranto ensilado oreado (WAE); amaranto ensilado sin orear con adición de

bacterias lácticas (UWAEL); amaranto ensilado oreado con adición de bacterias

lácticas (WAEL). Los valores de las mismas variables seguidos de la misma letra

no son estadísticamente diferentes según la prueba LSD de Fisher (p > 0,05).

Temperature

affected silage fermentation, and the best results were obtained with a

moderate T between 20 and 30°C. For corn silage, Zhou et

al. (2019), reported that increasing storage temperature from 5°C to

25°C did not affect fermentation profiles of most biochemical parameters or

bacterial and fungal populations. In the present study, the low temperatures

observed when opening the experimental microsilage could be related to low

ambient temperature at the study site.

When anaerobic

fermentation occurs in the silage process, lactic acid bacteria in the forage

are desirable because they rapidly lower the pH, achieve rapid stabilization,

and maintain the characteristics of the ensiled material (9, 36). The pH (average of 4.65) observed for all

silages was within the established values for good-quality silages, which is

comparable with the values reported for different amaranth varieties, harvest

stages, and place of cultivation (26).

Several factors may be responsible for silage having a higher than normal pH

(~4.0), including buffering capacity provided by high protein content (17). In UWAEL and WAEL, the use of bacterial

inoculants slightly increased acidity of the experimental microsilage. Similar

results have been obtained for corn, oats, and amaranth silages (4, 20). In alfalfa, a forage with high buffering

capacity, wilting pretreatment, and a pH of 5.19 was reported after 60 days of

ensiling (11). In this study, silage with

pre-wilting and higher DM (WA-C, table 1) showed a slight

increase in T° and pH; however, the silage obtained with wilted forage and

addition of lactic acid bacteria (WAEL) only showed a decrease in pH.

Other authors

have reported that lactic acid bacteria in temperate to cold environments favor

a lower pH and rapid production of desirable metabolites, such as lactic acid,

accelerating fermentation, and better-conserving silage nutrients over a wide

range of growth temperatures (4, 13).

Nutritional

quality of ensiled plant material

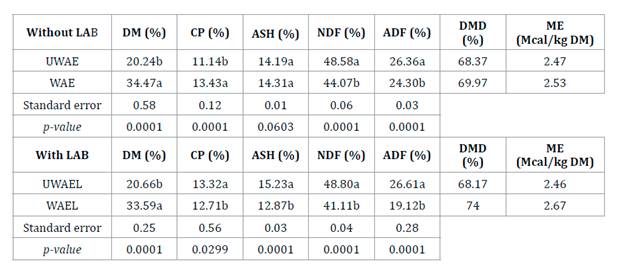

For the DM, CP,

Ash, NDF, and ADF variables, the double ANOVA detected interactions between

sources of variation (wilting and inoculation with LAB); therefore, the results

are presented separately (table 3).

Table

3. Parameters related to nutritional

quality.

Tabla 3. Parámetros

relacionados con la calidad nutricional.

Dry Matter (DM); Crude Protein (CP), Neutral

Detergent Fiber (NDF); Acid Detergent Fiber (ADF), Digestibility of Dry Matter

(DMD), Metabolizable Energy (ME) of ensiled plant material. Unwilted amaranth

ensiled (UWAE); wilted amaranth ensiled (WAE); unwilted amaranth ensiled with

added lactic acid bacteria (UWAEL); wilted amaranth ensiled with added lactic

acid bacteria (WAEL). Values of the same variable followed by the same letter

are not statistically different according to Fisher’s LSD test (p > 0.05).

Materia Seca (MS); Proteína Cruda (PC), Fibra

Detergente Neutra (FDN); Fibra Detergente Ácida (FDA), Digestibilidad de la

Materia Seca (DMS), Energía Metabolizable (EM)) del material vegetal ensilado.

Ensilado de amaranto sin orear (UWAE); ensilado de amaranto oreado (WAE);

ensilado de amaranto sin orear con adición de bacterias lácticas (UWAEL);

ensilado de amaranto oreado con adición de bacterias lácticas (WAEL). Los

valores de las mismas variables seguidos de la misma letra no son

estadísticamente diferentes según la prueba LSD de Fisher (p > 0,05).

When DM was

determined after the ensiling process, values of approximately 20% were

observed in the unwilted plant material (UWAE and UWAEL) and values approached

34% in the wilted material (WAE and WAEL). These values are similar to those

obtained before ensiling (table 1). Good fermentation results

in DM losses of less than 10% (3), and

the dry matter reduction was <1% in our case.

High protein

content is generally associated with higher forage quality, and protein content

has been reported to vary from 11.5 to 14% in amaranth silage (16). These variations could be associated with

on-site environmental conditions and agronomic practices affecting nutritional

composition (39). Table 3

shows protein content of the different silages used in this study, with values

within the mentioned range. Thus, UWAE had the lowest value (11.14%) for this

variable, whereas WAE had the highest value (13.43%). A decrease in protein

content of the ensiled material was observed when compared with the non-silage

forage (WA-C and UWA-C). The greatest decrease in protein content was observed

in UWAE (26% and 12% in UWAE and UWAEL, respectively); however, these decreases

were smaller in previously wilted forage (7% WAE and 10% WAEL). In general, a

higher osmotic pressure results from higher dry matter (DM) content, which

affects plant enzymatic activity and reduces proteolytic capacity (16, 30). This leads to a decrease in soluble

protein (CP) and an increase in the insoluble protein fraction, although the

latter is still potentially degradable in wilted silages (34, 35).

In contrast, the

addition of LAB to unwilted forage decreased proteolysis by 54% and CP loss

decreased. However, in the case of WAEL, the addition of LAB did not decrease

proteolysis, indicating an interaction between wilting and the addition of LAB,

reflected in a decrease in CP. These results agree with those published by Abbasi et al. (2018), who observed decreases in

protein content in relation to fresh material of 9%, 10%, and 7.5% in ensiled

forage, silage with lactic acid bacteria, and wilted forage, respectively.

Ash contents of

the different experimental microsilages is listed in table 3.

The silages with BL (UWAEL and WAEL) had the highest and lowest ash values,

respectively. However, silages without the addition of lactic acid bacteria

(UWAE-WAE) did not show statistically significant differences (p>0.05), and

the wilting process did not affect ash content. Amaranth species are

characterized by high mineral content that can vary according to variety,

harvest time, climate, soil, and crop management (39).

The ash values obtained were within the range of those published by other

authors for amaranth silage, which provides more minerals for livestock (25, 28). Seguín et al. (2013)

reported that the major mineral in amaranth is Ca, generally found as calcium

carbonate, and a fermentation process can favor the forage buffering capacity

to the detriment of its acidification.

Fibers in a feed

consist of structural carbohydrates in the cell walls and soluble or

nonstructural carbohydrates. Concerning fiber content of fresh chopped forages

(UWA-C and WA-C), the ensiling process reduced the NDF and ADF values, in

agreement with previous reports (16, 20, 25).

Fiber values in the silages obtained (table 3) were within

the ranges described in the literature for this crop (NDF: 28-47.7% and ADF:

26-31%) (14, 21). ADF and NDF showed

statistically significant differences due to the effect of wilting, and a

decrease was observed as a consequence. However, the addition of LAB further

favored this decrease in ADF and NDF. Similar results have been reported for

amaranth under similar conditions (wilting and addition of LAB) (1). However, in our study on unwilted silages, no

such decrease was observed. The higher moisture content and lower temperature

of the experimental microsilage in UWAE and UWAEL may have limited the

fermentation process and decreased the action of cellulolytic bacteria

responsible for the reduction in the fibrous fraction (14, 38). Fiber content is directly related to

digestibility and influences the rate at which feed passes through the

digestive tract of an animal (18).

Digestibility values for UWAE and UWAEL mirrored those observed for FDN and

FAD, and the addition of LAB did not increase this parameter. However, WAE and

WAEL showed higher digestibility and metabolizable energy values (table

3). A synergistic effect was observed between wilting and the addition of

LAB, achieving silage with a digestibility of 74.02%. This silage would be

classified as good quality according to Di Marco’s classification (7), whereas the rest of the silages would be of

medium quality. Regarding the ME of WAEL (2.67 Mcal/k DM), an 8% increase was

observed with respect to the non-silage plant material (WA-C). This energy

value can be expressed as 11.17 MJ/k DM and is within the range determined for

silages of other amaranth species (1, 29).

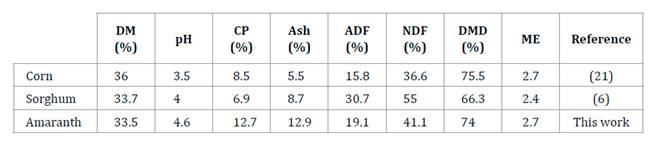

Based on the results obtained in this study, we can conclude that WAEL

presented the best organoleptic, conservation, and nutritional characteristics

among the four silages evaluated. By comparing the quality of this silage with

the values described for crops traditionally used in this type of conservation

technique (table 4), we can infer that it is comparable to

the quality of corn silage.

Table

4. Comparison of nutritional quality

parameters of the main crops used as fodder.

Tabla 4. Comparación

de los parámetros de calidad nutricional de los principales cultivos utilizados

como forraje.

Dry Matter (DM); pH; Crude Protein (CP), Ashes; Acid

Detergent Fiber (ADF), Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF); Digestibility of Dry

Matter (DMD), Metabolizable Energy (ME).

Materia seca (MS); pH; Proteína Cruda (PC), Cenizas;

Fibra Detergente Ácida (FDA); Fibra Detergente Neutra (FDN); Digestibilidad de

la Materia Seca (DMS), Energía Metabolizable (EM).

Likewise, it is

evident that amaranth protein content did not affect the ensiling process, and

its digestibility was comparable to that of corn silage. Regarding corn biomass

production for silage, previously reported values in the Lower Rio Negro Valley

vary between 16-34 Tn DM/ha, depending on the hybrid and management (19). In this sense, amaranth yields (7.8-21 Tn

DM/ha) were comparable to those of corn (39).

Conclusion

Wilting and

inoculation of amaranth forage with lactic acid bacteria before ensiling

resulted in silage with nutritional characteristics (crude protein percentage,

fiber content, dry matter digestibility, and metabolizable energy) that can be

classified as a high-quality component of animal diets. The practice of

ensiling amaranth as an alternative for conserving forage can be considered

viable in semi-arid regions such as Patagonia. However, further research under in

vivo conditions is required, especially regarding animal responses

according to category and species, as well as the exploration of combinations

with other ingredients to achieve complementarity and a better balance of

nutrients and energy.

Acknowledgements,

financial support and full disclosure

Financial

support from the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas

(CONICET), Universidad Nacional de Río Negro is gratefully acknowledged. The

authors thank to INTA Valle Inferior del Río Negro for the possibility to

conduct this study. Authors assures there is no actual or potential conflict of

interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people

or organizations.

1. Abbasi, M.;

Rouzbehan, Y.; Rezaei, J.; Jacobsen, S. E. 2018. The effect of lactic acid

bacteria inoculation, molasses, or wilting on the fermentation quality and

nutritive value of amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriaus) silage. Journal

of animal science. 96(9): 3983-3992. https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/sky257.

2. AOAC.

Official Methods of Analysis. 2000. 17th ed. The Association of Official

Analytical Chemists Gaithersburg MD USA.

3. Borreani, G.;

Tabacco, E.; Schmidt, R. J.; Holmes, B. J.; Muck, R. E. 2018. Silage review:

Factors affecting dry matter and quality losses in silages. Journal of Dairy

Science. 101(5): 3952-3979.

4. Chen, L.;

Bai, S.; You, M.; Xiao, B.; Li, P.; Cai, Y. 2020. Effect of a low temperature

tolerant lactic acid bacteria inoculant on the fermentation quality and

bacterial community of oat round bale silage. Animal Feed Science and

Technology. 269: 114669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2020.114669.

5. Citlak, H.;

Kilic, U. 2020. Innovative Approaches in Covering Materials Used in Silage

Making. International Multilingual. Journal of Science and Technology. 5:

2046-2050. http://www.imjst.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/IMJSTP29120390.pdf

6. De León, M.;

Giménez, R. A. 2011. Ensilajes de sorgo y maíz: rendimiento, composición, valor

nutritivo y respuesta animal. https://inta.gob.ar/sites/default/files/ scripttmp-ensilajes_de_sorgo_y_maz_rendimiento_composicin_va.pdf

(February 2018).

7. Di Marco, O.

2011. Estimación de calidad de los forrajes. Producir XXI. 20(240): 24-30.

https://www.produccion-animal.com.ar/tablas_composicion_alimentos/45-calidad.pdf

8. Di Rienzo, J.

A. InfoStat versión 2020. UNC Argentina.

9. dos Santos,

A. P. M; Santos, E. M.; Silva de Oliveira, J.; Garcia Leal de Araújo, G.; de

Moura Zanine, A.; Araújo Pinho, R. M.; Costa do Nascimento, T. V.; Fernandes

Perazzo, A.; Ferreira, D. de J.; da Silva Macedo, A. J.; de Sousa Santos, F. N.

2023. PCR identification of lactic acid bacteria populations in corn silage

inoculated withlyophilised or activated Lactobacillus buchneri. Revista de la

Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza.

Argentina. 55(1): 115-125. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.101

10. Faithfull,

N. T. 2002. Methods in Agricultural Chemical Analysis: A Practical Handbook.

CAB International. 304 p.

11. Huo, W.;

Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Shen, C.; Chen, L.; Liu, Q.; Guo, G. 2022. Effect of

lactobacilli inoculation on protein and carbohydrate fractions, ensiling

characteristics and bacterial community of alfalfa silage. Frontiers in

Microbiology. 13: 1070175.

12. Krawutschke,

M.; Thaysen, J.; Weiher, N.; Taube, F.; Gierus, M. 2013. Effects of inoculants

and wilting on silage fermentation and nutritive characteristics of red clover

grass mixtures. Grass and Forage Science. 68: 326-338.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2494.2012.00892.x

13. Kung, J. L.;

Shaver, R. D.; Grant, R. J.; Schmidt, R. J. 2018. Silage review Interpretation

of chemical, microbial, and organoleptic components of silages. Journal of

Dairy Science. 101: 4020-4033. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2017-13909

14. Liu, Q.;

Zong, C.; Dong, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhu, J.; Li, J.; Shao, T. 2020. Effects of

cellulolytic lactic acid bacteria on the lignocellulose degradation, sugar

profile and lactic acid fermentation of highmoisture alfalfa ensiled in

low-temperature seasons. Cellulose. 27: 7955-7965. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-020-03350-z

15. Liu, Y. F.;

Qiu, H. R.; Yu, X.; Sun, G. Q.; Ma, J.; Zhang, D. L.; Senbati, H. 2017. Effects

of addition of lactic acid bacteria, glucose, and formic acid on the quality of

Amaranthus hypochondriacus silage. Acta Prataculturae Sinica. 26:

214-220. DOI: 10.11686/cyxb2017164

16. Lotfi, S.;

Rouzbehan, Y.; Fazaeli, H.; Feyzbakhsh, M. T.; Rezaei, J. 2022. The Nutritional

Value and Yields of Amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus) Cultivar

Silages Compared to Silage from Corn (Zea mays) Harvested at the Milk

Stage Grown in a Hot-humid Climate. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 289:

115336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2022.115336

17. McDonald,

P.; Henderson, A. R.; Heron, S. J. E. 1991. The biochemistry of silage.

Chalcombe publications.

18. Mertens, D.

R.; Grant, R. J. 2020. Digestibility and intake. Forages: the science of

grassland agriculture. 2: 609-631. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119436669.ch34

19. Miñon, D.

P.; Gallego, J. J.; Barbarossa, R. A.; Margiotta, F. A.; Martinez, R. S.;

Reinoso, L. 2009. Evaluación de la producción de forraje de híbridos de maíz

para silaje en el Valle Inferior del Río Negro (campaña 2008-2009). INTA EEA

Valle Inferior.

20. Mu, L.; Xie,

Z.; Hu, L.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Z. 2021. Lactobacillus plantarum and

molasses alter dynamic chemical composition, microbial community, and aerobic

stability of mixed (amaranth and rice straw) silage. Journal of the Science of

Food and Agriculture. 101: 5225-5235. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.11171

21. Patterson, J.

D.; Sahle, B.; Gordon, A. W.; Archer, J. E.; Yan, T.; Grant, N.; Ferris, C. P.

2021. Grass silage composition and nutritive value on Northern Ireland farms

between 1998 and 2017. Grass Forage Science. 76: 300-308.

https://doi.org/10.1111/gfs.12534

22. Pineda, J.

A.; Sánchez, M. E.; Scaramuzza, J. P. 2015. Estudio comparativo de calidad y

valor nutritivo de silos bolsa de maíz en la zona de James Craik-Córdoba

(Bachelor’s thesis).

23. Pisarikova

B.; Peterka, J.; Trckova, M.; Moudry, J.; Zraly, Z.; Herzig, I. 2007. The

content of insoluble fibre and crude protein value of the aboveground biomass

of Amaranthus cruentus and A. hypochondriacus. Czech Journal of

Animal Science. 52: 348-353. DOI:10.17221/2339-CJAS

24. Queiroz, O.

C. M.; Arriola, K. G.; Daniel, J. L. P.; Adesogan, A. T. 2013. Effects of 8

chemical and bacterial additives on the quality of corn silage. Journal of

Dairy Science. 96(9): 5836-5843.

25. Rahjerdi, N.

K.; Rouzbehan, Y.; Fazaeli, H.; Rezaei, J. 2015 Chemical composition,

fermentation characteristics, digestibility, and degradability of silages from

two amaranth varieties (Kharkovskiy and Sem), corn, and an amaranth-corn

combination. Journal of Animal Science. 93: 5781-5790.

https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2015-9494

26. Ramírez

Ordóñes, S.; Rueda, J. A.; Medel Contreras, C. I.; Hernández Bautista, J.;

Corral Luna, A.; Portillo, M. F. 2023. Effect of cutting height, a bacterial

inoculant and a fibrolytic enzyme on corn (Zea mays L.) silage quality.

Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo.

Mendoza. Argentina. 55(2): 129-140. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.115

27. Reinoso, L.

G.; Martinez, R. S.; Otegui, M. E.; Mercau, J.; Gutierrez, M. 2018. Rendimiento

potencial de maíz en los valles de Norpatagonia: una aproximación desde los

modelos de simulación.

28. Rezaei, J.;

Rouzbehan, Y.; Fazaeli, H. 2009 Nutritive value of fresh and ensiled amaranth (Amaranthus

hypochondriacus) treated with different levels of molasses. Animal Feed

Science and Technology. 151: 153-160.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2008.12.001

29. Rezaei, J.;

Rouzbehan, Y.; Fazaeli, H.; Zahedifar, M. 2014. Effects of substituting

amaranth silage for corn silage on intake, growth performance, diet

digestibility, microbial protein, nitrogen retention and ruminal fermentation

in fattening lambs. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 192: 29-38.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2014.03.005

30. Rohweder,

D.; Barnes, R. F.; Jorgensen, N. 1978. Proposed hay grading standards based on

laboratory analyses for evaluating quality. Journal of Animal Science. 47:

747-759. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas1978.473747x

31. Seguin, P.;

Mustafa, A. F.; Donnelly, D. J.; Gélinas, B. 2013. Chemical composition and

ruminal nutrient degradability of fresh and ensiled amaranth forage. Journal of

the Science of Food and Agriculture. 93(15): 3730-3736.

32. Silveira

Pimentel, P. R.; dos Santos Brant, L. M.; Vasconcelos de Oliveira Lima, A. G.;

Costa Cotrim, D.; Costa Nascimento, T. V.; Lopes Oliveira, R. 2022. How can

nutritional additives modify ruminant nutrition? Revista de la Facultad de

Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 54(1):

175-189. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.076

33. Slottner,

D.; Bertilsson, J. 2006. Effect of ensiling technology on protein degradation

during ensilage. Animal feed science and technology. 127(1-2): 101-111.

34. Tamminga,

S.; Ketelaar, R.; Van Vuuren, A. M. 1991. Degradation of nitrogenous compounds

in conserved forages in the rumen of dairy cows. Grass and Forage Science.

46(4): 427-435.

35. Verbič, J.;

Ørskov, E. R.; Žgajnar, J.; Chen, X. B.; Žnidaršič-Pongrac, V. 1999. The effect

of method of forage preservation on the protein degradability and microbial

protein synthesis in the rumen. Animal feed science and technology. 82(3-4):

195-212.

36. Villa, R.;

Rodriguez, L. O.; Fenech, C.; Anika, O. C. 2020. Ensiling for anaerobic

digestion: A review of key considerations to maximise methane yields. Renewable

and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 134: 110401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2020.110401

37. Wan, J. C.;

Xie, K. Y.; Wang, Y. X.; Liu, L.; Yu, Z.; Wang, B. 2021. Effects of wilting and

additives on the ensiling quality and in vitro rumen fermentation

characteristics of sudangrass silage. Animal Bioscience. 34(1): 56. DOI:

10.5713/ajas.20.0079

38. Zhou, Y.;

Drouin, P.; Lafrenière, C. 2019. Effects on microbial diversity of fermentation

temperatura (10°C and 20°C), long-term storage at 5°C, and subsequent warming

of corn silage. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences. 32: 1528.

DOI:10.5713/ajas.18.0792

39. Zubillaga,

M. F.; Camina, R.; Orioli, G. A.; Barrio, D. A. 2019. Response of Amaranthus

cruentus cv Mexicano to nitrogen fertilization under irrigation in the

temperate, semiarid climate of North Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of plant

nutrition. 42: 99-110. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904167.2018.1549674

40. Zubillaga,

M. F.; Camina, R.; Orioli, G.; Failla, M.; Barrio, D. A. 2020. Amaranth in

southernmost latitudes: plant density under irrigation in Patagonia, Argentina.

Revista Ceres. 67: 93-99. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-737X202067020001

41. Zubillaga,

M. F.; Martínez, R. S.; Camina, R.; Orioli, G. A.; Failla, M.; Alder, M.;

Barrio, D. A. 2021. Amaranth irrigation frequency in northeast Patagonia,

Argentina. Biotechnologie, Agronomie, Société et Environnement. 25: 247-258.

DOI: 10.25518/1780-4507.19310