Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 56(1). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2024.

Original article

Green

solvents for the recovery of phenolic compounds from strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa Duch) and apple (Malus

domestica) agro-industrial bio-wastes

Uso

de solventes verdes para la extracción de compuestos fenólicos a partir de

residuos agroindustriales de frutilla (Fragaria

x ananassa Duch) y manzana (Malus domestica)

1Universidad

Nacional del Litoral. Facultad de Ingeniería Química. Instituto de Tecnología

de Alimentos. Santiago del Estero 2829. 3000. Santa Fe. Argentina.

2Consejo

Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET). 3000. Santa Fe.

Argentina.

*ampiagen@fiq.unl.edu.ar

Abstract

We aimed to

study the obtention of valuable phenolic compounds from tissue by-products of

agro-industrial processing of apple (GS) and strawberry (RF) using green

solvents and Soxhlet extraction methodology. The effects of solvent type [water

(W); 80% ethanol, (EtOH)] and extraction ratio (1:10, 1:20, 1:30, and 1:40 p/v)

were determined on total phenolic content (TPC), antioxidant capacity (DPPH),

and the profile of phenolic compounds of the GS and RF extracts. The solvent

type and the extraction ratio significantly affected TPC and DPPH of GS and RF

extracts. Extraction with EtOH and 1:40 ratio produced the highest yields,

obtaining an RF extract with 15.8 g GAE/Kg (TPC) and 19 mmol TE/Kg (DPPH). The

tetra-galloyl glucose isomer and agrimoniin (0.8-0.4 g/Kg) were the main RF

phenolic compounds of the eight identified. GS extract, obtained with EtOH and

1:40 ratio, had 11.9 g GAE/Kg (TPC) and 20.5 mmol TE/Kg (DPPH), having

quercetin -3-o-glucuronide (0.43 g/Kg) the highest concentration among the

eight phenolic compounds identified. The results highlight the potential of

green solvents to obtain valuable compounds from low-cost raw materials, like

the high-antioxidant capacity phenolic compound extracts obtained herein.

Keywords: green

extraction, bioactive compounds, hydrolysable tannins, flavonols, natural

antioxidants

Resumen

El objetivo fue

estudiar la extracción de compuestos fenólicos con alto valor bioactivo, a

partir de subproductos del procesamiento de manzana (GS) y frutilla (RF),

utilizando solventes amigables con el medio ambiente y la extracción Soxhlet.

Se determinaron los efectos del tipo de solvente [agua (W); etanol 80% (EtOH)]

y la relación de extracción (1:10, 1:20, 1:30 y 1:40 p/v) sobre el contenido de

fenoles totales (TPC), capacidad antioxidante (DPPH) y perfil de compuestos

fenólicos. El tipo de solvente y la relación de extracción afectaron

significativamente el TPC y la DPPH. La extracción con EtOH a 1:40 produjo los

rendimientos más altos, obteniendo un extracto de RF con 15.8 g GAE/Kg (TPC) y

19 mmol TE/Kg (DPPH). El isómero de tetra galoil glucosa y agrimoniin (0,8-0.4

g/Kg) fueron los principales compuestos fenólicos de RF, entre los ocho

identificados. El extracto de GS, obtenido con EtOH a 1:40, tuvo 11,9 g GAE/Kg

(TPC) y 20,5 mmol TE/Kg (DPPH), con quercetin-3-o-glucuronido (0,43 g/Kg) como

el principal compuesto fenólico entre los ocho identificados. Los resultados

destacan el potencial de los solventes verdes para obtener compuestos fenólicos

de alta capacidad antioxidante potencialmente bioactivos a partir de materias

primas de bajo costo.

Palabras claves:

extracción

verde, compuestos bioactivos, taninos hidrolizables, flavonoles, antioxidantes

naturales

Originales:

Recepción: 25/10/2023 - Aceptación: 26/12/2023

Introduction

One-third of

fruit and vegetable production is wasted or lost in the production chain,

producing avoidable and non-avoidable waste (3, 31). The former

includes the losses generated by wrong handling during postharvest, processing,

transport, storage, and distribution, and the non-avoidable waste is that part

of the vegetable or fruit that must be eliminated for processing and sale

(peels, seeds, core, and inedible parts). Therefore, the appropriate disposal

of this waste is essential to reduce the environmental and economic impact of

agro-industrial activity. The circular economy proposes different solutions to

prevent this waste plant tissue from ending up in city landfills (35). Although the

composition of fruit and vegetable by-products includes vitamins, minerals, and

carbohydrates (27), as well as

different bioactive compounds like phenolic compounds, these residual plant tissues

are mainly used as ingredients in animal feed or as a source of energy for

boilers. Waste fruit and vegetable tissues are sources of phenolic compounds

with significant health benefits for consumers and antioxidant properties (24,

33).

Phenolic compounds are synthesised in the plant´s secondary metabolism during

the normal development of plants. Their chemical structure has at least one

aromatic ring with one or more hydroxyl groups, showing different biological

activities according to their carbon bridges and hydroxyl substitution.

The production,

consumption and industrial processing of apples and strawberries continue to

increase worldwide, and so do the wasted tissues associated (12). Non-edible or

non-processable fruit parts may have better composition and bioactivity than

edible tissues (5, 34). The main

phenolic compounds of strawberries are ellagitannins, phenolic acids and

flavonoids like anthocyanins (32), and the

principal apple phenolic compounds are catechins and proanthocyanidins (17), depending on

the cultivar, the area, and the type of production of these crops. The

extraction method of these compounds significantly impacts the extraction

yields and their bioactive potential. Considering the structural diversity of

the phenolic compounds, no single extraction system could produce the total

recovery of these metabolites of interest from all vegetable tissues.

The solid-liquid

extraction is commonly used to obtain phenolic compounds, and the success of

this process depends on the plant matrix, kind of solvent, temperature, pH, and

extraction technology. Polar protic solvents, like ethanol and methanol, can

donate hydrogen bonds (33). Otherwise,

polar aprotic solvents (acetone and ethyl acetate) have dipoles but do not

possess hydrogen atoms bonded with a high electronegativity atom that can be

donated in a hydrogen bond. Finally, apolar solvents (hexane and petroleum

ether) have bonds between atoms with similar electronegativities (33). The

extraction technique also affects phenolic compound yield. The Soxhlet

extraction technique is widely used for obtaining secondary metabolites from

different plant tissues, being a reference method for comparing the performance

of other extraction techniques. The Soxhlet extraction has good extraction

yields without using large quantities of solvent, with a total extraction time

of 1-6h, including multiple extraction cycles. This technique commonly employs

flammable, hazardous, and toxic organic solvents. The low production cost of

ethanol (by fermentation from renewable sources), low energy requirements for

final disposal and moderate chronic toxicity make it a sustainable option to

replace traditional solvents, along with water, considered the greenest

solvent. Water application is generally limited to low-polarity metabolites;

nevertheless, it is possible to broaden the solubilisation spectrum of wáter

with suitable parameters (8). Therefore,

green extraction with safe and non-toxic solvents, like water, ethanol, and

binary ethanol-water mixtures, must be studied. Both solvents are considered

safe and acceptable for use in the food industry by regulatory agencies (FDA).

The ethanol-aqueous solutions for polyphenol extraction from plant tissues have

better yields due to their azeotropic behaviour (1). Additionally,

safe solvents in Soxhlet extraction could also yield higher amounts of phenolic

compounds from some agro-industrial waste (7, 8, 26).

Complementary

treatments with phenolic compounds that strengthen the immune system or their

use as antioxidant agents would promote obtaining these phenolic compounds of

interest at a low cost, facilitating the accessibility to a larger population

and valuing the wasted agro-industrial tissues using green technologies.

Therefore, this work aims to study the extraction of the phenolic compounds

from strawberry by-products and ‘Granny Smith’ apple peel, characterise the

obtained extracts using the Soxhlet method, evaluate the impact of two green

solvents (water and ethanol 80%), and different solid-liquid ratios on the

total phenolic content, phenolic profile, and in-vitro antioxidant activity of

the extracts. have bonds between atoms with similar electronegativities (33). The

extraction technique also affects phenolic compound yield. The Soxhlet

extraction technique is widely used for obtaining secondary metabolites from

different plant tissues, being a reference method for comparing the performance

of other extraction techniques. The Soxhlet extraction has good extraction

yields without using large quantities of solvent, with a total extraction time

of 1-6h, including multiple extraction cycles. This technique commonly employs

flammable, hazardous, and toxic organic solvents. The low production cost of

ethanol (by fermentation from renewable sources), low energy requirements for

final disposal and moderate chronic toxicity make it a sustainable option to

replace traditional solvents, along with water, considered the greenest

solvent. Water application is generally limited to low-polarity metabolites;

nevertheless, it is possible to broaden the solubilisation spectrum of water

with suitable parameters (8). Therefore,

green extraction with safe and non-toxic solvents, like water, ethanol, and

binary ethanol-water mixtures, must be studied. Both solvents are considered

safe and acceptable for use in the food industry by regulatory agencies (FDA).

The ethanol-aqueous solutions for polyphenol extraction from plant tissues have

better yields due to their azeotropic behaviour (1). Additionally,

safe solvents in Soxhlet extraction could also yield higher amounts of phenolic

compounds from some agro-industrial waste (7, 8, 26).

Complementary

treatments with phenolic compounds that strengthen the immune system or their

use as antioxidant agents would promote obtaining these phenolic compounds of

interest at a low cost, facilitating the accessibility to a larger population

and valuing the wasted agro-industrial tissues using green technologies.

Therefore, this work aims to study the extraction of the phenolic compounds

from strawberry by-products and ‘Granny Smith’ apple peel, characterise the

obtained extracts using the Soxhlet method, evaluate the impact of two green

solvents (water and ethanol 80%), and different solid-liquid ratios on the

total phenolic content, phenolic profile, and in-vitro antioxidant activity of

the extracts.

Materials

and methods

Plant

material and Experimental design

The by-products

of strawberry (RF) (Fragaria x ananassa Duch) cv ‘Festival’, consisting

of sepals and stems, with non-processable parts of the fruit (part of the fruit

closest to the sepal and peduncle), came from a single field (Coronda, Santa

Fe, Argentina) during postharvest preparation for industrial processing.

‘Granny Smith’ apple peel (GS, 1 mm thickness) was obtained from the minimal

processing of apples, according to Rodríguez-Arzuaga

and Piagentini (2018).

The RF and GS samples (89.2% and 80.4% moisture content, respectively) were

weighed, packed in 40 μm polyethylene bags, and stored at -20°C until

processing. Before extraction assays, both samples were ground to a particle

size <1 mm.

The effect of

the extraction solvent (S) and the solid-liquid ratio (R) in the phenolic compound

extraction of each vegetable tissue (RF and GS) was studied through a factorial

experimental design. The two experimental variables of each factorial design

were S and R, with two [S: water (W) and ethanol 80% (EtOH)] and four levels

[R: 1:10, 1:20, 1:30 and 1:40 w/v], respectively. The total phenolic content

(TPC), phenolic compound profile, and antioxidant capacity (DPPH) were

determined on each extract of RF and GS. The extraction times were four hours

for EtOH extractions and eight hours for W extractions (extraction times

determined in preliminary assays). The extracts were cooled (20°C), filtered,

and stored at -20°C for further analysis. Each phenolic compound extraction

assay was performed in triplicate.

Total

phenolic content (TPC)

Each extract TPC

was determined in triplicate by the Folin-Ciocalteu method (34). Gallic acid

(Sigma-Aldrich, San Luis, Missouri, USA) was used as the standard reagent to

perform the calibration curve, measuring the absorbance of the reaction at 760

nm in a spectrophotometer (Genesys 10s UV-Vis, Thermo Scientific™, Waltham,

Massachusetts, USA). The concentration of TPC was reported as g of gallic acid

equivalent (GAE) per kilogram of RF or GS (g GAE/Kg).

Phenolic

compound profile

The phenolic

compound profile of the extracts was performed with an LC-20AT HPLC with a

photodiode array detector (PAD), with the software Lab Solutions for data

processing and control (Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan). The separation was

performed with a hybrid reverse phase column C18 Gemini 5μ 110Å of 250×4.6 mm,

attached to a guard column (Phenomenex Inc, CA, USA). The analysis was

performed according to Villamil-Galindo et al. (2021) for RF and Villamil-Galindo

and Piagentini (2022a)

for GS. The quantification of the identified compounds was performed using the

following external standards (Sigma-Aldrich Inc. St. Louis, Missouri, USA):

Ellagic acid (EA), Kaempferol-3-O-glucoside (K3G), Quercetin-3-O-glucoside

(Q3G), Chlorogenic acid (ACl), Procyanidin B2 (PACB2), (-) Epicatechin (EPQN),

(+) Catechin (CQN), Floretin (FLN), Gallic acid (GA), Coumaric acid (CUA), and

Ferulic acid (FRA). The results were expressed in g per Kg of tissue

by-product.

Antioxidant

capacity (DPPH)

The extract DPPH

was determined using the 2.2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical (DPPH*)

scavenging assay, performed by triplicate (34). A volume (200

μL) of the DPPH* methanolic solution (0.08 mM) reacts with 25 μL of extract or

reference reagent 2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic

acid (Trolox, Sigma-Aldrich), and the absorbance was measured at 515 nm in a

microplate reader (Asus UVM 340, Cambridge, England) after 2 h. The results

were expressed as mmol Trolox equivalents/Kg of tissue by-product (mmol TE/Kg).

Statistical

analysis

All assays were

carried out in triplicates, and data were presented as the mean ± standard

deviation (SD). The effect of the solid-liquid ratio and the extraction solvent

on the total phenolic content, phenolic compound profile and antioxidant

capacity of RS and GS extracts were determined by the analysis of variance

(ANOVA). Tukey´s test (5% significance level) was used to determine the

significant differences among treatment means. Besides, the correlation between

the individually identified phenolic compounds and the antioxidant capacity

determined in each extract was determined using Pearson’s correlation test. The

statistical analysis was performed with STATGRAPHICS Centurion XV software

(StatPoint Technologies Inc., Warrenton, VA, USA).

Results

and discussion

Phenolic

compounds recovery from strawberry agro-industrial by-products (RF)

Both Soxhlet

extraction parameters [solid-liquid ratio (R) and type of solvent (S)] affected

(p<0.001) the yields of total phenolic content (TPC), the phenolic

compounds profile, and the antioxidant capacity (DPPH) of the strawberry

agro-industrial by-products extracts. The interaction term between R and S was

also significant (p<0.001), meaning that R affected in a different

way TPC, DPPH, and the phenolic compounds profile of the extracts depending on

the type of solvent used.

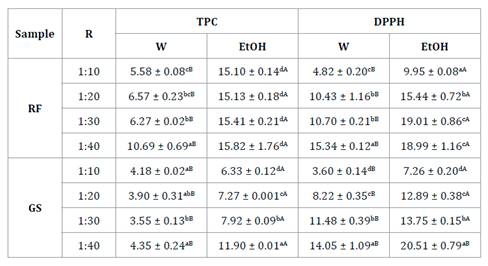

The increase of

R values improved the TPC yields of RF Soxhlet extraction with wáter (W), with

the highest yield (10.69 g GAE/Kg) obtained at R 1:40, up to 48% higher than those

obtained at lower R values (table 1).

Table

1. Total phenolic content (TPC) and

antioxidant capacity (DPPH) of the extracts from strawberry by-products (RF)

and ‘Granny Smith’ apple peel (GS).

Tabla 1. Contenido

de fenoles totales (TPC) y capacidad antioxidante (DPPH) de los extractos de

sub-productos de frutilla (RF) y cáscara de manzana ‘Granny Smith’ (GS).

Mean ± standard deviation. R: Solid-liquid ratio. W:

water; EtOH: 80% ethanol. Different capital letters and lowercase letters

indicate significant differences (p<0.05) by Tukey’s test, between solvent

and among different solid-liquid ratios, respectively.

Promedio ± desviación estándard. R: relación

sólido-líquido. W: agua; EtOH: 80% etanol. Letras mayúscula y minúsculas

indican diferencias significativas (p<0,05) por el test de Tukey, entre

solvente y entre diferentes relaciones sólido-líquido, respectivamente.

The

concentration gradient between the solute and solvent was the driving force for

the diffusion process. Therefore, better extraction yields were obtained with

the highest R-value (1:40). Therefore, strawberry by-products have great

potential as a source of bioactive compounds obtained with water.

The RF Soxhlet

extraction with EtOH significantly increased the recovery of TPC as compared

with W by 47-170% (table 1). Contrary to W

extractions, R did not affect the TPC yields of the EtOH extracts (mean value

15.37 g GAE/Kg) (table 1). The phenolic compounds of RF could

present preferential solvation when using water-ethanol. The compounds would

show hydrophobic hydration with the few polar groups they could have in their

structure, and a large amount of (-OH) groups would allow more interaction with

water (6). Therefore,

this phenomenon would produce more effect than the increase in the extraction

ratio. However, the use of EtOH on the Soxhlet extraction system significantly

increased the TPC yields compared to RF water extracts, improving extraction

yields by up to 170% (table 1). Therefore,

the lower the extraction ratio, the smaller the solvent needed, and the lower

the production costs of the extracts.

Furthermore,

these results confirm that binary ethanol-water mixtures are suitable

bio-solvents for obtaining phenolic compounds due to their polar protic

properties. The yields obtained for RF with EtOH using Soxhlet extraction were

higher than those reported for pandan leaves (6.6 g GAE/Kg), mango by-products

(4.5-6.6 g GAE/Kg), asparagus (2.8-3.7 g GAE/Kg), cauliflower (1.1-1.8 g

GAE/Kg), and bergamot lemon (4-10 g GAE/Kg) (4, 14, 15, 27).

Regarding the

antioxidant capacity of RF water extracts, they were significantly affected by

R-value, comparable to TPC. The highest DPPH value was obtained for the 1:40

ratio (15.3 mmol TE/Kg), being up to 69% higher than that obtained at R 1:10.

Otherwise, like with the content of phenolic compounds, EtOH improved the

antioxidant capacity of the RF extracts obtained compared with W extracts. The

EtOH RF extracts with the highest DPPH values (18.9-19.0 mmol TE/Kg) were those

obtained with R 1:40 and 1:30 (p>0.05), respectively. The phenolic compounds

are excellent antioxidants of natural origin due to their reducing- capacity,

shown by the highly significant correlation between the TPC and the antioxidant

capacity of the RF extracts.

Eight major phenolic

compounds were identified for the strawberry agro-industrial waste tissue (RF),

belonging to three main phenolic compound classes: hydrolysable tannins,

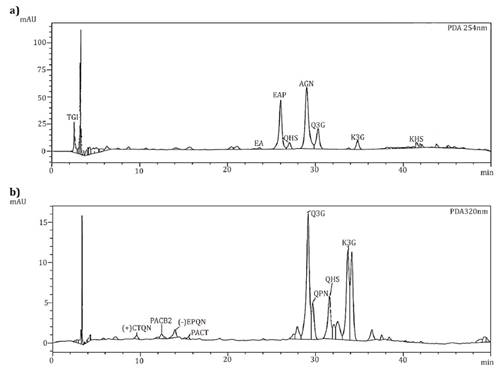

ellagic acid derivatives, and flavonols (figure 1a and figure

2).

TGI:

Tetragalloyglucose isomer, EAP: Ellagic acid pentoxide, AGN:

Dimer of galloyl-bis-HHDPglucose (agrimoniin isomer), EA: Ellagic acid, Q3G:

Quercetin- 3-O-glucuronide, QHS: Quercetin Hexoxide, K3G:

Kaempferol-3- O-glucuronide. (+) CTQN: Catechin, PACB2:

Procyanidin B2, (-) EPQN: Epicatechin, PACT: Procyanidin

tetramer, QPN: Quercetin pentoxide.

TGI:

Tetragalloyglucosa isomero, EAP: pentoxidode ácido Ellagico, AGN:

Dimero de galloylbis- HHDP-glucosa (agrimoniin isomero), EA: ácido

Ellagico, Q3G: Quercetin-3- O-glucuronido, QHS: Quercetin

Hexoxido, K3G: Kaempferol-3-Oglucuronido. (+) CTQN:

Catequina, PACB2: Procianidina B2, (-) EPQN: Epicatequina, PACT:

Procianidin tetramero, QPN: Quercetina pentoxido.

Figure 1. Typical

HPLC-UV chromatogram obtained of (a) strawberry by-products at 254 nm and (b)

‘Granny Smith’ apple peel at 320 nm.

Figura 1. Cromatograma

típico HPLC-UV obtenido para (a) sub-productos de frutillas a 254 nm y (b)

cáscara de manzanas ‘Granny Smith’ a 320 nm.

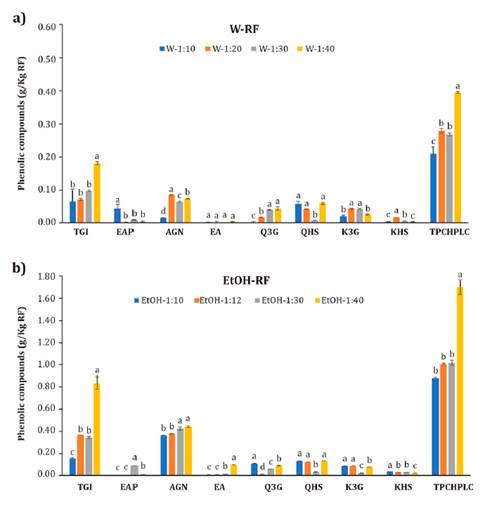

TGI:

Tetragalloyglucose isomer, EAP: Ellagic acid pentoxide, AGN:

Dimer of galloyl-bis-HHDPglucose (agrimoniin isomer), EA: Ellagic acid, Q3G:

Quercetin- 3-O-glucuronide, QHS: Quercetin Hexoxide, K3G:

Kaempferol- 3-O-glucuronide, TPCHPLC: Total phenolic compounds

analyzed by HPLC. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences

(p<0.05) by Tukey´s test, between different solidliquid ratios.

TGI:

Tetragalloyglucosa isomero, EAP: pentoxido de ácido Ellagico, AGN:

Dimero de galloylbis- HHDP-glucosa (agrimoniin isomero), EA: ácido

Ellagico, Q3G: Quercetin-3- O-glucuronido, QHS: Quercetin

Hexoxido, K3G: Kaempferol-3-Oglucuronido, TPCHPLC:

Compuestos fenólicos totales analizados por HPLC. Diferentes letras minúsculas

indican diferencias significativas (p<0,05) por el test de Tukey, entre

diferentes relaciones sólido-líquido.

Figure 2. Phenolic

compounds from strawberry by‑products (RF) extracted with a) wáter (W) and b)

80% ethanol (EtOH).

Figura 2. Compuestos

fenólicos de los sub-productos de frutilla extraídos con a) agua (W) and b) 80%

etanol (EtOH).

Tetragalloyl-glucose

isomer (TGI) and galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose dimer (agrimoniin) (AGN) were

identified among the hydrolysable tannins; ellagic acid pentoxide (EAP) and

free ellagic acid (EA) among the ellagic acid derivatives; and finally, the

flavonols were represented by quercetin-3-O-glucuronide (Q3G), quercetin

hexoxide (QHS), kaempferol-3-O-glucuronide (K3G), and kaempferol hexoxide

(KHS).

For the water

extracts at R 1:10, hydrolysable tannins represented 38.5% of the total

phenolic compounds, similar to flavonols with 39.9%, followed by ellagic acid

derivatives with 21.6% (figure 2a). However, as

the extraction ratio increased, hydrolysable tannins represented 64% of the

total phenolic compounds in the extracts obtained with R 1:40, showing that the

increase in the concentration gradient in the extraction solvent (W) allowed

greater recovery of hydrolysable tannins (33).

The highest

concentration of tetragalloylglucose isomer (TGI) in W extracts was obtained at

R 1:40 (0.18 g/Kg); for the other R-values, the TGI concentration was similar

(0.07-0.1 g/Kg) (figure 2a). EtOH extraction significantly

improved the TGI yields for all extraction ratios, with the maximum

concentration at R 1:40 (0.83 g/Kg). The Ellagic acid pentoxide (EAP) had the

highest concentration, 0.088 g/Kg (p<0.05), in the EtOH extracts (figure

2).

EAP concentrations were higher than those reported for the stem of Sanguisorba

Officinalis L (Rosaceae family) (0.038 g/Kg) (20). Agrimoniin

(AGN) is a compound derived from hexahydroxydiphenic acid (HHDP), considered a

taxonomic marker of the Rosaceae, with great importance in the nutraceutical

industry due to its bioactive properties (30). The AGN yield

obtained with water was about 0.064-0.084 g/kg for the higher R values. The AGN

yields were significantly improved for all R-values (p<0.05) when EtOH was

used, with a maximum concentration of 0.44 g/Kg at R 1:40 (figure 2). This AGN

concentration was higher than the reported for whole strawberry fruit extracts

(0.12 g/Kg) obtained with 70% methanol (25), showing this

residual tissue as a valuable source of AGN. The antioxidant properties of

hydrolysable tannins have been reported in-vitro and in-vivo (16). Simirgiotis

et al. (2010)

reported that cyanidin glucosides and ellagic acid were the compounds with the

highest participation in the antioxidant activity in the edible part of

strawberries. For RF, the hydrolysable tannins TGI and AGN had a significant

correlation (p<0.01) with the DPPH* antioxidant capacity. These compounds

have polyhydric alcohol in the centre, and their hydroxyl groups could be

partially esterified with ellagic acid or HHDP, having the capacity to yield

electrons and thus neutralise the free radicals present (14). The ellagic

acid (EA) concentrations were lower in W extracts for any extraction ratio

(p>0.05). Like AGN, EtOH improved the extraction of EA, with a maximum

concentration of 0.10 g/Kg R 1:40 (figure 2). The

consumption of ellagic acid derivatives was associated with numerous health

benefits since, in-vivo conditions, different types of urolithins were

metabolised by the microbiota, which had powerful antiproliferative and cancer

cell apoptosis-inducing activities (21).

The flavonol

Quercetin-3-o-glucuronide (Q3G) concentrations in RF water extracts were

0.002-0.04 g/Kg, obtaining the higher at R 1:40 and 1:30 (p>0.05).

Nevertheless, using 80% ethanol significantly increased Q3G yields up to 0.11

g/Kg (figure

2),

similar to chokeberry extracts (11). QHS

concentrations obtained with EtOH (0.12-0.13 g/Kg) were higher than those

obtained with W (0.04-0.05 g/Kg). Kaempferol is one of the most common

flavonols in different botanical species. In the cell vacuoles, Kaempferol

tends to glycosidate with some carbohydrates to have more stability in the pH

of the medium (28). The highest

kaempferol-3-o-glucuronide (K3G) concentration obtained with water was 0.043

g/Kg. EtOH improved the K3G extraction yields by about 50% (figure 2). K3G values in

RF were close to those reported for green tea (60% methanol), a popular

antioxidant infusion (19). Finally, the

Kamepferol Hexoxide (KHS) yield increased by up to 91% in EtOH extractions

compared to water extracts (figure 2).

Therefore, the

agro-industrial strawberry by-product showed a large variability of phenolic

compounds of interest. The highest recovery of total phenolic compounds

(TPCHPLC) with W was achieved with R 1:40 (0.40 g/Kg). As expected,

the EtOH increased TPCHPLC up to 425%, obtaining the highest concentration also

at R 1:40 (figure

2).

Similar to the results of TPC and DPPH, the extractions with the ethanol-water

binary mixture (80:20) had the highest recovery of phenolic compounds with high

antioxidant capacity. The máximum TPCHPLC content (1.70 g/Kg) obtained for RF

EtOH extracts was comparable to that reported for strawberry plant leaves

(1.95-2.07 g/Kg) obtained with methanol-formic acid (99:1) (30). The phenolic

compounds of RF have an excellent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and

anticarcinogenic potential for colorectal cancer (34, 36). Therefore,

the high concentration of hydrolysable tannins and ellagic acid derivatives in

RF enables the promotion of this kind of agro-industrial by-products as a

low-cost source of healthy compounds.

Phenolic

compounds recovery from ‘Granny Smith’ apple peel (GS).

The solid-liquid

ratio (R) and the type of solvent (S) affected (p<0.001) the content of

phenolic compounds and the antioxidant capacity of GS extracts. The interaction

term between R and S was also significant (p<0.001) for TPC, DPPH, and

phenolic compounds profile.

The use of EtOH

improved the TPC recovery from GS, like RF (table 1). The TPC of GS

EtOH extracts increased as R increased, obtaining the highest yield (11.9 g

GAE/Kg) for R 1:40. Castro-López et al. (2017) reported that

R-values higher than 1:20 increased the recovery of phenolic compounds. Binary

alcohol-water mixtures offer an eco-friendly solvent system for obtaining

phenolic compounds from different wasted plant matrices than those using pure

ethanol or other organic solvents. The water and ethanol mixture act

synergistically and could provide a suitable polarity range for extracting

phenolic compounds (medium-high polarity). The former is fundamental as a

swelling agent of the plant matrix, allowing the lower viscosity ethanol to

diffuse through the material and break the non-covalent interactions between

the solute and the matrix, facilitating the preferential solvation sphere

transferring the analyte to the dissolution medium (33).

Phenolic

compounds are the plant-secondary metabolites with the highest reported

antioxidant activity. Each compound antioxidant capacity differs due to its

oxidation-reduction reactions, phenyl ring structure resonance, and hydroxyl

group substitution pattern (32). The

antioxidant capacity of GS extracts at R 1:40 is 47% higher in EtOH extract

than in W extract. The DPPH values obtained were comparable to those reported

for other plant materials by Soxhlet extraction (sugar beet molasses, rapeseed,

and flowers of Jatropha integerrima) (10, 13). The use of

EtOH enhanced the antioxidant capacity of GS extracts as R increased (table

1),

comparable to TPC, and therefore, showing a strong correlation between TPC and

DPPH (p<0.01).

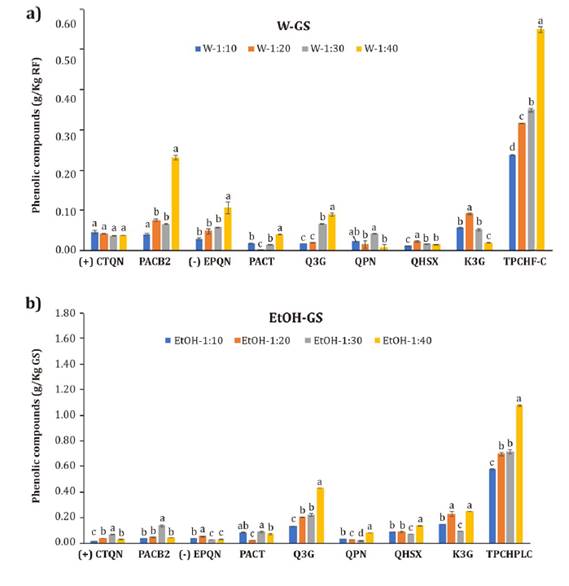

The two main

classes of phenolic compounds identified and quantified in ‘Granny Smith’ apple

peel (GS) were the flavan-3-ols with (+) catechin [(+) CTQN], Procyanidin B2

(PACB2), (-) epicatechin [(-) EPQN], and Procyanidin tetramer (PACT); and the

flavonols with the Quercetin-3-o-glucuronide (Q3G), Quercetin pentoxide (QPN),

Quercetin Hexoxide (QHS), and Kaempferol-3-o-glucuronide (K3G) (figure

1b

and figure

3).

(+)CTQN:

Catechin, PACB2: Procyanidin B2, (-)EPQN:

Epicatechin, PACT: Procyanidin tetramer, Q3G: Quercetin- 3-O-glucuronide,

QPN: Quercetin pentoxide, QHS: Quercetin Hexoxide, K3G:

Kaempferol- 3-O-glucuronide, TPCHPLC: Total phenolic compounds

analyzed by HPLC. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences

(p<0.05) by Tukey´s test, between different solid-liquid ratios.

(+)CTQN:

Catequina, PACB2: Procianidina B2, (-)EPQN:

Epicatequina, PACT: Procianidina tetramero, Q3G: Quercetina-3- O-glucuronido,

QPN: Quercetina pentoxido, QHS: Quercetina Hexoxido, K3G:

Kaempferol-3-Oglucuronido, TPCHPLC: Compuestos fenólicos totales

analizados por HPLC. Diferentes letras minúsculas indican diferencias

significativas (p<0,05) por el test de Tukey, entre diferentes relaciones

sólidolíquido.

Figure 3. Phenolic

compounds from ‘Granny Smith’ apple peel (GS) extracted with a) water (W) and

b) 80% ethanol (EtOH).

Figura 3. Compuestos

fenólicos de cáscara de manzana compounds from ‘Granny Smith’ (GS) extraidos

con a) agua (W) and b) 80% etanol (EtOH).

For the GS W

extracts, the flavan-3-ols and flavanols represented each 50 % of the total

phenolic compounds (R 1:10, 1:20 and 1:30), increasing the flavan-3-ols

proportion with R 1:40 up to 76 % of the total of the quantified compounds,

showing the affinity of this class of phenolic compounds for a polar solvent

like water (figure 3a). Nevertheless, flavonols accounted for

more than 50% of the total phenolic compounds in all the EtOH extractions, with

a maximum of 84% in the extracts with R 1:40 (figure 3b).

R did not affect

(p>0.05) the (+)CTQN extraction yield with water.

EtOH extractions increased (+)CTQN yields up to 0.066

g/kg, 77% higher than W extracts (figure 3). The (+)CTQN yields obtained were lower than those reported by Almeida

et al. (2017)

for ‘Granny Smith’ apple peel extracted with 100% acetone (0.17 g/Kg). PACB2

(epicatechin-epicatechin dimer) is the most common proanthocyanidin determined

in high concentrations in fruits like peaches, apples, and plums. The PACB2

content in W extracts increased with R; it was at least 71% higher for R 1:40

than for the other extraction ratios. However, ethanol did not improve the

PACB2 extraction yields. Procyanidin B2 in a liquid medium from 90°C onwards

starts a degradation process by oxidation and epimerisation, lowering the

procyanidin B2 recovery. The highest concentration of EPQN, reported as the

main phenolic compound in apples (23), was achieved

with W and R 1:40 (0.1 g/Kg), being higher than that reported for apple pomace

extracts (0.02 g/Kg) (20). The highest

PACT concentration in W extracts was 0.04 g/Kg, obtained at R 1:40. The EtOH

improved PACT yields (p<0.05) for all R values (figure 3). Procyanidins

are oligomers composed of catechin and epicatechin; their structure and high

molecular weight give them different bioactive and functional properties for

the food industry.

Q3G extraction

yields with W were affected by R, obtaining the highest one at R 1:40, 82%

higher than the yields obtained at lower R values. Nevertheless, the EtOH

improved Q3G extraction yields, as expected for a medium polarity compound. The

highest Q3G yield with EtOH (0.43 g/Kg) was obtained at R 1:40, 50% higher than

those obtained at lower R values (figure 3). Moreover, Q3G

was the GS individual compound with the highest correlation with the

antioxidant capacity, mainly for its structure and hydroxyl groups that allowed

the donation of electrons, neutralising the free radicals present in the medium

(32). Contrarily, RF flavonols did not show

a highly significant correlation with the antioxidant capacity determined by

DPPH. Consequently, the bioactive potential did not depend only on the

bioactive compound concentration but also on the interaction with the food

matrix. The values obtained with EtOH were similar and even higher than those

reported for ‘Granny Smith’ apple peel acetone extracts (0.18-0.4 g/Kg) (2).

The highest

concentration of QPN, the other quercetin glucoside derivative, was obtained

with EtOH at R 1:40 (0.08 g/Kg). The yields of QHS in EtOH extracts were higher

than in W, obtaining the highest concentration at R 1:40 (0.14 g/Kg). According

to previous reports, quercetin and its glycosides have a low bioavailability

(16-25%) due to their low water solubility and crystalline structure at body

temperatures (16). Like the

other flavonols, EtOH enhanced the recovery of K3G, with the highest

concentration (0.25 g/Kg) at R 1:40 (figure 3).

Considering the

sum of the compounds identified and quantified, the TPCHPLC obtained for W

extracts increased with R, determining the highest concentration in W at R 1:40

(0.55 g/Kg) (figure 3a). Higher TPCHPLC values were obtained

with EtOH and higher R values. TPCHPLC extracted with EtOH 1:40 (1.07 g/Kg) was

higher than that reported for the apple pulp (17), showing the

bioactive potential of apple peel. The GS TPCHPLC highly correlates with

antioxidant activity (R2 0.87), mainly due to flavonols. These results

encourage the integral use of the apple peel as a source of valuable compounds,

focusing on green solvents use with low environmental impact and cost (35).

Conclusions

There is a

growing demand for nutraceutical products of vegetable origin, as their

frequent consumption has been associated with a decreasing risk of having

chronic non-transmissible diseases. The market for nutraceutical compounds is

booming, and the extraction of bioactive compounds using clean solvents from

agro-industrial waste tissues, like the strawberry by-products and apple peel,

presents an opportunity to reduce costs and the environmental impact. The

conventional Soxhlet extraction technique has good yields, low complexity, and

high efficiency, allowing optimal use of natural resources, especially those

that are rejected for industrial processing, like the waste tissue produced

during the postharvest trimming of the strawberry (about 7-20% of the fruit

intended for industrial processing) and Granny Smith apple peel (about 12% of

the fruit intended for minimal processing).

This study

demonstrates that waste vegetable tissues can be transformed into valuable

phenolic compounds with antioxidant properties using eco-friendly solvents such

as water and ethanol. The extracts with the highest content of phenolic

compounds and antioxidant capacity were obtained for Soxhlet extraction with

80% ethanol and 1:40 extraction ratio for both the strawberry by-products (15.8

g GAE/Kg and 19 mmol TE/Kg) and the ‘Granny Smith’ apple peel (11.9 g GAE/Kg

and 20.5 mmol TE/ Kg). Additionally, eight main phenolic compounds were

identified and quantified in both waste tissues. The hydrolysable tannins, like

Tetragalloyglucose isomer (TGI: 0.83 g/Kg) and Dimer of

galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose (agrimoniin isomer, AGN: 0.44 g/Kg), were the main phenolic

compounds extracted from RF, while flavonols accounted for 83.7% of the total

extracted phenolic compounds from GS, obtaining for Quercetin-3-O-glucuronide

the highest yield (Q3G: 0.43 g/Kg).

These results

demonstrated the importance of by-products as low-cost sources of bioactive

compounds with high nutraceutical potential through a circular process approach

in the fruit and vegetable industry. Currently, these bio-wastes are disposed

of in landfills without any use. The information obtained in this study

provides a pathway towards the integral use of strawberry and apple

by-products. The challenge is to continue studying the development of a

procedure for obtaining bioactive compounds from strawberry by-products and

‘Granny Smith’ apple peel with higher yields, shorter extraction times and

lower energy consumption, using more sustainable and efficient technologies

stimulating an integral use of these by-products.

Acknowledgments

The authors

acknowledge the Universidad Nacional del Litoral and the Agencia Santafesina de

Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (ASaCTei) (Santa Fe-Argentina) for financial

support through Projects CAI+D 2020 and PEICID-2022-177; the support of CONICET

(Argentina) from a doctoral grant; and María del Huerto Sordo for providing strawberry

by-products.

1. Alara, O.;

Abdurahman, N.; Ukaegbu, C. 2018. Soxhlet extraction of phenolic compounds from

Vernonia cinerea leaves and its antioxidant activity. Journal of Applied

Research on Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. 11: 12-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmap.2018.07.003

2. Almeida, D.

P. F.; Gião, M. S., Pintado, M.; Gomes, M. H. 2017. Bioactive phytochemicals in

Apple cultivars from the Portuguese protected geographical indication “Maçã de

Alcobaça”: Basis for market segmentation. International Journal of Food

Properties. 20(10): 2206-2214. https://doi.org/10.1080/10942912.2016.1233431

3. Bigaran

Aliotte, J. T.; Ramos de Oliveira, A. L. 2022. Multicriteria decision analysis

for fruits and vegetables routes based on the food miles concept. Revista de la

Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza.

Argentina. 54(1): 97-108. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.069

4.

Blancas-Benitez, F. J.; Mercado-Mercado, G.; Quirós-Sauceda, A. E.;

Montalvo-González, E.; González Aguilar, G. A.; Sáyago-Ayerdi, S. G. 2015.

Bioaccessibility of polyphenols associated with dietary fiber and in vitro kinetics

release of polyphenols in Mexican “Ataulfo” mango (Mangifera indica L.)

by-products. Food and Function. 6(3): 859-868.

https://doi.org/10.1039/c4fo00982g

5. Boiteux, J.;

Fernández, M. de los Á.; Espino, M.; Silva, M. F.; Pizzuolo, P. H.; Lucero, G.

S. 2023. In vitro and in vivo efficacy of Larrea divaricata extract

for the management of Phytophthora palmivora in olive trees. Revista de

la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza.

Argentina. 55(2): 97-107. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.112

6. Bosch, E.;

Rosés, M. 1992. Relationship between ET polarity and composition in binary

solvent mixtures. Journal of the Chemical Society, Faraday Transactions.

88(24): 3541-3546. https://doi.org/10.1039/FT9928803541

7. Bucić-Kojić,

A.; Planinić, M.; Tomas, S.; Bilić, M.; Velić, D. 2007. Study of solid-liquid

extraction kinetics of total polyphenols from grape seeds. Journal of Food

Engineering. 81(1): 236-242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2006.10.027

8. Carciochi, R.

A.; Manrique, G. D.; Dimitrov, K. 2015. Optimization of antioxidant phenolic

compounds extraction from quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) seeds. Journal of

Food Science and Technology. 52(7): 4396-4404.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-014-1514-4

9. Castro-López,

C.; Ventura-Sobrevilla, J. M.; González-Hernández, M. D.; Rojas, R.; Ascacio-Valdés,

J. A.; Aguilar, C. N.; Martínez-Ávila, G. C. G. 2017. Impact of extraction

techniques on antioxidant capacities and phytochemical composition of

polyphenol-rich extracts. Food Chemistry. 237: 1139-1148.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.06.032

10. Chen, M.;

Zhao, Y.; Yu, S. 2015. Optimisation of ultrasonic-assisted extraction of

phenolic compounds, antioxidants, and anthocyanins from sugar beet molasses.

Food Chemistry. 172: 543-550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.09.110

11. Ćujić, N.;

Šavikin, K.; Janković, T.; Pljevljakušić, D.; Zdunić, G.; Ibrić, S. 2016.

Optimization of polyphenols extraction from dried chokeberry using maceration

as traditional technique. Food Chemistry. 194: 135-142.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.08.008

12. del Brio,

D.; Tassile, V.; Bramardi, S. J.; Fernández, D. E.; Reeb, P. D. 2023. Apple (Malus

domestica) and pear (Pyrus communis) yield prediction after tree

image analysis. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad

Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 55(2): 1-11. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.104

13. Feng, X.;

Chenyi, L.; Jia, X.; Guo, Y.; Lei, N.; Hackman, R.; Chen, L.; Zhou, G. H. 2016.

Influence of sodium nitrite on protein oxidation and nitrosation of sausages

subjected to processing and storage. Meat Science. 116.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2016.01.017

14. Ghasemzadeh,

A.; Jaafar, H. Z. E. 2014. Optimization of reflux conditions for total

flavonoid and total phenolic extraction and enhanced antioxidant capacity in

Pandan (Pandanus amaryllifolius Roxb.) using response surface

methodology. The Scientific World Journal. 523120.

https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/523120

15. Goni, I.;

Hervert-Hernandez, D. 2011. By-Products from Plant Foods are Sources of Dietary

Fibre and Antioxidants. Phytochemicals - Bioactivities and Impact on Health.

https://doi.org/10.5772/27923

16. Grochowski,

D. M.; Skalicka-Woźniak, K.; Orhan, I. E.; Xiao, J.; Locatelli, M.; Piwowarski,

J. P.; Granica, S.; Tomczyk, M. 2017. A comprehensive review of agrimoniin.

Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1401(1): 166-180.

https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13421

17. Kalinowska,

M.; Bielawska, A.; Lewandowska-Siwkiewicz, H.; Priebe, W.; Lewandowski, W.

2014. Apples: Content of phenolic compounds vs. variety,

part of apple and cultivation model, extraction of phenolic compounds,

biological properties. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 84: 169e188-188.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.09.006

18. Kasikci, M.

B.; Bagdatlioglu, N. 2016. Bioavailability of quercetin. Current Research in

Nutrition and Food Science. 4: 146-151. https://doi.org/10.12944/CRNFSJ.4.Special-Issue-October.20

19. Kingori, S.

M.; Ochanda, S. O.; Koech, R. K. 2021. Variation in Levels of Flavonols

Myricetin, Quercetin and Kaempferol - In Kenyan Tea (Camellia sinensis L.)

with Processed Tea Types and Geographic Location. Open Journal of Applied

Sciences. 11: 736-749. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojapps.2021.116054

20. Lachowicz,

S.; Oszmiański, J.; Rapak, A.; Ochmian, I. 2020. Profile and content of

phenolic compounds in leaves, flowers, roots, and stalks of sanguisorba

officinalis l. Determined with the LC-DAD-ESI- QTOF-MS/MS analysis and their in

vitro antioxidant, antidiabetic, antiproliferative potency.

Pharmaceuticals. 13(8): 1-22. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13080191

21. Landete, J.

M. 2011. Ellagitannins, ellagic acid and their derived metabolites: A review

about source, metabolism, functions and health. Food Research International.

44(5): 1150-1160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2011.04.027

22. Li, W.;

Yang, R.; Ying, D.; Yu, J.; Sanguansri, L.; Augustin, M. A. 2020. Analysis of

polyphenols in Apple pomace: A comparative study of different extraction and

hydrolysis procedures. Industrial Crops and Products. 147.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112250

23. Lončarić,

A.; Matanović, K.; Ferrer, P.; Kovač, T.; Šarkanj, B.; Babojelić, M. S.; Lores,

M. 2020. Peel of traditional apple varieties as a great source of bioactive

compounds: Extraction by micromatrix solid-phase dispersion. Foods. 9(1): 4-6.

https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9010080

24.

Mercado-Mercado, G.; Montalvo-González, E.; González-Aguilar, G. A.;

Alvarez-Parrilla, E.; Sáyago-Ayerdi, S. G. 2018. Ultrasound-assisted extraction

of carotenoids from mango (Mangifera indica L. ‘Ataulfo’) by-products on

in vitro bioaccessibility. Food Bioscience. 21: 125-131.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2017.12.012

25. Nowicka, A.;

Kucharska, A. Z.; Sokół-Łętowska, A.; Fecka, I. 2019. Comparison of polyphenol

content and antioxidant capacity of strawberry fruit from 90 cultivars of

Fragaria × ananassa Duch. Food Chemistry. 270: 32-46.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.07.015

26. Oszmiański,

J.; Wojdyło, A.; Gorzelany, J.; Kapusta, I. 2011. Identification and

characterization of low molecular weight polyphenols in berry leaf extract by

HPLC-DAD and LC-ESI/MS. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 59:

12830-12835. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf203052j

27. Putnik, P.;

Bursać Kovačević, D.; Režek Jambrak, A.; Barba, F. J.; Cravotto, G.; Binello,

A.; Lorenzo, J. M.; Shpigelman, A. 2017. Innovative “green” and novel

strategies for the extraction of bioactive added value compounds from citrus

wastes - A review. Molecules. 22(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22050680

28. Rana, R.;

Gulliya, B. 2019. Chemistry and Pharmacology of Flavonoids- A Review. Indian

Journal of Pharmaceutical Education and Research. 53: 8-20.

https://doi.org/10.5530/ijper.53.1.3

29.

Rodríguez-Arzuaga, M.; Piagentini, A. M. 2018. New antioxidant treatment with

yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis) infusion for fresh-cut apples:

Modeling, optimization, and acceptability. Food Science and Technology

International. 24(3): 223-231. https://doi.org/10.1177/1082013217744424.

30. Simirgiotis,

M. J.; Schmeda-Hirschmann, G. 2010. Determination of phenolic composition and

antioxidant activity in fruits, rhizomes and leaves of the white strawberry (Fragaria

chiloensis spp. chiloensis form chiloensis) using HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS and free

radical quenching techniques. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 23(6):

545-553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2009.08.020

31. UNEP. 2021.

Food Waste Index Report 2021. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-indexreport-2021

(accessed 2 July 2022).

32. Van de

Velde, F.; Grace, M. H.; Esposito, D.; Pirovani, M. É.; Lila, M. A. 2016.

Quantitative comparison of phytochemical profile, antioxidant, and

anti-inflammatory properties of blackberry fruits adapted to Argentina. Journal

of Food Composition and Analysis. 47: 82-91.

https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JFCA.2016.01.008

33.

Villamil-Galindo, E.; Van de Velde, F.; Piagentini, A. M. 2020. Extracts from

strawberry by-products rich in phenolic compounds reduce the activity of apple

polyphenol oxidase. LWT, 133(May); 110097.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2020.110097

34.

Villamil-Galindo, E.; Van de Velde, F.; Piagentini, A. M. 2021. Strawberry

agro-industrial by-products as a source of bioactive compounds: effect of

cultivar on the phenolic profile and the antioxidant capacity. Bioresources and

Bioprocessing. 8(1): 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-021-00416-z

35.

Villamil-Galindo, E.; Piagentini, A. M. 2022a. Sequential ultrasound-assisted

extraction of pectin and phenolic compounds for the valorisation of ‘Granny

Smith’ apple peel. Food Bioscience. 49(August); 101958.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2022.101958

36.

Villamil-Galindo, E.; Antunes-Ricardo, M.; Piagentini, A. M.; Jacobo-Velázquez,

D. A. 2022b. Adding value to strawberry agro-industrial by-products through

ultraviolet A-induced biofortification of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory

phenolic compounds. Front. Nutr. 9:1080147. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.1080147.