Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 57(2). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2025.

Original article

Compensatory

Growth in Pinus ponderosa (Dougl Ex Laws) Plantations Under Early

Silvicultural Treatments

Crecimiento

compensatorio en plantaciones de Pinus ponderosa (Dougl Ex Laws) bajo

tratamientos silviculturales tempranos

Andrea Alejandra

Medina2,

Marcos Ancalao1,

Matías Horacio

Saihueque1

1Campo Anexo San Martín - IFAB (INTA - CONICET)- Instituto de

Investigaciones Forestales y Agropecuarias de Bariloche. Ruta Nacional N° 40 Km

1911. C. P. 8430. Paraje Las Golondrinas. Lago Puelo. Chubut. Argentina.

2Universidad Nacional del Comahue. Centro Regional Universitario

San Martín de los Andes (CRUSMA). Pasaje de la Paz 235. San Martín de los

Andes. C. P. 8370. Neuquén. Argentina.

*letourneau.federico@inta.gob.ar

Abstract

Early pruning and

thinning in Pinus ponderosa, plantations in Andean Patagonia triggered

compensatory growth, characterized by greater trunk growth and structural

adjustments. We used a factorial design and mixed-effects models to evaluate

stem growth, crown light dynamics, tracheid length (TL), foliar biomass (FB),

wood density (WD), and Huber values (Hv) five years after treatment. Trees

under combined pruning and thinning (PT) showed the greatest basal area

increment, indicating resource reallocation to supportive structures despite

early foliage loss. Pruned trees maintained higher Hv and achieved partial

recovery of FB. Tracheid elongation was greatest in treated trees, suggesting

accelerated xylem maturation, while WD remained unchanged. These results

demonstrate the structural plasticity of P. ponderosa, which maintains

hydraulic function and growth after canopy disturbance. Our findings provide

useful guidance for silvicultural planning in temperate plantations.

Keywords: compensatory

growth, hydraulic architecture, adaptive response

Resumen

Los tratamientos

tempranos de poda y raleo en plantaciones de Pinus ponderosa en la

Patagonia Andina provocaron respuestas de crecimiento compensatorio,

evidenciadas por un mayor desarrollo del fuste y ajustes estructurales.

Mediante un diseño factorial y modelos de efectos mixtos, se evaluaron el

crecimiento del tallo, la dinámica de luz en la copa, la longitud de traqueidas

(TL), la biomasa foliar, la densidad de la madera y la razón de Huber (Hv)

cinco años después del tratamiento. Los árboles sometidos al tratamiento

combinado de poda y raleo (PT) mostraron el mayor incremento en el área basal,

indicando una reasignación de recursos hacia estructuras de sostén a pesar de

la pérdida foliar inicial. Los árboles podados mantuvieron valores elevados de

Hv y lograron una recuperación intermedia de biomasa foliar, mientras que la

elongación de traqueidas fue mayor en los árboles tratados, lo que sugiere una

maduración acelerada del xilema. La densidad de la madera no se vio afectada.

Estos resultados demuestran la plasticidad estructural de P. ponderosa,

evidenciando su capacidad para mantener la funcionalidad hidráulica y sostener

el crecimiento ante modificaciones en la copa. Los hallazgos aportan

herramientas útiles para la planificación silvícola en plantaciones templadas.

Palabras clave: crecimiento

compensatorio, arquitectura hidráulica, respuesta adaptativa

Originales: Recepción: 20/11/2023 - Aceptación: 24/10/2025

Introduction

Pinus ponderosa is the most

widespread conifer species in forest plantations in Andean Patagonia, Argentina

(24). Its cultivation

in ecotone zones has government support for its establishment and silvicultural

management. This species shows intermediate growth and numerous basal branches

requiring pruning to reduce fire risk or improve wood quality. Forest managers

must apply these cultural practices at an early, pre-commercial thinning stage

for these cultural practices to be effective. However, researchers have not

fully clarified how pruning and thinning affect early tree growth and

development.

Previous studies

have explored the influence of pruning and planting density on Pinus

ponderosa’s growth and physiological performance. For Gyenge et

al. (2009, 2010) demonstrated that pruning temporarily reduces diameter growth,

while planting density significantly affects resource availability and

individual tree growth. Additionally, Gyenge et al. (2012) analyzed responses

to water stress under different competition levels, showing short- and

long-term physiological adjustments. Similarly, Martínez-Meier et al. (2015) highlighted that

intraspecific competition alters the wood structure in high-density stands,

increasing earlywood density and reducing the hydraulic efficiency of trees,

affecting their ability to respond to water stress conditions.

Cambial maturation

is a key process in woody plants. It produces secondary xylem composed of

tracheids and other cellular elements. Tracheid size is a key indicator of this

maturation, influencing both hydraulic and mechanical function (13). In P.

ponderosa from this region, tracheid length (TL) increases during the

transition from juvenile to mature wood (17,

34).

TL in conifers also

correlates with tracheid diameter (30). Together, these

traits determine water transport efficiency through the xylem. Therefore, TL

provides valuable information on cambial maturation and its impact on wood

function and quality.

Pine productivity

depends strongly on canopy structure, including crown shape, leaf area index,

leaf distribution, and shoot architecture. Tree growth is directly related to

the ability to intercept solar radiation (31,

32, 33). As trees grow, vertical foliage distribution generates

self-shading and reduces light to lower branches. This loss of light often

triggers crown recession, the shedding of shaded leaves, which strongly

influences growth dynamics (7, 15).

These conditions alter biomass partitioning among foliage,

branches, and trunk. After pruning, they also modify the relationship between

conductive tissue and leaf biomass (14). The Huber value

(Hv), defined as the ratio of xylem cross-sectional area (G) to total leaf

biomass (FB), is a key indicator of hydraulic function (23). Because gas

exchange occurs through the leaf surface, predicting biomass partitioning

requires considering both G and FB.

Silvicultural

practices modify this functional relationship. Pruning reduces active leaf

area, temporarily increasing Hv. This may enhance the ability of conductive

tissue to supply water to residual foliage but can cause short-term hydraulic

imbalance during drought (9, 21). In contrast,

thinning reduces competition and promotes both greater leaf area and conductive

tissue, thereby enhancing growth efficiency (11).

These responses

depend on treatment intensity, initial stand conditions, and resource

availability. To analyze them, we used linear mixed-effects models (MEMs). MEMs

decompose variability into components associated with treatments and site or

individual differences (4, 19, 35). They also handle

covariates effectively by adjusting for interactions and accounting for

dependencies such as repeated or nested data. This approach provides more

precise comparisons between treatments and controls, even in heterogeneous or

unbalanced datasets.

This study

evaluates the effects of pruning and thinning on aboveground biomass allocation

in Pinus ponderosa. We focus on the relationship between foliar biomass

and trunk growth, and how this relationship changes after treatment. By

analyzing biomass partitioning, we aim to determine whether silvicultural

practices alter the balance between foliage and conductive tissue, thereby

influencing growth dynamics and hydraulic function.

We hypothesize that

pruning reduces photosynthetic capacity by removing basal branches. This

reduction may decrease trunk growth and alter basal taper due to changes in

branch structure and radial growth. In contrast, thinning increases light

availability for remaining trees and reduces intraspecific competition. This

effect may compensate for foliage loss caused by pruning, favoring resource

allocation to trunk growth and potentially modifying xylem structure.

Given tracheid size

is a key determinant of hydraulic efficiency, we further hypothesize that

pruning and thinning induce adjustments in TL. These changes may represent

compensatory responses to altered canopy structure and resource availability.

If Hv values in

pruned and thinned trees converge toward those of controls, this would indicate

xylem adjustment to balance water transport and mechanical support. However, if

Hv differences persist, this would suggest long-term changes in biomass

allocation and a departure from the expected proportionality between conductive

tissue and foliage biomass.

These hypotheses

guide the assessment of whether pruned trees adjust hydraulic and mechanical

structures to maintain functional integrity under different management regimes.

Additionally, analyzing TL as an indicator of xylem plasticity, together with

wood density (WD), offers insight into how structural adjustments help trees

cope with changes in resource availability and canopy modification.

Materials

and Methods

We conducted a

completely randomized factorial design in a 12-year-old P. ponderosa plantation

in northwestern Chubut Province, Argentina (latitude -42.300059°, longitude

-71.296954°). The stand had a mean diameter at breast height (dbh) of 8.5 cm

and a mean top height of 4.43 m, with 3 × 3 m spacing. The site quality index

ranged from 13 to 15 m (1).

Four silvicultural

treatments were applied: pruning (P), thinning (T), pruning plus thinning (PT),

and a control (C). Each treatment was assigned to five experimental units

(EUs), for 20 units.

Each EU was a 144

m² plot with 16 trees, separated by a buffer row. Before applying treatments,

and again five years later, we measured all trees (n = 215). Measurements

included dbh with dendrometric tape, crown base height (CrwH) with metric tape,

and total height (TH) with a Haglöf Vertex III hypsometer. The dbh point was

permanently marked for consistent re-measurement. The crown base was defined as

the lowest whorl with at least three live branches, provided that all branches

below were dead or pruned.

Pruning removed 50%

of the basal crown. Thinning eliminated 50% of the trees, primarily smaller and

less vigorous individuals.

At the end of the experiment, we randomly selected 32 trees for

destructive sampling. Each treatment contributed eight trees, with at least two

per EU.

Vertical light

profiles were measured immediately after treatment and again five years later.

Eight HOBO sensors were mounted horizontally on a rod at 1 m intervals, from

0.3 m above ground to the apex. The top sensor served as the reference. The rod

was positioned at the crown periphery in four cardinal directions per tree for

at least one minute each time. Mean light intensity was then calculated per

tree, and integrated light intensity (ILI) along the crown was obtained using

Simpson’s rule (3).

Five years after

treatment, we felled the sampled trees and collected stem disks at stump height

(0.1 m) and at breast height (1.3 m). Polished and digitized discs were

analyzed with Map Maker v3.5 to measure total cross-sectional area (including

bark) and under-bark area. The latter represented woody tissues without

separating xylem and phloem. Bark proportion was also compared among treatments

and excluded from further analyses. Annual ring areas corresponding to the experimental

period were extracted to calculate cross-sectional area increment at both

heights, incGdbh and incGstump, respectively.

Tracheid length

(TL) was assessed in two annual rings per tree-one formed before and four years

after treatment. Wood samples corresponding to each ring were macerated

following the Franklin

(1937)

technique. Tracheids were measured under an optical microscope at 40×

magnification equipped with an ocular micrometer, following the anatomical

measurement standards of the IAWA (2004) and the

recommendations of Muñiz

and Coradin (1991). A total of 1,920 tracheids were measured (30 tracheids × 2

rings × 32 trees).

In addition,

oven-dried wood samples were used to determine anhydrous density at breast

height (2 annual rings × 32 trees; n = 64 samples). For this purpose, samples

were first saturated in water to determine their saturated weight, then

air-dried for 24 h, and subsequently oven-dried at 103°C to obtain anhydrous

weight. Between drying and weighing, samples were kept in a desiccator with

silica gel to prevent moisture absorption. Basic density was then calculated

using saturated and anhydrous weights, applying the maximum moisture content

formula described by Smith (1954).

We estimated total

tree foliar biomass (FBtree) in two steps. First, we developed an allometric

model predicting needle biomass from branch diameter (FBbranch), using 59 trees

from 15 regional plots.

These trees

represented a wide range of sizes (dbh: 5-38 cm; height: 3-21 m; crown length:

1.5-15.5 m; age: 9-34 years). One branch per tree was sampled. Twigs and

needles were separated, oven-dried at 60 °C, and weighed. The branch diameter

was measured 5 cm from the insertion using a digital caliper. In a second step

branch model was then applied to all branches of the sample trees to estimate

FBtree. Then we fitted a mixed-effects model (MEM) to predict FBtree using

“crown length × dbh²” as the main predictor. The model was validated with a

jackknife resampling procedure (5, 8).

We also tested

whether site quality (intercept growth, 1) was a significant covariate. The

allometric equation for branch biomass was: FBbranch [g] = 0.299 × dbh [mm]^2.186. Following Nakagawa and Schielzeth (2013), this model

explained 84% of the variance (marginal R² = 0.84). For FBtree, the marginal R²

was 0.859, with no significant effect of site quality. We therefore applied the

following equation to the factorial experiment: FBtree [kg] = 91.20 × crown

length [m] × dbh² [m²].

Statistical

analyses addressed the following variables: 1) incGdbh, 2) the relationship of

incGdbh vs Hv and FBtree, 3) the relationship of incGdbh vs incGstump, 4) TL,

5) WD, and 6) Hv.

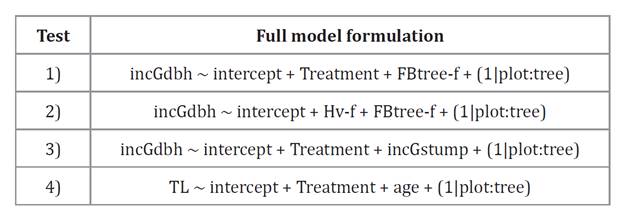

We fitted MEMs for

variables 1), 2), 3), and 4) (table 1), and assessed fixed effects with likelihood ratio tests (LRT).

For all variables,

treatment differences were tested with Tukey-adjusted pairwise comparisons

using estimated marginal means (EMMs) (16). MEMs were adjusted according to Bates et

al. (2015). All analyses were performed in R (2021).

The general model

structure was:

y ∼ Fixed factors + Covariates + (1 | Grouping factor).

Specific cases for variables 1)- 3) are detailed in table 1.

Table 1. Full

MEMs formulations to perform tests. incGdbh: the

dependent cross-sectional area increments under bark at breast height.

Tabla

1. Descripción del modelo lineal

completo de efectos mixtos utilizados para los análisis. incGdbh:

variable dependiente, incremento del área transversal del tronco bajo la

corteza a la altura del pecho.

The

fixed effects factor was silvicultural treatment with levels C, P, PT, and T as

Treatment. Covariates FBtree-f: Tree foliar biomass at the end of the

experiment, Hv-f: Huber value at the end of the experiment, incGstump:

cross–sectional area increments under bark at stump height. Random effects:

grouping the individual tree nested in the EU, experimental unit, or plot.

El

factor de efectos fijos fue el tratamiento silvícola con niveles C, P, PT y T.

Covariables: FBtree-f: biomasa foliar del árbol al final del experimento; Hv-f:

valor de Huber al final del experimento; incGstump: incremento del área

transversal del tronco bajo la corteza a la altura del tocón. Efectos

aleatorios: agrupamiento del árbol individual anidado en la unidad experimental

(EU), o parcela.

Results

Bark proportion at

breast height did not differ among treatments (LRT; F = 0.582, df = 3, p =

0.633). Bark represented 19.7 ± 3.1% of trunk cross-sectional area. It was

excluded from all subsequent analyses.

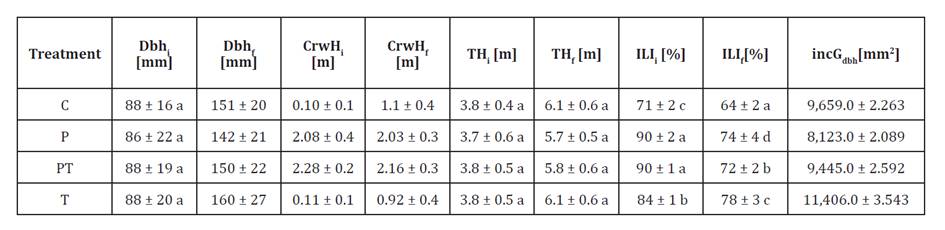

At the beginning of

the experiment, integrated light intensity (ILI-i) (table 2) was higher in

pruned treatments P (90.4 ± 2%) and PT (90.1 ± 1%) than in control C (70.8 ±

2%) and thinning T (84.2 ± 1%). The similarity between P and PT indicates that

pruning was the main factor increasing crown light exposure, primarily by

raising crown base height (CrwH) (table 2).

Table 2. Tree

biometric values in the factorial experiment.

Tabla

2. Valores biométricos observados de

los árboles en el experimento factorial.

Mean

± standard deviation for each treatment. Dbh: diameter at 1.3 m height, CrwH:

live crown base height, TH: total height, ILI: integrated light intensity,

incGdbh: increment in cross-sectional area of woody tissues at breast height.

Suffixes “-i” and “-f” denote the initial and final moments of the experiment.

Different letters show significant statistical differences.

Media

± desviación estándar para cada tratamiento. Dbh: diámetro a 1,3 m de altura,

CrwH: altura de la base de la copa viva, TH: altura total, ILI: intensidad

lumínica integrada, incGdbh: incremento del área seccional de tejidos leñosos a

la altura del pecho. Los sufijos “i” y “f” indican los momentos inicial y final

del experimento. Letras distintas indican diferencias estadísticas

significativas.

By the end of the

experiment, integrated light intensity (ILI-f) decreased in all treatments: -

9.9% C,

-18.6% P, - 20.9% PT , - 7.5% T.

Despite this reduction, pruned treatments retained the highest final values-P

(73.6%) and PT (71.3%)-showing a lasting structural effect on canopy light

penetration.

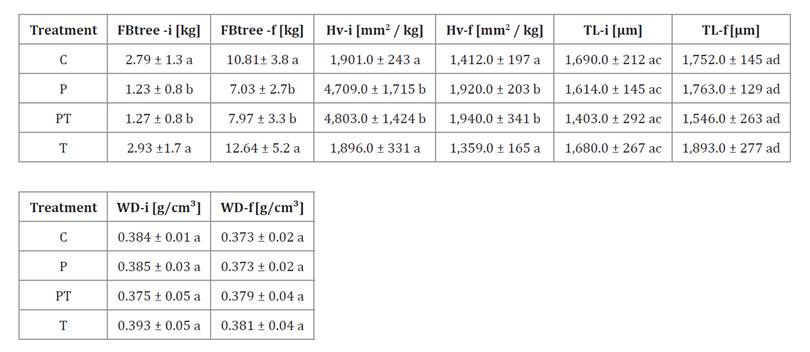

Leaf biomass (FBtree) increased in all treatments during the

experiment (table

3).

The magnitude of change, however, differed among treatments. Control (C) and

thinning (T) reached the highest final values, 10.8 ± 3.8 kg and 12.6 ± 5.2 kg,

respectively. Both started from similar baselines, 2.8 ± 1.3 kg and 2.9 ± 1.7

kg, corresponding to increases of 287% and 331%.

Table 3. Functional

and structural values of tree traits in the factorial experiment.

Tabla

3. Valores funcionales y estructurales

observados de los atributos del árbol en el experimento factorial.

FBtree:

tree foliar biomass, Hv: Huber value, TL: tracheid length, and WD: wood

density. Mean ± standard deviation. Different letters show significant

statistical differences. For TL-i and TL-f, the first letter compares

treatment, and the second letter compares experimental moment - initial vs final-

for the same treatment. Suffixes “i” and “f” denote the initial and final

moments of the experiment.

FBtree:

biomasa foliar del árbol, Hv: valor de Huber, TL: longitud de traqueidas y WD:

densidad de la madera. Media ± desviación estándar. Letras distintas indican

diferencias estadísticas significativas. Para TL-i y TL-f, la primera letra

corresponde a la comparación entre tratamientos y la segunda al momento del

experimento -inicial vs final- para el mismo tratamiento. Los sufijos

“i” y “f” indican los momentos inicial y final del experimento.

In contrast,

pruning treatments began with significantly lower FBtree due to foliage

removal. Initial values were 1.2 ± 0.8 kg in P and 1.3 ± 0.8 kg in PT. By the

end, both reached intermediate levels: 7.0 ± 2.8 kg in P and 8.0 ± 3.3 kg in

PT. These increases of 472% and 528% indicate compensatory foliage regrowth in

pruned trees, while unpruned treatments followed steady canopy expansion.

Initial Hv-i (figure 1; table 3) was substantially

higher in P (4,709 ± 1,715 mm²/kg) and PT (4,803 ± 1,424 mm²/kg) than in C

(1,901 ± 243 mm²/kg) and T (1,896 ± 331 mm²/kg). This pattern reflected the

immediate pruning-induced reduction in leaf biomass. Over time, Hv declined in

all treatments, showing a rebalancing between conductive tissue and foliage.

The greatest declines occurred in P (-59.2%) and PT (-59.6%). Yet, both

treatments retained higher final Hv values than controls, indicating a

persistent structural effect of pruning.

Dots

jittered to provide a more comprehensive understanding.

Los

puntos están desplazados (jitter) para facilitar su visualización.

Figure

1. Huber values (Hv) for initial and final treatment

moments.

Figura

1. Valores observados de la razón de

Huber (Hv) al inicio y al final de los tratamientos.

Tracheid length

varied widely but increased in all treatments (figure 2), consistent with

age-related xylem maturation (Test 4 in table 1; AIC = 864.9,

model p = 0.0001, Age coefficient = 28.35, p = 0.003). Increases were largest

in T (+12.7%) and PT (+10.2%), followed by P (+9.2%) and C (+3.7%). These

results suggest that silvicultural treatments may accelerate tracheid

elongation. Although differences were not statistically significant, treatment

effects revealed biologically relevant trends.

Figure

2. Tracheid length distribution, before and after

treatment (C control, P Pruning, PT Pruning plus thinning, T thinning).

Figura

2. Distribución de la longitud de

traqueida, antes y después del tratamiento (C testigo, P poda, PT poda y raleo,

T raleo).

Wood density remained stable across treatments during the five

years (table

3).

Initial values ranged from 0.375 to 0.393 g/cm³. Final values showed only

slight variation (0.373-0.381 g/cm³). No significant differences were detected,

indicating that treatments did not markedly affect wood density.

In Test 1 (table

1;

figure

3),

the full model with treatments and FBtree-f explained trunk growth variation

(LRT: χ² = 422, df = 7, p < 2.2e-16). Predicted intercepts were highest for

PT (5,341.0 mm²), followed by P (4,492.0 mm²), T (4,013.0 mm²), and C (3,315.0

mm²). PT differed significantly from C (Δ = 1,626.0 ± 454 mm², p = 0.007). The

PT-T contrast approached significance (p = 0.076), suggesting a trend. A

complementary model using Hv-f and FBtree-f (Test 2) had similar explanatory

power (AIC = 3,556.5 vs. 3,547.8). This supports the hypothesis that

hydraulic adjustments mediate post-treatment growth.

Predictions

according to the full model of test 1.

Predicciones

según el modelo completo del test 1.

Figure

3. Observed (dots) and predicted (lines) values of

increment of cross-sectional trunk area (incGdbh) for treatments along tree

foliar biomass at the end of the experiment (FBtree-f).

Figura

3. Valores observados (puntos) y

predichos (líneas) del crecimiento del área transversal del tronco (incGdbh)

para los tratamientos, en función de la biomasa foliar final del árbol

(FBtree-f).

Finally, the

proportionality incGdbh vs incGstump, was not significantly affected by

treatments (Test 3, χ² = 1.6198, df = 3, p-value = 0.6549). Stem allocation

patterns, therefore, remained consistent despite pruning.

Discussion

Early silvicultural

treatments in Pinus ponderosa plantations produced clear changes in

growth and crown structure. Pruning and thinning, especially when combined,

enhanced trunk growth rates despite the initial reduction in foliar biomass.

Pruning increased crown light penetration, stabilized crown architecture, and

promoted compensatory foliage development.

These treatments also triggered structural and functional

adjustments. Pruned trees maintained higher Huber values (Hv) than controls

during the study period. Tracheid length increased across all treatments, with

greater elongation in treated trees. These anatomical shifts, although not

always linked to higher trunk growth, indicate xylem maturation adjustments

that may improve hydraulic efficiency.

The increased trunk

growth in the pruning plus thinning treatment (PT) supports the hypothesis that

P. ponderosa shows compensatory responses to early canopy interventions.

Despite foliage loss from pruning, treated trees -particularly under PT-

displayed greater xylem area increments, likely reallocating resources to

supportive structures. These dynamics align with compensatory growth theory,

which describes adaptive responses to sudden reductions in foliage (21,

22).

Our findings also

indicate that P. ponderosa adjusts hydraulic architecture without

compromising wood density. The separation between enhanced structural growth and

stable density suggests anatomical plasticity via tracheid elongation and crown

reconfiguration, not faster or lower-quality wood formation..

This result agrees with previous studies (9,

10, 11), which reported morphological and physiological adjustments

under pruning, thinning, and drought, including crown restructuring and

improved water-use efficiency, without changes in wood density. Likewise, Martínez-Meier

et al. (2015) detected fine-scale density variations with microdensitometry,

while our ring-level estimates revealed no significant effects, reinforcing the

idea of macro-anatomical rather than biochemical adaptation.

Although this study

focused on structural traits, the compensatory responses in trunk growth,

foliage regrowth, and xylem anatomy likely reflect ecophysiological

adjustments. Canopy opening in pruned treatments increased light exposure,

possibly enhancing stomatal conductance and photosynthetic rates. These changes

likely promoted carbon assimilation and foliage regeneration (20,

31).

Tracheid elongation

and shifts in Huber values further suggest adjustments in stem hydraulic

architecture. Such changes may improve specific hydraulic conductivity and

support water transport to the regenerating canopy (10,

13, 30). Reduced competition in thinned plots likely improved water

availability, favoring higher leaf water potential and maintaining stomatal

function (9, 11). Although not directly measured,

these responses match known mechanisms of resource reallocation and

water–carbon coupling in conifers under stress (15,

18).

These findings

refine the broader hypothesis by Fernández et al. (2011), who proposed that

Pinus species show lower physiological plasticity than Eucalyptus. While this

may hold at the biochemical level, our results highlight structural

adaptability in P. ponderosa. This species compensates for canopy

changes by adjusting conduit dimensions and crown structure to maintain

hydraulic function while keeping wood density stable. Such capacity has

important implications for resilience and productivity under silvicultural

management and environmental variability.

This study has

several limitations: a small sample size, a five-year monitoring period, and

the absence of direct physiological measurements. Another limitation is that

our design does not explicitly account for soil or landform heterogeneity,

which can modulate radial growth patterns in arid environments (27). Future work

should extend monitoring, include direct evaluations of stomatal conductance, photosynthesis,

and hydraulic conductivity, assess vascular reuse after pruning, and

incorporate spatial variation in site conditions. These efforts will help

clarify the functional mechanisms driving compensatory responses in P.

ponderosa.

Conclusions

This study confirms

that early pruning and thinning in Pinus ponderosa plantations trigger

compensatory growth, especially when both treatments are combined. The main

effects included greater conductive tissue area, partial recovery of foliar

biomass, and tracheid elongation, while wood density remained unchanged.

These structural adjustments support the hypothesis that

hydraulic and anatomical plasticity drive the observed responses. The findings

highlight the value of early silvicultural interventions to enhance growth and

maintain hydraulic function, providing guidance for management in temperate

conifer plantations. A deeper understanding of physiological and structural

adjustments will further inform strategies to optimize productivity and

resilience in P. ponderosa, especially in the early stages.

Acknowledgments

We thank the support staff of Campo Anexo San Martín – INTA for

assistance during sampling and Ea. El Maitén for providing the experimental

site. We are also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive

feedback, which improved the quality and rigor of the manuscript.

1. Andenmatten, E.;

Letourneau, F. J. 1997. Funciones de intercepción de crecimiento para

predicción de índice de sitio en pino ponderosa, de aplicación en la Región

Andino Patagónica de Río Negro y Chubut. Revista Quebracho. 5: 5-9.

2. Bates, D.;

Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. 2015. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models

Using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software. 67(1): 1-48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

3. Chapra, S. C.;

Canale, R. P. 2015. Numerical Methods for Engineers, 7th

ed. McGraw- Hill Education.

https://archive.org/details/numerical-methods-for-engineers-7th-edit/mode/2up

4. Demidenko, E.

2013. Mixed models: Theory and applications with R (2nd

ed.). John Wiley & Sons. (Wiley Series in Probability and

Statistics). p 717.

5. Fernández, M.

E.; Fernández Tschieder, E.; Letourneau, F. J.; Gyenge, J. E. 2011. Why do

Pinus species have different growth dominance patterns than Eucalyptus species?

A hypothesis based on differential physiological plasticity. Forest Ecology and

Management. 261(6): 1061-1068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2010.12.028

6. Franklin, G. L.

1937. Permanent preparations of macerated wood fibres. Tropical Woods. 49:

21-22.

7. Garber, S. M.;

Monserud, R. A.; Maguire, D. A. 2008. Crown recession patterns in three conifer

species of the Northern Rocky Mountains. Forest Science. 54(6): 633-646.

https://doi. org/10.1093/forestscience/54.6.633

8. Gregoire, T. G.

1984. The jackknife: A resampling technique with application to linear models.

Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 14(3): 483-487.

https://doi.org/10.1139/x84-092

9. Gyenge, J.;

Fernández, M. E.; Schlichter, T. 2009. Effect of pruning on branch production

and water relations in widely spaced ponderosa pines. Agroforest Syst. 77:

223-235. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10457-008-9183-9

10. Gyenge, J. E.;

Fernández, M. E.; Schlichter, T. M. 2010. Effect of stand density and pruning

on growth of ponderosa pines in NW Patagonia, Argentina. Agroforestry Systems.

78(3): 233-241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-009-9240-z

11. Gyenge, J.;

Fernández, M. E.; Varela, S. A. 2012. Short-and long-term responses to seasonal

drought in ponderosa pines growing at different plantation densities in

Patagonia, South America. Trees. 26(6): 1905-1917.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-012-0759-7

12. IAWA Committee.

2004. IAWA list of microscopic features for softwood identification. IAWA

Journal. 25(1): 1-70. https://doi.org/10.1163/22941932-90000349

13. Lachenbruch,

B.; McCulloh, K. A. 2014. Traits, properties, and performance: how woody plants

combine hydraulic and mechanical functions in a cell, tissue, or whole plant.

New Phytologist. 204(4): 747-764. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13035

14. Långström, B.;

Hellqvist, C. 1991. Effects of different pruning regimes on growth and sapwood

area of Scots pine. Forest Ecology and Management. 44: 239-254.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0378- 1127(91)90011-J

15. Ledermann, T.

2011. A non-linear model to predict crown recession of Norway spruce (Picea

abies [L.] Karst.) in Austria. Eur J Forest Res.

130: 521-531.

16. Lenth, R. V.

2024. Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. R package

version.

17. Letourneau, F.

J.; Medina, A. A.; Pampiglioni, A.; Ancalao, M.; Saihueque, M.; González, A.

2016. Efecto de tratamientos silvícolas sobre la maduración de la madera de una

plantación de Pino ponderosa. V Jornadas Forestales Patagónicas.

18. Li, C.; Barclay,

H.; Roitberg, B.; Lalonde, R. 2021. Ecology and Prediction of Compensatory

Growth: From Theory to Application in Forestry. Frontiers in Plant Science. 12.

https://doi. org/10.3389/fpls.2021.655417

19. Macêdo Araújo

da Silva, D.; Pereira da Silva Santos, N.; de Sousa Araújo Santos, E. E.; Alves

Pereira, G.; Barbosa da Silva Júnior, G.; Gomes da Cunha, J. 2022. Effects of

formative and production pruning on fig growth, phenology, and production.

Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo.

Mendoza. Argentina. 54(1): 13-24. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.061

20. Martínez-Meier,

A.; Fernández, M. E.; Dalla-Salda, G.; Gyenge, J.; Licata, J.; Rozenberg, P.

2015. Ecophysiological basis of wood formation in ponderosa pine: Linking water

flux patterns with wood microdensity variables. Forest Ecology and Management.

346: 31-40. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2015.02.021

21. Maschinski, J.;

Whitham, T. G. 1989. The continuum of plant responses to herbivory: The

influence of plant association, nutrient availability, and timing. The American

Naturalist. 134(1): 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1086/284962

22. McNaughton, S.

J. 1983. Compensatory plant growth as a response to herbivory. Oikos. 40(3):

329-336. https://doi.org/10.2307/3544305

23. Mencuccini, M.;

Rosas, T.; Rowland, L.; Choat, B.; Cornelissen, H.; Jansen, S.; Kramer, K.;

Lapenis, A.; Manzoni, S.; Niinemets, Ü.; Reich, P. B.; Schrodt, F.;

Soudzilovskaia, N.; Wright, I. J.; Martínez-Vilalta, J. 2019. Leaf economics

and plant hydraulics drive leaf: wood area ratios. New Phytologist. 224(4):

1544-1556. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15998

24. Ministerio de Agroindustria. Unidad Para El Cambio

Rural-CIEFAP. 2017. Inventario de Plantaciones Forestales en Secano. Región

Patagonia. p. 136.

25. Muñiz, G.;

Coradin, V. 1991. Norma de procedimientos em estudios de anatomía de madeira.

II Gimnospermae. Brasília: Laboratorio de Produtos Florestais. Serie Técnica.

117 p.

26. Nakagawa, S.;

Schielzeth, H. 2013. A general and simple method for obtaining R² from

generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution.

4(2): 133-142. https:// doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210X.2012.00261.x

27. Piraino, S.;

Roig, F. A. 2024. Landform heterogeneity drives multi-stemmed Neltuma flexuosa

growth dynamics. Implication for the Central Monte Desert forest

management. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional

de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 56(1): 26-34. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.120

28. R Core Team.

2021. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for

Statistical Computing.

29. Smith, D. M.

1954. Maximum moisture content method for determining specific gravity of small

wood samples. Report N° 2014. USDA Forest Service. Forest Products Laboratory.

30. Sperry, J. S.;

Hacke, U. G.; Pittermann, J. 2006. Size and function in conifer tracheids and

angiosperm vessels. American Journal of Botany. 93(10): 1490-1500.

https://doi.org/10.3732/ ajb.93.10.1490

31. Wang, Y.; Liu,

Z.; Li, J.; Cao, X.; Lv, Y. 2024. Assessing the Relationship between Tree

Growth, Crown Size, and Neighboring Tree Species Diversity in Mixed Coniferous

and Broad Forests Using Crown Size Competition Indices. Forests. 15(633): 1-17.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ f15040633

32. Zeng, B. 2003.

Aboveground biomass partitioning and leaf development of Chinese subtropical

trees following pruning. Forest Ecology and Management 173: 135-144.

https://doi. org/10.1016/S0378-1127(01)00821-0

33. Zhu, Z.;

Kleinn, C.; Nölke, N. 2021. Assessing tree crown volume-a review. Forestry: An

International Journal of Forest Research. 94(1): 18-35.

https://doi.org/10.1093/forestry/cpaa037

34. Zingoni, M. I.;

Andia, I.; Mele, U. 2007. Longitud de traqueidas y madera juvenil en el fuste

de un árbol de pino ponderosa de 50 años-SO Neuquén. III Congreso

Iberoamericano de Productos Forestales IBEROMADERA 2007.

35. Zuur, A. F.; Ieno, E. N.; Walker, N. J.; Saveliev, A. A.;

Smith, G. M. 2009. Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R.

Springer Science & Business Media. https://doi.

org/10.1007/978-0-387-87458-6