Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 55(2). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2023.

Original article

Hazard

indicators in urban trees. Case studies on Platanus x hispanica Mill. ex Münchh and Morus alba L. in Mendoza city-Argentina

Indicadores

de riesgo en el arbolado urbano. Casos de estudio en Platanus hispanica y

Morus alba en la ciudad de Mendoza-Argentina

Ana Paula

Coelho-Duarte 2

1

Centro Científico Tecnológico CCT CONICET Mendoza. Instituto de Ambiente, Hábitat

y Energía. Av. Ruiz Leal s/n Parque Gral. San Martín. CP 5500. Mendoza. Argentina.

2

Universidad de la República. Facultad de Agronomía. Departamento Forestal. Av. Garzón

780. Sayago. CP 12900. Montevideo. Uruguay

*

cmartinez@mendoza-conicet.gob.ar

Abstract

Urban forests

significantly benefit cities and people´s wellbeing. However, under suboptimal

growth conditions, they can pose risks. The tree risk and tree hazard

assessments in public spaces bring together several protocols for preventing

damage to people and property. This article aims to strengthen the database on

forest resources at the urban scale and to identify key characteristics of

relevant species of street trees in Mendoza-Argentina. In terms of methodology,

trees of Platanus hispanica (London Plane tree) and Morus alba (Mulberry

tree) were evaluated in situ by indicators related to the probability of

failure such as defects, injuries and stress signals. The results show

deterioration of part of the urban forest, as well as the greater resilience of

P. hispanica when compared to M. alba. We conclude that

systematically implementing these assessments will

provide guidelines for the sustainable management of urban trees, improving

forest infrastructure under sustainable development guidelines.

Keywords: Platanus hispánica,

Morus alba, risk

assessment, urban forest, urban tree management

Resumen

Los bosques

urbanos aportan numerosos beneficios a las ciudades y a la calidad de vida de

sus habitantes. No obstante, pueden ofrecer riesgos cuando su crecimiento no es

óptimo. La evaluación de riesgo o peligrosidad de árboles en el espacio público

reúne una serie de protocolos para prevenir daños a personas y bienes

materiales. Este articulo busca fortalecer la base de

información del recurso forestal a escala urbana e identificar características particulares

de especies relevantes del arbolado público de Mendoza-Argentina. En términos

metodológicos, se evalúan in situ una muestra representativa de ejemplares de Platanus

hispanica y Morus alba con defectos, lesiones y signos de estrés.

Los resultados muestran el grado de deterioro de parte del universo forestal

urbano, como también la resiliencia de P. hispanica sobre M. alba.

Se concluye que la aplicación de estas evaluaciones en forma sistemática y

planificada, aportará directrices para el manejo sustentable del arbolado

urbano; que mejore la infraestructura del bosque bajo lineamientos de

desarrollo sustentable.

Palabras clave: Platanus hispánica, Morus alba,

evaluación de riesgo, bosque urbano, manejo del arbolado urbano

Originales: Recepción: 31/05/2023 - Aceptación: 04/12/2023

Introduction

Trees growing in

cities are conditioned by certain variables compromising their performance.

In this case,

Mendoza-Argentina, with approximately 700,000 street trees only in the

metropolitan area, has gained national and international recognition as an

“oasis city.” However, Mendoza has an arid climate and restrictive growth

resources-mainly drought and thermal stress- (14).

These circumstances require efficient management and monitoring in order to

ensure this natural resource and the numerous ecosystem services provided.

The most

frequently used species in urban alignments, particularly in the city of

Mendoza, are Platanus hispanica (9%), Morus alba (39%), y Fraxinus

excelsior L and Fraxinus americana. (20%), accounting for 68% of total street

trees (15, 17). Platanus hispanica (London

Plane trees) and Morus alba (Mulberry trees) are species widely used in

the city of Mendoza, both for their size, of 1st and 2nd

magnitude respectively, and for their shade and ecosystem services of

regulation and comfort. In this context, urban trees provide numerous benefits,

improving the urban climate, mitigating “heat island” intensity effects in

climates with high heliophany; hydrating the atmosphere and reducing summer

heat loads with consequent energy savings (22);

allowing the retention of suspended particles and noise mitigation by foliage;

increasing comfort conditions in public spaces and significantly contributing

to urban aesthetics (15). According to

dendrochronological analyses carried out in situ (13), the studied specimens show an approximate

age of between 90 years (Mulberry trees) and 119 years (London Plane trees),

while also showing symptoms of water and thermal stress and some obvious hazard

indicators, such as cracks, hollows, and exudates.

Risk assessment

of trees growing in urban public spaces (2, 4)

supports subsequent improvement of tree growing conditions, enhancing benefits

and preventing damage to people, material losses or service outages. Among

several methods for risk assessment of urban trees, those using visual

assessment and best known in urban arboriculture are the “Tree Hazard

Evaluation Method” (16), “A Guide to

Identifying, Assessing, and Managing Hazard Trees in Developed Recreational

Sites of the Northern Rocky Mountains and the Intermountain West” (8), and “Best Management Practice - Tree Risk

Assessment” (6). In this work, we applied

the rapid visual evaluation protocol (1, 3).

Our objectives

are to strengthen the database and the analysis of urban forest in terms of

risk assessment identifying key characteristics of important species in the

city while providing guidelines for sustainable management of urban trees.

The hypothesis

stated that “Growth patterns of urban trees reflect changes occurring in the

city, such as frequent and severe pruning, impermeabilization of irrigation

ditches, construction of infrastructure and land development. These stress

factors, together with water scarcity and rising temperatures, impact growing

conditions and increase tree failure likelihood. Platanus hispanica is

comparatively more resilient to these impacts than Morus alba”.

Materials

and Methods

Study

area

The province of

Mendoza, situated at the foot of the Andes Mountains, is in central-western

Argentina and included in the South American arid diagonal, between 32° and

37°35’ south latitude - 66°30’ and 70°35’ west longitude (figure

1).

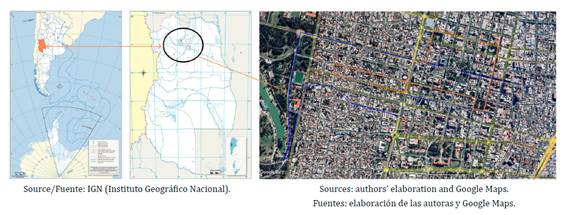

Figure 1. Location

of the study area and map of the assessment route. Yellow and blue lines

indicate walking tours.

Figura 1. Ubicación

del área de estudio y mapa de la ruta de evaluación. Líneas naranja y azul

indican los recorridos realizados.

Mendoza city is

characterized by sustained aridity, a temperate-dry climate (BWk-Koppen),

restricted water resources (average rainfall 250mm/year) and high constant

solar radiation throughout the year (1840 MJ/m2). The annual potential

evapotranspiration (ET) is 782mm, indicating a water deficit of 532mm. The

Mendoza Metropolitan Area (MMA) is an urban conglomerate with more than two

million inhabitants characterized by massive presence of trees in an urban

structure -tree/inhabitant ratio = 0.50 in 2021; (19);

i.e., one tree every two inhabitants.

The urbanized

area has a high percentage of green spaces and tree alignments parallel to

urban blocks and road layouts. An artificial irrigation network made up of

irrigation canals carry water from the mountain snowmelt (14) supporting this forestation. However, the

sustained scarcity of water resources during the decade 2010-2020 and the

progressive loss of irrigation efficiency compromised growth, structural

stability and forest health.

Tree

Assessment

The two most

frequent species were surveyed following a circuit that passed through the

areas of low building density (< 2m2/m3) to the

densely built-up area (>2 to 4 m2/m3). In the surveyed

area, around 840 tree individuals were observed in street alignments, at

regular planting intervals. Data collection was carried out between 22nd

and 24th March 2023, in the area located between Colón Street (to

the south), Emilio Civit/Sarmiento Street (to the north), San Martín Street (to

the east) and Boulogne Sur Mer Street (to the west) (figure 1).

For risk

assessment, walking tours were conducted along sidewalks and streets, according

to a level 1 assessment (6), based on the

rapid assessment method according to Coelho Duarte (2021b).

This method aims to identify obvious tree defects and hazardous situations,

without determining a final risk level.

The assessments

resulted in a profile of probable failures per species and biomechanical

adaptations. For this, the risk management of urban trees guide by Pokorny (2003) was used. Chapter 3, How to detect

and assess hazardous defects in trees, describes tree defects divided into

seven categories.

Results

and Discussion

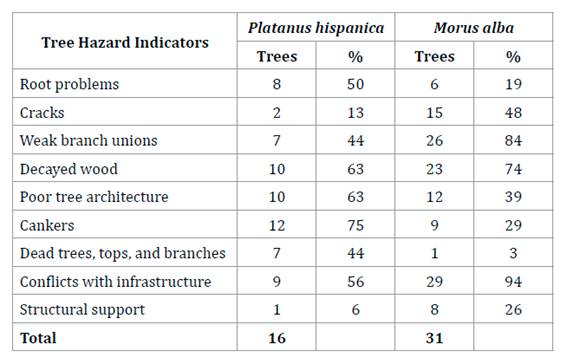

A total of 47

trees with hazardous defects were detected, 16 London Plane and 31 Mulberry

trees, representing 6.5% of assessed trees. This low percentage of trees with

higher likelihood of failure is expected and consistent with Coelho-Duarte (2021a), who recommends three different

levels of assessment to optimize risk management.

Tree

Hazard Indicators

Table 1, shows

tree hazard indicators identifying defective trees by species.

Table 1. Number

of trees for each hazard indicator and occurrence (%) by species.

Tabla 1. Número

de árboles para cada indicador de riesgo y ocurrencia por especie (%).

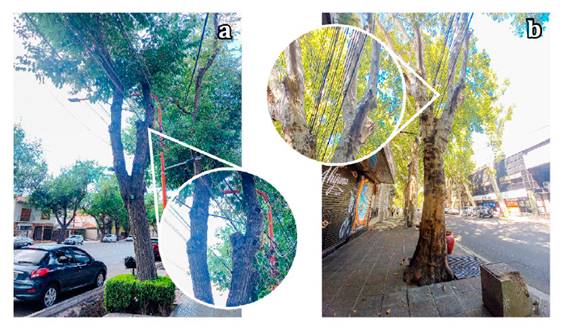

Decayed

Wood

Decayed wood

results from the interaction among the tree, biodeterioration agents (such as

bacteria, fungi or xylophagous insects) and environmental conditions (such as

humidity and temperature) (7). In living

trees, as decay progresses, cavities and hollows may appear, reducing

structural strength and stability of the individuals (2). Rotten wood, the presence of fungal fruiting

bodies, cavities, hollows, cracks, wood bulging and bark oozing are indicators

of advanced wood decay (16, 20, 28).

In 63% of London

Plane trees and 74% of Mulberry trees, some type of decay was observed during

the assessment circuit, most of it due to severe or inadequate pruning, in

which the trees are not able to complete wound compartmentalization (figure 2, page 156).

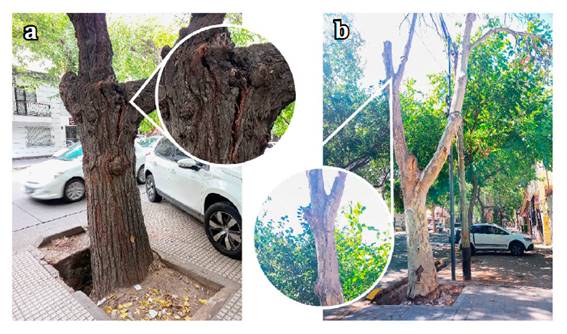

Figure 2. Decay

defect observed on a- Morus alba on Peatonal Sarmiento and b- Platanus

hispanica with dry branches on Montevideo Street.

Figure 2. Defecto

de pudrición observados en a- Morus alba de la Peatonal

Sarmieneto y b- Platanus hispanica con ramas secas, en calle

Montevideo.

Cavities with

rotten wood were observed in trunks, while branch advanced decay with large

pruning cuts showed, in some cases, wound wood and in others, loss of wood and

cavities. No fungal fruiting bodies were observed during data collection,

probably caused by the study taking part during late summer-autumn, with high

temperatures.

In some trees,

decay was associated with longitudinal cracks, especially in trees with

codominant stems and included bark and cankers. Defects simultaneously

occurring, and potentiated can increase failure likelihood, like cracks

separating codominant stems with deterioration in the union area (8, 20). This combination of problems was mainly

observed in Mulberry trees, associated with crown shape and consecutive

pruning.

Among tree

defence strategies against biodeterioration agents, the process of heartwood

formation consists of wood gaining natural durability thanks to biochemical changes

(7, 11). Another important defence

mechanism of trees is compartmentalization, first described by Shigo (1977) who stated four tree barriers formed in

the Compartmentalization of Decay in Trees (CODIT) model, with changes

at the chemical and anatomical level, preventing microorganisms from advancing

into the wood. More recently, the letter D for Decay is also used as Damage,

as compartmentalization can occur after a wound, with prior tissue infection (12).

In London Plane

trees, wound wood formation was observed, even when pruning cuts or wounds

caused by vehicular traffic, were large (figure 2).

Cracks

A crack is a

separation in the wood tissue (16), and

one major defect in more severe cases as they indicate the tree is already

failing (20). Cracks can be formed when a

trunk or branch does not support a certain load, either due to poorly closed

wounds, split of weak unions or branches with overloaded limbs (2). They can also be caused by frost damage or sunscald

(28). Vertical cracks following the

direction of longitudinal fibers, were present in 48% of Mulberry trees,

combined with the presence of codominant V-shaped stems and decay (figure

3a, page 157).

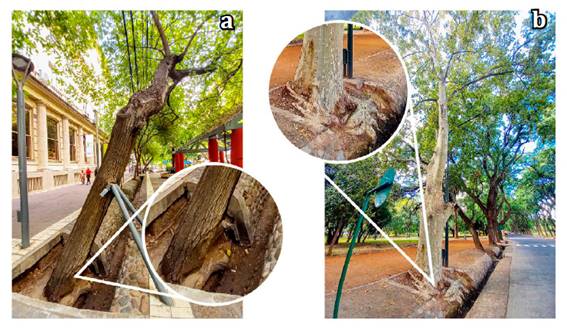

Figure 3. Crack

defect in a- Morus alba and b- Platanus hispanica.

Figura 3. Defecto

de grietas en a- Morus alba y b- Platanus hispanica.

In London Plane

trees, they were rarely observed (13%), mostly associated with dead wood (figure 3b, page 157). These defects have a high to imminent likelihood

of failure, and treatment should be recommended.

Root

problems

Site factors

such as reduced space for root development, shallow, compacted, or poor soil,

cause tree decline in urban areas (27).

Limited space for root growth of these first magnitude species, such as London

Plane trees, and second magnitude like Mulberry trees, is compounded by

impermeabilized irrigation ditches of Mendoza. Although this does not normally

result in direct tree damage, decreasing soil moisture and oxygen availability,

reduces tree ability to recover from injury, insect attack and/or disease (5). Also, root weakness results in loss of

anchorage and support (28), increasing

the possibility of whole-tree overturning. Thus, significant changes in the

critical root radius (CRR) can lead to a high failure potential especially when

more than 40% of the roots within this zone are damaged (9, 20). In Mulberry trees, impacts of ditch

impermeabilization were observed in 19% of the trees (figure 4a,

page 157).

Figure 4. Root

problems related to pot dimensions or planting site, and impermeabilization; a-

Morus alba; b- Platanus hispanica.

Figura 4. Problemas

del sistema radical relacionado con las dimensiones de la cazuela o sitio de

plantación, e impermeabilización; a- Morus alba; b- Platanus

hispánica.

In 50% of London

Plane trees some root problems were observed, such as girdling and exposed

roots in search of oxygen (figure 4b, page 157).

Girdling roots

compress root collar, hindering water, nutrients, and sap transport from and to

the roots (9, 10). These roots can

originate in the nursery itself, in seedlings grown in small pots, or when the

tree is grown in a small rigid space, where structural roots are unable to grow

laterally (16).

Weak

branch unions

Wood at the stem

union has anatomical changes that generate greater cohesion (25) to fulfil the function of absorbing and

transmitting wind loads until they dissipate into the soil (28). Epicormic shoots emerge from dormant

adventitious buds activated by stress conditions, such as topping (12). These buds may be present in the outer

growth layers, resulting in superficial attachment. The larger the epicormic

shoot, the greater the load on this weak union. On the other hand, included

bark may be generated during the development of bifurcated stems or branch

insertions which, instead of generating the more cohesive axillary wood, grow

with bark between the stems, resulting in no connection between them. This may

occur due to an intrinsic species trait, as in those with opposite buds, or

after inappropriate management, altering bud development (24). Included bark can be detected by the

V-shaped insertion, as opposed to a strong union, which would be U-shaped. Both

included bark -especially between codominant stems resulting in opposing loads

of similar magnitude- and epicormic shoots are types of weak unions present in

trees (20). Eighty-four percent of

Mulberry trees showed codominant, V-shaped structural branches with a very

small angle of insertion and branches overextended towards the roadside. In

some cases, this defect was combined with cracks, cankers, or rots (figure 5a).

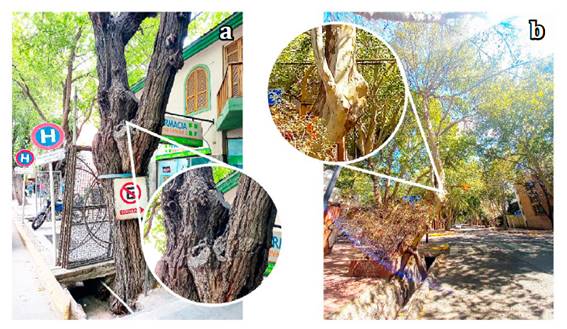

Figure 5. Defects

concerning weak branch unions or codominant stems; a- Morus alba;

b- Platanus hispanica.

Figura 5. Defectos

referidos a uniones débiles de ramas o troncos codominantes; a-Morus

alba; b- Platanus hispanica.

This makes stem

splits the main likelihood of failure. In London Plane trees, 44% had weak

unions, mainly in the most intensively managed trees, where the crown is

largely made up of epicormic shoots and, in some cases, these weak unions were

combined with decayed wood (figure 5b).

Cankers

Cankers are

areas with damaged cambium (16) on

trunks, branches, and roots (2). They can

be caused by fungi, insects, lightning or mechanical damage, such as wounds

caused by vehicles, lawn mowers, among others. According to Pokorny (2003), regardless of the origin of the damage,

more than 40% affectation of the circumference of a tree may cause failure and,

in turn, if the canker is associated with decay, it can quickly weaken the

tree. In the streets of Mendoza city, cankers were mainly associated with

pruning wounds and decay, being recorded in 29% of the Mulberry trees and 75%

of the London Plane trees. Figure 6a (page 159), shows a

Mulberry tree with abnormal basal growth, appearing as a “wood belt” (16), which may have been caused by damage during

changes in the sidewalk.

Figure 6. Canker

present in a- Morus and b- Platanus.

Figura 6. Defectos

compatibles con cancros en a- Morus y, b- Platanus.

In one specimen

of London Plane an abnormal discoloration, combined with branch dieback, may

have been associated with disease. In another case, a gall-like growth was

observed, with a significant change in bark texture (figure 6b,

page 159). According to Mattheck et al. (2015),

this form is not associated with a severe structural problem. The problem is

aggravated when the canker is associated with decayed wood.

Poor

tree architecture

Poor

architecture suggests imbalance and weakness of branches, trunk, or whole tree.

According to Pokorny (2003), indicators could be unbalanced

crown leaning, overextended, twisted, bent or harp-shaped branches, multiple

stems or epicormic shoots originating from the same area and stump sprouts.

Among the trees

assessed, 63% of the London Plane trees and 39% of the Mulberry trees showed

some problem related to architecture, especially observed in those subsequently

intervened by pruning, resulting in an unbalanced, curved shape (figure

7a) and with overextended branches towards the roadside.

Figure 7. a- Imbalance

in the morphology of a Mulberry tree in Peatonal Sarmiento. b- London

Plane tree with poor architecture accompanied by decayed wood.

Figura 7. a- Desequilibrio

en la morfología de Morus, en Peatonal Sarmiento. b- Platanus con

arquitectura pobre acompañada de madera seca.

Although these

indicators, according to Pokorny (2003), correspond

to a moderate likelihood of failure, these defects are in some cases combined

with the presence of decayed wood (figure 7b).

Dead

trees, tops, and branches

Dead branches

can remain attached to the tree for a long time, and suddenly break off as they

no longer have the tension that keeps them attached (20).

This was observed in 3% Mulberry trees, and 44% London Plane trees, especially

where impermeabilisation hindered water availability (figure 8).

Figure 8. London

Plane individuals showing signs of dieback.

Figura 8. Ejemplares

de plátanos con signos de “muerte regresiva”.

The dieback

observed in London Plane specimens may be associated with site factors leading

to root decay, such as soil compaction or impermeabilisation that impede root

gas exchange reducing root mass and, consequently, water and nutrient

absorption (16). As a result, the tree

starts to die out from the branch tips inwards (20).

Slenderness

(H:D)

Slender trees

may be more prone to mechanical failure, causing permanent bending or stem

breakage (8). The slenderness index,

characterizing likelihood of failure, is calculated by dividing tree total

height by the diameter at breast height (both in meters). Many authors classify

the likelihood of failure as possible for slenderness between 60 and 80,

probable between 81 and 100, and imminent over 100. When “lion tailing” pruning

is done, leaving branches accumulated at the ends of main stems, slenderness is

increased. Another factor increasing this index is tree planting near tall

buildings, reducing light availability, and promoting growth in height without

an increase in trunk diameter (15)

something the tree will correct only under healthy, vigorous conditions (28). Figure 9 (page 161), shows

this behavior in a London Plane specimen showing signs of crown lifting

pruning. In addition, the epicormic origins of these branches, with a weaker

union, as well as the presence of non-compartmentalized pruning wounds with

decay, can increase likelihood of failure.

Figure 9. Defect

in London Plane trees compatible with slender individuals.

Figura 9. Defecto

en Platanus compatible con ejemplares esbeltos.

Conflicts

with infrastructure

In addition to

the risk of structural failure, interference with pedestrian walkways,

underground utilities or utility poles and wires should be considered in the

risk assessment (6). The presence of

aerial utility wiring in the city of Mendoza with either Mulberry or London

Plane trees (figure 10, page 161), increases the need for

frequent interventions on the tree crown to reduce the occurrence of friction

between branches and wires.

Figure 10. Conflicts

with utility wiring and lighting poles; a- Morus alba; b- Platanus

hispanica.

Figura 10. Interferencias

con cableado y postes de iluminación pública; a- Morus alba; b-

Platanus hispanica.

These conflicts

were observed in 94% of the Mulberry trees and 56% of the London Plane trees. Greater

deterioration is observed in the Mulberry trees in general, compared to the

London Plane trees.

Biomechanical

adaptation

Biomechanics

study how trees adapt to different growth sites, climatic conditions, and

stresses (2). Ditches create special

conditions for root performance, and in many cases, impermeabilization adds

resistance making root growth limited. In some individuals of both species,

structural roots and root collar growth, was observed above ground level and

towards the roadside curb (figure 11, page 162).

Figure 11. Structural

roots and root collar growth above ground level.

Figura 11. Crecimiento

de las raíces estructurales y del cuello por arriba del nivel del suelo.

Although this

tissue contains dormant adventitious buds, that become active under

stress-generating epicormic shoots, it does not provide the expected structural

anchorage (16). In addition, the wood in

this area is exposed to mechanical damage and deterioration agents such as

fungi and xylophagous insects.

Structural

support

Supports are

necessary when the tree has a probable or imminent likelihood of failure due to

high pedestrian/vehicle occupancy rate or presence of targets that cannot be

moved (12). This generally occurs when

tree adaptation is slow compared to the response needed to reduce the hazard.

In the study area, supports were observed on Mulberry trees tying co-dominant

stems, where a crack separating them was already visible (figure

5a, page 158). Supports were also observed on steeply inclined trees in

both species (figure 12).

Figure 12. Individuals

of Platanus and Morus with structural supports, orthopedics or

“crutches”.

Figura 12. Ejemplares

de Platanus y Morus con soportes estructurales, ortopedias o

“muletas”.

When using

supports, tree reactions such as wound generation or positive adaptive response

must be monitored, and the option of relocating, reinforcing, or removing the

support, should be evaluated. However, in some cases, supports generated wounds

or cracks, indicating it should have been removed after the tree corrected the

lean.

General

discussion

The failure

profile indicated that the main problems identified in London Planes were cankers

with decay, combined with poor branch architecture, caused by successive and intensive

pruning to release aerial wiring. These problems indicating a “probable”

likelihood of failure, were more evident in streets with ditch

impermeabilization and/or inefficient irrigation. In most streets, London Plane

trees were in good phytosanitary condition and the wounds were

compartmentalized.

On the other

hand, Mulberry trees showed more dangerous defects, with an “imminent” likelihood

of failure. Indicators were the presence of cracks in the codominant stems union

with bark included, or along overextended structural branches, in both cases

combined with decay. Mulberry trees were also intervened year after year, with

large cuts releasing utility wiring. In many cases, this resulted in an

imbalanced architecture of the crown, with branches overextending towards the

roadside. Additionally, pruning cuts were not effectively compartmentalised,

with evident decay, cankers, and exudations. In addition to interventions due

to competition with the aerial utilities, changes around the root system also

affected some individuals, such as changes in soil level and impermeabilization

of ditches, also observed in London Planes.

In addition to

the obvious conflict with the city’s grey infrastructure, these trees are ageing

without adequate maintenance. The literature indicates that large, mature trees

generate more ecosystemic services than small trees (18,

21, 26). The problem is established when these large individuals

deteriorate and with indicators of “probable to imminent” likelihood of

failure. This, combined with high occupancy rate of the area and the large size

of parts that can fail, results in high to extreme risk. In this scenario,

increasing decay and consequent reduction in vigor, in addition to the already

detected conditions of water and heat stress, seriously impact ecosystem

services and tree safety. This reinforces the need for the development of

short-term strategic management including the replacement of trees posing the

highest risks.

Conclusions

This rapid

visual assessment allowed for an efficient survey of street trees, identifying

main problems in two major species in Mendoza city -Platanus hispanica and

Morus alba and in areas with the highest occupancy rate, where the fall

of a whole or part of a tree could cause significant damage. Potential failure

or defect profiles increase efficiency in surveying monitoring zones, making

assessments more effective, especially in areas with higher vehicular and

pedestrian traffic flow.

In cases with a

probable to imminent likelihood of failure, we recommended following the risk

management protocol and making more in-depth assessments at a level 2 or basic

visual level, indicating risk mitigation treatments.

In comparative

terms, London plane showed the presence of cankers with decay, combined with poor

branch architecture, while mulberry trees showed more dangerous defects, and

“imminent” likelihood of failure, cracks in the union area of codominant

structural branches with bark included and signs of decay. In this sense,

London plane is recommended for new urban forests in highly consolidated areas

and under intense anthropic pressure, compared to Mulberry tree.

Although this

case study does not provide an in-depth assessment of species adaptation, the

defect profiles can be considered as a preliminary conclusion on London Plane

trees being more resilient to pruning interventions compared to Mulberry trees.

However, changes near the root zone, and in the frequency and amount of

irrigation, lead to a considerable decrease in vigor.

The planning and

integration of knowledge, scientific advances and practical experience have a

positive impact on the management and preservation of urban forests as a public

resource in cities. This is even more relevant in the case of Mendoza, given

climatic and geographical conditions in terms of water restriction,

environmental vulnerability, and advances in urbanization patterns.

Acknowledgements

The authors

would like to thank the Comisión Sectorial de Investigación Científica de la

Universidad de la República (CSIC/UDELAR), the Consejo Nacional de

Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) and the Agencia Nacional de

Promoción de la Ciencia y Tecnología (ANPCyT) for the funding received through

the project PICT 2018-03590 in support of the development of this research. And

express gratitude to Agustina Sergio for her friendly cooperation.

1. Ameneiros,

C.; Fratti, P.; Sergio, A.; Coelho-Duarte, A. P.; Ponce-Donoso, M.;

Vallejos-Barra, Ó. 2022. Comparison of visual risk assessment methods applied

in street trees of Montevideo city, Uruguay. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 54(2): 38-47. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.081

2. Calaza, P.;

Iglesias, I. 2016. El riesgo del arbolad o urbano. Contexto, concepto y

evolución. Mundi- Prensa. 526 p.

3. Coelho-Duarte

A. P. 2021a. Evaluación del riesgo de los árboles urbanos: propuesta de un

protocolo para Montevideo, Uruguay. Tesis de maestría. Universidad de la

República (Uruguay). Facultad de Agronomía. Unidad de Posgrados y Educación

Permanente

4. Coelho-Duarte

A. P.; Daniluk-Mosquera G.; Gravina V.; Vallejos Barra O.; Ponce-Donoso, M.

2021b. Tree risk assessment: Component analysis of six visual methods applied

in an urban park, Montevideo, Uruguay. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 59:

127005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127005

5. Czaja, M.;

Kołton, A.; Muras, P. 2020. The complex issue of urban trees-stress factor

accumulation and Ecological Service Possibilities. Forests. 11(9): 932.

https://doi.org/10.3390/f11090932

6. Dunster, J.

A.; Smiley, E. T.; Matheny, N.; Lilly, S. 2017. Tree risk assessment manual.

International Society of Arboriculture. 194 p.

7. Forest

Products Laboratory. 2010. Wood Handbook. Wood as an Engineering Material. USDA

Forest Service. General Technical Report FPL- GTR-190. 509 p.

https://doi.org/10.2737/FPLGTR-190

8. Guyon, J.;

Cleaver, C.; Jackson, M.; Saavedra, A.; Zambino, P. 2017. A guide to

identifying, assessing, and managing hazard trees in developed recreational

sites of the northern Rocky Mountains and the intermountain West. USDA Forest

Service. Northern and Intermountain Regions. Report number R1-17-31. 82 p.

https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/fseprd571021.pdf

9. Hauer, R. J.;

Johnson, G. R. 2021. Relationship of structural root depth on the formation of

stem encircling roots and stem girdling roots: Implications on tree condition.

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 60: 127031.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127031.

10. Johnson, G.;

Fallon, D. 2021. Stem girdling roots the underground epidemic killing our

trees. University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy. Urban Forestry. (11). 13 p.

https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/226077/Stem%20Girdling%20Roots-The%20Underground%20Epidemic%20Killing%20Our%20Trees.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

11. Kim, Y. S.;

Funada, R.; Singh, A. P. (Eds.). 2016. Secondary xylem biology: Origins,

functions, and applications. Elsevier/Academic Press.

12. Lilly, S.;

Bassett, C.; Komen, J.; Purcell, L. 2022. Arborists’ Certification Study Guide

(4th ed.). International Society of Arboriculture. 468 p.

13. Martinez, C.

F. 2014. Crecimiento bajo déficit hídrico de especies forestales urbanas de la

ciudad oasis de Mendoza, Argentina y su área metropolitana. Ecosistemas:

Revista Científica de Ecología y Medio Ambiente. Revista Ecosistemas 23(2):

147-152. Doi.: 10.7818/ECOS.2014.23-2.20

14. Martinez, C.

F.; Cavagnaro, J. B.; Roig, F. A.; Cantón, M. A. 2013. Respuesta al déficit

hídrico en el crecimiento de forestales del bosque urbano de Mendoza. Análisis

comparativo en árboles jóvenes. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias.

Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 45(2): 47-64.

15. Martinez, C.

F.; Cantón, M. A.; Roig Juñent, F. A. 2014. Incidencia del déficit hídrico en

el crecimiento de forestales de uso urbano en ciudades de zonas áridas. Caso de

Mendoza, Argentina. INTERCIENCIA Revista de Ciencia y Tecnología de América.

Venezuela. Vol. 39 (12): 890-897.

16. Mattheck,

C.; Bethge, K.; Weber, K. 2015. The body language of trees: Encyclopedia of

visual tree assessment. KS Druck GmbH. 548 p.

17.

Municipalidad de Capital. 2012. 1° Censo Georreferenciado del Arbolado Público

de la Ciudad de Mendoza. Municipalidad de la Ciudad de Mendoza. Inédito.

18. Nowak, D.;

Crane, D.; Stevens, J.; Hoehn, R.; Walton, J.; Bond, J. 2008. A Ground-Based

Method of Assessing Urban Forest Structure and Ecosystem Services.

Arboriculture & Urban Forestry. 34(6): 347-358. https://doi.org/10.48044/jauf.2008.048

19. INDEC 2022.

https://www.indec.gob.ar/indec/web/Nivel4-Tema-2-41-165. Fecha de consulta

22/05/2023.

20. Pokorny, J.

D. 2003. Urban tree risk management: A community guide to program design and

implementation. USDA Forest Service. Northeastern Area, State and Private

Forestry.

https://www.fs.usda.gov/naspf/publications/urban-tree-risk-managementcommunityguide-program-design-and-implementation.

NA-TP-03-03. 204 p. https://www.fs.usda.gov/nrs/pubs/na/NA-TP-03-03.pdf

21. Rötzer, T.;

Moser-Reischl, A.; Rahman, M. A.; Grote, R.; Pauleit, S.; Pretzsch, H. 2020.

Modelling urban tree growth and ecosystem services: Review and Perspectives. En

F. M. Cánovas, U. Lüttge, M. C. Risueño, & H. Pretzsch (Eds.). Springer

International Publishing. 82(405-464). https://doi.org/10.1007/124_2020_46

22. Ruiz, M. A.;

Colli, M. F.; Martinez, C. F.; Correa, E. 2022. Park cool island and

built environment. Ten years evaluation in Parque Central, Mendoza-Argentina.

Sustainable Cities and Society. Volume 79: 103681.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2022.103681

23. Shigo, A.

1977. Compartmentalization of decay in trees. USDA Forest Service. Agriculture

Information. 73. https://permanent.fdlp.gov/gpo65586/ne_aib405.pdf

24. Slater, D.

2018. Natural bracing in trees: Management recommendations. Arboricultural

Journal. 40(2): 106-133. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071375.2017.1415560

25. Slater, D.;

Harbinson, C. 2010. Towards a new model of branch attachment. Arboricultural

Journal. 33(2): 95-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071375.2010.9747599

26. Wang, Y.;

Bakker, F.; De Groot, R.; Wörtche, H. 2014. Effect of ecosystem services

provided by urban green infrastructure on indoor environment: A literature

review. Building and Environment. 77: 88-100.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2014.03.021

27. Watson, G.

W.; Hewitt, A. M.; Custic, M.; Lo, M. 2014. The management of tree root systems

in urban and suburban settings II: A review of strategies to mitigate human

impacts. Arboriculture and Urban Forestry. 40: 249-271.

https://doi.org/10.48044/jauf.2014.025

28. Wessolly,

L.; Erb, M. 2016. Manual of Tree Statics and Tree Inspection. Patzer Verlag.

288 p.