Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 57(2). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2025.

Original article

Variations

of Atmospheric Emissions in the Biomass Burning of Tree Species as an

Environmental Indicator

Variaciones

de emisiones atmosféricas en la quema de biomasa de especies arbóreas como

indicador ambiental

Jorge Alonso Alcalá

Jáuregui1*,

María Fernanda

Ramírez Cubos1,

Ángel Natanael

Rojas Velázquez1,

Idrissa Diedhiou2,

María Flavia

Filippini3,

Daniela Cónsoli3,

Eduardo Martínez

Carretero4,

Juan Carlos

Rodríguez Ortiz1

Oscar Iván Guillén

Castillo1

Marcela Ontivero4

1Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí. Facultad de Agronomía y

Veterinaria. Km. 14.5 Carretera San Luis-Matehuala Apdo. Postal 32 CP 78321

Soledad de Graciano Sánchez. San Luis Potosí. México.

2Universidad EARTH. Las Mercedes de Guácimo. Guácimo 70602. Costa

Rica.

3Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias.

Catedra Química Agrícola. Almirante Brown 500. M5528AHB. Chacras de Coria.

Mendoza. Argentina.

4IADIZA (CONICET). Geobotánica y Fitogeografía. Mendoza.

Argentina.

*jorge.alcala@uaslp.mx

Abstract

Biomass burning

(BB) serves as both an energy source and an environmental indicator. This study

examined how CO₂ and fine particle emissions vary during the combustion of

biomass from three tree species to determine their contribution to

environmental pollution. Leave and stem samples were taken from A.

farnesiana (huizache) tree, S. molle (pirul), and P. laevigata (mesquite).

The dry biomass was thermally processed in a muffle furnace at temperatures

ranging from 50°C to 450°C. Emissions of CO₂, particles smaller than 2.5

microns (PM2.5),

particles smaller than 10 microns (PM10),

and total volatile organic compounds (TVOC) were measured. The highest emission

levels occurred during the pyrolysis process between 250°C and 450°C in both

leaves and stems. Among the leaves, the highest emissions of PM2.5 and PM10 were found in huizache,

while the highest values were found in mesquite stems. In terms of leaves,

mesquite had the highest CO₂ emissions, followed by huizache and pirul.

Regarding the stems, pirul had the highest atmospheric emissions of CO₂,

followed by huizache and mesquite. In all cases, emission levels exceeded the

limits established by Mexican and international environmental regulations,

indicating a significant risk to the environment and public health.

Keywords: Carbon dioxide,

fine particles, incineration temperature, permissible limits

Resumen

La quema de biomasa

(BB) sirve tanto como fuente de energía como indicador medioambiental. Este

estudio examinó las variaciones de las emisiones de CO₂ y partículas finas

durante la combustión de biomasa de tres especies de árboles para determinar su

contribución a la contaminación medioambiental. Se tomaron muestras de hojas y

tallos de A. farnesiana (huizache), S. molle (pirul) y P.

laevigata (mezquite). La biomasa seca se procesó térmicamente en un horno

de mufla a temperaturas que oscilaron entre 50°C y 450°C. Se midieron las

emisiones de CO₂, partículas menores de 2,5 micras (PM2.5),

partículas menores de 10 micras (PM10)

y compuestos orgánicos volátiles totales (TVOC). Los niveles más altos de

emisión se produjeron durante el proceso de pirólisis entre 250°C y 450°C,

tanto en las hojas como en los tallos. Entre las hojas, las emisiones más altas

de PM2.5 y PM10 se encontraron en el

huizache, mientras que los valores más altos se encontraron en los tallos del

mezquite. En cuanto a las hojas, el mezquite tuvo las emisiones más altas de

CO₂, seguido del huizache y el pirul. En cuanto a los tallos, el pirul tuvo las

emisiones atmosféricas más altas de CO₂, seguido del huizache y el mezquite. En

todos los casos, los niveles de emisión superaron los límites establecidos por

las regulaciones ambientales mexicanas e internacionales, lo que indica un

riesgo significativo para el medio ambiente y la salud pública.

Palabras clave: Dióxido de carbono,

partículas finas, temperatura de incineración, límites permisibles

Originales: Recepción: 18/04/2025 - Aceptación: 17/11/2025

Introduction

Biomass burning

(BB) is the combustion of plant materials, which are widely used for energy

production. It is increasingly recognized as an environmental indicator,

particularly of air quality. Energy sources can be broadly classified as solid

or non-solid fuels. The former includes coal, biomass, unprocessed wood,

charcoal, manure, and crop residues. The latter includes kerosene, liquefied

petroleum gas, natural gas, electricity, and others (8,

45, 51). Furthermore, BB is a significant contributor to air pollution

with global, regional, and local implications for air quality, public health,

and climate (21, 45). It emits trace

gases and particulate matter into the atmosphere (19). It emits trace

gases and particulate matter into the atmosphere. Therefore, the quantification

of emissions and their impact assessment have been studied in various regions

of the world (21, 45). In urban areas,

around 50% of households use solid fuels, primarily coal and biomass, for

energy, exposing themselves to the harmful effects of combustion residues. This

affects nearly 50% of the global population, i.e., over 3 billion people

(51). Biomass

originates from trees, agricultural crops, and other living plant materials.

Furthermore, burning is a common, cost-effective, and time-efficient method of

disposing of biomass residues from agricultural processes and other sectors.

This practice has become increasingly widespread during the pre- and

post-harvest seasons (41). From a health

perspective, CO₂ is produced when biomass burns efficiently. Oxygen from the

atmosphere combines with carbon from plants to produce CO₂ at a technological

level. In the field of biomass-to-energy conversion, several technologies are

in use, including combustion, anaerobic digestion (biogas plants), and

thermochemical pretreatment. Promising emerging technologies include thermal

gasification, torrefaction, and pyrolysis (33). The main

technologies used in experimentation to exploit organic waste or biomass focus

on chemical-biological processes, bioenergy, environmental treatment,

pyrolysis, gasification, combustion, synthesis, hydrolysis, fermentation, and

product separation (1). Other sources

indicate that biomass conversion technologies fall into three categories:

combustion, thermal gasification, and pretreatment. In pyrolysis, a

thermochemical route, biomass is heated between 400°C and 600°C in the absence

of oxygen. The process produces three products: solid charcoal, liquid

pyrolysis oil (bio-oil), and a gaseous product (33). Pyrolysis is

characterized by high heating rates, with temperature control close to 500°C (1,

12, 14). In contrast, torrefaction is considered a mild form of

pyrolysis (200°C<T<300°C) and is carried out in an inert atmosphere or

with steam. This brings the biomass into contact with a heating medium that

gradually raises its temperature by less than 50°C per minute until it reaches

200-300°C (13). In practice,

these burning processes release various pollutants, mainly gases and

particulate matter, into the atmosphere. These pollutants include formaldehyde

(HCHO), methane (CH₄), sulfur oxides (SOx), nitrogen oxides (NOx), carbon

monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO₂), and different sizes of respirable

particulate matter (PM3.5),

such as PM₁, PM2.5,

and PM₁₀ (9, 43, 51, 53, 55). The process is

cyclical because CO₂ and water are produced, which are then used in the

photosynthetic process to produce carbohydrates that form the basic components

of biomass (9). In contrast,

particulate matter emissions have been linked to severe damage, including

alterations in photosynthesis, changes in plant growth, and alterations in

plant reproduction (36). In line with

global monitoring efforts, the United Nations Agenda 2030 for Sustainable

Cities and Communities evaluates air quality by considering fine suspended

particles PM2.5 and PM10,

as indicators (38). PM2.5 is the environmental

factor posing the greatest health risk, contributing to over 4.1 million deaths

worldwide in 2016 (31). For instance, a study of 708 European urban

areas found that 22% of PM emissions came from urban cores and commuting areas.

The average contributions of industrial activity, agriculture, and road

transport were 18%, 17%, and 14%, respectively. Furthermore, 27% of the

emissions came from a group of cities in northern Italy, while eastern Europe

contributed more than 50% (58). The World Health

Organization (WHO) recommends annual mean exposures of 10 μg/m³ of PM2.5

and 20 μg/m³ of PM10 to minimize health

impacts (34, 40, 56). In Mexico,

NOM-021-SSA1-2021 establishes permissible values for suspended particulate

matter PM10 and PM2.5 in ambient air, including

evaluation criteria (25). Furthermore,

studies of air pollution by BB combine a series of variables and perspectives.

These variables and perspectives consider the spatial and temporal scales, as

well as the associated implications and impacts on human health, regional air

quality, ecosystem health, climate change, and intercontinental pollution (52). Along these lines,

studies of biomass derived from organic sources, such as agricultural and

forest residues and dedicated energy crops, aim to identify sustainable energy

options while evaluating their environmental impact, such as greenhouse gas

emissions (8, 26). The species Prosopis

laevigata (mesquite), Schinus molle (pirul), and Acacia

farnesiana (huizache) have been associated with studies on environmental

pollution in the state of San Luis Potosi (3,

4, 5, 6, 23). In some regions of Mexico, species such as mesquite (Prosopis

sp.) are used as a source of charcoal due to their calorific potential (23). This indicates

the need to explore alternatives to assess the impact of biochar (BB) on tree

species. In some cases, dry leaves, bark, and pruning residues are used as fuel

(45). Thus, this study

aimed to evaluate variations in atmospheric emissions from burning biomass

(stems and leaves) of these tree species to expand pollution research in San

Luis Potosi, Mexico. The hypothesis is that emissions differ among species and

between biomass types (leaves vs. stems), influencing compliance with

environmental regulations in a laboratory-scale pilot test under a controlled

pyrolysis/combustion process.

Materials

and Methods

The study was

conducted at Ejido Palma de la Cruz, Soledad de Graciano Sanchez, San Luis

Potosi, Mexico (24°14’58’’N and 100°51’53’’W; 1,836 m a. s. l.) (figure 1).

Figure

1. Study area and sampling points for biomass

collection.

Figura

1. Área de estudio y puntos de

muestreo de la colecta de biomasa.

Sample

Collection

Nine sampling points were randomly selected within stands

dominated by Prosopis laevigata, Acacia farnesiana, and Schinus

molle, focusing on individuals taller than two meters. For each species,

leaf and stem material was collected 1.6-1.8 meters above the ground after

flowering. The samples were transported to the laboratory. The leaves and stems

were separated, rinsed to remove dust and debris, and air-dried at room

temperature. Fresh and dry biomass weights (g) were recorded to estimate total

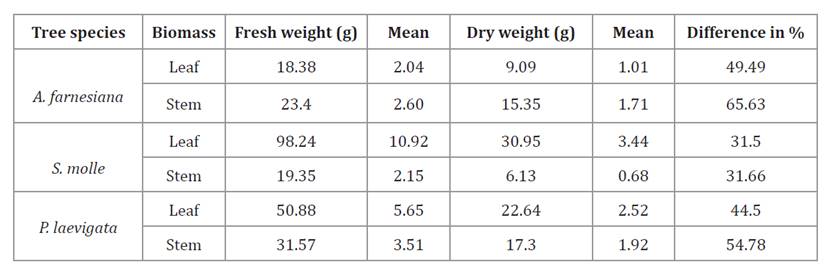

fresh weight per species and per plant organ (leaves and stems) (table 1). In total, nine

composite samples per species were obtained (n=9 per organ per species). To

determine the total dry weight per species, biomass was placed in a drying oven

at 60°C for 48 hours in a RIOSSA H-48-48 stove.

Table 1. Estimated

total fresh and dry biomass weight of the tree species (g).

Tabla

1. Estimación del peso fresco y seco

total de la biomasa de las especies arbóreas (g).

Measurement

of Incineration Gases and Atmospheric Particles

Ambient

concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO₂), particulate matter (particles smaller

than 2.5 and 10 microns), PM2.5,

PM₁₀, total volatile organic compounds, relative humidity, and temperature were

recorded before measurement. The dry weight generated by each species (leaf and

stem) was divided into six crucibles, each containing an average sample of 1.5

g, for the dry weight samples of leaves of each species. For the stems, four

crucibles were used with an average dry weight range of 1.5 g. This was done

because the total biomass of the leaves and stems of each species lost between

31.5% and 54.78% of their weight. To homogenize the distribution of biomass, an

average of 1.5 g per sample was used (table 1). This could be a

limitation to consider when increasing the amount of experimental dry biomass

in future studies. According to certain criteria of some authors, the biomass

was subjected to the pyrolysis process at temperatures ranging from 50°C to 450°C

(1,

12, 14).

The prepared

samples were incinerated in an electric muffle furnace (LabTech® Daiha Lantech

Co. LTD) at 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, 350, 400, and 450°C. Measurements of

CO₂ (ppm), PM2.5 (μ/m3),

PM10 (μ/m3),

TVOC (total volatile organic compounds, g/m3),

% relative humidity, and temperature (°C) were performed using HT-9600 (Dust

Particle Counter®) and BLATN Smart (Portable Air Quality Monitor®) equipment.

These devices were stabilized for an average of two hours for the environmental

measurement. Some methodological criteria regarding sample handling and

particle measurement were considered in previous studies (7). Results were

interpreted using guideline values from the United States Environmental

Protection Agency and the World Health Organization (34,

35, 40), as well as those referred to in the manuals of the measuring

equipment. Additionally, the Mexican Official Standard NOM-025-SSA1-2021 (25) was considered by

comparing the average emission values with the 24-h permissible limits

established by the standard of the real emission (maximum and minimum values).

Statistical

Analysis

The variables

included total and specific biomass (leaves and stems) by species, ambient

temperature, percent relative humidity, incineration temperatures, gas,

atmospheric particulate emissions, dry weight, and residual ash. The data were

analyzed using Minitab® software, version 16. Analysis of variance was used

with Tukey’s test at a significance level of p≤0.05. Correlation analysis

(Pearson correlation coefficient) and principal component analysis (PCA) were

also performed on all variables studied in this experiment.

Results

and Discussion

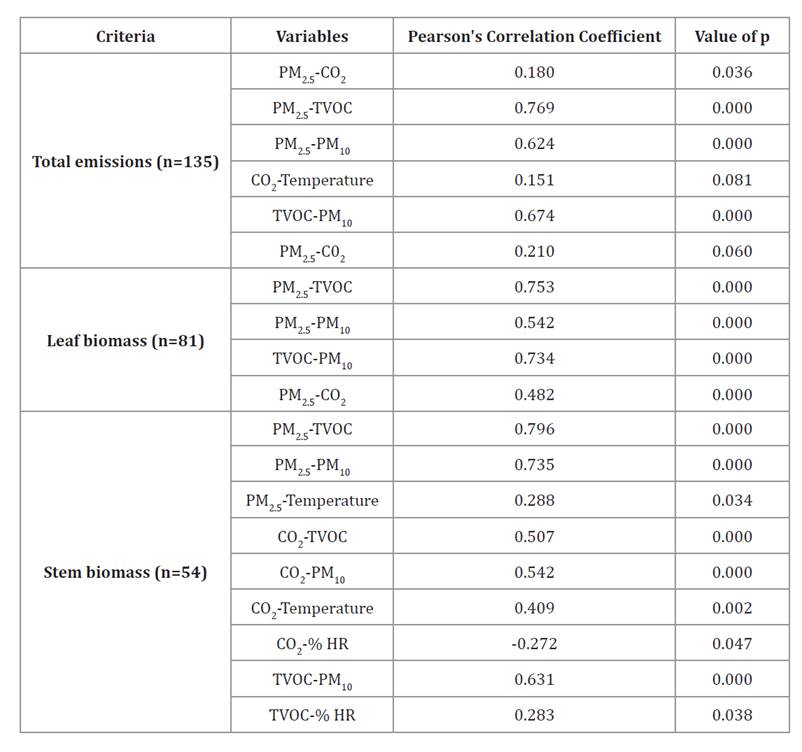

A significant Pearson correlation (p≤0.05) was detected between

gaseous emissions (CO₂, TVOC) and fine particles (PM2.5,

PM10) and

ambient conditions (relative humidity and air temperature). Additionally, the

Tukey test distinguished between total biomass emissions and emissions

generated by the pyrolysis of leaves and stems from the three species,

revealing pronounced differences at 200-400°C. On the other hand, principal

component analysis revealed the set of data (gases and particles) that explains

variation in incineration temperatures and species with higher or lower biomass

emissions. Regarding the Pearson correlation (table 2), the strongest

significant associations among the total emission variables were between PM2.5

and TVOC (r²=0.76) and between PM2.5 and PM10 (r²=0.62). Higher values

were observed for leaf biomass with PM2.5-TVOC

(r²=0.75) and TVOC-PM₁₀ (r²=0.73). Higher correlations were also observed for

leaf biomass with PM2.5-TVOC

and TVOC-PM10.

Ten significant correlations were identified in stem biomass; the strongest was

between PM2.5 and TVOC (r²=0.79).

Table 2. Results

of Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient on atmospheric variables in biomass

incineration (pyrolysis process) of three tree species (p≤0.05).

Tabla

2. Resultados del coeficiente de

correlación de Pearson en las variables atmosféricas de la incineración

(proceso de pirólisis) de biomasa de tres especies arbóreas (p≤0,05).

Total

Biomass Burning Emissions

An analysis of 181

samples revealed that incineration temperature, biomass origin (tree species),

and biomass type (leaf or stem) significantly affected total CO₂, PM2.5, PM₁₀, and TVOC

emissions (Tukey, p≤0.05). Considering the effect of incineration temperature

(50°C-450°C), physically bound moisture is removed at 20-120°C. Above 160°C,

chemically bound water is released through thermal condensation.

Between 120 and

150°C, the -H- and -C- bonds break, producing short-chain polymers that

condense within the pores. As the temperature increases to between 150 and

270°C, carbon dioxide (CO₂), carboxylic acids, phenol, furfural, methanol, and

other organic molecules are generated. This is primarily due to hemicellulose

depolymerization and the release of carbonyl and carboxyl groups from

cellulose. Lignin also overgoes reactions of aromatic rings in lignin (5,

13, 15, 16, 22, 23, 39). As the process progresses, the biomass darkens and begins to

resemble coal in terms of its properties. The most intense heat consumption and

mass loss occur in the early stages (13). According to

another technical source, volatile gases are released when the temperature of

dry biomass reaches 200°C-350°C during pyrolysis. These include carbon monoxide

(CO), carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄), and high-molecular-weight compounds

(tar), which condense into a liquid when cooled. These gases mix with oxygen in

the air and burn to produce a yellow flame. This self-sustaining process

involves heat from gas combustion, drying fresh fuel, and releasing additional

volatiles. Once all the volatiles have burned, the remaining solid is coal (44). Other

contributing factors include species-specific chemical compositions and

structural differences. For instance, a study of Schinus molle L.

essential oil identified nineteen compounds, with the major ones being

bicyclogermacrene, beta-caryophyllene, and spathulenol (37). As for P.

leavigata, different compounds have been found in its various organs,

including the fruit, leaves, and flowers. These compounds include phenolic

compounds and alkaloids, as well as the concentrations of 4-hydroxybenzoic

acid, p-coumaric acid, gallic acid, chlorogenic acid, cinnamic acid, and

p-coumaric acid (29). Studies on the

composition of A. farnesiana demonstrate that it essentially contains

terpenes, phenolic acids, flavonoids, tannins, alkaloids, fatty acids from seed

oils, polysaccharides, non-protein amino acids, and other phytochemicals (20).

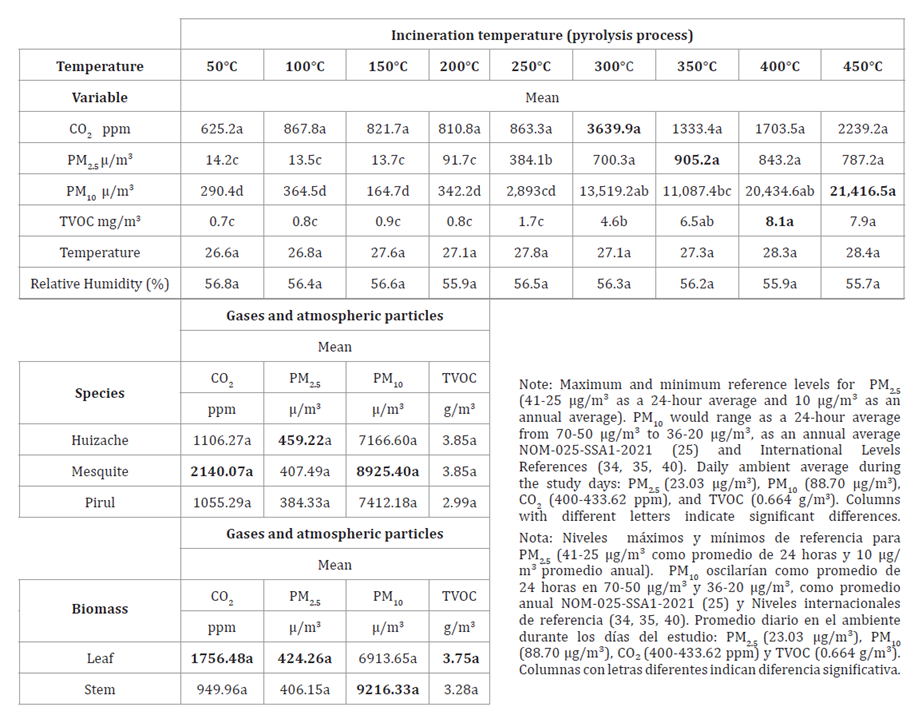

CO₂ emissions from the total biomass of the three species were

prioritized among the results because of their relevance as a greenhouse gas.

The CO₂ emissions data revealed that the highest mean value was reached at

300°C, with a difference of 3,014.7 ppm. The lowest emissions occurred at 50°C

(table

3).

Due to its biogenic origin, the CO₂ released during biomass combustion is

generally equivalent to the CO₂ absorbed during growth of trees, crops, and

other plant-based residues (8). CO₂ is a

greenhouse gas present in the global atmosphere at approximately 412 ppm, and

it is projected to increase (17). Using this

reference level, the emission measured in this study at 300°C (3,639.9 ppm)

exceeded the atmospheric reference by 8.83 times and the maximum average

reported for the study area by 8.39 times. Additionally, outdoor air typically

contains 300-400 ppm of CO₂ and can reach up to 550 ppm in urban areas (49).

Table 3. Ratio

of total gas emissions and total atmospheric particulate matter from biomass

burning of three tree species (Tukey, p≤0.05, n=135).

Tabla

3. Relación de emisiones totales de

gases y partículas atmosféricas totales de la quema de biomasa de tres especies

arbóreas (Tukey, p≤0,05, n=135).

Other studies

indicate that CO and CO₂ are primarily released at temperatures below 450°C and

exhibit similar patterns. Increasing the heating rate positively influences the

yield of combustible gases (46). At 450°C, PM10

emissions were higher, with an average of 21,416.5 μ/m³, compared

to an average of 21,251.8 μ/m³ from the incinerated biomass at 150°C. Mexico’s

NOM-025-SSA1-2021 establishes permissible PM10 concentration limits

maximum at 70 μg/m³, minimum at 50 μg/m³ (24-hour average) and 36 μg/m³ (annual

average) (25). Using the 24-hour criterion (70

μg/m³), the highest emission average over 24 hours was 892.25 μ/m³, and the

lowest was 6.86 μ/m³. At 450°C, PM₁₀ exceeded the 24-hour permissible limit by

a factor of 12.74, highlighting a significant environmental hazard. The value

of 892.25 μ/m³ was 10.05 times higher than the average recorded in the study

area during the experimental phase. Using the 24-hour criterion (50 μg/m³), the

highest emission average over 24 hour at 450°C, PM₁₀ exceeded the permissible

limit by a factor of 17.84 times. Elevated PM₁₀ levels have been linked to

adverse effects on plant physiological functions, including photosynthesis and

growth inhibition (36).

A study that burned

olive tree pruning waste and performed a chemical characterization estimated

average PM10 concentrations at 2,165

μg/m³, about fifty times higher than the PM10 concentrations estimated

at reference sites under normal conditions. These emissions were associated

with carbonaceous fractions, such as potassium (K), lead (Pb), and polycyclic

aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), as well as benzo(a)anthracene, benzo(a)pyrene,

and benzo(K)fluoranthene, for the biomass combustion source (10).

The highest PM2.5

emission, 905.2 μ/m³, was observed at 350°C, which is 891.7 μ/m³

higher than the average emission at 100°C. In accordance with NOM-025-SSA1-2021

(25), the maximum and

minimum permissible limits for PM2.5 are 41 μg/m³ and 25 μg/m³

(24-hour average) and 10 μg/m³ (annual average). In this context, the highest

recorded emission was 37.71 μg/m³ over a 24-hour period, not exceeding the

permissible limit of 41 μg/m³. This value was 39.30 times higher than those

recorded during the experimental days in the study area atmosphere. However,

with the minimum reference level (25μg/m³), this limit is 1.50 times higher. PM2.5

can originate from various sources and therefore exhibits

differences in chemical composition and physical characteristics. Common components

of PM2.5 include sulfates, black

carbon, nitrates, and ammonium. Sources of anthropogenic PM2.5 are mainly related to

combustion engines, industrial processes, power generation, burning coal and

wood, agricultural activities, and construction. Natural sources include dust

storms, forest fires, and sandstorms (35). On the other

hand, PM2.5 has been linked to toxic

levels of nickel (Ni), chromium (Cr), lead (Pb), arsenic (As), and black carbon

(BC). Its main sources of emission include coal combustion, industrial

activity, resuspended dust, and biomass burning. This indicates the urgent need

for control measures (32, 35). PM2.5 commonly contains

sulfates, black carbon, nitrates, and ammonium (35). According to the

U.S. Air Quality Index, PM2.5 concentrations over 250.5

μg/m³ pose a high risk to public health and the environment (34). In agricultural

areas, high levels of PM10 and PM2.5 have been reported,

reaching 800 μg/m³ and 485 μg/m³, respectively (57). Populations in

low- and middle-income countries are exposed to environmental PM2.5 levels between 1.3 and 4

times higher (31). While the

interspecific ratio of mean total emissions was not statistically significant, P.

laevigata emitted 1,084.78 ppm of CO₂, surpassing S. molle. Among the evaluated species, A. farnesiana

exhibited the highest PM2.5 emissions, surpassing S.

molle by 74.89 μg/m³. P. laevigata showed the highest levels of

PM₁₀, surpassing A. farnesiana by 1,758.8 μg/m³ (table 3). This highlights

notable interspecific variation in particulate emissions. The chemical analysis

of P. laevigata wood revealed that it contains 7.36% hemicellulose,

48.28% cellulose, 30.57% lignin, and 13.53% extractives (42).

Other studies on

the energy characterization of charcoal from species such as Prosopis have

found elements like magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), and

iron (Fe) in charcoal and ash. These studies reported a higher calorific value

of 27,669 kJ/kg for this species. These findings have been linked to particle

size distribution, moisture content, volatile material content, ash content,

fixed carbon content, and calorific value (23). Another key

finding was that total leaf biomass emitted higher levels of CO₂, PM2.5, and TVOC than

total stem biomass. Leaf emissions of CO₂ exceeded stem emissions by 806.52 ppm

across the three species. For PM2.5,

a difference of 18.11 μg/m³ was observed between leaf and stem emissions.

However, stem biomass emitted 2,302.68 μg/m³ more PM₁₀ than leaf biomass across

the three evaluated species (table 3). In both cases, the emission levels exceeded the limits set by

NOM-025-SSA1-2021 for PM₁₀, even when averaged over 24 hours (25).

The values obtained were higher than those measured in the

environment during the study (table 3). This result should consider that the area is influenced by

stone extraction, agricultural activities, and climatic factors that can cause

environmental variability, even though the experiment was conducted under

controlled conditions. The biomass’s biomolecular components are

lignocellulosic, comprising cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, which have

recognized potential for bioenergy systems (4,

22, 50). Some authors have studied biomass’ potential as a fuel source,

emphasizing the importance of the chemical composition of different plant

types. Processes such as torrefaction, in which biomass is heated to

temperatures between 200 and 300°C, can enhance its energy properties (18). PM2.5 emissions in Thailand

have been reported to range from 0 to over 4,001 milligrams per year,

considering contributions from agricultural residue burning, forest fires, and

open biomass burning (50). Factors

influencing particle numbers include tree species and combustion rate, which

reflect the materials’ slow-to-fast burning capacity, such as wood, leaves, and

branches (21, 54). The most prominent emission produced

during biomass combustion is CO₂, which serves as a proxy for the biomass

carbon content and as a principal greenhouse gas. Combustion efficiency is

often assessed based on the amount of carbon oxidized to CO₂. While biomass

generally contains about 45% carbon weight, coal typically contains over 60% (24,

26).

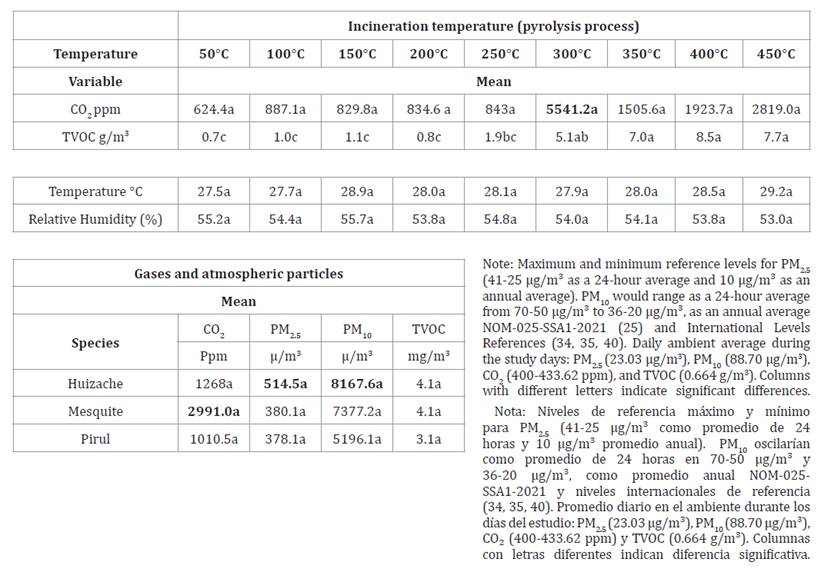

Leaf

Emissions of Three Tree Species

There was significant variation in gas and particle emissions

during the leaf BB for the three species (Tukey, p≤0.05). Table 3, shows that CO₂

emissions were higher at an incineration temperature of 300°C, with a

difference of 4916.8 ppm compared to the emissions reported at 50°C (5541.2

ppm). The maximum emission detected exceeds the atmospheric concentration of

512 ppm reported in technical documents by 13.44 times (17). The highest PM10

emission occurred at 450°C, at 22,910.8 μ/m³, showing a

significant difference of 22,683.4 μ/m³ relative to values at 150°C (figure 2B). In this case,

the estimated 24-hour average concentration was 954.61 μg/m³, which is 13.78

times higher than the 70 μg/m³ and 19.09 times higher than the 50 μg/m³

permissible limit established by the Mexican Official Standard

NOM-025-SSA1-2021 for this type of particulate matter (25). The highest

concentration of PM2.5 emissions was recorded at

350°C, reaching 869.1 μg/m³. This represents an 852.5 μg/m³ difference compared

to the 16.6 μg/m³ emission recorded at 150°C (figure 2A).

The

data shown refers to the mean ± standard error (different letters indicate significant

differences).

Los

datos representados refieren la media ± error estándar (letras diferentes

indican diferencia significativa).

Figure

2. Ratio of PM2.5 (A) and PM10 (B) emissions in leaves of three tree species

according to different incineration temperatures (Tukey, p≤0.05, n=81).

Figura

2. Relación emisiones de PM2.5 (A) y PM10 (B) en

hojas de tres especies arbóreas de acuerdo con las diferentes temperaturas de

incineración (Tukey, p≤0,05, n=81).

Based on this peak value, the estimated 24-hour average

concentration is 36.21 μg/m³, not exceeding the maximum limit of 41 μg/m³, but

if the minimum limit of 25 μg/m³ (1.39 times) established by NOM-025-SSA1-2021 (25). Table 4, shows atmospheric

gas and particle emissions from tree species of leafy biomass origin. P.

laevigata had higher CO₂ emissions, with a significant difference of

1,980.5 ppm compared to S. molle leaves. This difference is 4.8 times

higher than the reported average atmospheric concentration (412 ppm) (17). The leaves of A.

farnesiana emitted higher levels of PM2.5 and PM10 than those of the other

species. A. farnesiana had the highest PM10 emissions at 8,167.6

μ/m³, which is 4.86 times higher than the maximum limit (41 μ/m³) and 6.80

times minimum limit (50 μ/m³) established by NOM-025-SSA1-2021. The

corresponding 24-hour average would be 340.31 μ/m³. A pairwise comparison

between A. farnesiana and S. molle revealed that PM2.5

was 136.4 μ/m³ higher and PM10 was 2,971.5 μ/m³ higher

in A. farnesiana (table

4).

The highest PM2.5 value in A. farnesiana

(514.4 μ/m³) had a 24-hour average of 21.43 μ/m³, wich is well below the

limit specified in NOM-025-SSA1-2021 (25). Regarding the ash

generated from the total incinerated leaf biomass (g), S. molle was

significantly higher (0.444a) than A. farnesiana (0.349b) and P.

laevigata (0.294) (Tukey, p≤0.05).

Table 4. Ratio

of gas emissions and total atmospheric particulate matter from burning leaves

of three tree species (Tukey, p≤0.05, n=81).

Tabla

4. Relación de emisiones de gases y

partículas atmosféricas totales de la quema de hojas de tres especies arbóreas

(Tukey, p≤0,05, n=81).

Stem

Emissions of the Three Tree Species

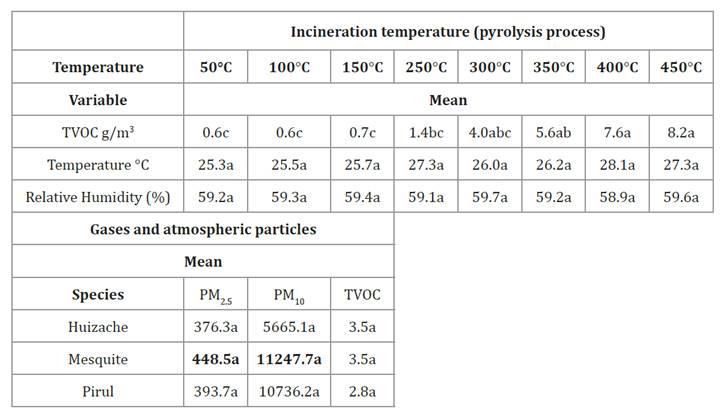

Table 5 (Tukey, p≤0.05)

shows significant differences in gas particle emissions from stem biomass. The

highest mean total volatile organic compound (TVOC) emission occurred between

300°C and 450°C, reaching 8.2 g/m³.

Table 5. Ratio

of gas emissions and total atmospheric particulate matter from the burning of

stems of three tree species (Tukey, p≤0.05, n=54).

Tabla

5. Relación de emisiones de gases y

partículas atmosféricas totales de la quema de tallos de tres especies arbóreas

(Tukey, p≤0,05, n=54).

The highest CO₂ emission was observed at 450°C, with a

concentration of 1,284.3 ppm. This represents a difference of 632.3 ppm

compared to the emission at 50°C. S. molle had the highest mean CO₂

emissions (1,122.4 ppm), which was 338.06 ppm higher than the remaining

species, such as mesquite (figure

3).

The

data shown refers to the mean ± standard error (different letters indicate

significant differences).

Los

datos representados refieren a la media ± error estándar (letras diferentes

indican diferencia significativa).

Figure

3. Ratio of CO₂ emissions (A) according to different

incineration temperatures and CO₂ (B) in related stems and the three species of

stem origin (Tukey, p≤0.05, n=81).

Figura

3. Relación emisiones de CO₂ (A) de

acuerdo con las diferentes temperaturas de incineración y CO₂ (B) en tallos en

relación con las tres especies de origen del tallo (Tukey, p≤0,05, n=81).

Based on S. molle’s emissions at 450°C, atmospheric CO₂

concentrations would be between 2.5 and 2.7 times the normal level (17). The highest PM10

emissions occurred at 400°C (26,787.8 μ/m³), differing in

26,710.4 μ/m³ relative to emissions at 150°C (figure 4).

The

data shown refers to the mean ± standard error (different letters indicate

significant differences).

Los

datos representados refieren a la media ± error estándar (letras diferentes

indican diferencia significativa).

Figure

4. Ratio of PM2.5 (A) and PM10 (B) emissions in the stems of three tree

species according to different incineration temperatures (Tukey, p≤0.05, n=81).

Figura

4. Relación de emisiones de PM2.5 (A) y PM10 (B) en

tallos de tres especies arbóreas de acuerdo con las diferentes temperaturas de

incineración (Tukey, p≤0,05, n=81).

Averaging this peak over 24 hours (1,116.15 μ/m³) shows that the

NOM-025-SSA1-2021 (25) standard is

exceeded by 15.94 times (maximum level 70 μ/m³) and 22.32 times (minimum level

50 μ/m³). As for PM2.5,

the highest emissions occurred between 300 and 400°C. The peak value was 997.5

μg/m³, representing a significant mean difference of 989.4 μg/m³ relative to

emissions at 50°C. This elevated emission would result in a 24-hour average

concentration of 41.56 μg/m³, which exceeds the NOM-025-SSA1-2021 limit by a

factor of 0.56 μg/m³, the maximum level of 41 μ/m³ and 1.66 times the minimum

level of 25 μ/m³ (25). The ratio of

residual ash to total biomass differed significantly among species in stem

samples. A. farnesiana had the highest ratio (0.427 g), followed by P.

laevigata (0.325 g) and S. molle (0.265 g), according to Tukey’s

test at p ≤ 0.05. Biomass burning causes a loss of organic matter and nutrients

from the soil through particle dispersion or volatilization. BB leads to the

loss of nutrients, soil biota, and total nitrogen (N) and carbon (C) in the

topsoil, and it promotes soil erosion. Although nutrients are retained in ash,

ash deposition increases the pH of the surface layer. The presence of ash

increases surface concentrations of Ca, Mg, K, Na, and P; however, the high

solubility of basic cations enhances leaching and promotes soil crusting (30).

Principal

Component Analysis

In the leaf-biomass dataset for the three tree species, the

first three components explained 74% of the variance (figure 5A, 5B; 6A, and 6B). PC1 explained

31% of the variance, PC2 explained 29.7%, and PC3 explained 14%. PC1 was driven

by % relative humidity (0.528), TVOC (0.316), PM2.5 (0.284), and dry weight

(-0.440). PC2 was mainly associated with TVOC (0.509), PM2.5 (0.478), PM10

(0.478), and ambient temperature (0.326). PC3 was primarily

defined by CO₂ (0.758), ash weight (-0.540), and dry weight (-0.250). In the

stem biomass analysis, the first three PCs explained 80% of the variance. PC1

was mainly driven by PM2.5 (0.505), PM10

(0.488), CO₂ (0.442), and TVOC (0.467). PC2 accounted for 27% of

the variance and had positive loadings on dry weight (0.535) and temperature

(0.454), as well as negative loadings on % relative humidity (-0.619) and TVOC

(-0.296).

Figure

5. Eigenvalues resulting from principal component

analysis of the emission of gases and atmospheric particles from burning leaves

of three tree species according to species (A) and incineration temperature

(B).

Figura

5. Distribución de eigenvalores

resultante del análisis de componentes principales de la emisión de gases y

partículas atmosféricas de la quema de hojas de tres especies arbóreas de

acuerdo con la especie (A) y la temperatura de incineración (B).

Figure

6. Eigenvalues resulting from the principal component

analysis of the emission of gases and atmospheric particles from the burning of

stems of three tree species according to species (A) and incineration

temperature (B).

Figura

6. Distribución de eigenvalores

resultante del análisis de componentes principales de la emisión de gases y

partículas atmosféricas de la quema de tallos de tres especies arbóreas de

acuerdo con la especie (A) y la temperatura de incineración (B).

These findings

revealed significant variation in emission behavior among biomass components,

likely driven by differences in the physicochemical structure of leaf and stem

tissues across the three evaluated tree species. This variability was also

evident across incineration temperatures from 50°C to 450°C, both in the

analysis of total biomass and within the leaf and stem fractions. This

criterion is important because most emissions are concentrated in the

respirable fraction of PM. Emission size distribution and chemical

characteristics vary with appliance type, combustion rate, fuel moisture, and

biomass type; therefore, measurement is required to comply with air quality

standards (2). Particulate

matter (PM) is a key indicator of air pollution levels. The type of PM and the

ratio between size particles (fine and coarse) determine its effects on human

health and atmospheric processes. PM is commonly classified as dust, mixed

aerosols, and anthropogenic aerosols (28). Another relevant

observation is that leaf biomass from S. molle had the highest ash

content (0.44 ± 0.03 g), and stem biomass from A. farnesiana produced

the most ash among stems (0.42±0.06 g). Residual ash can have further

environmental impacts. Its accumulation and the combustion of organic matter

can significantly alter soil properties. For example, burned soils have a

darker color, which results in lower albedo, increased environmental heat

absorption, and higher soil temperature (30).

Complete combustion

and open-air burning of residues require sufficient heat flux, an adequate

oxygen supply, and sufficient combustion time. The magnitude and composition of

emissions from this type of combustion depend on factors such as fuel density,

moisture content, topography (e.g., slope and terrain profile), and

meteorological conditions (e.g., wind and precipitation) (48). Emissions from

major contributors to atmospheric particulate matter (PM), especially the PM2.5

and PM10 fractions, have been

linked to biomass burning (BB), forest fires, agricultural residue burning, and

motor vehicles. These associations highlight challenges and inform policy

recommendations for improving air quality (50).

Burning biomass

fuels, especially wood-based ones, releases less CO₂ into the atmosphere than

burning coal (26). However, BB is a

major source of particulate matter and trace gases. Incomplete combustion

likely contributes to global warming, and its overall contribution to climate

change remains debated (9). Given the global

concern about air pollution, studies like this one can contribute not only to

our understanding of the impact of these reported levels on complex

environmental processes but also provide opportunities for integral

environmental improvements (35). Other studies

have linked PM10 emissions to phytotoxic

effects and elevated heavy metal concentrations (36). Additionally, BB

is a significant source of greenhouse gases (GHGs) and air pollutants (35). Another study

found that air pollutants generally impact plant species, causing

morphological, physiological, and biochemical damage (11).

In Mexico, anthropogenic emissions from stationary sources

account for 22.5% of PM10,

20.9% of PM2.5,

and 4.7% of VOCs. Area sources (pollutant sources that are too numerous and

dispersed to be classified as fixed sources) account for 73.0%, 73.3%, and 89%,

respectively. Mobile sources account for 4.5%, 5.8%, and 6.3%, respectively (47). The National Air

Strategy, under Axis 5 (Responsible and Participatory Society), seeks to

establish mechanisms for the community to understand air pollution impact and

actively participate in improving air quality. It is recognized that the most

commonly used solid fuels in Mexico are biomass, agricultural waste, and

primarily firewood, accounting for 80% of the energy consumed in rural

households (47). Therefore, it is

crucial to acknowledge the risks and impacts that the emissions and residues of

these gases and particles pose to public health and ecosystems. Evidence from

PM10 studies includes data on

indoor smoke dispersion among household members engaged in activities such as

cooking, doing chores, warming up by the stove, playing, resting, eating, and

sleeping. These studies demonstrated an exposure-response relationship, with a

higher rate of increase for daily exposures below 1,000–2,000 μg/m³ (27). Figure 7 shows how this

pilot experiment clarifies the interplay between environmental factors and

biomass intrinsic physicochemical characteristics (as in the three evaluated

species) and the behavior of biomass components (leaves and stems) during

pyrolysis across the laboratory-scale temperature range. The experiment also

evaluates atmospheric gases and particles for regulatory compliance and

highlights opportunities to extend the study to open field conditions and

incorporate additional variables of interest.

Figure

7. Summary of the main results of the study on

atmospheric emissions from tree species (own elaboration).

Figura

7. Resumen de los principales

resultados del estudio sobre las emisiones atmosféricas de las especies

arbóreas (elaboración propia).

Conclusions

This study experimentally verified the environmental impacts of

biomass burning for three tree species under a laboratory pyrolysis process.

The emissions of PM2.5,

PM10, CO₂, and

total and specific VOCs varied between leaves and stems. This likely reflects

the anatomical and physicochemical differences in the biomass that affect

combustion at different incineration temperatures (50°C to 450°C). The highest

PM2.5 and PM10 emissions occurred in A.

farnesiana leaves and in P. laevigata stems. The order of highest

CO₂ emissions in leaves was P. laevigata > A. farnesiana > S.

molle; in stems, it was S. molle > A. farnesiana > P.

laevigata. The PM2.5,

PM10, and CO₂

levels observed in this study exceeded the limits established by Mexican and

international air quality regulations. CO₂ levels exceeded the technical

reference for atmospheric averages (412 ppm) by 8.83 times and the average

level in the study area by 8.39 times. PM₁₀ exceeded the limit allowed by

Mexican environmental regulations and international references (e.g.,

the World Health Organization) by 12.74 times (maximum level) and 17.84 times

the minimum level, as well as the level in the environment adjacent to the

study area by 10.05 times. Similarly, the level of PM2.5 does not exceed the

permitted 24-hour maximum limit. However, with the minimum reference level,

this limit is 1.50 times higher. The biomass emissions were 39.30 times higher

than those measured in the area surrounding the study site. These elevated

concentrations pose significant environmental risks and potential public health

impacts. They can also harm ecosystems, including phytotoxic effects on plants

and broader environmental degradation. Future studies should evaluate

differences in residual ash quantities and compare biomass burning technologies

and processes, as these differences may introduce additional environmental

impacts. Experimental limitations include the need to standardize the mass of

biomass and the size of samples when comparing materials such as leaves and

stems. This is where variables such as fresh weight, dry weight, and moisture

content are critical. To obtain more reliable results across samples,

especially when comparing laboratory and field emissions, environmental

conditions (temperature, humidity, wind speed, and solar radiation) and proper

instrument calibration must also be considered. These results can inform

assessments of the environmental impacts of using plants as an energy source

and support the integration of additional environmental variables into future

research and air pollution monitoring programs. Further comparisons across

biomass burning sources and processes should strengthen evaluations of

environmental impact considering air pollution.

1. Aguiar, S.;

Enríquez Estrella, M.; Uvidia Cabadiana H. 2022. Residuos agroindustriales: su

impacto, manejo y aprovechamiento. AXIOMA. 1(27): 5-11.

https://doi.org/10.26621/ra.v1i27.803

2. Air Quality

Expert Group. 2017. The Potential Air Quality Impacts from Biomass Combustion.

https://uk-air.defra.gov.uk/assets/documents/reports/cat11/1708081027_170807_

AQEG_Biomass_report.pdf%20

3. Alcalá Jáuregui,

J.; García Arreola, M. E.; Rodríguez Ortiz, J. C.; Beltrán Morales, F. A.;

Villaseñor Zuñiga, M. E.; Rodríguez Fuentes, H.; Hernández Montoya, A. 2013.

Vegetación bioindicadora de metales pesados en un sistema semiárido. Revista de

la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza.

Argentina. 45(1): 27-42.

4. Alcalá Jáuregui,

J.; Rodríguez Ortíz, J. C.; Hernández Montoya, A.; Filippini, M. F.; Martínez

Carretero, E.; Diaz Flores, P. E. 2018a. Capacity of two vegetative species of

heavy metal accumulation. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias.

Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 50(1): 123-139.

5. Alcalá Jáuregui,

J.; Rodríguez Ortiz, J. C.; Hernández Montoya, A.; Filippini, M. F.; Martínez

Carretero, E.; Díaz Flores, P. E.; Rojas Velázquez, A. N.; Rodríguez-Fuentes,

H.; Beltrán Morales, F. A. 2018b. Heavy metals in atmospheric dust deposited in

leaves of Acacia farnesiana (Fabaceae) and Prosopis laevigata (Fabaceae).

Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo.

Mendoza. Argentina. 50(2): 173-185.

6. Alcalá Jáuregui, J.; Rodríguez Ortiz, J. C.; Filippini, M.

F.; Martínez Carretero, E.; Hernández Montoya, A.; Rojas Velázquez, Á. N.;

Méndez Cortés, H.; Beltrán Morales, Felix A. 2022. Metallic elements in foliar

material and fruits of three tree species as bioindicators. Revista de la Facultad

de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 54(2):

61-72. https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.083

7. Alcalá Jáuregui,

J. A.; Ochoa Arriaga, A.; Martínez Carretero, E.; Navas Romero, A.; Ontivero,

M.; Filippini, M. F.; Rojas Velázquez, A. N.; Guillén Castillo, O. I.; Lara

Izaguirre, A. Y.; Duplancic, A.; Villegas Rodríguez, F. 2024. Evaluación de

emisiones de CO2 y

partículas finas en la incineración de biomasa de calabacita (Cucurbita pepo

L.-Cucurbitaceae). Multequina 33: 105-120.

http://id.caicyt.gov.ar/ark:/s18527329/wviayjl94

8. Ali, F., Dawood,

A.; Hussain, A.; Alnasir, M. H.; Khan, M. A.; Butt, T. M.; Janjua, N. K.;

Hamid, A. (2024). Fueling the future: biomass applications for green and

sustainable energy. Discover Sustainability.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00309-z

9. Almsatar, T.

2020. Environmental Issues of Biomass-Burning in Sub-Saharan African Countries.

In: Mammino, L. (eds). Biomass Burning in Sub-Saharan Africa. Springer.

https:// doi. org/10.1007/978-94-007-0808-2_1

10. Amodio, M.;

Andriani, E.; Dambruoso, P.; Daresta, B.; de Gennaro, G.; Gilio, A.; 2012.

Impact of biomass burning on PM10 concentrations. Fresenius Environ.

Bull. 21: 3296-3300.

11. Anand, P.;

Mina, U.; Khare, M.; Kumar, P.; Kota, S. H. 2022. Air pollution and plant

health response-current status and future directions. Atmospheric Pollution

Research. 13(6): 101508. DOI: 10.1016/j.apr.2022.101508

12. Arteaga, J.;

Arenas, E.; López, D.; Sanchéz, C.; Zapata, Z. 2012. De la pirólisis rápida de

residuos de palma africana (Elaeis guineensis Jacq). Biotecnología en el

Sector Agropecuario y Agroindustrial. 10(2): 144-151.

http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/bsaa/v10n2/ v10n2a17.pdf

13. Arteaga-Pérez,

L. E.; Segura, C.; Santana, K. D. 2016. Procesos de torrefacción para

valorización de residuos lignocelulósicos. Análisis de posibles tecnologías de

aplicación en Sudamérica. Afinidad. 73(573).

14. Baray, M. del

R. 2016. Pirólisis a abaja temperatura en materiales avanzados de la pomasa de

manzana para la producción de biocombustibles. Centro de Investigación en

Materiales Avanzados.

https://cimav.repositorioinstitucional.mx/jspui/handle/1004/363

15. Basu, P.;

Sadhukhan, A. K.; Gupta, P.; Rao, S.; Dhungana, A.; Acharya, B. 2014. An

experimental and theoretical investigation on torrefaction of a large wet wood

particle. Bioresource technology. 159: 215-222.

16. Bergman, P. C.

2005. Combined torrefaction and pelletisation. The TOP process. ECN-C-05-073.

17. Buis, A. 2019.

The Atmosphere: Getting a Handle on Carbon Dioxide-Climate Change: Vital Signs

of the Planet. Retrieved December 6, 2020. https:// climate.nasa.gov/news/2915/

the-atmospheregetting-a-handle-on-carbon-dioxide/

18. Bustamante

García, V.; Carrillo Parra, A.; Prieto Ruíz, J. A.; Corral-Rivas, J. J.;

Hernández Díaz, J. C. 2016. Química de la biomasa vegetal y su efecto en el

rendimiento durante la torrefacción: Revisión. Revista mexicana de Ciencias

Forestales. 7(38): 5-23. http://www.scielo.org. mx/

scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2007-11322016000600005&lng=es&tlng=es.

19. Chang, D.; Li,

Q.; Wang, Z.; Dai, J.; Fu, X.; Guo, J.; Zhu, L.; Pu, D.; Cuevas, C. A.;

Fernandez, R. P.; Wang, W.; Ge, M.; Fung, J. C. H.; Lau, A. K. H.; Granier, C.;

Brasseur, G.; Pozzer, A.; Saiz-Lopez, A.; Song, Y.; Wang, T. 2024. Significant

chlorine emissions from biomass burning affect the long-term atmospheric

chemistry in Asia. National Science Review. 11(9): nwae285. https://doi.

org/10.1093/nsr/nwae28520

20. Chekchaki, S.;

Zaafour, M. D.; Chekchaki, N. 2025. Acacia farnesiana (L.) Willd:

Ecology, uses and phytochemical composition. African Journal of Biological

Sciences. 7(4): 547-566. https:// doi.org/10.48047/AFJBS.7.4.2025.547-566

21. Chen, J.; Li,

C.; Ristovski, Z.; Milic, A.; Gu, Y.; Islam, M. S.; Wang, S.; Hao, J.; Zhang,

H.; He, C.; Guo, H.; Fu, H.; Miljevic, B.; Morawska, L.; Thai, P.; LAM, Y. F.;

Pereira, G.; Ding, A.; Huang, X.; Dumka, U. C. 2017. A review of biomass

burning: Emissions and impacts on air quality, health and climate in China.

Science of the Total Environment. 579: 1000-1034. https:// doi.

org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.11.025

22. Chuetor, S.;

Panakkal, E. J.; Ruensodsai, T.; Cheenkachorn, K.; Kirdponpattara, S.; Cheng,

Y. S.; Sriariyanun, M. 2022. Improvement of Enzymatic Saccharification and

Ethanol Production from Rice Straw Using Recycled Ionic Liquid: The Effect of

Anti-Solvent Mixture. Bioengineering. 9(3): 115.

https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering9030115

23. Cruz

Montelongo, C.; Herrera Gamboa, J.; Ortiz Sánchez, I.; Ríos Saucedo, J. C.;

Rosales Serna, R.; Carrillo-Parra, A. 2020. Caracterización energética del

carbón vegetal producido en el Norte-Centro de México. Madera y bosques. 26(2):

e2621971. https://doi.org/10.21829/ myb.2020.2621971

24. Demirbas, A.

2004. Combustion characteristics of different biomass fuels. Progress in

energyand combustion science. 30(2): 219-230.

25. Diario Oficial

de la Federación. 2021. NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM-021-SSA1-2021. Salud

ambiental. Valores límite permisibles para la

concentración de partículas suspendidas PM10 y PM2.5 en el aire, ambiente y

criterios para su evaluación. https://rama.edomex. gob.

mx/sites/rama.edomex.gob.mx/files/files/NOM-025-SSA1-2021.pdf%20

26. Dula, M.;

Kraszkiewicz, A. 2025. Theory and Practice of Burning Solid Biofuels in

Low-Power Heating Devices. Energies. 18(1): 182.

https://doi.org/10.3390/en18010182

27. Ezzati, M.; Kammen, D. M. 2002. The health impacts of

exposure to indoor air pollution from solid fuels in developing countries:

Comprehension, gaps, and data needs. Environ Health Perspect. 110(11): 1057-68.

https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.021101057

28. Fan, H.; Zhao,

C.; Yang, Y.; Yang, X. 2021. Spatio-Temporal Variations of the PM2.5/PM10

Ratios and Its Application to Air Pollution Type Classification

in China. Front. Environ. Sci. 9: 692440. DOI: 10.3389/fenvs.2021.692440

29.

García-Azpeitia, L.; Montalvo-González, E.; Loza-Cornejo, S. 2022.

Caracterización nutricional y fitoquímica de hojas, flor y fruto de Prosopis

laevigata. Botanical Sciences. 100(4): 1014-1024.

30. Grillo, G.;

Tabasso, S.; Cravotto, G.; van Ree, T. 2020. Burning Biomass: Environmental

Impact on the Soil. In: Mammino, L. (eds) Biomass Burning in Sub-Saharan

Africa. Springer. https://doi. org/10.1007/978-94-007-0808-2_2

31. Health Efects

Institute. 2024. State of Global Air 2024. Special Report.

32. Hua, C.; Ma,

W.; Zheng, F.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, J.; Ma, L.; Song, B.; Yan, C.; Li, H.; Liu, Z.;

Liu, Q.; Kulmala, M.; Liu, Y. 2024. Health risks and sources of trace elements

and black carbon in PM2.5 from 2019 to 2021 in

Beijing. Journal of Environmental Sciences. 142: 69-82. https://doi.

org/10.1016/j.jes.2023.05.023

33. IFC.

International Finance Corporation. 2017. Converting Biomass to Energy: A Guide

for Developers and Investors.

34. IQAir. Air

Visual. 2018. 2018 World Air Quality Report. Region & City PM2.5

Ranking. Region & City PM2.5 Ranking.

https://www.iqair.com/ dl/2018_world-air-quality-report-2018-en.pdf

35. IQAir. Air

Visual. 2023. 2023 World Air Quality. Region and City PM2.5 Ranking.

https://www.iqair. com/

dl/2023_World_Air_Quality_Report.pdf%20

36.

Moscoso-Vanegas, D.; Monroy-Morocho, L.; Narváez-Vera, M.; Espinoza-Molina, C.;

Astudillo- Alemán, A. 2019. Efecto fitotóxico del metraila particulado PM10

recolectado en el área urbana de la Ciudad de Cuenca, Ecuador.

Iteckne. 16(1): 12-20. https://doi.org/10.15332/ iteckne.v16i1.2157

37. Muhd, P. S. D.;

Cuelho, C. H. F.; Brondani, J. C.; Manfron, M. P. 2015. Chemical composition of

the Schinus molle L. essential oil and their biological activities.

Revista Cubana de Farmacia. 49(1): 132-143.

38. Naciones

Unidas. 2018. La Agenda 2030 y los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible: una

oportunidad para América Latina y el Caribe. LC/G.2681-P/Rev.3.

39. Nhuchhen, D.

R.; Basu, P.; Acharya, B. 2014. A comprehensive review on biomass torrefaction.

Int. J. Renew. Energy Biofuels. 1-56.

40. Organización

Mundial de la Salud. 2021. Directrices mundiales de la OMS sobre la calidad del

aire: materia particulada (MP2.5 y

MP10), ozono, dióxido

de nitrógeno, dióxido de azufre y monóxido de carbono: resumen ejecutivo.

Organización Mundial de la Salud. https://iris. who.int/handle/10665/346062.

41. Pinakana, S.

D.; Raysoni, A. U.; Sayeed, A.; Gonzalez, J. L.; Temby, O.; Wladyka, D.;

Sepielak, K.; Gupta, P. 2024. Review of Agricultural Biomass Burning and its

Impact on Air Quality in the Continental United States of America.

Environmental Advances. Vol.: 16. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.envadv.2024.100546

42. Pintor-Ibarra,

L. F.; Alvarado-Flores, J. J.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, J. G.; Alcaraz-Vera, J. V.;

Ávalos-Rodríguez, M. L.; Moreno-Anguiano, O. 2024. Chemical and Energetic

Characterization of the Wood of Prosopis laevigata: Chemical and Thermogravimetric

Methods. Molecules. 29(11): 2587. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112587

43. Reinhardt, T.

E.; Ottmar, R. D.; Castilla, C. 2001. Smoke impacts from agricultural burning

in a rural Brazilian town. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association

(1995). 51(3): 443-450. https://doi.org/10.1080/10473289.2001.10464280

44. Sadaka, S.;

Johnson, D. M. 2011. Biomass Combustion. Cooperative Extension Service.

University of Arkansas. US Department of Agriculture and county governments

cooperating. FSA1056.

45. Saleem M. 2022.

Possibility of utilizing agriculture biomass as a renewable and sustainable

future energy source. Heliyon. 8(2): e08905.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08905

46. Sangaré, D.;

Belandria, V.; Bostyn, S.; Moscosa-Santillan, M.; Gökalp, I. 2024.

Pyro-gasification of lignocellulosic biomass: online quantification of gas

evolution with temperature, effects of heating rate, and stoichiometric ratio.

Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery. 14(8): 9763-9775.

47. Secretaría de

Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. 2016. Estrategia Nacional de Calidad del

Aire. ENCA. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/195809/Estrategia_

Nacional_Calidad_del_Aire.pdf%20

48. Sivertsen, B.

2006. Air pollution impacts from open air burning. WIT Transactions on Ecology

and the Environment. 92.

49. Subils, M. J.

B.; Domínguez, F. B. 2000. NTP 549: El dióxido de carbono en la evaluación de

la calidad del aire interior. España: Centro Nacional de Condiciones de

Trabajo. 124p.

50. Suriyawong, P.; Chuetor, S.; Samae, H.; Piriyakarnsakul, S.;

Amin, M.; Furuuchi, M.; Hata, M.; Inerb, M.; Phairuang, W. 2023. Airborne

particulate matter from biomass burning in Thailand: Recent issues, challenges,

and options. Heliyon. 9(3): e14261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

heliyon.2023.e14261

51. Torres-Duque,

C.; Maldonado, D.; Pérez-Padilla, R.; Ezzati, M.; Viegi, G. 2008. Forum of

International Respiratory Studies (FIRS) Task Force on Health Effects of

Biomass Exposure. Biomass fuels and respiratory diseases: A review of the

evidence. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 5(5): 577-590.

https://doi.org/10.1513/pats.200707-100RP

52. Tripathi, S.;

Yadav, S.; Sharma, K. 2024. Air pollution from biomass burning in India.

Environ Res Lett. 19:073007. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ad4a90

53. Valencia, G.

M.; Anaya, J. A.; Caro-Lopera, F. J. 2022. Bottom-up estimates of atmospheric

emissions of CO2,

NO2, CO, NH3, and Black Carbon,

generated by biomass burning in the north of South America. Revista de Teledetección.

59: 23-47. https://doi.org/10.4995/raet.2021.15594

54. Wardoyo, A. Y.;

Morawska, L.; Ristovski, Z. D.; Marsh, J. 2006. Quantifcation of particle

number and mass emission factors from combustion of Queensland trees. Environ.

Sci. Technol. 40(18): 5696-5703.

55. WHO. 2023. Who

Ambient Air Quality Database, 2022 update: status report. https://www.who. int/publications/i/item/9789240047693

56. WHO. 2024.

Ambient (outdoor) air pollution. https://www.who.int/ news-room/fact-sheets/

detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health%20//%20

57. Wu, Y.; Han,

Y.; Voulgarakis, A.; Wang, T.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Xie, M.; Zhuang, B.; Li, S.

2017. An agricultural biomass burning episode in eastern China: Transport,

optical properties, and impacts on regional air quality, J. Geophys. Res.

Atmos. 122: 2304-2324. DOI: 10.1002/2016JD025319

58. Zauli-Sajani, S.; Thunis, P.; Pisoni, E.; Bessagnet, B.;

Monforti-Ferrario, F.; De Meij, A.; Pekar, F.; Vignati, E. 2024. Reducing

biomass burning is key to decrease PM2.5 exposure in European

cities. Scientific reports. 14(1): 10210.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60946-2