Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 56(1). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2024.

Original article

Morphostructural

composition and meat quality in local goat kids from the northeastern region of

Mexico

Composición

morfoestructural y calidad de la carne en cabritos locales de la región noreste

de México

Yuridia Bautista-Martínez1,

Lorenzo Danilo Granados-Rivera2,

Rafael Jimenez-Ocampo3,

1Universidad

Autónoma de Tamaulipas. Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia. 87000.

Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas. México.

2Instituto

Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agricolas y Pecuarias. Campo

Experimental General Terán. 67400. General Terán, Nuevo León. México.

3Instituto

Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias. Campo

Experimental Valle del Guadiana. 34170. Durango, Durango. México.

4Instituto

Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias. Campo

Experimental La Laguna. 27440. Matamoros. Coahuila. México.

*maldonadoj.jorge@hotmail.com

Abstract

Goat farming is

an important activity in northern Mexico. In this sense, “cabrito” or kid goat

is a typical regional dish with high economic and cultural value. However,

information on the morphostructural composition and meat quality of these local

specimens is scarce. Given this, the objective was to evaluate morphostructural

characteristics, carcass and meat quality in local kids according to sex in the

northeastern region of Mexico. For this purpose, 14 kids (7 males and 7

females) 57 days old were slaughtered. Morphostructural composition was

evaluated with 22 zoomometric and phenotypic variables. Carcass characteristics

were evaluated by considering different body structures, carcass yield and

degree of fatness. Meat quality was determined by physicochemical

characteristics, nutritional value and fatty acid profile. The sex effect was

evaluated by t-test of independent means and Chi-square. Meat physicochemical

characteristics, nutritional value and morphostructure of local kids were heterogeneous

and showed no differences (P≥0.05) concerning sex. Carcass, kidneys, head, neck,

rib and loin weights were higher in males than in females (P≤0.05). Fatty acids

(FA) found in greater proportion were palmitic (C16:0), oleic (C18:1, n-9),

stearic (C18:0), and myristic (C14:0). These FA comprised 80.85 % of the lipid

profile of male meat and 76.83% of females. These results are the basis for

future programs aimed to improve production systems. Differences found could

shed light on future efforts on how to differentiate goat meat from this region

of Mexico and enter new markets directly benefiting small producers.

Keywords: meat, carcass,

nutritional quality, fatty acid profile

Resumen

La

caprinocultura es una actividad muy importante en el norte de México por la

producción de leche y carne. En este sentido, el cabrito es un platillo típico

de esta región con valor económico y cultural elevado, no obstante, la

información que describe la composición morfoestructural y calidad de carne de

estos ejemplares locales, ha sido poco documentada. Debido a lo anterior, el

objetivo fue evaluar las características morfoestructurales, calidad de canal y

carne en cabritos locales de acuerdo con el sexo (machos y hembras) en la

región noreste de México, para esto se sacrificaron 14 cabritos (7 machos y 7

hembras) de 57 días de edad. Para evaluar la composición morfoestructural, se

consideraron 22 variables zoométricas y fenotípicas. Las características de la

canal se evaluaron considerando las distintas estructuras corporales,

rendimiento en canal y grado de engrasamiento. Se determinó calidad de carne

midiendo las características fisicoquímicas, valor nutricional y perfil de

ácidos grasos. Se evaluó el efecto del sexo mediante una prueba de t de medias

independientes y Chi cuadrada. La estructura morfoestructural de los cabritos

locales es heterogénea, y no mostraron diferencias (P≥0,05) respecto del sexo.

El peso de la canal, riñones, cabeza, cuello, costillar y lomo fueron mayores

en machos que en hembras (P≤0,05). Las características fisicoquímicas y valor

nutricional de la carne no mostraron diferencias entre sexos. Los ácidos grasos

(AG) que se encontraron en mayor proporción fueron; palmítico (C16:0), oleico

(C18:1, n-9), esteárico (C18:0), y mirístico (C14:0). Estos AG comprendieron el

80,85 % del perfil lipídico de la carne de los machos, mientras que en hembras

representaron el 76,83 %. Estos resultados son la base para futuros programas

de mejora del sistema productivo y donde las diferencias encontradas podrían

arrojar luz sobre esfuerzos futuros, sobre cómo diferenciar la carne de cabrito

en esta región de México e ingresar a nuevos mercados que beneficiarían

directamente a los pequeños productores.

Palabras clave: carne, canal,

calidad nutricional, perfil de ácidos grasos

Originales: Recepción: 26/06/2023 - Aceptación: 22/03/2024

Introduction

In Mexico, goat

production is focused on meat and milk. During 2022, carcass meat production

achieved 77,000 tons, and 160 million liters of milk (32). The

predominant production system is extensive, with animals known as “local”, with

an undefined phenotype derived from mating different breeds such as Alpina,

Saanen, Nubia, and Toggenburg (31). Besides

feeding suckling kids, the produced milk is used for cheese, cajeta (a milk candy-type),

and typical regional candies. Kids are slaughtered and consumed at

approximately 30 days old. Their meat is soft and tender, low-fat, pearly white

and juicy. As a traditional Mexican dish, particularly in the north of Mexico,

it is consumed on special events and can be cooked in various presentations

like “al pastor” (shawarma), fried, or roasted. It is also considered a gourmet

dish reaching high prices in restaurants (32).

Similar dishes

are prepared in other countries such as Spain, where this meat should meet

certain characteristics (9), India, China,

Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh, and Iran, where goat production is important (13). However, in

Mexico, particularly in the northeast, information on body structure, carcass

quality, and nutritional properties of kid meat is scarce. Nevertheless, breeds

such as Payoya, Gokcead, Maltese, Majorera, Blanca celtiberica, Negra serrana

and Moncaica, have been extensively documented (6).

In this context,

generating local information on kid meat produced in this region of Mexico is

important given that it supplies almost all the consumed kid meat in the

northern states of Mexico. Regional goat raising relies on the environmentally

best-adapted breeds. In this sense, particular production strategies can set

particular qualities, where denominations of origin can trigger added value (26). The

aforementioned is particularly important for smallscale, and highly social and

economically marginalized producers (31, 35). Therefore,

our objective was to evaluate morphostructural traits, carcass and meat

quality, and fatty acid profile considering sex in local kids from the

northeastern region of Mexico.

Material

and methods

Animal

management and study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the

Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia – Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas

in the pronouncement CBBA_01_2023.

Place

of study

This experiment

was conducted in a commercial production unit, located in ejido Ignacio

Zaragoza, Viesca, Coahuila, Mexico, within the region known as Comarca

Lagunera. The climate is desert, semi-warm with cool winters (BWhw), mean

annual rainfall of 240 mm, with average temperature of 25°C, ranging from -1°C

in winter to 44°C in summer.

Animals

and feeding

Before the

experiment, during the summer, a herd of 150 local empty goats mated naturally

during grazing and in housing pens.

Fourteen

57-day-old kids (7 males and 7 females) weighing 7.7 kg (live weight; LW) were

housed with their mothers from birth in individual 2 x 3 m pens provided with

shade, drinkers and ad libitum mineral salts.

Goat feeding was

based on grazing from 8:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m., and from 4:00 p.m. to 8:00 p.m.,

keeping the goats penned during the hottest hours of the day, and taking

advantage of this space of time for kid suckling. Table 1 shows plant

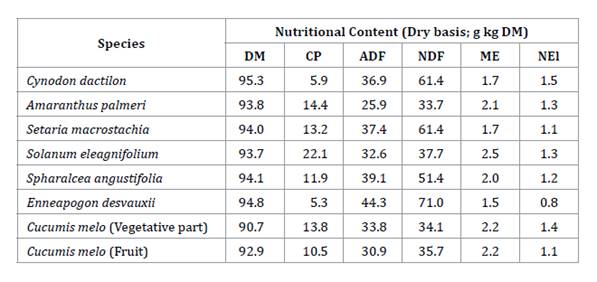

nutritional value during grazing.

Table

1. Average chemical composition of the

main plant species consumed by local goats in northeastern Mexico.

Tabla 1. Composición

química promedio de las principales especies de plantas consumidas por caprinos

locales en el noreste de México.

DM= dry matter; CP= crude protein; ADF= acid

detergent fiber; NDF= neutral detergent fiber; ME= metabolizable energy; NEl=

net energy for lactation.

DM= materia seca; CP= proteína cruda; ADF= fibra

detergente ácido; NDF= fibra detergente neutro; ME= energía metabolizable; NEl=

energía neta para la lactancia.

Transportation

and slaughtering of goat kids

Kids were

slaughtered at weaning (57 days of age). Twelve hours before slaughter, they

were separated from their mothers and transported to the Municipal

slaughterhouse in Matamoros, Coahuila, where they were slaughtered following

the Official Mexican Standard NOM-033-SAG/ZOO-2014.

Zoometric

and morphostructural measurements

Before

slaughter, zoometric traits were measured: live weight (LW), face width (FW),

skull length (SL), ear length (EL), ear width (EW), neck width (NW), neck

length (NL), height at withers (HW), chest circumference (CC), barrel

circumference (BC), flank depth (FD), lumbosacral height (ASL), leg length

(LL), cane perimeter (CP). Morphostructural traits recorded included skin

pigmentation (SP), hoof pigmentation (HP), mucous membrane pigmentation (MP),

presence of wattles, beard, and horns (1=present, 2=absent) (8,

12, 14).

Carcass

yield

Before

slaughter, the PV was recorded. Subsequently, carcass productive components

were sectioned and removed (head without skin, skin, legs, lungs and trachea,

liver, heart, rumen, intestine and testicles -in males-). Yield was calculated

by dividing cold carcass weight (24 hours postmortem at 4°C) by the initial

live weight, expressed as a percentage (4).

Nutritional

value

From each kid,

200 g of Longissimus dorsi muscle meat were grounded to homogenize and

determine protein, fat, collagen, and moisture content with a FoodScan™ Meat

Analyzer.

Physicochemical

characteristics of meat

To measure meat

physicochemical characteristics, the Longissimus Dorsi muscle was

removed with a transverse cut between the 12th and 14th

rib, 24 hours postmortem (4).

pH

The pH was

measured 24 h post mortem from a cut of the Longissimus dorsi muscle

at the 12th rib, inserting the electrode of a portable potentiometer

(HANNA® instruments, HI99163, Singapore), previously calibrated with pH 4.00

and 7.00 buffer solutions.

Color

Color was

measured at three different points on the surface of the Longissimus dorsi muscle

24 h post mortem, using the Hunter method. A colorimeter (Minolta, Mod

CR-400/410, Tokyo, Japan) determined L* (lightness), a* (red-green) and b*

(yellow-blue) (11).

Drip

loss

Drip loss was

determined after Wang et al. (2016) with

modifications. Approximately 30 g of the Longissimus dorsi muscle meat

sample were weighed and placed in Styrofoam cups hanging from a thread without

touching the walls of the cup. Subsequently, they were stored at 4°C and

weighed 24 h later. Drip loss was expressed as the percentage of weight loss to

initial weight (8).

Water

retention capacity (WRC)

The WRC was

analyzed following Guerrero et al. (2002), with

modifications. Five g of finely minced meat of the Longissimus dorsi muscle,

24 h postmortem, were weighed and homogenized with 8 ml of sodium

chloride for 1 minute using a glass rod. Subsequently, it was left to rest for

30 minutes in an ice bath. The extract was centrifuged for 25 minutes at 35,000

r.p.m. The supernatant was drained and the volume was measured in a graduated

cylinder. The amount of ml of solution retained in 100 g of meat was reported.

Cooking

yield

Cooking yield

was determined after Liu et al. (2012) with

modifications. From each meat sample, 50 g of the Longissimus dorsi muscle,

24 h postmortem were weighed using an analytical scale and placed in

Ziploc-type bags. They were then placed in a water bath at 90°C for 15 minutes.

Meat internal temperature was measured with a stem thermometer. Subsequently,

they were left to rest at room temperature for 30 minutes. After this time,

they were re-weighed. Cooking yield was obtained by considering initial vs. final weight differences, expressed as percentages.

Fatty

acid (FA) profile

Fat purification

was carried out through FA methylation. We proceeded to oven-dehydrate 30 g of

the Longissimus dorsi muscle at 60°C. Subsequently, meat samples were

purified (15) and methylated

according to Jenkins (2010) modified by Granados-Rivera

et al. (2017).

Once the FA methyl esters were obtained, they were determined in a Hewlett

Packard 6890 chromatograph with an automatic injector equipped with a silica

capillary column (100 m x 0.25 mm x 0.20 μm thickness, Sp-2560, Supelco). FA

identification was done by comparing retention times of each peak obtained from

the chromatogram against a standard of 37 FA methyl ester components, and a

specific standard for cis-9, trans-11 and trans-10, cis-12 isomers (Nu-Check).

Statistical

analysis

Significant

differences among quantitative zoometric traits, nutritional value, carcass and

meat quality, and fatty acid profile between male and female goat kids were

determined by a t-student test for independent means with the SAS version 9.3

program. Given morphostructural variables are frequencies, a Chi-square (χ²)

test was used to assess independence concerning sex.

Results

Zoometric,

morphostructural, and carcass measurements

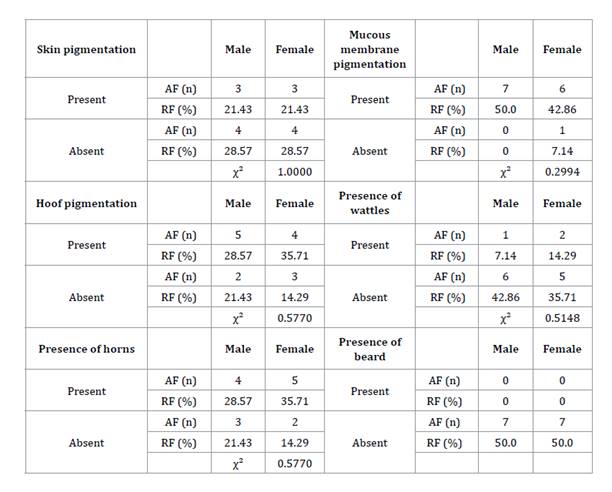

Morphostructure

of local kids was heterogeneous, and no differences (P≥0.05) were found between

sexes (table

2).

Table

2. Absolute (AF) and relative (RF)

frequencies for morphostructural traits in local goat kids.

Tabla 2. Frecuencias

absolutas (FA) y relativas (FR) para las características morfoestructurales en

cabritos locales.

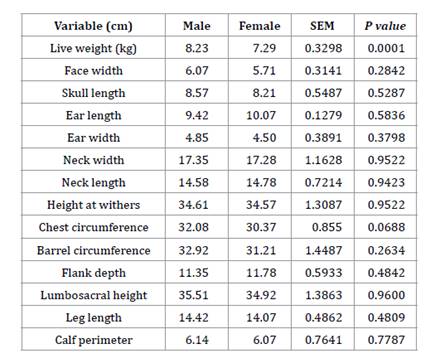

Concerning live

weight, males were significantly heavier compared to females at 57 days old,

with an average difference of 0.940 kg. Regarding other body traits, no

differences (P≥0.05) were found between sexes (table 3).

Table

3. Live weight and zoometric measurements

of local goat kids.

Tabla 3. Peso

vivo y medidas zoométricas de cabritos locales.

SEM: Mean standard error.

SEM: error estándar de la media.

Regarding yield

components and carcass traits, weights of cold carcass, kidneys, head, neck,

ribs, and loin were higher in males than females (P≤0.05), showing significant

differences between sexes. Other carcass components did not show differences

between sexes (table 4).

Table

4. Yield components of the carcass in

local goat kids.

Tabla 4. Componentes

de rendimiento de la canal en cabritos locales.

SEM: Mean standard error.

SEM: error estándar de la media.

Nutritional

value and meat physicochemical characteristics

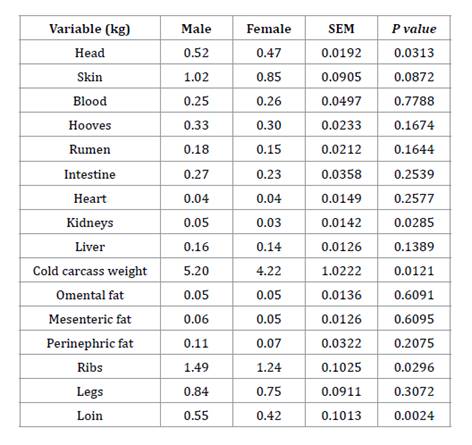

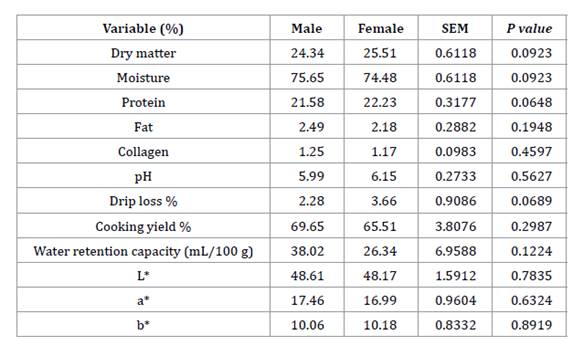

Meat nutritional

value of male and female kids showed no differences (P≥0.05) (table

5).

Table

5. Nutritional value and meat quality of

local goat kids.

Tabla 5. Valor

nutricional y calidad de la carne de cabritos locales.

L*: lightness index; a* red to green index; b*:

yellow to blue index; SEM: Mean standard error.

L*: índice de luminosidad; a*índice de rojo a verde;

b*: índice de amarillo a azul; SEM: error estándar de la media.

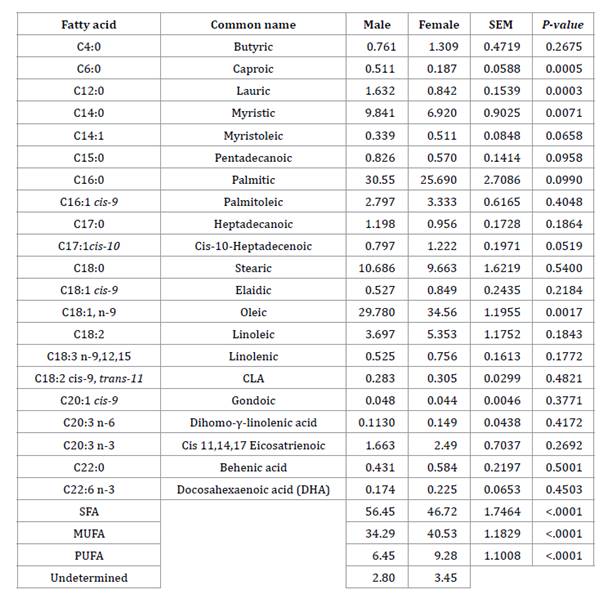

Fatty

acid profile

The FAs found in

greater quantity in meat were palmitic (C16:0), oleic (C18:1, n-9), stearic

(C18:0), and myristic (C14:0). These, in total, represented an average of

80.85% of the FA that make up male meat and 76.83% of female meat (table

6).

Table

6. Fatty acid profile (g/100 g-1

of fat) in local goat kids’ meat.

Tabla 6.

Perfil de ácidos grasos (g/100 g-1 de grasa) en carne de cabritos

locales.

ab

Different letters in the same row show statistical differences (P ≤ 0.05); SEM:

Mean standard error; SFA= saturated fatty acids, MUFA= monounsaturated fatty

acids; PUFA= polyunsaturated fatty acids.

ab

Letras diferentes en la misma fila presentan diferencias estadísticas (P ≤

0,05); SEM: error estándar de la media; SFA= ácidos grasos saturados, MUFA=

ácidos grasos monoinsaturados; PUFA= ácidos grasos poliinsaturados.

Meat

concentration of caproic, lauric, myristic, and oleic acids showed differences

(P≥0.05) regarding sex, being higher in male meat.

The

concentration of saturated FA was significantly higher in males compared to

females with values of 56.45% and 46.72%, respectively, while the amount of

monounsaturated (40.53 %) and polyunsaturated (9.28 %) FA was higher females

compared to males (P<0.05).

Discussion

Zoometric,

morphostructural and carcass measurements

Morphostructural

characteristics were heterogeneous, without defined traits in terms of sex. In

this regard, Maldonado-Jáquez et al. (2023) report that,

in local kids from northern Mexico, the dominant phenotype corresponds to

animals without wattles or beards. This coincides with our study since no

animal presented wattles (total frequency of 78.57%), or beard. Furthermore,

these same authors mention that local kids present pigmented mucous membranes

and horns. In this study, 85.71% of the animals presented pigmented mucous

membranes and 94.28% presented horns, reaffirming this information. These

results can be attributed to local animals of this region being a cross between

different breeds, with varying phenotypic traits.

On the other

hand, sex had a significant effect on animal weight, where males were heavier

than females. This same result is reported by Maldonado-Jáquez

et al. (2023)

for 30-day-old kids, where males weighed an average of 800 g more than females.

This effect is explained by goat growth curves (2), showing

shorter growth phases in males (ending up to 4 months before) than females.

Moreover, the growth hormone has a marked effect on the early development of males,

when the highest growth rates are observed between 20 and 60 days old (27,

29).

Regarding body

measurements, our results differ from the reported by Maldonado-Jáquez

et al. (2023),

who indicated differences in neck length and width, body length, chest

circumference, and leg length, probably given by age differences. While Maldonado-Jáquez

et al. (2023)

considered 1 to 30 days, our research measured at 57 days old. Age

significantly influences live weight and body conformation (3).

Cold carcass was

heavier in males than in females, as found by Todaro et al.

(2004)

who reported differences in carcass weight with respect to sex with values of

5.7 kg and 5.3 in males and females of the Nebrodi breed, respectively, at 47

days old. However, Bonvillani et al. (2010) indicated no

differences concerning sex, with average weights of 5.34 and 5.48 kg for

females and males respectively in local kids from Córdoba, Argentina, at 60 to

90 days old. This could be due to age heterogeneity rather than sex. However,

the breed effect could also influence carcass weight of males and females.

Differences in

rib and loin weights between males and females can be attributed to males

having a higher live weight at 56 days old, and consequently, a higher carcass

weight reflected in a higher weight in these structures. This sex difference

may assist decisions considering males being directed to the sale of cuts (30), for wholesale

sale and/or in restaurants, reaching high prices. This relies on the fact that

a single piece is equivalent to 50% of the price paid to the producer for a

whole live goat (5). Females not

meeting breeding characteristics can be commercialized as meat.

Nutritional

value of meat

Sex does not

influence meat nutritional value. Other authors concluded that in Nebrodi breed

kids, sex did not change the protein, fat, and ash contents of meat (34).

Protein content of local kid meat from northeastern Mexico is higher than the

20.79% and 19.72% reported by Horcada et

al. (2012),

as well as the 2.37% fat reported by Kawęcka et

al. (2022).

Fat percentage in kid meat is low compared to other species, probably because

of age, since fat formed in early stages is mesenteric, while intramuscular fat

is formed during adulthood (20).

Physicochemical

characteristics of meat

Sex does not

influence meat pH at 24 hours post mortem. Values found are close to those

reported in Payoya kids at 30 days old (19). However,

others report higher pH (23). Regardless,

our values are over the recommendations for normal meat considering species for

meat production (1). This effect could be

due to kids being only fed with milk and muscle glycogen before slaughter is

not abundant given goat restless behavior (20)

rather than chronic stress before slaughter, a condition that has been

documented to cause high pH values in meat (1).

Drip loss, water

retention capacity, cooking yield, and color were not modified by sex, as

already observed (33, 34). This may be

explained by absent differences in pH since low or high final pH will determine

the amount of water lost during handling, as well as pale or dark colors. The

lightness index and yellow index values obtained in this study are within the

reported ranks (10, 19, 34). Conversely,

the values obtained for the a* parameter are higher than other reports (33, 34), probably given by factors like breed and

age at the time of slaughter.

Fatty

acid profile

Fatty acids

found in greater quantity are within the reported ranges. Regardless of breed

or feeding systems, FAs are palmitic acid (C16:0) with minimum values from

17.32 g/100 g (34) to 25.0 g/100 g (20);

stearic acid (C18:0) with values from 7.87 g/100 g (21)

to 19.71 g/100 g (7); and oleic acid

(C18:1, n-9) with values from 25.38 g/100 g (34)

to 51.08 g/100 g (21). The fact that

these fatty acids predominate in meat of young and adult animals can be

explained by ruminant animals with endogenous synthesis in the adipocyte from

acetate, obtained during ruminal fermentation. This determines palmitic acid as

the main final product, later elongated into stearic acid or desaturated to

oleic acid. Long-chain fatty acids are easily synthesized in adipose tissue (17, 28).

While other

studies found no differences regarding fatty acid content concerning sex in

Nebrodi and Criollo Cordobes breeds (10, 34),

our study found the opposite effect with a greater amount of saturated fatty

acids; caproic, lauric, and myristic in male meat. While females have a higher

amount of oleic unsaturated fatty acid due to the above, males showed a higher

amount of saturated fatty acids and a lower amount of monounsaturated and

polyunsaturated fatty acids. These differences could be due to breed or diet,

since, even though kids are milk-fed, the lipid profile of the mother’s milk

will be largely determined by her diet (25).

Conclusions

Based on the

results, we conclude that kid morphometric characteristics are heterogeneous in

females and males in northeastern Mexico. Sex did not affect carcass

characteristics, nutritional value, and physicochemical traits of meat.

However, sex tended to modify FA profile, favoring a higher concentration of

caproic (C6:0), lauric (C12:0), myristic (C14:0), and oleic (C18:1, n-9) acids

in males.

This constitutes

a pioneer study on morphostructure, carcass, and meat quality characterization

of local goat kids from northeastern Mexico and will lay the foundations for

future programs to improve the production system. The differences found could

shed light on future efforts to differentiate kid meat from this region of

Mexico oriented to new markets that would directly benefit small producers.

Acknowledgements

We thank the

Colegio de Postgraduados- Livestock program for allowing us to carry out the

fatty acid profile of the meat sample in the gas chromatograph of its Animal

Nutrition laboratory.

1. Adzitey, F.;

Nurul H. 2011. Pale soft exudative (PSE) and dark firm dry (DFD) meats causes

and measures to reduce these incidences-a mini review. International Food

Research Journal. 18: 11-20.

2. Aguirre, L.;

Albito, O.; Abad-Guamán, R.; Maza, T. 2022. Determinación de la curva de

crecimiento en la cabra “Chusca Lojana” del bosque seco del Sur del Ecuador.

CEDAMAZ. 12(2): 125-129. https://doi.org/10.54753/cedamaz.v12i2.1216

3. Aktas, A. H.;

Gök, B.; Ates, S.; Tekin, M. E.; Halici, I.; Bas, H.; Erduran, H.; Kassam, S.

2015. Fattening performance and carcass characteristics of Turkish indigenous

Hair and Honamli goat male kids. Turkish Journal of Veterinary & Animal

Sciences. 39: 643-653. doi:10.3906/vet-1505-84

4. Alcalde, M.

J.; Suárez, M. D.; Rodero, E.; Álvarez, R.; Sáez, M. I.; Martínez, T. F. 2017.

Effects of farm management practices and transport duration on stress response

and meat quality traits of suckling goat kids. Animal. 11(9): 626-1635.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731116002858

5. Araújo, M.; Marcílio,

F.; Das- Graças, G. M.; Wandrick. H.; José, M. F.; Aldo, T. S.; Rayanna, C. F.

2017. Commercial cuts and carcass characteristics of sheep and goats

supplemented with multinutritional blocks. Revista MVZ Córdoba. 22(3):

6180-6190. https://doi.org/10.21897/rmvz.1123

6. Argüello, A.;

Castro, N.; Capote, J.; Solomon, M. 2005. Effects of diet and live weight at

slaughter on kid meat quality. Meat Science. 70(1): 173-179.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2004.12.009

7. Atti, N.;

Mahouachi, M.; Rouissi, H. 2006. The effect of spineless cactus (Opuntia

ficus-indica f. inermis) supplementation on growth, carcass, meat quality

and fatty acid composition of male goat kids. Meat Science. 73(2): 229-235.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2005.11.018

8. Bedotti, D.;

Gómez-Castro, A. G.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, M., Martos-Peinado, J. 2004.

Caracterización morfológica y faneróptica de la cabra colorada pampeana.

Archivos de Zootecnia. 53: 261-271.

https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/495/49520303.pdf

9. BOE (Boletín

Oficial del Estado). 2011. Resolución de 19 de diciembre de 2011 de la

Dirección General de Recursos Agrícolas y Ganaderos, por la que se aprueba la

guía del etiquetado facultativo de carne de cordero y cabrito. Núm. 314:

146362-146367. https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2016-12450

10. Bonvillani,

A.; Peña, F.; Domenech, V.; Polvillo, O.; García, P. T.; Casal, J. J. 2010.

Meat quality of Criollo Cordobes goat kids produced under extensive feeding

conditions. Effects of sex and age/weight at slaughter. Spanish Journal of

Agricultural Research. 8(1): 116-125. https://doi.org/10.5424/sjar/2010081-1150

11. CIE

(Commission Internationale de L’Eclairage). 1986. Colorimetry (2nd ed.).

Vienna.

12.

Dorantes-Coronado, E. J.; Torres-Hernández, G.; Hernández-Mendo, O.; Rojo-Rubio,

R. 2015. Zoometric measures and their utilization in prediction of live weight

of local goats in Southern Mexico. SpringerPlus. 4: 695. https://doi.org/10.

1186/s40064-015-1424-6

13. Ekiz, B.;

Ozcan, M.; Yilmaz, A.; Tölü, C.; Savaş, T. 2010. Carcass measurements and meat

quality characteristics of dairy suckling kids compared to an indigenous

genotype. Meat Science. 85(2): 245-249.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.01.006

14. El Moutchou,

N.; González, A. M.; Chentouf, M.; Lairini, K.; Rodero, E. 2017. Morphological differentiation

of Northern Morocco goat. Journal of Livestock Science and Technologies. 5(1):

33-41. https://doi.org/10.22103/JLST.2017.1662

15. Feng, S. A.;

Lock, L. A.; Garnsworthy, P. C. 2004. A rapid lipid separation method for

determining fatty acid composition of milk. Journal of Dairy Science. 11(87):

3785-3788. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(04)73517-1

16.

Granados-Rivera, L. D.; Hernández-Mendo, O.; González-Muñoz, S. S.;

Burgueño-Ferreira, J. A.; Mendoza-Martínez, G. D.; Arriaga-Jordán, C. M. 2017.

Effect of palmitic acid on the mitigation of milk fat depression syndrome

caused by trans-10, cis-12-conjugated linoleic acid in grazing dairy cows.

Archives of animal nutrition. 71(6): 428-440. https://doi.org/10.1080/1745039X.2017.1379165

17.

Granados-Rivera, L. D.; Hernández-Mendo, O. 2018. Síndrome de depresión de

grasa láctea provocado por el isómero trans-10, cis-12 del ácido linoleico

conjugado en vacas lactantes. Revisión. Revista mexicana de ciencias pecuarias.

9(3): 536-554. https://doi.org/10.22319/rmcp.v9i3.4337

18. Guerrero, L.

I.; Ponce, A. E.; Pérez, M. L. 2002. Curso práctico de tecnología de carnes y

pescado. Universidad Metropolitana Unidad Iztapalapa. D. F. México. 1: 171.

19. Guzmán, J.

L.; De La Vega, F.; Zarazaga, L. Á.; Argüello, H. A.; Delgado-Pertíñez, M.

2019. Carcass characteristics and meat quality of conventionally and

organically reared suckling dairy goat kids of the Payoya breed. Annals of

Animal Science. 19(4): 1143-1159. https://doi.org/10.2478/aoas-2019-0047

20. Horcada, A.;

Ripoll, G.; Alcalde, M. J.; Sañudo, C.; Teixeira, A.; Panea, B. 2012. Fatty

acid profile of three adipose depots in seven Spanish breeds of suckling kids.

Meat Science. 92(2): 89-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.04.018

21. Hulya, Y.;

Ekiz, B.; Ozcan, M. 2018. Comparison of meat quality characteristics and fatty

acid composition of finished goat kids from indigenous and dairy breeds.

Tropical Animal Health Production. 50: 1261-1269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-018-1553-3

22. Jenkins, T.

C. 2010. Technical note: Common analytical errors yielding inaccurate results

during analysis of fatty acids in feed and digesta samples. Journal of Dairy

Science. 93(3):1170-1174. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2009-2509

23. Kawęcka, A.;

Sikora, J.; Gąsior, R., Puchała, M.; Wojtycza, K. 2022. Comparison of carcass

and meat quality traits of the native Polish Heath lambs and the Carpathian

kids. Journal of Applied Animal Research. 50(1): 109-117.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09712119.2022.2040514

24. Liu, F.;

Meng, L.; Gao, X.; Li, X.; Luo, H.; Dai, R. 2012. Effect of end point

temperature on cooking losses, shear force, color, protein solubility and

microstructure of goat meat. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation.

37(3): 275-283. doi:10.1111/j.1745-4549.2011.00646.x

25. Madruga, M.

S.; Resosemito, F. S.; Narain, N.; Souza, W. H.; Cunha, M. G. G.; Ramos, J. L.

F. 2006. Effect of raising conditions of goats on physico-chemical and chemical

quality of its meat. CYTAJournal of Food. 5(2): 100-104.

https://doi.org/10.1080/11358120609487678

26.

Maldonado-Jáquez, J. A.; Arenas-Báez, P.; Garay-Martínez, J. R.;

Granados-Rivera, L. D. 2023. Body composition as a function of coat color, sex

and age in local kids from northern Mexico. Agrociencia.

https://doi.org/10.47163/agrociencia.v57i4.2916

27.

Marquínez-Bastita, L. M.; Saldaña-Ríos, C. I.; Moreno, E. E.; Rivera, R.;

Escudero, V.; Sandoya, I.; Espinosa, J.; Martínez, M. 2022. Caracterización de

la producción, agroindustrialización y comercialización de ovinos y caprinos en

Panamá. Ciencia Agropecuaria. 35: 30-52.

http://www.revistacienciaagropecuaria.ac.pa/index.php/ciencia-agropecuaria/article/view/594

28. Martinez, A.

L. M.; Alba, L. P.; Castro, G. G.; Hernández, M. P. 2010. Digestión de los

lípidos en los rumiantes: una revisión. Interciencia. 35(4): 240-246.

https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/339/33913156002.pdf

29. Patel, J.

V.; Srivastava, A. K.; Chauhan, H. D.; Gupta, J. P.; Gami, Y. M.; Patel, V. K.;

Madhavatar, M. P.; Thakkar, N. K. 2019. Factor affecting birth weight of

Mehsana goat kid at organized farm. International Journal of Current

Microbiology and Applied Sciences. 8(3): 1963-1967.

https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2019.803.000

30. Prado, D.

M.; Pozo, J. M. 2011. Acciones para potenciar el incremento de la producción y

comercialización de carne ovina por el municipio de Yaguajay. Economía y

Desarrollo. 146(1-2): 174-188.

https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=425541315011

31.

Salinas-González, H.; Maldonado, J. A.; Torres-Hernández, G.; Triana-Gutiérrez,

M.; Isidro-Requejo, L. M.; Meda-Alducin, P. 2015. Calidad composicional de la

leche de cabras locales en la Comarca Lagunera de México. Revista Chapingo

Serie Zonas Áridas. 14(2): 175-184. https://doi.org/10.5154/r.rchsza.2015.08.008

32. SIAP 2022.

¿Qué alimentos obtenemos de los caprinos o chivos? Consultado el 20 de agosto

del 2022. https://www.gob.mx/siap/articulos/caprinos-o-chivos

33. Teixeira,

A.; Jimenez-Badillo. M. R.; Rodrigues, S. 2011. Effect of sex and carcass

weight on carcass traits and meat quality in goat kids of Cabrito Transmontano.

Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research. (3): 753-760.

https://doi.org/10.5424/sjar/20110903-248-10

34. Todaro, M.;

Corrao, A.; Alicata, M. L.; Schinelli, R.; Giaccone, P.; Priolo A. 2004.

Effects of litter size and sex on meat quality traits of kid meat. Small

Ruminant Research. 54(3): 191-196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2003.11.011

35.

Vargas-López, S.; Bustamante-González, A.; Ramírez-Bribiesca, J. E.;

Torres-Hernández, G.; Larbi, A.; Maldonado-Jáquez, J. A.; López-Tecpoyotl, Z.

G. 2022. Rescue and participatory conservation of Creole goats in the

agro-silvopastoral systems of the Mountains of Guerrero, Mexico. Revista de la

Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza.

Argentina. 54(1): 153-162. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.074

36. Wang, Z.;

He, F.; Rao, W.; Ni, N.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, D. 2016. Proteomic analysis of goat

Longissimus dorsi muscles with different drip loss values related to meat quality

traits. Food Science and Biotechnology. 25: 425-431. https://doi.org

/10.1007/s10068-016-0058