Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 56(1). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2024.

Original article

Landform

heterogeneity drives multi-stemmed Neltuma flexuosa growth dynamics.

Implication for the Central Monte Desert forest management

La

heterogeneidad de paisaje modula la dinámica en el crecimiento de Neltuma

flexuosa. Implicancias para el manejo forestal de los bosques del Desierto

del Monte Central

1Laboratorio

de Dendrocronología e Historia Ambiental (IANIGLA CONICET). Av. Dr. Adrian Ruiz

Leal. Mendoza. M5500. Argentina.

2Universidad

Nacional de Cuyo. Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Cátedra de Dasonomía.

Almirante Brown 500 (M5528AHB). Chacras de Coria. Mendoza. Argentina.

3Universidad

Mayor. Facultad de Ciencias. Hémera Centro de Observación de la Tierra. Camino

La Pirámide 5750. Huechuraba. Santiago. Chile.

*spiraino@fca.uncu.edu.ar

Abstract

Drylands

represent the main earth biome, providing ecosytemic services to a large number

of people. Along these environments, woodlands are often dominated by

multi-stemmed trees, which are exploited by local inhabitants to obtain forest

products for their livelihood. In central-west Argentina, Neltuma flexuosa (algarrobo)

woodlands are distributed across different landform units, varying in

topographical and soil characteristics. This research aimed to reconstruct

stem-growth time until harvestable diameter was achieved, and biological

rotation age according to topo-edaphic variability in three algarrobo forests

using dendrochronological methods. Results indicated that landform heterogeneity

modulated species radial growth, influencing stem increments and cutting cycle

period. In this sense, a decreasing trend in tree productivity emerged along a

loamy-to-sandy textured soil gradient. These findings provide useful novel

information for N. flexuosa forest management, suggesting the need to

account for spatial landform/soil heterogeneity when examining desert forest

dynamics.

Keywords: arid woodlands,

forest management, growth form, tree-rings

Resumen

Las tierras

secas representan el principal bioma terrestre, proveyendo numerosos servicios

ecosistémicos a un ingente número de personas. En estos ambientes, los bosques

son a menudo dominados por árboles de porte multi-fustal, explotados por los

habitantes locales para obtener productos forestales útiles para su sustento.

En los territorios del centro-oeste de Argentina, los bosques de Neltuma

flexuosa (algarrobo) están distribuidos en diferentes unidades de paisaje,

los que presentan variaciones en las características topográficas y edáficas.

En este estudio reconstruimos, a través de métodos dendrocronológicos, el

crecimiento, el intervalo para obtener productos maderables, y el turno

biológico de corta en función de la variabilidad topo-edáfica en tres bosques

diferentes de algarrobo. Los resultados indican que la heterogeneidad del

paisaje modula el crecimiento radial de la especie, influenciando el incremento

diamétrico y el turno de corta. En este sentido, se evidencia una tendencia

decreciente en valores de productividad según un gradiente edáfico desde

textura limosa a arenosa. Estos hallazgos proveen información novedosa y de

utilidad para los planes de manejo forestal de los bosques de N. flexuosa,

indicando la necesidad por considerar la heterogeneidad

espacial establecidas por las unidades de paisaje/suelos en estudios

relativos a la dinámica forestal de los bosques de tierras secas.

Palabras claves:

bosques

de tierras secas, manejo forestal, forma de crecimiento, ancho de anillo

Originales: Recepción: 18/09/2023 - Aceptación: 14/04/2024

Introduction

Worldwide,

drylands represent the largest biome on Earth, covering more than 40% of land

surface (7, 29). These environments,

characterized by precipitation/evapotranspiration ratio below 0.2, include 20%

of plant diversity hotspots, play a fundamental role in various biogeochemical

cycles, and contribute to approximately 40% of global net primary productivity

(11, 16, 29).

Drylands host

more than two billion people (29). Along

these biomes, forests cover approximately 1.400 Mha, providing several

ecosystemic services like water and soil regulation, food, biochemical, and raw

material provision, as well as cultural services (7,

24). Physiognomically, many desert forests are dominated by tree species

capable of regeneration through development of new tissue following

disturbance, a physiological trait known as resprouting (8, 30). This results in vegetation with

coexisting one- and multi-stemmed trees, which differ in growth, productivity, reproduction,

and survival ability (30).

Dryland forests

have suffered various types of natural and anthropogenic disturbances, such as,

fire, insect outbreak, and drought, in addition to high deforestation rates due

to agricultural and livestock expansion (6, 20).

In this sense, it is estimated that, globally, about 220,000 km2 of

tree-covered drylands were converted into other land cover types between 1992

and 2015 (29). This suggests the need to

sustainably exploit and manage these natural resources, particularly in the

actual climate change scenario (16).

The Central

Monte Desert (hereafter, CMD) is a dryland biome located in central-west Argentina

(2). Along these districts, the algarrobo

dulce, Neltuma flexuosa (DC.) C.E. Hughes & G.P. Lewis (formerly designated

as Prosopis flexuosa DC), is a dominant tree species growing on a

variety of landform units (20). These

woodlands were severely exploited during the first half of the 20th

century, mainly for domestic wood demand, railway construction and, afterwards,

vineyard expansion, with a resulted extraction of approximately 1 million tons of

wood (1, 28).

Nowadays, the N.

flexuosa CMD forests are mostly managed by the local Huarpe native community,

through forestry practices that consider the typical low tree growth rates of these

woodlands (28). As a result, logging and

thinning are extremely rare activities in this area, whereas other

silvicultural approaches, such as pruning and deadwood removal, represent

valuable forest management alternatives (4, 27).

Pruning plays a prominent role due to the high presence of multi-stemmed trees

in CMD forests, as well as their higher productivity with respect to

one-stemmed individuals (3, 4).

Previous

analyses examined productivity in one- and multi-stemmed N. flexuosa trees,

providing valuable information regarding the CMD algarrobo forest management,

but solely at local scale (4). As

previously mentioned, the CMD N. flexuosa woodlands grow on a mosaic of

landform units, expression of soil variability and topographic characteristics

(21). This environmental heterogeneity is

reflected in differences of tree-ring development, as well as its relation with

precipitation regime and disturbance (21, 22).

It could be hypothesized, therefore, that the CMD landform variability would

represent a factor modulating multi-stemmed N. flexuosa tree

productivity, as well as stem-cutting cycle periods. Studying how topo-edaphic

characteristics influence multi-stemmed algarrobo growth dynamics can enhance

CMD silvicultural management by identifying landforms that can sustain intense

forest exploitation without ecological imbalance. For this reason, this

research analyzed stem growth rates of several multi-stemmed N. flexuosa trees

distributed along three different landform units, aiming to reconstruct

diametric cumulative increment, time (expressed in years) until forest products

can be obtained, and biological rotation age according to variations in

topography and soil characteristics of the CMD algarrobo forest stands.

Materials

and methods

In this study,

we examined three sites within the CMD located in the Province of Mendoza,

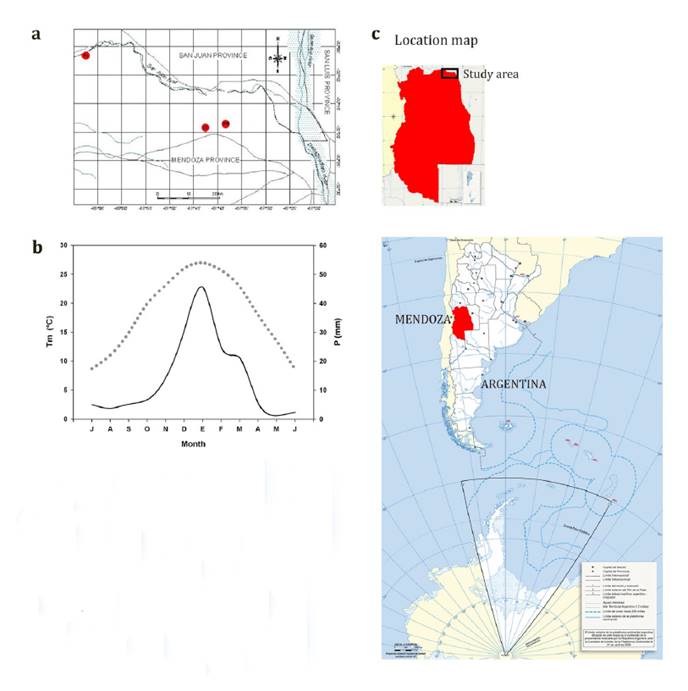

Argentina, representing distinct landform units (figure 1).

Monthly total precipitation (continuous line) and

monthly air temperature (dashed line) data belong to the Encón climatic station

(32°15’ S, 67°47’ W), covering the 1971-1987 period. RI, PR, and ID represent

River, Paleo-river, and Inter-dune valley units, respectively.

Los datos de precipitación media mensual (línea

continua) y temperatura promedio mensual (línea puntuada) pertenecen a la

estación meteorológica de Encón (32°15’ S, 67°47’ W), para el período

1971-1987. RI, PR, e ID representan respectivamente las unidades Riparia,

Paleo-riparia, y de Valle inter-medanoso.

Figure 1. Spatial

position of the sampled plots (a), climatic diagram (b), and geographical

location of the study area (c).

Figura 1. Ubicación

de los sitios de muestreo (a), diagrama climático (b), y localización

geográfica del área de estudio (c).

Along these

districts, the algarrobo woodlands grow under semi-arid climatic conditions,

with mean annual precipitation of 155 mm, and large variability in temperature

at both daily and seasonal timescales (2).

Vegetation consists of the typical CMD plant association, with N. flexousa dominating

the tree layer, occasionally accompanied by Geoffroea decorticans, along

with shrub presence of Larrea divaricata Cav., (Hook. And Arn.), Atamisquea

emarginata Miers ex Hook. & Arn and Bulnesia retama (Hook.)

Griseb (28).

Sites were selected

based on prior geomorphological classification (23).

In this study, River, Paleo-river, and Inter-dune valley landform units were

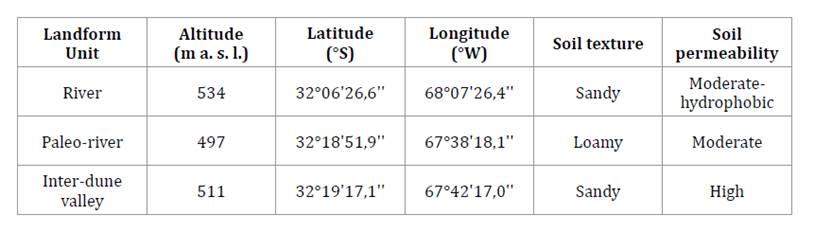

examined, differing in topographic characteristics and edaphic features (table 1).

Table

1. Geographical and environmental

characteristics of the sampled sites.

Tabla 1. Características

geográficas y ambientales de los sitios de muestreo.

m

a. s. l.: meters above sea level.

m

a. s. l.: metros sobre el nivel del mar.

The selected

algarrobo woodlands were in relative proximity (within 50 km), allowing us to

assume a common climatic influence upon the species stem growth. Soil types

varied among the examined stands, with sandy soils in the River and Interdune

valley units and loamy soils in the Paleo-river site (table 1).

On the other hand, soil permeability differed among the selected woodlands,

showing high to moderate and moderate-hydrophobic characteristics (table

1).

At each site,

1-2 rectangular plots of 1.000m2 (50m x 20m) were established to

examine the algarrobo forest dynamics in terms of tree radial growth relation

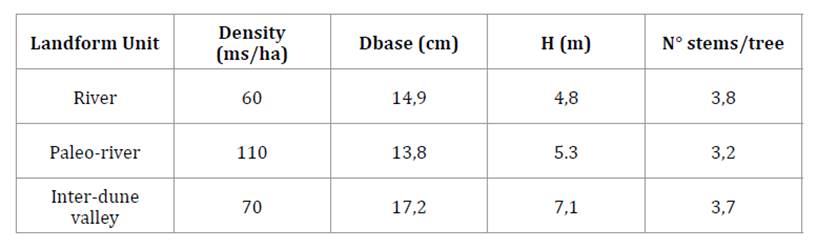

with rainfall and its response to thinning, results already published (21, 22). The examined stands exhibited variations

in structural characteristics, including differences in multi-stemmed tree density,

mean basal stem diameter, and tree height, whereas the number of stems per tree

was similar among the selected algarrobo forests (table 2).

Table

2. Stand structural characteristics of the

sampled sites.

Tabla 2. Características

estructurales de los sitios muestreados.

ms:

multi-stemmed tree. Dbase: mean multi-stemmed tree basal diameter; H: mean

multi-stemmed tree height.

ms:

árbol multi-fustal. Dbase: diámetro basal promedio del árbol multi-fustal. H:

altura promedio del árbol multi-fustal.

For each

multi-stemmed tree, two samples were extracted with a gas-powered drill

(TED_262R, Tanaka Kogyo Co. Ltd, Chiba, Japan), at approximately 50 cm above

the ground from the stem with the highest basal diameter. Samples were

air-drained, mounted on a wooden support, and polished with progressively finer

sandpaper to highlight wood anatomy. Rings were dated following the Schulman

criteria for the Southern Hemisphere tree species (25).

Tree-ring widths were measured from pith to bark with a 0.01 mm resolution Velmex

table connected to a computer. The correct dating of these measurements was

statistically validated with COFECHA software (13).

Then, we estimated individual tree diametric increments by averaging ring

measurements from samples belonging to each algarrobo tree and multiplying

these values by two. Finally, we calculated the cumulative diametric increment (CDI) as the sum of the current annual increments in diameter for each

biological year. This information allowed us

to estimate the time, in absolute tree age, required for the stem to reach the

minimum diameter corresponding to forest products in CMD algarrobo woodlands,

based on available information for the studied area (poles: stem ø= 10 cm) (19). When the core

center was not reached, tree age was estimated through a geometric method (10). We used ANOVA with

post-hoc Fisher’s least significant difference test through the Infostat software (9) to compare tree age

data across landform units. Five trees were excluded from this analysis since

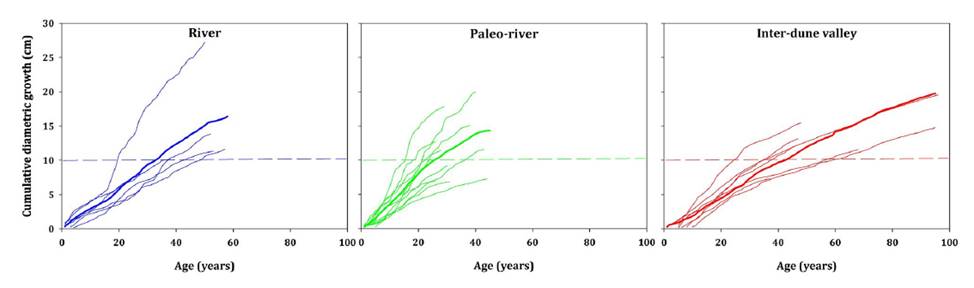

they did not reach minimum CDI values of 10 cm (figure 2).

Dashed horizontal lines show the minimum stem ø = 10

cm. / Las líneas puntuadas indican el ø mínimo del fuste = 10 cm.

Figure 2. Cumulative

diameter increment for the River, Paleo-river, and Inter-dune valley landform

units.

Figura 2. Crecimiento

diamétrico cumulativo para las unidades de paisaje de Ripario, Paleo-ripario, y

valle inter-medanoso.

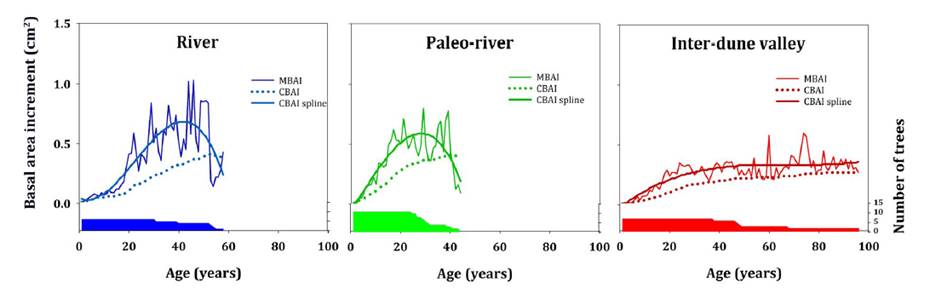

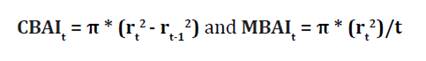

Biological

rotation age of the sampled algarrobo trees was estimated considering raw ring

widths converted to basal area increment (BAI). First, tree-ring measurements

from the two radii, corresponding to the two samples extracted for each tree,

were averaged at tree level to obtain individual ring-width chronologies. Then,

the AGE routine included in the DPL software

(Dendrochronological Program Library) (14) was

used to estimate current (CBAI) and mean (MBAI) basal area, according to the

following equation:

where:

rt represents ring

width in year t. Biological rotation age (cutting cycle period) was determined

at the age when MBAI and CBAI intersected (5).

Results

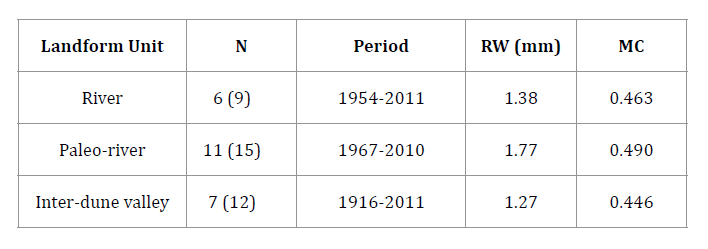

Tree-ring width

chronologies were constructed using 36 samples corresponding to 24 N.

flexuosa multi-stemmed trees. The relatively low number of selected trees

at River and Inter-dune valley depended on landowner sampling permission.

Multi-stemmed algarrobo site chronologies spanned from 44 (Paleo-river unit) to

96 years (Inter-dune valley unit). Mean annual radial growth rates oscillated

between 1.27 (Inter-dune valley unit) and 1.77 mm/yr (Paleo-river unit). Mean

correlation values (MC) between individual tree-ring chronologies ranked from

0.446 (Inter-dune valley unit) to 0.490 (Paleo-river unit), with all values

being significant at p < 0.05 (table 3).

Table

3. Characteristics of the tree-ring

chronologies.

Tabla 3. Características

de las cronologías de ancho de anillo.

N = Number of sampled trees per site (in

parenthesis: total number of dendrochronological samples); Period = time range

of the sampled cores; RW = mean ring-width value; MC = mean correlation between

individual tree-ring series at each stand.

N = número de los árboles muestreados (entre

paréntesis: número total de las muestras dendrocronológicas); Period =

intervalo temporal de las muestras; RW = valor de ancho de anillo promedio; MC

= correlación promedio entre las series dendrocronológicas individuales para

cada sitio.

CDI analysis

revealed that multi-stemmed trees achieved, on average, a minimum diameter of

10 cm at different ages: 37 years for River unit, 24 years for Paleo-river

environment, and 44 years for Inter-dune valley landform (figure

2).

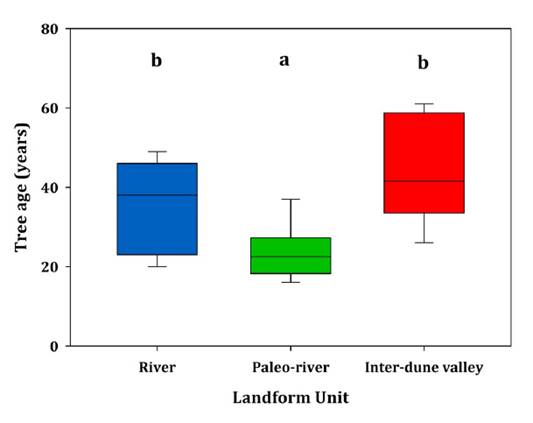

Statistically

significant differences emerged regarding tree age corresponding to CDI ø= 10

cm among Paleo-river units on one side, and River and Inter-dune valley

landforms on the other (one-way ANOVA, F = 5.40, p = 0.0161, df =

2, n = 19; figure 3).

Each box shows the values within one interquartile

distance (ID 25% above and below the median). The median is shown as a black

horizontal bar in the boxes. Whiskers represent values reaching 1.5 times the

IDs. Different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Cada caja muestra los valores comprendidos en la

distancia de un intercuartil (ID 25% por encima y por debajo del promedio). El

promedio se muestra como línea negra. Los bigotes corresponden a un valor de

1,5 veces la distancia de un ID y se muestran como líneas negras. Letras

diferentes indican diferencias significativas por p < 0,05.

Figure 3. Box

and whiskers plot for tree age corresponding to the minimum harvestable

diameter of 10 cm across landform units.

Figura 3. Gráficos

de caja-bigote para los valores del diámetro mínimo maderable de 10 cm según la

unidad de paisaje.

Landform

heterogeneity was reflected in biological rotation age among the selected

units. In this sense, the cutting cycle period occurred at ages 53 and 41 years

at River and Paleo-river units, corresponding to stem diameters of 19 and 18

cm, respectively. In contrast, at the Inter-dune valley landform, the

culmination age exceeded 96 years (stem ø = 24.5 cm), corresponding to the age

of the two oldest sampled trees (figure 4).

Coloured areas show the number of trees used for

estimating MBAI and CBAI.

Las áreas coloreadas indican el número de árboles

utilizados en el cálculo de MBAI y CBAI.

Figure 4. Mean

(MBAI) and current (CBAI) annual basal area increments in relation to tree ages

across landform units.

Figura 4. Incrementos

anuales en área basal promedio (MBAI) y corriente (CBAI) en relación a la edad

del árbol según la unidad de paisaje.

Discussion

In this study,

we employed dendrochronological methods to reconstruct growth dynamics of

multi-stemmed N. flexuosa across three distinct landform units within

the CMD. This research provides pioneering evidence of how topographical and

edaphic factors influence growth rates of multi-stemmed algarrobo trees in the

studied area. Our investigation delivered novel insights concerning the most

important forest resource that sustains local communities residing in arid

central-west Argentina. The low number of examined multi-stemmed N. flexuosa

individuals at two sites is not considered an analytic limitation, aimed to

explore for the first time tree growth form-dependent dynamics at regional

scale. Future studies increasing site repetitions as well total sampled tree

number could validate our findings.

Our analyses

demonstrated that landform variations were mirrored by growth rates of

multi-stemmed algarrobo trees, evidenced by differences in the time required to

attain harvestable stem diameters, and the length of the cutting cycle period.

Previous dendrochronological assessments suggested that soil attributes and

environmental heterogeneity play pivotal roles in shaping moisture availability

in the CMD districts, thereby influencing growth dynamics of algarrobo woodlands

(21). In this sense, it is worth

mentioning that N. flexuosa exhibits characteristics of a facultative

phreatophyte species, with distinctive root architecture that enables algarrobo

trees to access deep phreatic water while also exploring shallow soil horizons

(12). This trait allows N. flexuosa trees

to use both precipitation and groundwater for tree growth (15). Across the woodlands examined in our study,

the phreatic water table consistently lies at similar depths, approximately

between 4.5 and 6 meters (26), suggesting

that factors beyond water table accessibility, likely soil characteristics and

impact on water retention of superficial horizons, probably contributed to the

observed variations in tree growth. In arid ecosystems like the CMD, sandy

soils tend to facilitate deep water infiltration, whereas loamy edaphic layers

promote water retention in superficial horizons, resulting in enhanced stem

growth (17, 18, 21). Moreover, soil

permeability directly influences water storage capacity, with moderately

permeable soils exhibiting better precipitation retention compared to those

with higher permeability (18, 21). Both

of these edaphic attributes may collectively account for our research outcomes.

Previous

analyses have indicated that the biological rotation age of N. flexuosa is

growth-form dependent, with multi-stemmed trees reaching the cutting cycle

period at younger age than their one-stemmed counterparts (4). According to Alvarez et

al. (2011), multi-stemmed algarrobo trees could be harvested at

approximately 80 years of age. However, our study underscores that landform

clearly modulated the cutting cycle period. Our findings revealed different

values for biological rotation age across the examined stand. Regarding the

discrepancy observed for similar environments, that is, between the Inter-dune

valley stand analyzed in this research and the woodland examined by Alvarez et al. (2011), belonging to the same

landform unit, it could be hypothesized that variations in topographical

features, such as the presence (4) or

absence (our study) of a complete dune system surrounding the Inter-dune valley

site, may affect runoff processes and hence water availability. This landform

variability could potentially account for this particular divergent result,

although further investigations are warranted to explore the specific

topographic influence at a smaller spatial scale within the Inter-dune valley

unit, to address this difference more comprehensively.

At local scale,

our results indicated that wood extraction from multi-stemmed N. flexuosa in

CMD districts should consider landform heterogeneity. Specifically, while

multi-stemmed algarrobo trees in loamy Paleo-river soil and, to a lesser

extent, River units could be managed for pole production, pruning should be

avoided in Inter-dune valley N. flexuosa forest stands. This

recommendation is grounded in the exceptionally extended time required to reach

biological rotation age in this landform, which is approximately 100 years.

Additionally, the slow radial growth rates in the Inter dune valley environment

translated to an extended time window for obtaining forest products used by

local inhabitants in the studied area.

Conclusions

This research

sheds crucial light on a strategically vital forest resource for the

communities residing in the CMD area. These findings should be integrated with

the development of future forest management strategies for the semi-arid N.

flexuosa woodlands located in the central-western region of Argentina. On a

broader scale, our study underscores the paramount importance of considering

landform heterogeneity in the management of desert resprouting woody

vegetation.

Acknowledgments

The authors

warmly thank the Aguero and Cordoba families for allowing sampling in their

respective areas. Special thanks are due to Hugo Debandi and Alberto Ripalta

for field assistance. We thank the Direccion de Recursos Naturales Renovables

of Mendoza Province for allowing sampling.

1. Abraham, E.

M.; Prieto, M. R. 1999. Vitivinicultura y desertificación en Mendoza. En:

García Martínez, B. (Ed.), Estudios de historia y ambiente en América:

Argentina, Bolivia, México, Paraguay. IPGH-Colegio de México, México. 109-135.

2. Abraham, E.;

del Valle, H. F.; Roig, F.; Torres, L.; Ares, J. O.; Coronato, F.; Godagnone,

R. 2009. Overview of the geography of the Monte Desert biome (Argentina).

Journal of Arid Environments. 73(2): 144-153.

3. Alvarez, J.

A.; Villagra, P. E.; Cony, M. A.; Cesca, E.; Boninsegna, J. A. 2006. Estructura

y estado de conservación de los bosques de Prosopis flexuosa DC

(Fabaceae, subfamilia: Mimosoideae) en el noreste de Mendoza (Argentina).

Revista Chilena de Historia Natural. 79(1): 75-87.

4. Alvarez, J.

A.; Villagra, P. E.; Villalba, R.; Cony, M. A.; Alberto, M. 2011b. Wood

productivity of Prosopis flexuosa DC woodlands in the central Monte:

Influence of population structure and treegrowth habit. Journal of Arid

Environments. 75(1): 7-13.

5. Assman, E.

1970. The principles of forest yield study. Section B: Tree growth and form,

Pergamon Press. New York. 51-53.

6. Baldassini,

P.; Bagnato, C. E.; Paruelo, J. M. 2020. How may deforestation rates and

political instruments affect land use patterns and Carbon emissions in the

semi-arid Chaco, Argentina?. Land Use Policy. 99:

104985.

7. Bastin, J.

F.; Berrahmouni, N.; Grainger, A.; Maniatis, D.; Mollicone, D.; Moore, R.,

Patriarca, C.; Picard, N.; Sparrow, B.; Abraham, E. M.; Aloui, K.; Atesoglu,

A.; Attore, F.; Bassüllü, C.; Bey, A.; Garzuglia, M.; García-Montero, L. G.;

Groot, N.; Guerin, G.; Laestadius, L.; Lowe, A.; Mamane, B.; Marchi, G.;

Patterson, P.; Rezende, M.; Ricci, S.; Salcedo, I.; Sanchez-Diaz Paus, A.;

Stolle, F.; Surappaeva, V.; Castro, R. 2017. The extent of forest in dryland

biomes. Science. 356(6338): 635-638.

8. Bond, W. J.;

Midgley, J. J. 2001. Ecology of sprouting in woody plants: the persistence

niche. Trends in ecology & evolution. 16(1): 45-51.

9. Di Rienzo, J.

A.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M. G.; González, L.; Tablada, M.; Robledo, Y. C.

2011. InfoStat versión 2011. Grupo InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de

Córdoba, Argentina. http://www. infostat.com.ar. 8: 195-199.

10. Duncan, R.

P. 1989. An evaluation of errors in tree age estimates based on increment cores

in kahikatea (Dacrycarpus dacrydioides). New Zealand Natural Sci. 16:

31-37.

11. FAO (Food

and Agriculture Organization). 1977. Carte mondiale de la désertification a

l’échelle de 1:25,000,000, Conférence des Nations

Unies sur la désertification, 29 août–9 septembre, A/CONF. 74/2.

12. Guevara, A.;

Giordano, C. V.; Aranibar, J.; Quiroga, M.; Villagra, P. E. 2010. Phenotypic

plasticity of the coarse root system of Prosopis flexuosa, a

phreatophyte tree, in the Monte Desert (Argentina). Plant and soil. 330(1-2):

447-464.

13. Holmes R. L.

1983. Computer-assisted quality control in tree-ring dating and measurement.

Tree-Ring Bulletin. 43: 69-78.

14. Holmes, R.

L. 1999. Dendrochronological Program Library (DPL). User’s Manual, Laboratory

of Tree-Ring Research, University of Arizona. Tucson. Arizona. USA.

15. Jobbágy, E.

G.; Nosetto, M. D.; Villagra, P. E.; Jackson, R. B. 2011. Water subsidies from

mountains to deserts: their role in sustaining groundwater-fed oases in a sandy

landscape. Ecological Applications. 21(3): 678-694.

16. Maestre, F.

T.; Benito, B. M.; Berdugo, M.; Concostrina-Zubiri, L.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.;

Eldridge, D. J.; Guirado, E.; Gross, N.; Kéfi, S.; Le BagoussePinguet, Y.;

Ochoa-Hueso, R.; Soliveres, S. 2021. Biogeography of global drylands. New

Phytologist. 231(2): 540-558.

17. Massa, A.;

Quagliariello, G.; Martinengo, N.; Calderón, A.; Pérez, S. 2023. Growth and

slenderness index in sweet algarrobo, Neltuma flexuosa, according to the

vermicompost percentage in the substrate and seed origin. Revista de la

Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza.

Argentina. 55(2): 12-19. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.105

18. Noy-Meir, I.

1973. Desert ecosystems: environment and producers. Annual review of ecology

and systematics. 4: 25-51.

19. Ongay

Ugarteche, O.; Marambio Fermani. S.; Corominas Day, M.; Lagos Slinik, S.

Acordinaro N. 2011. Manual de Bosques Nativos. Un aporte a la Conservación

desde la Educación Ambiental. Dirección de Recursos Naturales Renovables

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente Gobierno de Mendoza. 121 p.

20. Petrie, M.

D.; Bradford, J. B.; Hubbard, R. M.; Lauenroth, W. K.; Andrews, C. M.;

Schlaepfer, D. R. 2017. Climate change may restrict dryland forest regeneration

in the 21st century. Ecology. 98(6): 1548-1559.

21. Piraino, S.;

Abraham, E. M.; Diblasi, A.; Roig Juñent, F. A. 2015. Geomorphological-related heterogeneity

as reflected in tree growth and its relationships with climate of Monte Desert Prosopis

flexuosa DC woodlands. Trees. 29: 903-916.

22. Piraino, S.;

Abraham, E. M.; Hadad, M. A.; Patón, D.; Roig-Juñent, F. A. 2017. Anthropogenic

disturbance impact on the stem growth of Prosopis flexuosa DC forests in

the Monte desert of Argentina: A dendroecological approach. Dendrochronologia.

42: 63-72.

23. Rubio, M.

C.; Soria, D.; Salomón, M. A.; Abraham, E. 2009. Delimitación de unidades

geomorfológicas mediante la aplicación de técnicas de procesamiento digital de

imágenes y SIG. Área no irrigada del departamento de Lavalle, Mendoza.

Proyección. 2: 1-33.

24. Schild, J.

E.; Vermaat, J. E.; van Bodegom, P. M. 2018. Differential effects of valuation

method and ecosystem type on the monetary valuation of dryland ecosystem

services: A quantitative analysis. Journal of arid environments. 159: 11-21.

25. Schulman, E.

1956. Dendroclimatic changes in semiarid America. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

26. Soria, D.;

Rubio, C.; Abraham, E. M. 2011. Sitio piloto en la Región Centro Oeste. En:

“Evaluación de la desertificación en Argentina. Resultados del proyecto

LADA/FAO”. FAO, PAN, UNEP, GEF, LADA y SAyDS. Gráfica Latina. Buenos Aires,

Argentina. 205-246.

27. Vázquez, D.

P.; Alvarez, J. A.; Debandi, G.; Aranibar, J. N.; Villagra, P. E. 2011.

Ecological consequences of dead wood extraction in an arid ecosystem. Basic and

Applied Ecology. 12(8): 722-732.

28. Villagra, P.

E.; Defossé, G. E.; Del Valle, H. F.; Tabeni, S.; Rostagno, M.; Cesca, E.;

Abraham, E. 2009. Land use and disturbance effects on the dynamics of natural

ecosystems of the Monte Desert: Implications for their management. Journal of

Arid Environments. 73(2): 202-211.

29. Wang, L.;

Jiao, W.; MacBean, N.; Rulli, M. C.; Manzoni, S.; Vico, G.; D’Odorico, P. 2022.

Dryland productivity under a changing climate. Nature Climate Change. 12(11):

981-994.

30. Ware, I. M.;

Ostertag, R.; Cordell, S.; Giardina, C. P.; Sack, L., Medeiros, C. D.; Inman,

F.; Litton, C. M.; Giambelluca, T.; John, G. P.; Scoffoni, C. 2022.

Multi-stemmed habit in tres contributes climate resilience in tropical dry

forest. Sustainability. 14(11). 6779.