Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 56(1). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2024.

Original article

Effect

of three different fixed-time AI protocols on folicular dynamics and pregnancy

rates in suckled, dual-purpose cows in the Ecuadorian Amazon

Efecto

de tres protocolos diferentes de IA a tiempo fijo sobre la dinámica folicular y

las tasas de preñez en vacas de doble propósito amamantando en la Amazonía

Ecuatoriana

Juan Carlos

López Parra1†,

Alejandro Javier

Macagno4, 5*,

1Ministerio

de Agricultura y Ganadería. Subsecretaría de desarrollo Pecuario. Centro

Nacional de Mejoramiento Genético y Productivo El Rosario. Ecuador.

2Universidad

Nacional de Rosario. Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias. Ovidio lagos y ruta 33

(2170). Argentina.

3Universidad

Nacional de Rosario. Carrera del Investigador Científico (CIC).

4

Instituto de Reproducción Animal Córdoba (IRAC). Zona Rural General Paz, C. P.

5145. Córdoba. Argentina.

5Universidad

Nacional de Villa María. Instituto A. P. de Ciencias Básicas y Aplicadas.

Medicina Veterinaria. Obispo Ferreyra 411. Villa del Rosario. Córdoba.

Argentina. C. P. 5963.

*macagno9@gmail.com

Abstract

Reproductive

performance is crucial for profitability of dual-purpose cow-calf production in

the Ecuadorian Amazon. To evaluate three different fixed-time artificial insemination

(FTAI) protocols in suckled, dual-purpose cows in the Ecuadorian Amazon.

Lactating, Brown Swiss cows (n=301) received 2 mg estradiol benzoate (EB) and

an intravaginal device containing 0.5 g of progesterone (P4) on Day 0. They

were allocated randomly into the following three treatment groups: Cows in the

EB group received 500 μg cloprostenol (PGF2α), and P4 devices were removed on

Day 7, and 1 mg EB was administered on Day 8. Cows in the ECP group were

treated as those in the EB group, except that they received 0.5 mg estradiol

cypionate (ECP) at the time of P4 device removal on Day 7 instead of EB on Day

8. Cows in the J-Synch group had the P4 device removed and PGF2α administered

on Day 6. All cows were FTAI on Day 9; cows in the J-Synch group also received

100 μg gonadorelin at that time. Although the diameter of the dominant follicle

and the resulting CL were greater (P<0.05) in cows in the J-Synch group,

pregnancies per AI did not differ (P>0.2) among groups (EB: 51.0%, ECP:

53.0% and J-Synch: 59.4%). The three protocols tested were applied successfully

in suckled, dual-purpose cows with no differences in pregnancies per AI.

Keywords: prolonged

proestrus, estradiol/progesterone, P4 device, FTAI, pregnancy per AI, lactating

dual-purpose cows, tropical

Resumen

El desempeño

reproductivo es crucial para la rentabilidad de la producción doble propósito

en la Amazonía Ecuatoriana. Evaluar tres protocolos para Inseminación

Artificial a tiempo fijo (IATF) en vacas en lactancia de doble propósito. Vacas

Pardo Suizo en lactancia (n=301) recibieron 2 mg de benzoato de estradiol (EB)

y un dispositivo intravaginal con 0,5 g de progesterona (P4) el Día 0 y fueron

asignadas aleatoriamente en tres grupos. Las vacas del grupo EB recibieron 500

μg de cloprostenol (PGF2α) y se les retiró el dispositivo el Día 7, y

recibieron 1 mg de EB el Día 8. Las vacas del grupo ECP fueron tratadas como

las del grupo EB, excepto que recibieron 0,5 mg de cipionato de estradiol (ECP)

en el día del retiro del dispositivo (Día 7) en lugar de EB el Día 8. En las

vacas del grupo J-Synch, el retiro del dispositivo y la administración de PGF2α

se realizaron el Día 6. Todas las vacas fueron IATF el Día 9 y las del grupo

J-Synch recibieron 100 μg de gonadorelina en ese momento. Aunque el diámetro

del folículo dominante y del CL fueron mayores (P<0,05) en las vacas del

grupo J-Synch, las tasas de preñez a la IATF no difirieron entre los grupos

(EB: 51,0%, ECP: 53,0% y J-Synch: 59,4%). Los tres protocolos probados se

pueden aplicar con éxito en vacas de doble propósito amamantando.

Palabras clave: proestro

prolongado, estradiol/progesterona, dispositivo de P4, IATF, preñez por

IA, vacas doble propósito en lactancia,

tropical

Originales:

Recepción: 13/10/2023 - Aceptación: 09/05/2024

Introduction

Dual-purpose

cattle production (i.e., milk and meat) represents a main source of

income for small farms in tropical areas around the world, such as the

Ecuadorian Amazon. However, there is a need for improvement in terms of

reproductive performance and genetics in dual-purpose livestock (31). Less-than-optimal efficiency is due to

multiple factors, including the environment (high temperature and humidity),

nutrition, health, management, and poor animal welfare, among others (31). One of the technologies that has had the

greatest impact on reproductive performance in beef and dairy cattle has been

the systematic application of artificial insemination (AI), without estrus

detection, known as fixed-time AI (FTAI) (4).

Currently, there is a wide range of FTAI protocols used in beef and dairy

cattle (4, 15, 47) which requires testing

in dual-purpose cattle in the Ecuadorian Amazon. FTAI protocols are classified

according to the main hormones used. Ovsynch-type protocols are based on the

use of GnRH and prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α; 35, 47)

and may be combined with the use of an intravaginal progesterone (P4) releasing

device in beef (26, 29) and dairy cattle

(41). Estradiol and P4-based protocols (2, 30) have also been commonly used for FTAI in

beef and dairy cattle, especially in South America (3,

4, 48). This treatment has been simplified by the administration of

estradiol cypionate (ECP) as an ovulation-inducing agent, given at the time of

P4 device removal (14) replacing the use

of estradiol benzoate (EB) 24 h after P4 device removal in beef (14, 44) and dairy cattle (40, 42). In general, both FTAI protocols

(GnRH-based and estradiol/P4-based) result in pregnancies per AI (P/AI) between

40 to 60% in beef (1, 5) and 30 to 50% in

dairy cattle (15, 43). In 2012, a new

estradiol/P4-based protocol, called J-Synch, was developed (19). In this treatment protocol, the P4-releasing

device is inserted for a shorter period of time (6 days) and the administration

of ECP at the time of P4 device removal was replaced by the administration of

GnRH at the time of AI (72 h after P4 device removal), promoting a longer

proestrous period. Subsequent studies have shown that the J-Synch protocol is

an efficient treatment to synchronize ovulation in beef (19, 32) and dairy (36)

heifers, resulting in greater pregnancy rates than those achieved with the

conventional estradiol/P4-based protocols which used ECP or EB to induce

ovulation (5, 20, 36). The higher

pregnancy rates obtained with the J-Synch protocol were associated with longer

exposure to elevated endogenous estradiol concentrations during the proestrus

period, which resulted in a more appropriate environment for early embryo

development (20).

The current

experiment was designed to evaluate three different estradiol/P4-based FTAI

protocols, which differ mainly in the duration of the proestrus period, in

suckled dual-purpose cows of the Ecuadorian Amazon. The hypothesis to be tested

was that the protocol with the prolonged proestrus and utilizing GnRH to induce

ovulation, named J-Synch, would result in greater P/AI than conventional

estradiol/P4 protocols, which utilized EB or ECP to induce ovulation.

Materials

and methods

The study was

performed in the Ecuadorian Amazon, at the Center of Postgraduate Research and Conservation

of the Amazon (CIPCA) of the Amazon State University in the province of Napo,

which is located in the Northeast of Ecuador (Latitude: 01°14’32” South,

Longitude: 53°77’13” West), from October 2015 to April 2016. The climate is

tropical, with 4000 mm of precipitation per year, average relative humidity of

80% and temperatures ranging between 25 and 30°C. The altitude varies from 580

to 990 m above sea level, and although the soils have a very heterogeneous

composition, most originated in fluvial sediments from the Andean plateaus.

Animals

and feeding

Lactating, Brown

Swiss cows (n = 301) with suckling calves were used. The study was performed in

three replicates of 100 animals each. Cows were grazing a mixed pasture based

on Brachiaria decumbens (17.585 kg DM/ha/year), Brachiaria brizantha (26.970

kg DM/ha/year), Arachis pinto (6.212 kg DM/ha/year), Desmodium

ovalifolium (5.890 kg DM/ha/year) and Stylosanthes guianensis (15.237

kg DM/ha/year). They received the standard vaccination and health protocols

applied commonly to cattle at the CIPCA. This included the application of

vitamins and minerals, deworming, insecticide dips against ticks and flies,

vaccinations for Foot and Mouth Disease, Bovine Rabies and Vesicular

Stomatitis. The cows were multiparous (i.e., 2-5 lactations), 112.0±1.0

(mean±SEM) days postpartum, with a mean body condition score (BCS) of 2.4±0.3

(1 to 5 scale; 22), and they were producing 6.7±0.6 Kg of milk per day. Cows

were selected for treatment by the presence of a CL, or at least one follicle

>10 mm in diameter in their ovaries through an ultrasound examination and

without any abnormalities of the reproductive tract. All cows were handled in

the same milking facility and were inseminated with frozen-thawed semen from one

bull of proven fertility. Animal procedures were approved and supervised by the

Animal Care and Use Committee of the CIPCA and the Institutional Committee for

the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (CICUAL) of the University of Villa

Maria (UNVM), Argentina.

Treatments

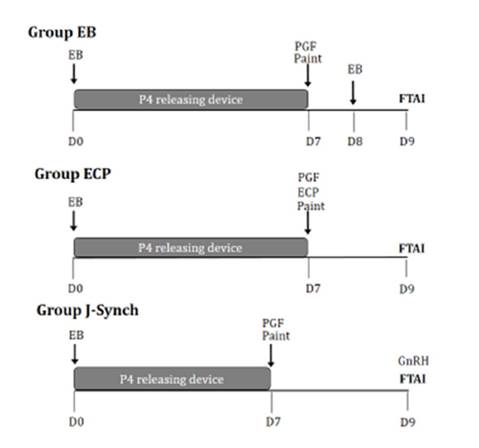

Cows were

randomly allocated to one of three FTAI protocols. The EB protocol (n = 100):

On Day 0, cows received a P4-releasing intravaginal device (DIB 0.5 g, Zoetis,

Ecuador) plus 2 mg EB (Gonadiol, Zoetis) by intramuscular (i.m.) injection. On

Day 7, the P4 device was removed, and cows received 500 μg cloprostenol (PGF2α,

Ciclase DL, Zoetis) i.m. On Day 8, all cows received 1 mg EB i.m. and the tail

heads were painted (Divasa - Farmavic, Spain) for the determination of estrus.

On Day 9, (48 to 54 h after P4 device removal) cows were FTAI (figure

1).

EB group: Day 0, P4 releasing device (0.5 g of P4)

plus 2 mg EB; Day 7 device removal plus 500 μg cloprostenol (PGF); Day 8, 1 mg

of EB; Day 9, FTAI (48 to 54 h after P4 device removal). ECP group: Day 0, P4

releasing device (0.5 g of P4) plus 2 mg EB; Day 7 device removal plus 500 μg

cloprostenol (PGF) and 0.5 mg ECP; Day 9, FTAI (48 to 54 h after P4 device

removal). J-Synch group: Day 0, P4 releasing device (0.5 g of P4) plus 2 mg EB;

Day 6 device removal plus 500 μg cloprostenol (PGF); Day 9, GnRH and FTAI (72 h

after device removal).

EB: Día 0, dispositivo liberador de P4 (0,5 g de P4)

más 2 mg de EB; Día 7, retiro del dispositivo más 500 μg de cloprostenol (PGF);

Día 8, 1 mg de EB; Día 9, IATF (48 a 54 h después de retirado el dispositivo de

P4). ECP: Día 0, dispositivo liberador de P4 (0,5 g de P4) más 2 mg de EB; Día

7, retiro del dispositivo más 500 μg de cloprostenol (PGF) y 0,5 mg de ECP; Día

9, IATF (48 a 54 h después de retirado el dispositivo de P4). J-Synch: Día 0,

dispositivo liberador de P4 (0,5 g de P4) más 2 mg de EB; Día 6, retiro del

dispositivo más 500 μg de cloprostenol (PGF); Día 9, GnRH y IATF (72 h después

de retirado el dispositivo de P4).

Figure 1. Treatment

Groups.

Figura 1. Grupos

de tratamiento.

The ECP protocol

(n = 100): On Day 0, cows received a P4 intravaginal device plus 2 mg of EB

i.m. On Day 7, the P4 device was removed, and cows received PGF2α and 0.5 mg

ECP (Cipiosyn, Zoetis) i.m. and the tail heads were painted as in the EB

protocol. On Day 9, (48 to 54 h after P4 device removal), cows were FTAI (figure 1).

The J-Synch

protocol (n = 101): On Day 0, cows received a P4 device plus 2 mg of EB i. m.

On Day 6, the P4 device was removed, cows received PGF2α i.m. and the tail

heads were painted as in the previous groups. On Day 9, (72 h after P4 device

removal), cows received 100 μg gonadorelin acetate (GnRH, Gonasyn gdr, Zoetis)

and were FTAI concurrently (figure 1).

Ultrasonography

All cows were

examined by real-time ultrasonography (Ibex Pro and Lyte ®, USA), with a linear

probe of 5.0 MHzon Days 7, 9 and 10. A map was made to measure and record all

follicles >5 mm present in both ovaries, and to identify the dominant follicle

which was defined as the follicle with the largest diameter at the time of

device removal. To determine the timing of ovulation (disappearance of the

follicle of greatest diameter) animals were examined at the time of FTAI (Day

9) and then every 12 h for the next 24 h. If the cows ovulated after Day 10,

the ovulation time was defined as an ovulation occurring > 24 h after FTAI.

The ovulation was reconfirmed by the presence of a CL 7 days after FTAI. Two

measurements of the CL were taken using the equipment’s software which included

the vertical and horizontal diameter (width and height) of each CL as described

previously (25).

Estrus

detection

Estrus was

recorded visually and by the disappearance of the tail-paint. The animals with

>30% of the paint removed were considered to be in estrus (13). The visual observations 3 times a day:

morning, noon and afternoon of Days 7, 8 and 9 were initiated after the removal

of the P4 device.

Blood

sampling and progesterone analysis

Seven days after

FTAI a blood sample was taken for P4 analysis. After cleaning and disinfecting

the base of the tail, samples were taken from the coccygeal vein using 10 mL

Vacutainer tubes. Samples were stored at the laboratory at 4°C for 4 to 6 h

after extraction and then centrifuged at 3000 RPM for 20 minutes to separate

the serum. The serum was extracted and then stored at -20°C until its

subsequent analysis (18). The serum P4

concentrations were determined together, in duplicates, using a progesterone

ELISA kit (Progesterone Elisa, DiaMetra S.R.L., Italy). The minimum detectable

P4 concentration of the kit was 0.05 ng/mL and the low and high intra-assay

coefficients of variation were 4.4% and 19.5%, respectively.

Pregnancy

diagnosis

The diagnosis of

pregnancy was determined by ultrasonography at 35 to 40 days after FTAI.

Statistical

analysis

For each

continuous variable studied, the arithmetic mean (x) and the standard error

(SEM) were estimated. The data were analyzed using ANOVA and means were

compared by the Tukey-Kramer HSD test. Differences were considered significant

with a P value of <0.05. The statistical analysis was carried out using the

JMP program (JMP ®, 2003) in its version 5.0 for

Windows. Estrus, ovulation and P/AI rates were compared among groups using

logistic regression for binary data (i.e., 1 = success, 0 = failure) and

a logit link, using the Infostat program (21).

Results

Estrus

expression

Overall, 90.4%

(272/301) of the cows showed estrus. The percentage of cows in estrus was lower

(P < 0.01) in the J-Synch treatment group (78.2%, 79/101), than in the ECP

(93%, 93/100) or EB (100%, 100/100) treatment groups.

Follicular

characteristics

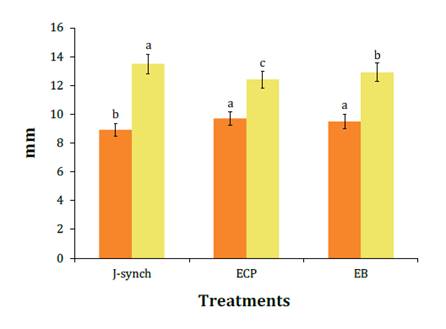

The diameters of

the dominant follicle at the time of P4 device removal and at the time of FTAI

are shown in figure 2. Cows in the J-Synch group had the

smallest mean diameter follicle at the time of P4 device removal and the

largest diameter follicle at the time of FTAI (P < 0.05).

abc

Different superscripts indicate significant differences between groups

(P<0.05).

abc

indica diferencias significativas entre grupos (P<0,05).

Figure 2.

Diameter of dominant follicle (means ± SEM) at the time of P4 device removal

(orange columns) and at the time of FTAI (yellow columns) in suckled,

dual-purpose cows subjected to three different estradiol/P4-based protocols.

Figura 2. Diámetro

del folículo dominante (media ± SEM) en el momento del retiro del dispositivo

P4 (columnas naranjas) y en la IATF (columnas amarillas) en vacas de doble

propósito sometidas a tres protocolos que utilizan estradiol/P4.

Time

of ovulation

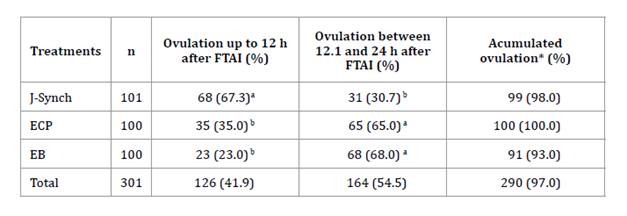

The mean

interval from P4 device removal to ovulation was longer (P < 0.01) in the

J-Synch group (87.7 ± 0.6 h) than in the ECP (73.7 ± 0.6 h) or EB (75.7 ± 0,6

h) groups. Overall, the percentage of cows that ovulated by 12 h after FTAI was

41.9% (126/301) and it was greater (P < 0.01) in the J-Synch group than in

the other two groups (table 1).

Table

1. Ovulatory response up to 12 h and

between 12.1 and 24 h after FTAI in suckled dual-purpose cows subjected to

three different estradiol/P4-based protocols.

Tabla 1. Respuesta

ovulatoria hasta 12 y entre 12.1 y 24 h después de la IATF en vacas de doble propósito

sometidas a diferentes protocolos que utilizan estradiol/P4.

Percentages with different superscripts differ (abP

<0.01). *Ovulations occurring within 24 h after FTAI.

Los porcentajes con diferentes superíndices indican

diferencias significativas (abP <0,01). *Ovulaciones que ocurren

dentro de las 24 h posteriores a la IATF.

Conversely, the

percentage of cows that ovulated between 12.1 and 24 h after FTAI was less in

the J-Synch group than in the EB and ECP treatment groups (P < 0.01). The

percentage of cows that ovulated more than 24 h after P4 device removal was 3%

(9/301) and all were in the EB treatment group (9%; P > 0.1).

CL

diameter and serum P4 concentration 7 days after FTAI

The CL diameter

was greater (P < 0.05) in cows in the J-Synch group compared to the

other two groups, which did not differ from one another (table 2).

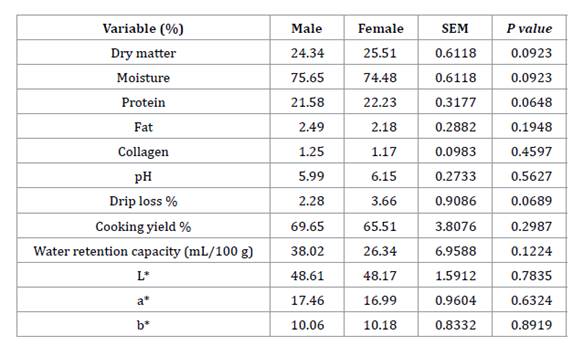

Table

2. CL diameter and serum progesterone

concentrations 7 days after FTAI (mean ± SEM) in suckled, dual-purpose cows

subjected to three different estradiol/P4-based protocols.

Tabla 2. Diámetro

del CL y concentración sérica de progesterona a los siete días de la IATF

(media ± SEM) en vacas de doble propósito sometidas a diferentes protocolos que

utilizan estradiol/P4.

Means within columns with different superscritps

differ (ab P < 0.05).

Las medias con diferentes superíndices indican

diferencias significativas (ab P < 0,05).

Similarly, serum

P4 concentrations were higher (P < 0.05) in the J-Synch group than in

the EB group but were intermediate in the ECP group which did not differ from

either of the other treatment groups (table 2).

Pregnancies

per FTAI (P/AI)

Overall, 164/301

(54.4%) of the cows were pregnant following FTAI. P/AI were numerically, but

not significantly higher (P<0.2) in cows in the J-Synch group (59.4%,

60/101), compared to the EB (51.0%, 51/100) and ECP (53.0%, 53/100) treatment

groups.

Another analysis

investigated the effects of the diameter of the dominant follicle at the time

of FTAI and the diameter of the ensuing CL on P/AI (table 3).

Table

3. Comparison of the follicular and luteal

characteristics in suckled, dual-purpose cows that became pregnant or did not

become pregnant following treatment with three different estradiol/P4-based

FTAI protocols (Mean ± SEM).

Tabla 3. Comparación

de las características foliculares y luteales entre vacas que quedaron preñadas

o no, en vacas de doble propósito sometidas a tres protocolos diferentes que

utilizan estradiol/P4 (media ± SEM).

*Pregnancy

Status: (P) pregnant; (O) non-pregnant.

*Estado

de gestación: (P) preñadas; (O) no preñadas.

Dominant

follicle diameter at the time of FTAI was greater (P < 0.01) in cows that

became pregnant than in those that did not become pregnant. Furthermore, the

diameter of the CL tended (P=0.0861) to be greater in cows that became pregnant

than in those that did not become pregnant to FTAI.

Discussion

The environment,

genetics, nutrition, health and management have been reported to be

determinants of the reproductive performance in cattle. Although the prolonged

proestrus protocol (J-Synch) resulted in the largest dominant follicle at the

time of FTAI and the largest CL 7 days after FTAI, the hypothesis that this

treatment results in greater P/AI than those in the conventional estradiol/P4

based protocols currently used in South America was not supported.

Nevertheless, the results of this study have important implications because

they demonstrate that other estradiol/P4-based FTAI alternatives can be applied

successfully in suckled dual-purpose cattle in tropical environments. The P/AI

exceeded 50% in the three treatment groups, which agrees with other studies

performed on beef cattle in tropical regions (1, 5,

27, 38), but superior to those reported with dairy cattle in the same

region (40, 46).

Another interesting

factor related to tropical regions is the low estrus expression rate and a

tendency to show estrus during the night, greatly affecting the efficiency of

AI programs (4). However, in the present

study, the overall estrus expression was 90.4%, which is higher than those

reported for beef and dairy cattle in tropical regions (15, 33, 38, 39). Several studies have shown that

the estrus expression at the time of FTAI, detected by tail-paint or estrus

detection patches is associated with greater P/AI (13,

33, 38, 39, 42, 43) suggesting that tail-paint or patches are useful

aids to determine that cows are indeed showing estrus at the time of FTAI,

which is likely to result in improved pregnancy outcomes following FTAI. The

duration of the proestrus period tended to have an influence on P/AI in this

study and has been reported to be positively related to an improved uterine

environment and fertility (7, 8, 9, 11).

Furthermore, the difference in dominant follicle diameter at P4 removal and at

the time of FTAI in this study agrees with a similar study reported by de la Mata et al. (2018), where cows receiving the

J-Synch treatment had the smallest follicles at P4 device removal, but had

follicles of the greatest diameter at the time of FTAI compared with two other

conventional (short proestrus) protocols. Although P/AI was only numerically

greater in cows in the J-Synch group, the cows that became pregnant, regardless

of treatment groups, had a greater follicle diameter at the time of FTAI than

those cows that did not become pregnant. This is also consistent with the

results reported by Yañez et al. (2016) on

dairy cows in Ecuador. It has also been reported that Bos taurus beef

heifers have the maximum probability of pregnancy when the follicular diameter

at the time of FTAI is >12.8 mm (34).

Furthermore, Bos indicus cows with follicles > 15 mm in diameter had

the greatest probability of ovulating and becoming pregnant in estradiol/P4

based FTAI programs (38, 39). Thus,

efforts to increase ovulatory follicle size would appear to be a worthy

endeavor.

When the time of

ovulation was evaluated in relation to the time of FTAI, the percentage of cows

ovulating up to 12 h after FTAI in J-Synch treatment group was the highest

(67.3%) compared to the ECP (35.0%) or EB (23.0%) treatment groups; while the

percentage of cows that ovulated between 12.1 and 24 h after FTAI was 30.7% for

the J-Synch treatment, and 65.0% and 68.0% for the ECP and EB treatment groups,

respectively. The determination of the percentage of cows ovulating 12, 24 and

after 24 h from FTAI may have important implications for fertility to FTAI

programs. It has been estimated that the maximum sperm viability in the female

genital tract is 24 to 30 h (23) and

after ovulation occurs, the oocyte has an even shorter fertile lifespan (6). Therefore, achieving greater synchrony

between ovulation and sperm arrival in the oviduct is very likely to increase

P/AI (37). Although pregnancy rates did

not differ among groups, inseminating cows nearer to the time of ovulation may

have given an advantage to the J-Synch group; however, results did not differ

significantly and increasing P/AI in the ECP and EB groups may have been due to

later ovulations within 24 h after FTAI, which is still considered appropriate

in cattle (16). In this study CL size 7

days after FTAI was greater in the J-Synch treatment group than in the other

groups, which is in agreement with the results reported by de la Mata et al. (2018). Nevertheless, it is

important to note that when all cows were considered, regardless of their

treatment, those that became pregnant had larger dominant follicles and tended

to have larger CL than those that did not become pregnant, which is in

agreement with other studies (12, 45).

Thus, larger ovulatory follicles should result in larger CL and greater P/AI

regardless of FTAI treatment protocol, again making this a worthy endeavor.

Endocrine and uterine environments associated with elevated estradiol

concentrations before ovulation have been reported to affect the maintenance of

the conceptus (9). Furthermore, preovulatory estradiol

concentrations have been reported to have a positive impact on subsequent

conceptus development (17). Therefore,

the positive relationship between the expression of estrus, follicle diameter,

plasma P4 concentration and P/AI may be explained by the effects of estradiol

and P4 on the endometrial tissue, as has been shown in other studies (10, 20, 24, 28).

Conclusions

Although the

prolonged proestrus protocol (J-Synch) resulted in the largest dominant

follicle at the time of FTAI and the largest CL 7 days after ovulation, P/AI

did not differ from the other estradiol/P4-based treatments in dual-purpose

cows. Nevertheless, the present study has shown a positive association between

the manifestation of estrus, follicle diameter at the time of FTAI and CL

diameter 7 days later in suckled dual-purpose cows synchronized with

estradiol/P4-based protocols for FTAI. Finally, it is concluded that the three

protocols tested can be successfully applied in lactating dual-purpose cows in

the Ecuadorian Amazon.

1. Baruselli, P.

S.; Reis, E. L.; Marques, M. O.; Nasser, L. F.; Bó, G. A. 2004. The use of

hormonal treatments to improve reproductive performance of anestrous beef

cattle in tropical climates. Animal Reproduction Science. 82-83: 479-486. DOI:

10.1016/j.anireprosci.2004.04.025

2. Bó, G. A.;

Adams, G. P.; Pierson, R. A.; Mapletoft, R. 1995. Exogenous control of

follicular wave emergence in cattle. Theriogenology. 43: 31-40. DOI: 10.1016/0093-691X(94)00010-R

3. Bó, G. A.;

Baruselli, P. S.; Martı́nez, M. F. 2003. Pattern and manipulation of follicular

development in Bos indicus cattle. Animal Reproduction Science. 78: 307-326.

DOI: 10.1016/S0378-4320(03)00097-6

4. Bó, G. A.;

Baruselli, P. S.; Mapletoft, R. J. 2013. Synchronization techniques to increase

the utilization of artificial insemination in beef and dairy cattle. Animal

Reproduction. 10: 137-142. DOI: 10.1017/S1751731114000822

5. Bó, G. A.; de

la Mata, J. J.; Baruselli, P. S.; Menchaca, A. 2016. Alternative programs for

synchronizing and re-synchronizing ovulation in beef cattle. Theriogenology.

86: 388-396. DOI: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2016.04.053

6. Brackett, B.

G.; Oh, Y. K.; Evans, J. F.; Donawick, W. J. 1980. Fertilization and early

development of cow ova. Biology of Reproduction. 23: 189-205. DOI:

10.1095/biolreprod23.1.189

7. Bridges, G.

A.; Hesler, L. A.; Grum, D. E.; Mussard, M. L.; Gasser, C. L.; Day, M. L. 2008.

Decreasing the interval between GnRH and PGF2α from 7 to 5 days and lengthening

proestros increases timad-IA pregnancy rates in beef cow. Theriogenology. 69:

843-851. DOI: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2009.05.002

8. Bridges, G.

A.; Mussard, M. L.; Burke, C. R.; Day, M. L. 2010. Influence of the length of

proestros on fertility and endocrine function in female cattle. Animal

Reproduction Science. 117: 208-2154. DOI: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2009.05.002

9. Bridges, G.

A.; Ahola, J. K.; Brauner, C.; Cruppe, L. H.; Currin J. C.; Day, M. L.; Gunn,

P. J.; Jaeger, J. R.; Lake, S. L.; Lamb, G. C.; Marquezini, G. H. L.; Peel, R.

K.; Radunz, A. E.; Stevenson, J. S.; Whittier, W. D. 2012. Determination of the

appropriate delivery of prostaglandin F2α in the five-day CO-Synch + controlled

intravaginal drug release protocol in suckled beef cows. Journal of Animal

Science. 90: 4814-4822. DOI: 10.3168/jds.2013-6845

10. Bridges, G.

A.; Day, M. L.; Geary, T. W.; Cruppe, L. H. 2013a. Deficiencies in the uterine

environment and failure to support embryonic development. Journal of Animal

Science. 91: 3002-3013. DOI: 10.2527/jas.2013-5882

11. Bridges, G.

A.; Mussard, M. L.; Helser, L. A.; Day, M. L. 2013b. Dynamics and hormone

concentrations between the 7-day and 5-day CO-Synch + CIDR program in

primiparous beef cows. Theriogenology. 81: 632-638. DOI:

10.1016/j.theriogenology.2013.11.020

12. Busch, D.

C.; Atkins, J. A.; Bader, J. F.; Schafer, D. J.; Patterson, D. J.; Geary, T.

W.; Smith, M. F. 2008. Effect of ovulatory follicle size and expression of

estrus on progesterone secretion in beef cows. Journal of Animal Science. 86:

553-563. DOI: 10.2527/jas.2007-0570

13. Cedeño, A.

V.; Cuervo, R.; Tríbulo, A.; Tríbulo, R.; Andrada, S.; Mapletoft, R.; Menchaca,

A.; Bó, G. A. 2021. Effect of expression of estrus and treatment with GnRH on

pregnancies per AI in beef cattle synchronized with an

oestradiol/progesterone-based protocol. Theriogenology. 161: 294-300. DOI:

10.1016 /j.theriogenology .2020.12.014

14. Colazo, M.

G.; Kastelic, J. P.; Mapletoft, R. J. 2003. Effects of oestradiol cypionate

(ECP) on ovarian follicular dynamics, synchrony of ovulation, and fertility in

CIDR-based, fixedtime AI programs in beef heifers. Theriogenology. 60: 855-865.

DOI: 10.1016/S0093-691X(03)00091-8

15. Cosentini,

C. E. C.; Wiltbank, M. C.; Sartori, R. 2021. Factors that optimize reproductive

efficiency in dairy herds with emphasis on timed artificial insemination

programs. Animals. 11: 301-331. DOI: 10.3390/ani11020301

16. Dalton, J.

C.; Nadir, S.; Bame, J. H.; Noftsinger, M.; Nebel, R. L.; Saacke, R. G. 2001.

Effect of time of insemination on number of accessory sperm, fertilization

rate, and embryo quality in nonlactating dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 84:

2413-2418. DOI: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(01)74690-5

17. Davoodi, S.;

Cooke, R. F.; Fernandes, A. C.; Cappellozza, B. I.; Vasconcelos, J. L.; Cerri,

R. L. 2016. Expression of estrus modifies the gene expression profile in

reproductive tissues on day 19 of gestation in beef cows. Theriogenology. 85:

645-655. DOI: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2015.10.002

18. de Castro,

T.; Valdez, L.; Rodríguez, M.; Benquet, N.; Rubianes, E. 2004. Decline in

assayable progesterone in bovine serum under different storage conditions.

Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 36: 381-384. DOI: 10.1023/b:trop.0000026669.06351.26

19. de la Mata,

J. J.; Bó, G. A. 2012. Sincronización de celos y ovulación utilizando

protocolos de benzoato de oestradiol y GnRH en periodos reducidos de inserción

de un dispositivo con progesterona en vaquillonas para carne. Taurus.

55: 17-23.

20. de la Mata,

J. J.; Nuñez-Olivera, R.; Cuadro, F.; Bosolasco, D.; de Brun, V.; Meikle, A.;

Bó, G. A.; Menchaca, A. 2018. Effects of extending the length of pro-oestrus in

an ooestradioland progesterone-based oestrus synchronisation program on ovarian

function, uterine environment, and pregnancy establishment in beef heifers.

Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 30: 1541-1552. DOI: 10.1071/RD17473

21. Di Rienzo,

J. A.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M. G.; Gonzalez, L.; Tablada, M.; Robledo, C.

W. InfoStat versión 2020. Grupo InfoStat, F.C.A., Universidad Nacional de

Córdoba, Argentina. URL http://www.infostat.com.ar

22. Edmonsond,

A. J.; Lean, I. J. 1989. A body condition scoring chart for Holando dairy cows.

Tulare 93274 Journal of Dairy Science. 72: 68-78. DOI:

10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(89)79081-0

23. Hiers, E.;

Barthle, C.; Dahms, V.; Portillo, G.; Bridges, G.; Rae, D.; Thacher, W.;

Yelich, J. 2003. Synchronization of Bos indicus x Bos taurus cows for

timed artificial insemination using gonadotropin-releasing hormone plus

prostaglandina F2α in combination with melegestrol acetate. Journal Animal

Science. 81: 830-835. DOI: 10.2527/2003.814830x

24. Jinks, E.

M.; Smith, M. F.; Atkins, J. A.; Pohler, K. G.; Perry, G. A.; MacNeil, M. D.;

Roberts, A. J.; Waterman, R. C.; Alexander, L. J.; Geary, T. W. 2013.

Preovulatory oestradiol and the establishment and maintenance of pregnancy in

suckled beef cows. Journal Animal Science. 91: 1176-1185. DOI:

10.2527/jas.2012-5611

25. Kastelic, J.

P.; Bergefelt, D. R.; Ginther, O. J. 1990. Relationship between ultrasonic

assessment of the corpus luteum and plasma progesterone concentration in

heifers. Theriogenology. 33: 1269-1278. DOI: 10.1016/0093-691X(90)90045-U

26. Lamb, G. C.;

Stevenson, J. S.; Kesler, D. J.; Garverick, H. A.; Brown, D. R.; Salfen, B. E.

2001. Inclusion of an intravaginal progesterone insert plus GnRH and

prostaglandin F2α for ovulation control in postpartum suckled beef cows.

Journal of Animal Science. 79: 2253-2259. DOI: 10.2527/2001.7992253x

27. Madureira,

G.; Consentini, C.; Motta, J.; Drum, J.; Prata, A.; Monteiro, P.; Melo, L. F.;

Gonçalves, J.; Wiltbank, M.; Sartori, R. 2020. Progesterone-based timed AI

protocols for Bos indicus cattle II: Reproductive outcomes of either EB or

GnRH-type protocol, using or not GnRH at AI. Theriogenology. 145: 86-93. DOI:

10.1016/j.theriogenology.2020.01.033

28. Mann, G. E.

2009. Corpus luteum size and plasma progesterone concentrations in cows. Animal

Reproduction Science. 115: 296-299. DOI: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2008.11.006

29. Martínez, M.

F.; Kastelic, J. P.; Adams, G. P.; Janzen, E.; McCartney, D.; Mapletoft, R. J.

2000. Estrus synchronization and fertility in beef cattle given a CIDR and

oestradiol or GnRH. Can. Vet. J. 41: 786-790. PMCID: PMC1476379 PMID: 11062836

30. Martínez, M.

F.; Kastelic, J. P.; Bó, G. A.; Caccia, M.; Mapletoft, R. J. 2005. Effects of

ooestradiol and some of its esters on gonadotrophin release and ovarian

follicular dynamics in CIDRtreated beef cattle. Anim Reprod Sci. 86: 37-52.

DOI: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2004.06.005

31. Moyano, J.

C.; López, J. C.; Vargas, J.; Quinteros, O. R.; Marini, P. R. 2015.

Plasmaspiegel von LH (luteinisierendes Hormon), Brunstsymptome und Qualität der

Gelbkörper in verschiedenen Protokollen, zur Synchronisation der Brunst in

Brown-Swiss-Milchrindern. Züchtungskunde. 87(4): 265-271.

32. Nuñez-Olivera,

R.; Bó, G. A.; Menchaca, A. 2022. Association between length of proestrus,

follicular size, estrus behavior, and pregnancy rate in beef heifers subjected

to fixedetime artificial insemination. Association between length of proestrus,

follicular size, estrus behavior, and pregnancy rate in beef heifers subjected

to fixedetime artificial insemination. Theriogenology. 181: 1-7. DOI:

10.1016/j.theriogenology.2021.12.028

33. Pereira, M.

H. C.; Wiltbank, M. C.; Vasconcelos, J. L. M. 2016. Expression of estrus

improves fertility and decreases pregnancy losses in lactating dairy cows that

receive artificial insemination or embryo transfer. Journal Dairy Science. 99:

237-2247. DOI: 10.3168/jds.2015-9903

34. Perry, G.

A.; Smith, M. F.; Roberts, A. J.; MacNeil, M. D.; Geary, T. W. 2007.

Relationship between size of the ovulatory follicle and pregnancy success in

beef heifers. J. Anim. Sci. 85: 684-519. DOI: 10.2527/jas.2006-519

35. Pursley, J.

R.; Mee, M. O.; Wiltbank, M. C. 1995. Synchronizatión of ovulation in dairy

cows using PGF2α and GnRH. Theriogenology. 44: 915-923. DOI: 10.1016/0093-691x(95)00279-h

36. Ré, M. G.;

Racca, G.; Filippi, L.; Veneranda, G.; Bó, G. A. 2021. Sincronización de la

ovulación y tasas de preñez en vaquillonas lecheras tratadas con protocolos que

prolongan el proestro. Taurus. 91: 28-45.

37. Saacke, R.

G.; Dalton, J. C.; Nadir, S.; Nebel, R. L.; Bame, J. H. 2000. Relationship of

seminal traits and insemination time to fertilization rate and embryo quality.

Animal Reproduction Science. 60-61: 663-677. DOI: 10.1016/s0378-4320(00)00137-8

38. Sá Filho, M.

F.; Crespilho, A. M.; Santos, J. E. P.; Perry, G. A.; Baruselli, P. S. 2010.

Ovarian follicle diameter at timed insemination and estrous response influence

likelihood of ovulation and pregnancy after estrous synchronization with

progesterone or progestin-based protocols in suckled Bos indicus cows. Animal

Reproduction Science. 120: 23-30. DOI: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2010.03.007

39. Sá Filho, M.

F.; Santos, J. E. P.; Ferreira, R. M.; Sales, J. N. S.; Baruselli, P. S. 2011.

Importance of estrus on pregnancy per insemination in suckled Bos indicus cows

submitted to oestradiol/progesterone based timed insemination protocols.

Theriogenology. 76: 455-463. DOI: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2011.02.022

40. Souza, A.

H.; Viechnieski, S.; Lima, F. A.; Silva, F. F.; Araujo, R.; Bó, G. A.;

Wiltbank, M. C.; Baruselli, P. S. 2009. Effects of equine chorionic

gonadotropin and type of ovulatory stimulus in a timed-AI protocol on

reproductive responses in dairy cows. Theriogenology. 72: 10-21. DOI:

10.1016/j.theriogenology.2008.12.025

41. Stevenson,

J. S.; Pursley, J. R.; Garverick, H. A.; Fricke, P. M.; Kesler, D. J.; Ottobre,

J. S.; Wiltbank, M. C. 2006. Treatment of cycling and noncycling lactating

dairy cows with progesterone during Ovsynch. Journal Dairy Science. 89:

2567-2578. DOI: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72333-5

42. Tschopp, J.

C.; Bó, G. A. 2022a. Success of artificial insemination based on expression of

estrus and the addition of GnRH to an oestradiol/progesterone-based protocol on

pregnancy rates in lactating dairy cows. Animal Reproduction Science. 238:

106954. DOI: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2022.106954

43. Tschopp, J.

C.; Macagno, A. J.; Mapletoft, R. J.; Menchaca, A.; Bó, G. A. 2022b. Effect of

the addition of GnRH and a second prostaglandin F2α treatment on pregnancy per

artificial insemination in lactating dairy cows submitted to an

estradiol/progesterone-based timed-AI protocol. Theriogenology. 188: 63-70.

DOI: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2022.05.019

44. Uslenghi,

G.; González Chavez, S.; Cabodevila, J.; Callejas, S. 2014. Effect of

oestradiol cypionate and amount of progesterone in the intravaginal device on

synchronization of estrus, ovulation and on pregnancy rate in beef cows treated

with FTAI based protocols. Animal Reproduction Science. 145: 1-7. DOI:

10.1016/j.anireprosci.2013.12.009

45. Vasconcelos,

J. L.; Sartori, R.; Oliveira, H. N.; Guenther, J. G.; Wiltbank, M. C. 2001.

Reduction in size of the ovulatory follicle reduces subsequent luteal size and

pegnancy rate. Theriogenology. 56: 307-314. DOI: 10.1016/S0093-691X(01)00565-9

46. Vasconcelos,

J. L. M.; Pereira, M. H. C.; Wiltbank, M. C.; Guida, T. G.; Lopes Jr, F. R.;

Sanches Jr, C. P.; Pereira Barbosa, L. F.; Costa Jr, W. M.; Kloster Munhoz, A.

2018. Evolution of fixed-time AI in dairy cattle in Brazil. Animal

Reproduction. 15(Suppl. 1): 940-951. DOI: 10.21451/1984-3143-AR2018-0020

47. Wiltbank, M.

C.; Pursley, R. J. 2014. The cow as an induced ovulator: Timed AI after

synchronization of ovulation. Theriogenology. 81: 170-185. DOI:

10.1016/j.theriogenology.2013.09.017

48. Yañez, D.;

Barbona, I.; López, J. C.; Moyano, J. C.; Quinteros, R.; Bernardi, S.; Marini,

P. R. 2016. Possible factors affecting pregnancy rate of cows in the amazon

ecuatorian. Proceedings, VI Peruvian Congress Animal Reproduction. p. 66. DOI:

10.18548/aspe/0004.12

Author

contributions

GAB:

Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing; PRM: Writing - review &

editing; JCLP: Supervision, Data curation, Methodology, Writing - original

draft. AM: writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of

interest

The authors

declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of

Funding and acknowledgments

This research

was supported by Fondo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (FONCYT PICT 2017-4550)

of Argentina and the Center of Postgraduate Research and Conservation of the

Amazon (CIPCA), Ecuador. We also thank our colleagues at the CIPCA for

technical assistance and Dr. Reuben J. Mapletoft from the University of

Saskatchewan for the critical review of the final versión of the manuscript.

A Data

Availability Statement

The data that

supports this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding

author.