Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 55(2). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2023.

Original article

Effect of yeast

and mycorrhizae inoculation on tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) production

under normal and water stress conditions

Efecto

de la inoculación con levaduras y micorrizas sobre la producción de tomate (Solanum

lycopersicum) en condiciones normales y de estrés hídrico

Fontenla Sonia 1

Solans Mariana 3

1 Laboratorio de Microbiología Aplicada y Biotecnología. Centro

Regional Universitario Bariloche (CRUB). UNCO.

2 IPATEC. Universidad Nacional del Comahue. CONICET.

3 INIBIOMA. Universidad Nacional del Comahue. CONICET. Quintral

1250. Bariloche (8400) Rio Negro, Argentina.

* micaelaboenel@comahue-conicet.gob.ar

Abstract

The integration of

beneficial microorganisms into agricultural systems can improve crop resistance

to stress and increase yields. We studied tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) production

in a greenhouse experimental trial over a complete growing season. The experimental

design involved three factors: irrigation condition (normal/low), addition of

the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi Funneliformis mosseae (with/without),

and inoculation with four native soil yeasts (Candida aff. ralunensis; Candida

sake; Lachancea nothofagi and Candida oleophila). Co-inoculation

of F. mosseae and yeasts did not affect the tomato plants. Addition of F.

mosseae increased mycorrhizal colonization and production variables

regardless of irrigation level; however, its effects on growth were variable.

None of the inoculated yeasts increased mycorrhizal colonization. C. aff. ralunensis and C. oleophila inoculation

increased stem diameter under all conditions studied. C. aff. ralunensis inoculation enhanced fruit set and the

fruit/flower ratio under normal irrigation conditions, while C. sake inoculation

increased the fruit/flower ratio under low irrigation conditions. Arbuscular

mycorrhizae inoculation is presented as a beneficial production strategy to

increase plant tolerance and improve water use. We propose that C. aff. ralunensis and C. oleophila inoculation improves

plant vigor.

Keywords: Candida aff. ralunensis, Candida sake, Candida oleophila, Lachancea

nothofagi, Funneliformis mosseae, Water efficiency, Plant growth promotion

Resumen

La integración de microorganismos

beneficiosos en los sistemas agrícolas puede mejorar la resistencia de los

cultivos al estrés y aumentar el rendimiento. Se estudió la producción de

tomate (Solanum lycopersicum) en un ensayo experimental en invernadero,

durante una temporada completa de producción. El diseño experimental incluyó

tres factores: condición de riego (normal/bajo), adición del hongo micorrícico

arbuscular Funneliformis mosseae (con/sin), e inoculación con cuatro

levaduras nativas del suelo (Candida aff. ralunensis; Candida sake;

Lachancea nothofagi y Candida oleophila). No hubo efecto de la

co-inoculación de F. mosseae y las levaduras en las plantas de tomate.

La adición de F. mosseae aumentó la colonización micorrícica y las

variables de producción independientemente del nivel de riego; sin embargo, los

efectos sobre el crecimiento fueron variables. Ninguna de las levaduras

inoculadas aumentó la colonización micorrícica. La inoculación de C. aff. ralunensis y C. oleophila aumentó el diámetro del

tallo en todas las condiciones estudiadas. La inoculación de C. aff. ralunensis aumentó la relación fruto/flor en condiciones

normales de riego. La inoculación con C. sake aumentó la relación

fruto/flor en condiciones de riego bajo. La inoculación de micorrizas

arbusculares se presenta como una estrategia de producción beneficiosa para

aumentar la tolerancia de las plantas y mejorar el uso del agua. Proponemos

que la inoculación de C. aff. ralunensis y C.

oleophila mejora el vigor de la planta.

Palabras clave: Candida aff. ralunensis, Candida sake, Candida oleophila, Lachancea

nothofagi, Funneliformis mosseae, eficiencia del uso del agua, promoción del crecimiento vegetal

Originales: Recepción: 15/05/2023 - Aceptación: 22/11/2023

Introduction

Drought represents a

massive threat to agricultural productivity (24, 35),

affecting more than 64% of the world’s land. Almost 70% of Argentina is

occupied by drylands, including the extensive Patagonian region that suffers

strong desertification processes (48, 55).

During drought, osmotic stress suppresses overall plant growth (39, 43); accelerates the senescence of older

leaves (16); reduces the number, size and

viability of seeds; and delays germination (9),

flowering and fruiting (49, 56). Climate

change is likely to intensify these factors, further impairing normal growth

and reducing plant water use efficiency (12).

Crop water use efficiency is therefore a topic worthy of attention (45).

Rhizospheric

microorganisms that promote plant growth help plants become established in

their environment (32) by enhancing water

and nutrient acquisition (34, 51),

improving homeostasis and tolerance processes (3)

and alleviating abiotic stress (21),

among other possible mechanisms. One of the most studied fungi types in this

regard are mycorrhizal fungi and, more recently, yeasts have also been

considered. Mycorrhizal fungi are essential for the development of most plants

(52): this symbiosis improves plant establishment,

enhances plant nutrient uptake (5) and

protects host plants from the detrimental effects of osmotic stress caused by

water deficit (40). Inoculation with

arbuscular mycorrhizae (AM) is a common practice in agriculture and forestry (17). Furthermore, it is known that AM fungi

influence and are influenced by the activities of other soil microorganisms (2, 5). Microorganisms that facilitate the

development and function of mycorrhizal symbiosis are considered mycorrhizal

helper microorganisms (1, 5). Yeasts have

been shown to have growth-promoting properties in plants, including pathogen

control (11), phytohormone production (33, 47), phosphate solubilization (20), siderophore production (10) and increased AM root colonization (42).

The

use of AM fungi and other growth-promoting microorganisms can improve plant

establishment and help them cope with stress from factors such as drought and

nutrient limitations (6). Native

microorganisms have the advantage of being adapted and resistant to local

environmental stressors, so could be the most effective when inoculated in

plants cultivated in their own environments (37).

Inoculation with these microorganisms increases their number in the soil, thus

helping maximize their beneficial properties by promoting crop yield (11) and crop tolerance to environmental stress (26).

Microbial communities

present complex interactions between species, making it difficult to predict

their responses to changes in land use, especially in a context of global

change. Major research efforts are underway to generate strategies to combat

abiotic stress in plants, and although some are promising, such as farm

management practices using breeding and genetic engineering (54), they are time-consuming and expensive. The

use of microorganisms for multiple purposes may be an eco-friendly, sustainable

and cost-effective approach. Studying the interaction between microorganisms

and their relationship with plants in an environment with low water

availability could help us find low-cost, environmentally friendly

biotechnological tools. In Andean Patagonia, several studies have described

native rhizospheric yeast communities (27, 28)

and their physiological characteristics that promote in-vitro (29, 31) and in-vivo (32) plant growth. Tomato was selected as the

object of study here because of its agronomic significance and its role as a

model plant in scientific research (14).

The objective of the present work was to study how inoculation with arbuscular

mycorrhizae and plant growth-promoting yeasts adapted to local conditions can

influence tomato production in water-deficit conditions.

Materials

and methods

Experimental

design

We designed a

tri-factorial pot trial with two irrigation regimes (normal and low), two

mycorrhiza levels (with or without addition) and five yeast levels (with one of

4 yeast species or without yeast). The trial comprised 20 treatments with six

replicates each (120 plants).

Microbial

inocula

The arbuscular

mycorrhizal fungus used in our experimental trial was Funneliformis mosseae (F.M.;

ex Glommus mosseae). Soil inoculum containing 110 sporocarps per 10 g of

soil was produced under greenhouse conditions from trap plants at Estación

Experimental del Zaidín, CSIC (Spain).

The yeast strains

used belong to the Yeast Collection of the Centro Regional Universitario

Bariloche, Universidad Nacional del Comahue, Argentina. They were isolated from

rhizosphere soils of native forests in the Northwest region of Patagonia,

Argentina, and identified by Mestre et al. (2011, 2014). Yeast strains were selected based on their plant

growth-promoting traits (29, 31) and

osmotic tolerance. The four yeasts, Candida aff. ralunensis

(C.R.), Candida sake (C.S.), Lachancea nothofagi (L.N.) and Candida

oleophila (C.O.), produced auxin-like compounds and tolerated up to 10%

NaCl. In addition, C.R. L.S. and L.N. solubilized phosphates, and L.N. and

C.O. produced siderophores. The yeast strains were cultivated at 20 °C for 72

h on solid medium (MYP, g 100mL -1:

Malt extract 0.70, Yeast extract 0.05, Soybean peptone 0.23, Agar 1.50). Each

yeast strain was suspended in peptone water (1% Soybean peptone) to a turbidity

of 0.3 at 600 nm, equivalent to a suspension of 106

cells mL -1.

These cell suspensions were used to inoculate the seedlings. The timing and

final concentration of the inoculations are detailed in the section “Production

Conditions”.

Production

conditions

Commercial tomato

seeds (Solanum lycopersicum var. platense) were used. The seeds were

pre-treated by immersion in 20% sodium hypochlorite for 2 min, followed by

triple washing with sterile water, to reduce their microbial load. Three

hundred seeds were placed in a culture chamber under controlled conditions (16

hours of light at 25°C, 8 hours of darkness at 22°C) for 4 days, and 140

germinated seeds were then planted in alveolar trays with sterile commercial

seedling substrate (with an organic amendment). The Funneliformis mosseae (FM)

mycorrhizal inoculum was added to the substrate of half the trays in a 2 % P/V

ratio: plants in these trays were thus considered to be inoculated with

arbuscular mycorrhiza (F.M.+). The seedlings were incubated in a chamber under

controlled conditions (10 hours darkness at 20°C, 14 hours light at 28°C) and

periodically watered with sterile water. When the first true leaves appeared

(10 to 15 days after germination), 6 ml of yeast inoculum was applied to the

stem base of the seedlings as follows: 18 seedlings of each mycorrhizal

treatment were inoculated with a single yeast strain (C.R., C.S., L.N. or

C.O.), and 18 were inoculated with peptone water without yeast

(control, Y-). After 45 days in the germination chamber, all seedlings were

transferred to a greenhouse. The greenhouse belongs to the Forestry Department

of the Province of Rio Negro and is located in the city of Bariloche, Río

Negro, Argentina. Twelve seedlings per treatment were transplanted into pots

according to the following criteria: minimum height of 10 cm, at least 3 true

leaves, complete root system and well-adhered substrate when detached from the

tray insert. Each seedling was placed manually into a 7L pot containing a

mixture of perlite, peat and soil in a ratio of 1:1:2. The soil used in the

study, sourced from the vicinity of the greenhouse, is commonly employed for

cultivating horticultural and forestry seedlings in the area. Typical

production conditions were therefore replicated, using soil with its native

microbial community. Once in the greenhouse, 60 plants were kept under normal

irrigation conditions (W+) for the entire trial. For the remaining 60 plants

(W-) irrigation was discontinued 30 days after transplanting, and a pulse of

water (lasting 7 days) was applied only when visible symptoms of plant wilting

appeared (loss of stem and leaf turgidity). Normal and low irrigation regimes

were set up using a drip irrigation system, and the pots were distributed

randomly within each irrigation regime. The low irrigation treatment provided

only 15% of the amount of water provided in the normal irrigation treatment.

All the plants were

fertilized with commercial Nitrofull (Emerger) three times during the trial, at

different phenological stages of the plants: the first was 0.36 g per plant

when the plants had no fruit; the second and third doses were 0.8 g per plant,

one at the beginning of the fruit production period and the last one close to

the end of production. Weed control was carried out every 15 days and axillary

buds were eliminated to simulate productive conditions. The trial was designed

such that the production cycle would be completed during the Patagonian growing

season, from September (late winter) to April (early autumn), a total of 205

days.

Mycorrhizal

colonization: At the end of the production cycle, the root systems of 3 plants

from each of the 20 treatments were collected at random. They were first

carefully rinsed with tap water and then a portion (2 g per plant) was

conserved in alcohol 70% V/V and stained using the modified method of Phillips

and Hayman (38). The mycorrhizal status

of each plant was determined in fine roots (<2 mm diameter) using an optical

microscope (Olympus BX40). The presence of arbuscules was used as a diagnostic

feature of AM presence. For quantification, ten stained root fragments of 1cm

length were placed on a slide and observed with 200x magnification, in

triplicate, resulting in the observation of at least 300 fields per plant

(about 100 fields per preparation). Percentage of AM colonization (AM%) was estimated

using the method described by Giovannetti and Mosse (1980).

Growth variables: At

the end of the trial all plants were harvested. Plant and root length were

recorded with a tape measure (0.1 cm) and stem diameter with a digital caliper

(0.01 mm). Aerial and root material was harvested separately, dried at 90 °C to

constant weight and then weighed to determine dry biomass to the nearest 0.001

g.

Production variables:

Ripe tomatoes were harvested periodically throughout the trial. At the end of

the trial all fruits were harvested. The number of flowers and fruits per plant

was recorded. The fruit-to-flower ratio (FFR) was calculated as the ratio of

the number of fruits to the final number of flowers. Yield was determined by

calculating average fresh weight of fruit per treatment.

Statistical

analysis

To

determine whether the treatments affected the development of the tomato plants,

we carried out a three-way ANOVA test, taking into account the following

variables: percentage of arbuscular mycorrhiza colonization, root length, stem

diameter, dry shoot biomass, dry root biomass, number of flowers, number of

fruits, fruit to flower ratio and yield. Data were transformed when necessary

to achieve normality: AM% data were transformed with the square root of

arcsine, and FFR value and fruit number with the square root. A gamma distribution

was assumed for dry root biomass results. The figures present non-transformed

data. Tukey’s post-hoc tests were used to form homogeneous groups when

necessary (α = 0.05).

Results

None of the variables

analyzed in this trial showed significant interaction between the three factors

(3-way interaction), and no interaction was found between yeast inoculation and

the addition of AM (co-inoculation) for the variables analyzed.

Mycorrhizal

colonization

Neither the yeast

treatments nor the interactions had a significant effect on AM%, whereas F.M.

addition and irrigation conditions showed significant main effects. The AM% in

plants subjected to normal irrigation conditions was significantly higher than

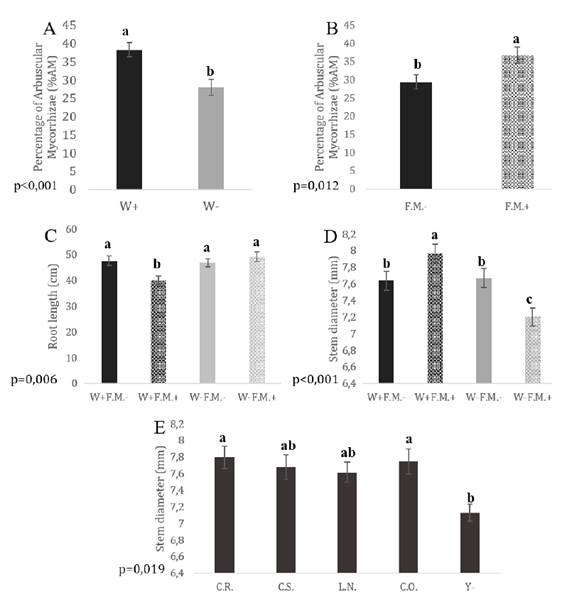

in plants under low irrigation conditions (W+ > W-; p = 0.001; figure

1A); AM% was significantly higher in plants with F.M. than in those without

it (F.M.- < F.M+; p = 0.012; figure 1B).

W+: normal irrigation; W-: low irrigation; F.M.-: without Funneliformis

mosseae.; F.M.+: with F. mosseae. C.R.: Candida aff. ralunensis; C.S.: C. sake; L.N.: Lachancea

nothofagi; C.O.: C. oleophila; Y-: non yeast inoculation. Mean

values and standard errors are given for each treatment (bars). Statistically

significant differences are indicated by different letters (Tukey’s post-hoc

test. p ≤ 0.05).

W+: riego normal; W-: bajo riego; F.M.- :

sin Funneliformis mosseae.; F.M.+: con F. mosseae. C.R.: Candida

aff. ralunensis; C.S.: C. sake; L.N.: Lachancea

nothofagi; C.O.: C. oleophila; Y-: sin inoculación de levadura. Se

indican los valores medios y los errores estándar para cada tratamiento

(barras). Las diferencias estadísticamente significativas se indican con letras

distintas (prueba post hoc de Tukey. p ≤ 0,05)

Figure 1. Effect of irrigation

(A) and mycorrhizal inoculation (B) on the percentage of mycorrhizal

colonization. Interacting effects of irrigation and mycorrhizal inoculation on

root length (C) and stem diameter (D). Effect of yeast inoculation on the stem

diameter (E) of tomato plants.

Figura 1. Efecto

del riego (A) y la inoculación micorrícica (B) sobre el porcentaje de

colonización micorrícica. Efectos interactivos del riego y la inoculación micorrícica

sobre la longitud radical (C) y el diámetro del tallo (D). Efecto de la

inoculación con levaduras sobre el crecimiento del diámetro del tallo (E) de

plantas de tomate.

Growth

variables

Root

length was not affected by the individual main factors but was significantly

affected by the interaction between irrigation condition and F.M. addition (p =

0.006). Roots were shorter in tomato plants subjected to normal irrigation

conditions with F.M. than in any other treatment (W+F.M.+ < W+F.M.-, W-F.M.+,

W-F.M.-; figure 1C).

Stem diameter was

affected by yeast inoculation as a main effect (p = 0.019): tomato plants

inoculated with C.R. or C.O. showed larger stem diameters than plants without

yeast inoculation (C.R. = C.O. > Y-; figure 1E, page 145).

Stem diameter was also affected significantly by the interaction between

irrigation condition and F.M. addition (p ≤ 0.001): the highest value was

obtained with F.M. and normal irrigation, intermediate values were observed for

both irrigation treatments without F.M., and the lowest values were obtained

with F.M. and low irrigation (figure 1D, page 145).

In the case of dry

shoot biomass, F.M. addition was the only factor that generated significant

differences (p = 0.015): plants without F.M. showed higher values than those

with FM (F.M- > F.M.+). The only factor that generated significant

differences for dry root biomass was the irrigation condition (p ≤ 0.001):

plants under low irrigation conditions had higher root dry biomass than those

receiving normal irrigation (W- > W+).

Production

variables

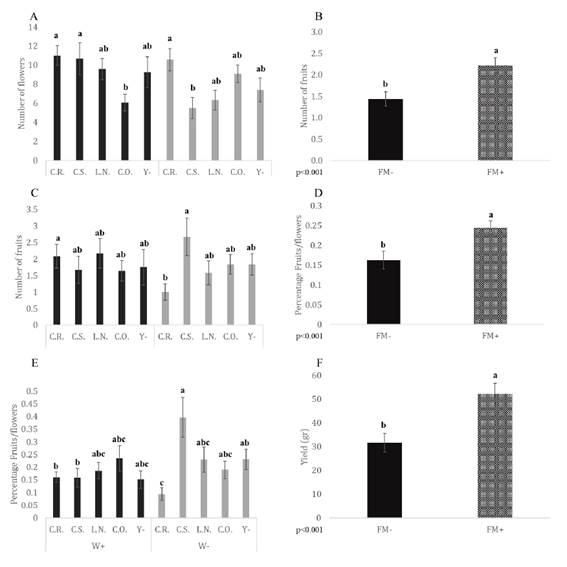

Flower numbers showed

a significant interaction between irrigation and yeast inoculation (p =

0.012). The number of flowers was higher in plants exposed to normal irrigation

conditions and inoculated with C.S. than in plants under low irrigation

conditions inoculated with the same yeast strain (W+C.S. > W-C.S.; figure 2A, page 147). On the other hand, of the normally

irrigated plants those inoculated with C.R. and C.S. showed higher numbers of

flowers than those inoculated with C.O. Of the plants with reduced irrigation,

those inoculated with C.R. had higher numbers of flowers than those inoculated

with C.S. The main effect of F.M. addition showed significant differences in

the number of fruits (p < 0.001): plants with F.M. produced 55% more fruit

than those without it (F.M.- < F.M.+; figure 2B, page

147). The number of fruits also showed a significant interaction between the

irrigation and yeast factors (p = 0.025). Plants inoculated with C.R. had

a higher number of fruits under normal irrigation than under low irrigation

(W+C.R. > W-C.R.; figure 2C, page 147), and plants

inoculated with C.S. had a higher number of fruits than plants inoculated with

C.R. under low irrigation conditions (W-C.S. > W-C.R.; figure

2C, page 147).

W+: normal irrigation; W-: low irrigation; F.M.-: without Funneliformis

mosseae.; F.M.+: with F. mosseae. C.R.: Candida aff. ralunensis; C.S.: C. sake; L.N.: Lachancea

nothofagi; C.O.: C. oleophila; Y-: without yeast inoculation. Mean

values and standard errors are given for each treatment (bars). Statistically

significant differences are indicated by different letters (Tukey’s post-hoc

test. p ≤ 0.05).

W+: riego normal; W-:

bajo riego; F.M.- : sin Funneliformis mosseae.;

F.M.+: con F. mosseae. C.R.: Candida aff. ralunensis;

C.S.: C. sake; L.N.: Lachancea nothofagi; C.O.: C. oleophila;

Y-: sin inoculación con levaduras. Se indican los valores medios y los errores

estándar para cada tratamiento (barras). Las diferencias estadísticamente significativas

se indican con letras distintas (prueba post hoc de Tukey. p ≤ 0,05)

Figure 2. Interactive effects

of irrigation and yeast inoculation on A) Number of flowers C) Number of fruits

and E) Fruits/flowers ratio. Effect of mycorrhizal inoculation on B) Number of

fruits D) Ratio fruits/flowers F) Yield.

Figura 2. Efectos

interactivos del riego y la inoculación de levadura sobre A) Número de flores

C) Número de frutos y E) Proporción frutos/flores. Efecto de la inoculación

micorrícica sobre B) Número de frutos D) Proporción frutos/flores F)

Rendimiento.

Funneliformis mosseae

addition

showed significant differences as a main effect for the fruit-to-flower ratio

(p < 0.001), which was higher in plants with F.M. than in those without it

(F.M.- < F.M.+; figure 2D, page 147).

The FFR also showed

significant interaction between irrigation and yeast inoculation (p = 0.005).

For plants inoculated with C.R., the FFR was significantly higher under

normal than low irrigation conditions (W+C.R. > W-C.R.; figure

2E, page 147). In contrast, for plants inoculated with C.S. the FFR was

lower in plants under normal irrigation conditions than low (W-C.S. >

W+C.S.). Plants under low irrigation conditions and inoculated with C.S. rendered

the highest FFR.

Yield showed significant

differences for F.M. addition as a main effect (p < 0.001): plants with F.M.

showed a 65% higher yield than plants without F.M. (F.M.- < F.M.+; figure 2F, page 147).

Discussion

Our results indicate

no three-way interaction between factors for any of the variables measured.

Statistical significance was observed for single main effects of the factors or

pairwise interactions, one of the interacting factors being the irrigation

condition. The irrigation regime therefore seems to be the main source of

variation for most of the variables analysed. Plants subjected to a low

irrigation regime received 85% less water and showed symptoms of osmotic

stress, such as a decrease in stem diameter and number of flowers. This may be

related to growth inhibition due to osmotic stress. Hydric stress decreases

stem and leaf growth and accelerates senescence and abscission in older leaves

(16). Under water deficit conditions,

plants generate strategies to modulate their soil water uptake capacity, such

as lateral root development or main root elongation (9,

22, 44); this explains the increase in root length and root dry

biomass observed under low irrigation conditions.

The effect of drought on mycorrhizal symbiosis was poorly

established since we found negative, positive and even neutral effects (4, 15, 25, 57). Drought effects on the establishment

and colonization of mycorrhizal fungi depend on several conditions, such as

plant and fungal species, environmental conditions and stress levels (4). In our work, limiting irrigation negatively

affected mycorrhizal colonization.

Other studies have

reported that co-inoculation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and yeasts can

have positive effects on plant growth and development (57). These effects may be related to beneficial

interactions between the AM fungi and yeasts, such as nutrient solubilization

and improved plant resistance to stress. In our study, however, co-inoculation

had no significant effect on tomato plants. This could be due to the particular

yeast and AM species used, soil conditions or production conditions.

Mycorrhizal colonization was observed in all the plants studied,

demonstrating that mycorrhizal communities in Patagonian soils are capable of

colonizing agriculturally important plants such as the tomato. Addition of F.

mosseae increased mycorrhizal colonization, which may be attributed to

higher inoculum pressure, the highest infectivity of F. mosseae, or a

beneficial synergistic effect of both AM communities on these annual plants.

The addition of F. mosseae increased productive parameters such as fruit

number, FFR and yield in tomato plants. Arbuscular mycorrhiza hyphae can

penetrate soil pores and extend beyond the root zone, increasing the soil

volume to be explored and the possibility of better nutrient uptake (41, 46). Additionally, AM fungi are known to

influence the nutrient balance of plants, including carbohydrate balance (7) and hormone production (50), two factors that affect flowering and fruit

set (8). This indicates that increased AM

colonization, in this case, the addition of F. mosseae, can positively

influence productive parameters, both under normal irrigation conditions and in

situations of water shortage.

The relationship

between Patagonian yeasts and native mycorrhizal colonization has been reported

in studies such as Mestre et al. (2017),

where a tendency of increased colonization of native mycorrhizae was observed

in poplars inoculated with the native yeast Tausonia pullulans. Fracchia et al. (2003)

recorded an increase in mycorrhizal colonization in soybean (Glycine max)

and red clover roots after double inoculation of F. mosseae and Rhodotorula

mucilaginosa, when the yeast was inoculated before F. mosseae. Our

results show that yeast inoculation did not significantly affect the percentage

of AM colonization; however, there was a tendency of increased mycorrhizal

colonization in plants inoculated with C. sake, without F. mosseae, under

both irrigation conditions. This suggests a possible mycorrhizal helper effect

of C. sake on native mycorrhizal fungi present in Patagonian soils.

Further study should be carried out on this relationship, considering factors

such as the concentration of each microorganism, the location, timing and

frequency of inoculations, the order of inoculation of the microorganisms, and

a combination of these factors, to enhance understanding and enable

improvements to be made in agricultural production strategies.

Enhancing the ability of native mycorrhizal fungi to colonize

economically important crops could be an alternative to using external

mycorrhizal inoculum, which has to be purchased by producers and adds to

production costs. From an environmental point of view, using native yeasts to

improve native mycorrhizal colonization may be advantageous in that the

introduction of foreign microorganisms can be avoided. Inoculation with C.

aff ralunensis and C. oleophila led to significantly larger stem

diameters than in plants without yeast, under both irrigation conditions and F.

mosseae addition. Plants with larger stem diameters are less susceptible to

environmental stress after transplanting (53).

Stem diameter is a general measure of plant resistance to drought (19), and is often correlated with transplant

vigor (23). The greater the vigor of the

plants, the more resilient they will be in adverse conditions and the more

capable of producing a large quantity of fruit. Therefore, inoculation of

either of these two yeasts can enhance overall plant resistance by increasing

plant vigor. Inoculation with C. aff ralunensis and C. oleophila are

proposed as a complement to inoculation with F. mosseae, as a way of

improving plant performance under water deficit conditions, in which the

results of F. mosseae addition were not as good as under normal

irrigation. We believe that one possible mechanism by which C. aff. ralunensis and C. sake promoted plant

productivity is linked to their ability to solubilize inorganic phosphate.

Argentine Patagonia has Andisol soils characterized by high phosphorus

retention (36); the presence of

solubilizing microorganisms is, therefore, crucial as they make this nutrient

available for plant uptake, improving plant nutrition. The direct

characteristics of C. sake as a plant growth promoter have been reported

in the work of Gollner et al. (2006),

where inoculation with C. sake increases the biomass of maize (Zea

mays) plants. Although in our research C. sake does not present

statistically significant differences compared to control plants, we observed

that under water deficit conditions it reached the highest values in productive

parameters such as fruit number and FFR. This suggests a promising trend,

although not statistically significant, indicating possible potential as a

growth promoter under water stress. Continuing research to explore this trend

is required to confirm its viability as a beneficial solution under water

scarcity conditions.

Conclusions

Our findings reveal that adding F. mosseae significantly

increases arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization and improves several productive

parameters in tomato plants, both under normal and limited irrigation

conditions. The use of indigenous rhizospheric yeasts such as C. aff. ralunensis and C. oleophila, is proposed for the

cultivation of more robust plants, not only in conventional irrigation systems

but also in situations of water scarcity. These findings indicate that

employing indigenous microorganisms could be a promising alternative to

external inoculants, potentially reducing production costs and obviating the

need to introduce foreign microorganisms into the environment. Arbuscular

mycorrhizae and yeast inoculation could be effective in improving crop yields

and increasing plant resistance to water stress. Nevertheless, additional

research is necessary to further understand these processes and optimize their

practical application in agriculture.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. A. Carron, Lic. D. Moguilevsky, Lic. V.

Bella, Prof. J. Puga, Tec. S. Olarte and Tec. N. Robredo for their helpful

assistance with technical and greenhouse work, and Audrey Urquhart BSc (Hon)

for language revision. We thank the authorities of Administración de Parques Nacionales

(Argentina) and Delegación de Bosques de Rio Negro for their courtesy and

cooperation. Lic. Boenel M was supported by a doctoral fellowship from the

Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET).

1.

Alonso, L. M.; Kleiner, D.; Ortega, E. 2008. Spores of the mycorrhizal fungus Glomus

mosseae host yeasts that solubilize phosphate and accumulate

polyphosphates. Mycorrhiza. 18(4):197- 204. DOI: 10.1007/s00572-008-0172-7

2.

Andrade, G.; Mihara, K. L.; Linderman, R. G.; Bethlenfalvay, G. J. 1997.

Bacteria from rhizosphere and hyphosphere soils of different

arbuscular-mycorrhizal fungi. Plant and Soil. 192: 71-79. DOI: 10.1023/A:1004249629643

3.

Armada, R. E.; Barea, J. M; Castillo P.; Roldán, A. 2015. Characterization and

management of autochthonous bacterial strains from semiarid soils of Spain and

their interactions with fermented agrowastes to improve drought tolerance in

native shrub species. Applied Soil Ecology. 96: 306-318. DOI: 10. 1016/j.

apsoil. 2015. 08. 008

4.

Augé, R. M.; Toler, H. D.; Saxton, A. M. 2015. Arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis

alters stomatal conductance of host plants more under drought than under amply

watered conditions: a meta-analysis. Mycorrhiza. 25: 13-24. DOI:

10.1007/s00572-014-0585-4

5.

Barea, J. M.; Azcón, R.; Azcón-Aguilar C. 2002. Mycorrhizosphere interactions

to improve plant fitness and soil quality. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 81:

343-351. DOI: 10.1023/A:1020588701325

6.

Bashan, Y.; de-Bashan, L. E.; Prabhu, S. R.; Hernandez, J. P. 2014. Advances in

plant growth-promoting bacterial inoculant technology: formulations and

practical perspectives (1998-2013). Plant and Soil .

378(1): 1-33. DOI: 10.1007/s11104-013-1956-x

7.

Boldt, K.; Pörs, Y.; Haupt, B.; Bitterlich, M.; Kühn, C.; Grimm, B.; Franken,

P. 2011. Photochemical processes, carbon assimilation and RNA accumulation of

sucrose transporter genes in tomato arbuscular mycorrhiza. Journal of Plant

Physiology. 168(11): 1256-1263. DOI: 10.1016/j.jplph.2011.01.026

8.

Bona, E.; Todeschini, V.; Cantamessa, S.; Cesaro, P.; Copetta, A.; Lingua, G.;

Gamalero, E.; Berta, G.; Massa, N. 2018. Combined bacterial and mycorrhizal

inocula improve tomato quality at reduced fertilization. Scientia Horticulturae

234: 160-165. DOI: 10.1016/j.scienta.2018.02.026

9.

Brunner, I.; Herzog, C.; Dawes, M. A.; Arend, M.; Sperisen, C. 2015. How tree

roots respond to drought. Frontiers in Plant Science. 6:547. DOI:

10.3389/fpls.2015.00547

10.

Calvente, V.; Benuzzi, D.; Tosetti, M. I. S. 1999. Antagonistic action of

siderophores from Rhodotorul aglutinis upon the postharvest pathogen Penicillium

expansum. International Biodeterioration and Biodegradation. 43: 167-172.

DOI: 10.1016/S0964-8305(99)00046-3

11.

El-Tarabily, K. A.; Sivasithamparam K. 2006. Potential of yeasts as biocontrol

agents of soil-borne fungal plant pathogens and as plant growth promoters.

Mycoscience. 47: 25-35. DOI: 10.1007/s10267-005-0268-2

12.

Farooq, M.; Hussain, M.; Wahid, A.; Siddique, K. H. M. 2012. Drought stress in

plants: an overview. In: Aroca R, editor. Plant responses to drought stress.

Berlin: Springer. 1-33. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-32653-0

13.

Fracchia, S.; Godeas, A.; Scervino, J. M.; Sampedro, I. J.; Ocampo, A.; Garcıa-Romera,

I. 2003. Interaction between the soil yeast Rhodotorula mucilaginosa and

the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi Glomus mosseae and Gigaspora rosea.

Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 35(5): 701-707. DOI:

10.1016/S0038-0717(03)00086-5

14.

Funes-Pinter, I.; Salomón, M. V.; Martín, J. N.; Uliarte, N.; Hidalgo, A. 2022.

Effect of bioslurries on tomato Solanum lycopersicum L and lettuce Lactuca

sativa development. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias.

Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 54(2): 48-60. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.082

15.

García, I. V. 2021. Lotus tenuis and Schedonorus arundinaceus co-culture

exposed to defoliation and water stress. Revista de la

Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias . Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina.

53(2): 100-108. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.044

16.

Gepstein, S.; Glick, B. R. 2013. Strategies to ameliorate abiotic stressinduced

plant senescence. Plant Molecular Biology. 82: 623-633. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-013-0038-z

17.

Gianinazzi, S.; Gollotte, A.; Binet, M. N.; van Tuinen, D.; Redecker, D.; Wipf,

D. 2010. Agroecology: the key role of arbuscular mycorrhizas in ecosystem

services. Mycorrhiza . 20(8): 519-530. DOI: 10.1007/s00572-010-0333-3

18.

Giovannetti, M.; Mosse, B. 1980. An evaluation of techniques for measuring

vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizal infection in roots. New phytologist. 489-500.

Retrieved August 17, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2432123

19.

Gollner, M. J.; Püschel, D.; Rydlová, J.; Vosátka, M. 2006. Effect of

inoculation with soil yeasts on mycorrhizal symbiosis of maize. Pedobiologia.

50 (4): 341-345. DOI: 10.1016/j. pedobi.2006.06.002

20.

Hesham, A. L.; Mohamed, H. 2011. Molecular genetic identification of yeast

strains isolated from Egyptian soils for solubilization of inorganic phosphates

and growth promotion of corn plants. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology.

21(1): 55-61. DOI: 10.4014/ jmb.1006.06045

21. Khan, N.; Bano, A.; Ali, S.; Babar,

M. 2020. Crosstalk amongst phytohormones from planta and PGPR under biotic and

abiotic stresses. Plant Growth Regulation. 90 (2): 189-203. DOI:

10.1007/s10725-020-00571-

22.

Koevoets, I. T.; Venema, J. H.; Elzenga, J. T. M.; Testerink, C. 2016. Roots

withstanding their environment: exploiting root system architecture responses

to abiotic stress to improve crop tolerance. Frontiers in plant science. 7:

1335. DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01335

23.

Kokalis-Burelle, N.; Vavrina, C. S.; Rosskopf, E. N.; Shelby, R. A. 2002. Field

evaluation of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria amended transplant mixes and

soil solarization for tomato and pepper production in Florida. Plant

and Soil . 238: 257-266. DOI: 10.1023/A:10144

64716 261

24.

Lobell, D. B.; Roberts, M. J.; Schlenker, W.; Braun, N.; Little, B. B.;

Rejesus, R. M.; Hammer, G. L. 2014. Greater Sensitivity to Drought Accompanies

Maize Yield Increase in the U.S. Midwest. Science 344 (6183): 516-519. DOI:

10.1126/science.1251423

25.

López-Ráez, J. A. 2016. How drought and salinity affect arbuscular mycorrhizal

symbiosis and strigolactone biosynthesis? Planta. 243(6): 1375-1385. DOI:10.1007/s00425-015-2435-9

26.

Marulanda, A.; Porcel, R.; Barea, J. M.; Azcón, R. 2007. Drought tolerance and

antioxidant activities in lavender plants colonized by native drought-tolerant

or drought-sensitive Glomus species. Microbial Ecology. 54: 543. DOI:

10.1007/s00248-007-9237-y

27.

Mestre, M. C.; Rosa, C. A.; Safar, S. V.; Libkind, D.; Fontenla, S. B. 2011.

Yeast communities associated with the bulk-soil, rhizosphere and

ectomycorrhizosphere of a Nothofagus pumilio forest in northwestern

Patagonia, Argentina. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 78(3): 531-541. DOI:

10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01183.x

28.

Mestre, M. C.; Fontenla, S.; Rosa, C. A. 2014. Ecology of cultivable yeasts in

pristine forests in northern Patagonia (Argentina) influenced by different

environmental factors. Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 60(6): 371-382. DOI:

10.1139/cjm-2013-0897

29.

Mestre, M. C.; Fontenla, S.; Bruzone, M. C.; Fernández, N. V.; Dames, J. 2016.

Detection of plant growth enhancing features in psychrotolerant yeasts from

Patagonia (Argentina). Journal of Basic Microbiology. 56(10): 1098-1106. DOI:

10.1002/jobm.201500728

30.

Mestre, M. C.; Pastorino, M. J.; Aparicio, A. G.; Fontenla, S. B. 2017. Natives

helping foreigners?: The effect of inoculation of poplar with patagonian

beneficial microorganisms. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition. 17(4):

1028-1039. DOI: 10.4067/S0718-95162017000400014

31.

Mestre, M. C.; Severino, M. E.; Fontenla, S. 2020. Evaluation and selection of

culture media for the detection of auxin-like compounds and phosphate solubilization

on soil yeasts. Revista Argentina de Microbiología. 53(1): 78-83. DOI:

10.1002/jobm.201500728

32.

Morrissey, J. P.; Dow, J. M.; Mark, G. L.; O’Gara, F. 2004. Are microbes at the

root of a solution to world food production? Rational exploitation of

interactions between microbes and plants can help to transform agriculture.

EMBO Reports. 5: 922-926. DOI: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400263

33.

Nassar, A. H.; El-Tarabily, K. A.; Sivasithamparam, K. 2005. Promotion of plant

growth by an auxin-producing isolate of the yeast Williopsis saturnus endophytic

in maize (Zea mays L.) roots. Biology and Fertility of Soils. 42:

97-108. DOI: 10.1007/s00374-005-0008-y

34.

Ngumbi, E.; Kloepper. J. 2016. Bacterial-mediated drought tolerance: current

and future prospects. Applied Soil Ecology . 105:

109-125. DOI: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2016.04.009

35.

Panda, D.; Mishra, S. S.; Behera, P. K. 2021. Drought tolerance in rice: focus

on recent mechanisms and approaches. Rice Science. 28(2): 119-132. DOI:

10.1016/j.rsci.2021.01.002

36.

Pereyra, F. X.; Bouza, P. 2019. Soils from the Patagonian region. In: Rubio G,

Lavado R, Pereyra F. (eds) The Soils of Argentina. World Soils Book Series.

Springer, Cham. 101-121. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-76853-3_7

37.

Pérez-Rodriguez, M. M.; Piccoli, P.; Anzuay, M. S.; Baraldi, R.; Neri, L.;

Taurian, T.; Lobato Ureche, M. A.; Segura, D. M. & Cohen, A. C. 2020.

Native bacteria isolated from roots and rhizosphere of Solanum lycopersicum L.

increase tomato seedling growth under a reduced fertilization regime.

Scientific Reports. 10(1): 1-14. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-72507-4

38.

Phillips, J. M.; Hayman, D. S. 1970. Improved procedures for clearing roots and

staining parasitic and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for rapid

assessment of infection. Transactions of the British Mycological Society. 55:

158-161.

39.

Roelfsema, M. R.; Hedrich, R. 2005. In the light of stomatal opening: new

insights into ‘the Watergate’. New Phytologist. 167: 665-91. DOI:

10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01460.x

40.

Ruiz-Lozano, J. M.; Aroca, R. 2010. Host response to osmotic stresses: Stomatal

behaviour and water use efficiency of arbuscular mycorrhizal plants. In: Koltai

H, Kapulnik Y (eds) Arbuscular Mycorrhizas: Physiology and Function. Springer,

Dordrecht. DOI: 10.1007/978- 90-481- 9489-6_11

41.

Sampaio de Almeida, D.; Mendonça Freitas, M. S.; Cordeiro de Carvalho, A. J.;

Beltrame, R. A.; Ola Moreira, S.; Vieira, M. E. 2021. Mycorrhizal fungi and

phosphate fertilization in the production of Euterpe edulis seedlings. Revista

de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias . Universidad Nacional de Cuyo.

Mendoza. Argentina. 53(2): 109-118. DOI: https://doi. org/10.48162/rev.39.045

42.

Sampedro, I.; Aranda, E.; Scervino, J. M.; Fracchia, S.; García-Romera, I.;

Ocampo, J. A.; Godeas, A. 2004. Improvement by soil yeasts of arbuscular

mycorrhizal symbiosis of soybean (Glycine max) colonized by Glomus

mosseae. Mycorrhiza . 14(4): 229-234. DOI: 10.1007/

s00572-003-0285-y

43.

Schroeder, J. I.; Kwak, J. M.; Allen, G. J. 2001. Guard cell abscisic acid

signalling and engineering drought hardiness in plants. Nature. 410:

327-30. DOI: 10.1038/35066500

44. Sharp, R. E. 2002. Interaction with

ethylene: changing views on the role of abscisic acid in root and shoot growth

responses to water stress. Plant, Cell & Environment. 25: 211-222.

DOI:10.1046/j.1365-3040.2002.00798.x

45.

Sivamani, E.; Bahieldin, A.; Wraith, J. M.; Al-Niemi, T.; Dyer, W. E.; Ho, T.

H. D.; Qu, R. 2000. Improved biomass productivity and water use efficiency

under water deficit conditions in transgenic wheat constitutively expressing

the barley HVA1 gene. Plant Sciences. 155(1): 1-9. DOI:

10.1016/S0168-9452(99)00247-2

46.

Smith, S. E.; Read, D. 2008. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. Academic Press. Great

Britain.

47.

Streletskii, R. A.; Kachalkin, A. V.; Glushakova, A. M.; Yurkov, A. M.; Demin,

V. V. 2019. Yeasts producing zeatin. Peer. J. 7: 6474. DOI: 10.7717/peerj.6474

48.

Tadey, M. 2006. Grazing without grasses: Effects of introduced livestock on

plant community composition in an arid environment in northern Patagonia.

Applied Vegetation Science. 9: 109-116. DOI:10.1111/j.1654-109X.2006.tb00660.x

49.

Tadey, M. 2020. Reshaping phenology: Livestock has stronger effects than

climate on flowering and fruiting phenology in desert plants. Perspectives in

Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics. 42: 125501. DOI:

10.1016/j.ppees.2019.125501

50.

Torelli, A.; Trotta, A.; Acerbi, L.; Arcidiacono, G.; Berta, G.; Branca, C.

2000. IAA and ZR content in leek (Allium porrum L.), as influenced by P

nutrition and arbuscular mycorrhizae, in relation to plant development. Plant

and Soil . 226: 29-35. DOI: 10.1023/A:1026430019738

51.

Turner, T. R.; James, E. K.; Poole, P. S. 2013. The plant microbiome. Genome

Biology. 14: 209. DOI: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-6-209

52.

Van Der Heijden, M. G.; Horton, T. R. 2009. Socialism in soil? The importance

of mycorrhizal fungal networks for facilitation in natural ecosystems. Journal

of Ecology. 97(6): 1139-1150. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01570.x

53.

Vavrina, C. S. 1996. An introduction to the production of containerized

vegetable transplants. Univ. FL., Cooperative Extension Service, Bulletin Nª.

302.

54.

Venkateswarlu, B.; Shanker, A. K. 2009. Climate change and agriculture:

Adaptation and mitigation strategies. Indian Journal of Agronomy. 54(2):

226-230.

55.

Voigt-Beier, E.; Fernandes, F.; Poleto, C. 2016. Desertification increased in

Argentinian Patagonia: anthropogenic interferences. Acta Scientiarum: Human

& Social Sciences, 38(1). DOI: 10.4025/actascihumansoc.v38i1.30177

56.

Xu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Jia, B.; Zhou, G. 2016. Elevated-CO2 response

of stomata and its dependence on environmental factors. Frontiers in Plant

Science. 7: 657. DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00657

57. Zhu, X. C.; Song,

F. B.; Liu, S. Q.; Liu, T. D.; Zhou, X. 2012. Arbuscular mycorrhizae improves

photosynthesis and water status of Zea mays L. under drought stress. Plant and Soil Environ. 58: 186-191.

Funding

This work was

supported by the “Universidad Nacional del Comahue-Centro Regional

Universitario Bariloche” under Grant 04-B200; “Fondo para la Investigación

Científica y Tecnológica (FONCYT)” under Grant PICT 2018-3441 and “Consejo Nacional

de Ciencia y Técnica” under Grant PIP 0235.

The authors report

there are no competing interests to declare.

Availability of data

and material

All data generated or

analyzed during this study have been included in this published article.

Data availability: Accession numbers for nucleotide sequences of Candida

aff ralunensis CRUB 1774, Candida sake CRUB 1997, Lachancea

nothofagi CRUB 2011 and Candida oleophila CRUB 2104 are KU693289,

KF826535, KF826536 and MZ191065, respectively.