Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias

Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Tomo 57(2). ISSN (en línea) 1853-8665.

Año 2025.

Original article

Strategic

Pathways for the Olive Oil Chain in Argentina: Profitability, Sustainability

and Oleo tourism

Rutas

estratégicas para la cadena de aceite de oliva en Argentina: rentabilidad,

sostenibilidad y oleoturismo

Alejandro Juan

Gennari1,

Vanina Fabiana

Ciardullo1,

Leonardo Javier

Santoni1

1Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias.

Cátedra de Economía y Política Agraria. Almirante Brown 500. M5528AHB. Chacras

de Coria. Mendoza. Argentina.

*pwinter@fca.uncu.edu.ar

Abstract

The olive oil

agri-food chain in Argentina is strategically relevant for rural development,

employment, exports and tourism. Despite quality production and industrial

capacity, the sector faces structural problems: high labour and energy costs,

limited domestic consumption, and dependence on subsidized international

competitors. This study analyses the chain using multicriteria programming

across five dimensions: productive, economic-financial, commercial,

environmental and tourism-territorial. The baseline was built from data

collected between 2018 and 2024 (Agricultural Census 2018, official reports and

international benchmarks), covering the country’s most representative producing

regions (Catamarca, La Rioja, San Juan and Mendoza), which together account for

over 90% of national output. Results from scenario simulations reveal

trade-offs: export-oriented strategies maximize profit but increase

vulnerability to global prices; internal consumption growth strengthens resilience

yet moderates revenues; environmental sustainability improves efficiency

through lower water use; and balanced development with olive oil tourism

achieves robust outcomes across all dimensions. A novel contribution is the

quantitative inclusion of tourism, showing its potential to generate rural

employment and enhance brand value. The findings support forward-looking

strategies that combine technological reconversion, market diversification,

efficient resource use and tourism integration, offering policy guidelines for

sustainable territorial development.

Keywords: olive oil supply

chain, costs, competitiveness, sustainability, bioeconomy, tourism, Argentina

Resumen

La cadena

agroalimentaria del aceite de oliva en Argentina es estratégica para el

desarrollo rural, el empleo, las exportaciones y el turismo. A pesar de su

calidad productiva y capacidad industrial, el sector enfrenta problemas

estructurales: altos costos laborales y energéticos, bajo consumo interno y

dependencia de competidores internacionales subsidiados. Este estudio analiza

la cadena mediante programación multicriterio en cinco dimensiones: productiva,

económico-financiera, comercial, ambiental y turística-territorial. El

escenario base se construyó con datos relevados entre 2018 y 2024 (Censo

Agropecuario 2018, informes oficiales y referencias internacionales), abarcando

las provincias más representativas (Catamarca, La Rioja, San Juan y Mendoza), que

concentran más del 90% de la producción nacional. Los resultados de las

simulaciones por escenarios evidencian compensaciones: las estrategias

orientadas a la exportación maximizan beneficios pero aumentan la

vulnerabilidad a precios globales; el desarrollo del consumo interno fortalece

la resiliencia aunque reduce ingresos; la sostenibilidad ambiental mejora la

eficiencia al reducir uso de agua; y un desarrollo equilibrado con oleoturismo

logra resultados robustos en todas las dimensiones. El aporte novedoso es la

incorporación cuantitativa del turismo, que muestra su potencial para generar

empleo rural y valor de marca. Los hallazgos sustentan estrategias prospectivas

que combinan reconversión tecnológica, diversificación de mercados, uso

eficiente de recursos e integración turística, ofreciendo lineamientos para

políticas públicas y desarrollo sustentable.

Palabras clave: cadena de valor del

aceite de oliva, costos, competitividad, sustentabilidad, bioeconomía, turismo,

Argentina

Originales: Recepción: 28/07/2025 - Aceptación: 08/10/2025

Introduction

Argentina’s olive

oil sector holds strategic relevance not only for its product but also for its

role in rural development, employment, and the diversification of semi-arid

territories. Extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) from Argentina has achieved

international recognition for quality (Benencia et al., 2014), supported by

industrial capacity and technological advancement. However, the sector faces

persistent structural problems: high labour and energy costs compared to

competitors (Ministerio

de Economía, 2024), strong dependence on subsidized producers such as Spain and

Italy, and limited domestic demand (CREA, 2021). These factors

have hindered competitiveness and limited the capacity to capture value at

national level. Argentina ranks 10th worldwide in olive oil

production, with annual outputs fluctuating between 28,000 and 36,000 tons in

peak years (IOC,

n. d.; Ministerio de Economía, 2024). The sector employs around 30,000 temporary rural workers,

equivalent to nearly three million daily wages per year (CREA,

2021),

representing 8.1% of the national agricultural labour requirement. Despite this

production capacity, domestic consumption remains extremely low (180-250 cc per

capita annually), far below Mediterranean standards (Spain: ~15 litters per

capita). This imbalance highlights a major challenge: while Argentina has

structural potential, it captures limited value internally, depending heavily

on exports and leaving domestic demand underdeveloped. These structural

conditions justify the need for a comprehensive approach that analyses the

chain not only in economic terms but also through its productive, commercial,

environmental and territorial dimensions. Beyond its productive dimension, the

olive oil chain must be understood as a networked agri-food system, where

interdependencies extend to logistics, marketing, tourism and environmental

management (García-Cascales

et al., 2021). This broader view enables policies to shift from a narrow

“sectoral plan” to a flexible “roadmap” capable of adapting to disruptive

changes in technology, trade and regulations (Romero, 1993). Moreover, the

concept of bioeconomy reinforces this approach: olive cultivation generates

biomass, by-products and ecosystem services whose valorisation expands the

economic and territorial impacts (Stark et al., 2021). The present

study therefore adopts an integrated five-dimension perspective: (i) productive

efficiency, (ii) economic-financial profitability, (iii) logistics and

commercialization, (iv) environmental sustainability, and (v) tourism and

territorial valorisation. This framework moves beyond isolated analysis of

costs or yields, proposing instead a systemic evaluation of Argentina’s olive

oil chain as both a production network and a driver of local development. The

research is guided by the following objectives:

(a) analyse the

chain’s structure and bottlenecks.

(b) simulate

scenarios of value creation through multicriteria programming; and

(c) evaluate

trade-offs between profitability, sustainability, domestic demand and oleo

tourism.

The central

hypothesis is that multicriteria programming can identify optimal strategic

pathways for the olive oil chain in western Argentina, showing that a balanced

approach integrating technological reconversion, sustainability and tourism

improve resilience and competitiveness compared to purely export-oriented

strategies. The analysis focuses on Argentina’s main producing provinces

(Catamarca, La Rioja, San Juan and Mendoza), which together account for over

90% of national olive oil output. While the baseline data correspond to

2018-2024, the scenarios are prospective, designed to explore strategic

pathways for the future of the sector.

Materials

and Methods

Methodological

Approach: Multicriteria Linear Programming (MCP)

The methodological

framework chosen was Multicriteria Linear Programming (MCP), as it enables the

simultaneous evaluation of multiple, and often conflicting, objectives relevant

to the olive oil value chain. This approach goes beyond single-objective

optimization by capturing trade-offs between profitability, production, market

allocation, environmental impacts and tourism valorisation. The focus of this

study is not on statistical sampling, but on the integration of aggregated data

from national censuses, official sectoral reports and international benchmarks.

In this sense, concepts such as “sample” or “survey” are not applicable, since

the analysis is systemic and chain oriented. The model is structured across five

dimensions -productive, economic-financial, commercial, environmental, and

tourism-territorial- which together reflect the sustainability and strategic

development goals of the sector. Within this framework, MCP was applied to

determine the optimal allocation of land, production, investments and market

shares under real-world constraints. The method allows the generation of

Pareto-efficient solutions, making visible the compromises between objectives

and enabling the design of alternative strategic scenarios. This orientation

provides a rigorous yet flexible analytical tool, adaptable not only to olive

oil but also to other perennial crop systems embedded in similar ecological and

territorial contexts (García-Cascales et al, 2021; Romero, 1993).

Justification

of Multicriteria Programming (MCP vs. MCDM)

The choice of

Multicriteria Linear Programming (MCP) is justified by the complexity of the

olive oil value chain, where multiple and often conflicting objectives must be

considered simultaneously. Traditional single-objective models fail to capture

trade-offs between profitability, domestic consumption, exports, environmental

impact and tourism valorisation. MCP provides a quantitative framework that

integrates these dimensions and generates optimal solutions under real-world

constraints. It is important to distinguish MCP from Multicriteria Decision

Making (MCDM) approaches: while MCDM is designed to select among a finite set

of alternatives (qualitative decision-making), MCP allows continuous

optimization of resource allocation across multiple objectives. This

distinction is relevant because the study does not evaluate pre-defined options

but rather allocates hectares, production volumes and investments dynamically,

reflecting real strategic planning needs.

The capacity of MCP to explore Pareto-efficient solutions and

identify trade-offs among objectives strengthens its applicability to agri-food

systems embedded in uncertain international markets and resource constraints (García-Cascales

et al, 2021; Romero, 1993).

Data

Collection and Update

Data consolidation

was carried out by integrating official and sectoral sources rather than

through statistical sampling. The structural base was provided by the 2018

National Agricultural Census (INDEC, 2019), complemented

with annual sectoral reports from the Ministerio de Economía (2024),

CREA (2021), and international benchmarks (IOC, 2015). Production

volumes, costs and yields were compiled from these sources, covering the four

main olive-producing provinces (Catamarca, La Rioja, San Juan, Mendoza). Given

Argentina’s inflationary context, all values were expressed in constant U.S.

dollars, updated through official price indices. This procedure ensured

comparability with international cost studies and positioned Argentina in a

medium-to-high cost range relative to major competitors such as Spain and Portugal.

As a result, the estimated average cost of a 500 ml bottle of olive oil was

US$3.26, distributed as 50% primary production, 19% industrial processing and

31% packaging and fractionation. This calculation does not stem from a

statistical survey but from sector-wide structural data, reflecting the

systemic focus of chain analysis. Therefore, terms like “sample” or “survey”

are not applicable: the analysis is based on censual and aggregated information

integrated into the programming model income. From a bioeconomy perspective,

olive cultivation also generates by-products such as pomace, pits, leaves, and

pruning residues. These can be valorised through energy (biofuels, pellets),

compost and soil amendments, animal feed, as well as tourism and ecosystem services.

Although not explicitly included as decision variables in the model, these

alternatives were acknowledged as part of the conceptual framework.

Continuous

Decision Variables

The following

decision variables capture the strategic choices available to the olive oil

chain. They are associated mainly with the productive, commercial and tourism

dimensions, representing cultivated hectares, production volumes, market

allocation, and visitor flows. These variables are optimized by the model to

explore alternative scenarios and resource allocation strategies.

• Htrad:

Hectares in production of traditional olive groves (ha).

• Hint:

Hectares in production of intensive olive groves (ha).

• Qtrad:

Olive oil production obtained from traditional systems (ton).

• Qint:

Olive oil production obtained from intensive systems (ton).

• E: Volume of

olive oil destined for export (ton).

• D: Volume of

olive oil destined for the domestic market (ton).

• M: Investment in

marketing and promotion for the domestic market (millions of USD).

• Ti:

Number of tourists visiting province i (persons), quantifying olive oil tourism

activity in each region.

• Ii:

Investment in tourism infrastructure and promotion in province i (millions of

USD), reflecting strategic capital allocation for tourism development.

• (Horg):

Hectares under organic certification (optional, if a specific organic

production objective is modelled).

Parameters

(Fixed by Scenario or Context):

The parameters

correspond to fixed or contextual values that condition the system. They

include aspects of the productive dimension (yields, water and energy use), the

economic-financial dimension (costs, prices, taxes), the environmental dimension

(emission coefficients, water limits), and the tourism-territorial dimension

(capacity, income per visitor). By defining these constants, the model ensures

comparability across scenarios and consistency with official and international

data sources.

rtrad, rint:

Oil yield per hectare (ton/ha) for traditional and intensive systems,

respectively (e.g., rtrad=0.5,

rint=1.5

ton/ha).

αtrad, αint:

Water requirement per hectare (m³/ha) for traditional and intensive systems

(e.g., αtrad=3000, αint=5000).

βtrad, βint:

Energy consumption per hectare (kWh/ha) for traditional and intensive systems

(e.g., βtrad=50, βint=200).

Pexp,

Pdom: Price

per ton of oil in the export and domestic market (e.g., Pexp=4000,

Pdom=3500

USD/ton).

texp: Export tax rate (decimal, e.g.,

texp=0.05).

ctrad, cint:

Total cost per ton of oil produced in each system (e.g., ctrad=3800,

cint=2300

USD/ton).

Cmkt:

Marketing cost per ton for the domestic market (e.g., Cmkt=500

USD/ton).

Wmax:

Total water availability for irrigation (m³) (e.g., Wmax=300×106

m³).

Hmax:

Maximum usable area for cultivation (ha) (e.g., Hmax=90,000

ha).

pi: Average income

per tourist in province i (USD/tourist).

eiT: Associated jobs

per tourist in province i (jobs/tourist).

eiA: Associated jobs

per ton of oil produced in province i (jobs/ton).

ciT: CO₂ emission

coefficient per tourist in province i (kg CO₂/tourist).

ciA: CO₂ emission

coefficient per ton of oil in province i (kg CO₂/ton).

capacitate: Installed tourist

capacity limit in province i (persons/day).

σ: Tourist

seasonality coefficient (decimal).

Cmax:

Maximum allowed CO₂ emissions limit (kg CO₂).

personal disponible: Total

available rural labour (jobs).

Objective

Functions of the Integrated Model

The model

incorporates multiple objective functions, each reflecting a strategic goal of

the olive oil chain. Together, they cover the five sustainability dimensions:

•

Economic-financial: profitability maximization.

• Productive: total

oil production.

• Commercial: exports and domestic demand.

• Environmental:

efficient use of resources and reduced footprint.

•

Tourism-territorial: revenues, employment and territorial valorisation.

This configuration

allows the model to simulate different policy or market priorities and to

quantify their trade-offs.

Economic (Zecon): Maximization

of Net Profit

This function

maximizes the net margin, considering sales revenues (export and domestic) and

total costs (agricultural, industrial, commercial, taxes, marketing).

Zecon=(1-texp)PexpE+PdomD-ctradQtrad-cintQint-CmktD

Technical

(Ztec):

Maximization of Total Oil Production

This objective

reflects the pursuit of productive efficiency and optimal input use, boosting

agricultural and industrial yields.

Ztec=Qtrad+Qint

Commercial-External

(Zcom-ext):

Maximization of Exported Volume

This objective

incentivizes allocating the largest possible production to external markets,

capitalizing on the quality advantage of Argentine oil and consolidating

international presence.

Zcom−ext=E

Commercial-Internal

(Zcom-int)

Maximization of

Volume Destined for the Domestic Market

This objective

seeks to increase internal olive oil consumption in Argentina, contributing to

food security and cultural product development.

Zcom−int=D

Environmental

(Zamb)

Minimization of

Environmental Impact (Water and Carbon Footprint)

This objective

focuses on reducing the value chain’s environmental impact, promoting long-term

sustainability. It is formulated as the minimization of water and energy use,

and total CO₂ emissions from both oil production and tourist activities.

Zamb=−(αtradHtrad+αintHint)−γ(βtradHtrad+βintHint)−Σi(ciT

Ti+ciAAi)

where

γ = a weighting

factor for energy.

Productive

(Zsup)

Maximization of

Olive Grove Area in Production

This objective

seeks to expand the olive agricultural frontier and rehabilitate underutilized

plantations, increasing sectoral productive potential.

Zsup=Htrad+Hint

Tourism-Revenue

(Ztur−ing)

Maximization of

Olive Oil Tourism Revenue

This function

maximizes income generated by visits to oil mills, tastings, tourist product

sales, and accommodation services.

Ztur-ing=ΣipiTi

Tourism-Employment

(Ztur-emp)

Maximization

of Rural Employment Associated with Tourism

This

objective focuses on maximizing job creation in rural areas, including guides,

accommodation, and catering staff, contributing to curbing depopulation.

Ztur−emp=Σi

(eiTTi+eiAAi)

Tourism-Territorial

Valorisation (Ztur-val)

Maximization

of Territorial Valorization

This

objective, partly qualitative, seeks to intensify the social and economic

recognition of the olive growing landscape as a heritage resource. It can be

modelled as a tourist satisfaction index, a brand score, or a weighted sum of

income per tourist and quality certifications (DOP/IG), reflecting public

appreciation for authenticity, quality, and local culture.

Restrictions of the Integrated Model

The

restrictions define the operational, resource and environmental boundaries

within which the system must operate. They ensure feasibility of the solutions

by linking production with demand, limiting land and water use, respecting

labor and capacity constraints, and capping environmental impacts. In this way,

restrictions reflect the real conditions faced by the olive oil chain and

guarantee that the scenarios generated are both consistent and applicable:

Production-Market Balance

All

oil production must be assigned to a market (internal or external), assuming no

significant stock variations.

Qtrad+Qint=D+E

Production

Limits per System

The

oil production of each system cannot exceed its potential yield per hectare.

Qtrad≤rtradHtrad

Qint≤rintHint

Water

Availability

Total

water consumption for irrigation cannot exceed the maximum available annual

allocation.

αtradHtrad+αintHint≤Wmax

Land

Availability

The

total cultivated area cannot exceed the maximum usable area.

Htrad+Hint≤Hmax

Maximum

Internal Demand

The

demand of the internal market can be limited by its maximum consumption

potential.

D≤Dmax

Installed

Tourist Capacity

The

number of tourists in each province cannot exceed the physical capacity of

local tourist infrastructures.

Ti≤Capacity

(e.g., Mendoza’s olive oil tourism providers can serve

about 2,533 people per day).

Tourist

Seasonality

The

annual tourist offer may be limited by seasonal factors, reflected by a

coefficient.

Ti≤Capacity×Operative days

CO₂

Emissions Limit

Total

emissions generated by production and tourism must not exceed a maximum

threshold, reflecting a commitment to environmental sustainability.

Σi(ciTTi+ciAAi)≤Cmax

Labour

Balance

The

total rural labour required for agricultural and tourist activities cannot

exceed the availability of personnel.

Σi(wiTTi+wiAAi)≤personal

disponible (where wiT and wiA are labour coefficients

per tourist and per ton of oil, respectively).

Budgetary

Restrictions for Tourist Investment

Investment

in tourism in each province may be limited by available financing.

Ii≤

Tourism Investment Budget

Non-Negativity

All

decision variables must be greater than or equal to zero.

Htrad,

Hint, Qtrad, Qint, D, E, M, Ti, Ii

≥0

Transformation to Goal or Weighted Model

To

solve this multi-objective programming problem, the approach of weighted goal

programming or the weighted sum of objective functions can be adopted. Goal

programming allows for the establishment of a desired level for each objective,

subsequently minimizing deviations from these targets using deviation variables

(di-,di+ ) to represent non-compliance or excess.

Alternatively,

and often more intuitively for scenario exploration, a single scalar function

can be defined as the weighted sum of all individual objective functions:

maxZtotal=ωeconZecon+ωtecZtec+ωcom-extE+ωcom-int

D+ωamb Zamb+ωsupH+ωtur-ing Ztur-ing+ωtur-empZtur-emp+ωtur-val

Ztur-val

Here,

ωk represents the weights assigned to each objective, reflecting its strategic

priority in a given scenario. It is crucial to normalize or scale the objective

functions prior to assigning weights, as their units and magnitudes vary

significantly (e.g., Zecon in millions of USD, Ztec in

thousands of tons, Zamb in millions of m³ or kg CO₂). This

normalization ensures that the weights accurately reflect the relative

importance of each objective. By adjusting these weights, this method enables

the emulation of various strategic scenarios and the identification of

efficient Pareto solutions, which represent the best possible compromises among

conflicting objectives.

Results

Descriptive Overview of the Argentine Olive Oil Sector

As described in the Introduction, Argentina is a mid-scale

producer with low domestic consumption. Building on this context, the following

overview summarizes sectoral features relevant for scenario modelling. The low

domestic consumption, despite Argentina being a producing nation, suggests

either a market failure or a lack of strategic focus on developing internal

demand. This presents one of the most significant opportunities for the

Argentine olive oil business strategy: internal consumption could potentially

increase by 500% to reach one litter per capita per year, though even this

would remain minimal compared to European averages. Globally, olive oil

consumption has seen an average annual growth of approximately 3.5% over the

last five years, indicating a favourable international trend.

In 2021, the sector’s total turnover, encompassing both internal

consumption and exports, reached US$223 million, with olive oil accounting for

57% and table olives for 43%. The predominant primary production system in

Argentina is traditional, although newer plantations have adopted more

efficient crown systems (MAGyP, 2023).

The country boasts excellent olive varieties and the potential for qualifying

specific geographical indications. The industrial oil sector comprises

approximately 120 processing establishments, which vary in size, personnel, and

performance.

For the domestic

market, which accounts for about 20% of total production, sales volume is

distributed across major regions: AMBA (Área Metropolitana de Buenos Aires)

(CABA Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires and 40 municipalities of Provincia de

Buenos Aires) (50-58%), Interior de Buenos Aires) (15%), Litoral and NEA (NEA:

Northeast Area) (10-11%), Cuyo and NOA (Nordeste Argentino) (9-10%), Córdoba

(6-7%), and the Patagonia (Patagonia: South Area) Area (3-4%). The 500cc

container is the best-selling format, comprising 89% of the market,

significantly outpacing the 1-liter container (7.4%). PET containers are the

most widely used (35-45%), followed by cans (30-35%), while glass accounts for

12-17% of sales. Approximately four brands (SolFrut/Oliovita, Nucete, AGD/

Zuelo, Laur/Fam. Millán) dominate the market as the dominant finge and the rest

integrate the competitive fringe in the mixed oligopoly structure.

Quantitative

Performance by Scenario

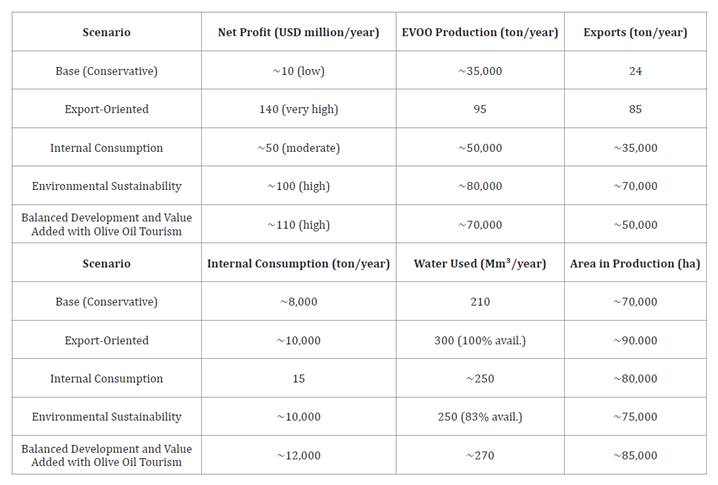

The multicriteria model quantifies the Argentine olive oil value

chain’s performance under various strategic priorities. Table 1

summarizes key outcomes: estimated annual net profit, total olive oil

production, exports, internal consumption, annual irrigation water usage, and

total cultivated area. For the balanced development and value added with olive

oil tourism scenario, values are hypothetical, showing the potential of this

integrated approach.

Table 1. Quantitative

performance by scenario.

Tabla 1. Rendimiento

cuantitativo por escenario.

A novel

contribution of this study is the quantitative inclusion of olive oil tourism

as a modelled variable. This expands traditional economic-environmental

analyses by incorporating territorial valorisation and rural employment,

aspects rarely integrated in optimization models of agri-food chains. The Base

(Conservative) scenario shows low profit (~US$10 million) from narrow margins

and low production (~35,000 tons). Most production (24,000 tons) is exported,

with minimal domestic consumption (8,000 tons). Despite not maxing out water

use, it’s inefficient, with high water consumption per ton and underutilized

capacity.

The Export-Oriented

scenario achieves the highest profit (US$140 million) by nearly tripling

production (95,000 tons) and massively increasing exports (85,000 tons). This

model uses maximum land (90,000 ha) and all available water (300 Mm³). While

water efficiency improves, domestic consumption barely rises, showing a strong

external market focus.

The Internal

Consumption scenario significantly boosts domestic availability, with 15,000

tons for local use, nearly doubling current levels. Total production rises to

50,000 tons, reducing exports to 35,000 tons. Net profit is US$50 million,

lower than the export scenario but much higher than the base. Water use (250

Mm³) is below maximum, and cultivated area reaches 80,000 ha. This approach

prioritizes the domestic market, accepting some trade-off in export revenue.

The Environmental

Sustainability scenario balances high production (80,000 tons) and exports

(70,000 tons) with substantial profit (US$100 million). Notably, it achieves

this while using 50 Mm³ less water than the export scenario, highlighting

water-saving technologies. Its water efficiency is highest, and it uses less

land (75,000 ha) for significant volume. Domestic consumption remains low. This

shows that high volumes are possible with reduced water impact, even if profit

is slightly lower due to initial costs or less aggressive resource use. It

demonstrates that a balanced approach yields broader benefits than maximizing a

single objective.

Finally, the

Balanced Development and Value Added with Olive Oil Tourism scenario offers a

well-rounded profile. With US$110 million profit, it produces 70,000 tons,

exporting 50,000 and allocating 12,000 to domestic consumption. Water use (270

Mm³) is efficient, and it uses 85,000 ha. While not maximizing any single

objective, it shows the chain’s ability to generate significant income and

rural employment through tourism, while performing strongly across production,

commerce, and environment (Guida-Johnson et al., 2024). The comparative

visualizations reinforce the multidimensional nature of trade-offs, directly

linking results to the five sustainability dimensions outlined in the

Introduction

Figure 1, visually compares

these scenarios using a radar chart, showing their relative performance across

five key areas: Economic Benefit, Total Production, Internal Consumption, Water

Efficiency, and Area Used. Each axis is normalized from 0 (worst) to 100 (best).

(Elaboration

based on the conceptual radar chart described in the source document)

Figure

1. Comparison of relative performance of strategic

scenarios on key criteria.

Figura

1. Comparación de desempeño relativo

de los escenarios estratégicos en criterios clave en las principales provincias

productoras.

The export-oriented scenario (orange line) excels in Economic

Benefit, Total Production, Area Used, and Water Efficiency, but lags in

Internal Consumption. The internal consumption scenario (red line) leads in

Internal Consumption, but scores lower in Economic Benefit and Water

Efficiency. The environmental sustainability scenario (magenta line) is

balanced, with high Water Efficiency and strong performance in Production, Area

Used, Economic Benefit, and Internal Consumption. The base scenario (yellow

line) consistently underperforms. The Balanced Development and Value Added with

Olive Oil Tourism scenario (blue line, hypothetical) shows solid, consistent

performance across all dimensions, including additional benefits from tourism

not directly shown here, like tourism revenues and rural employment. Figure

2, presents radar charts comparing the performance of Argentina’s

four main olive-producing provinces (Catamarca, La Rioja, Mendoza, and San

Juan) under different strategic scenarios.

Figure

2. Impacts of each scenario in the main producing

provinces.

Figura 2. Impactos

de cada escenario en las principales provincias productoras.

This visual analysis confirms that no single strategy is

universally best; the optimal choice depends on specific priorities. The

results also identify leverage points for improvement, particularly

technological reconversion in primary production to reduce unit costs,

diversification of products and markets to stabilize demand, and investment in

tourism infrastructure to enhance value creation. These elements extend beyond

descriptive analysis, offering actionable strategies for sectoral

competitiveness.

Iterations

and Sensitivity Analysis

While scenarios provide specific performance points, sensitivity

analysis and gradual iterations are crucial to understand how optimal solutions

shift with changing priorities or parameters, defining the Pareto frontier.

This helps answer questions about trade-offs, such as how much economic gain

must be sacrificed for water savings or increased domestic consumption.

Sensitivity

to Domestic Objective Weight (ωD)

Increasing the

importance of domestic consumption (ωD) in an export-focused model shows how production

shifts from external to local markets. Initially, small increases in domestic

consumption have minor profit impacts. However, pushing domestic consumption

beyond 12,000-15,000 tons leads to significant economic losses, as the model

must sacrifice profitable exports or expand production less efficiently. This

indicates diminishing returns for boosting internal consumption; a compromise

point around 12,000 tons allows maintaining about 75% of original exports.

Beyond this, each extra domestic ton roughly replaces an export ton, further

reducing profit. This analysis is vital for setting realistic domestic

consumption targets.

Sensitivity

to Water Limit (Wmax)

Reducing water

availability in the export-oriented model by 10% (from 300 Mm³ to 270 Mm³) cut

optimal production by about 15% and exports by 18%. This means a small water

reduction leads to a proportionally larger drop in exportable output, as the

model replaces water-intensive intensive hectares with less productive

traditional ones or leaves land uncultivated. In contrast, the environmental

sustainability scenario saw less than a 10% production drop with the same water

restriction, as it already operates efficiently. This suggests that

environmentally optimized olive growing is more resilient to water scarcity,

highlighting sustainability practices as enhancing operational resilience.

Impact of

International Price

A significant drop

in international olive oil prices (e.g., from US4,000

to US3,000 per ton) would drastically reduce the export-oriented model’s

profitability, potentially halving sectoral benefit. In such a case, the

optimal strategy would shift towards the domestic market, as the price

difference narrows. This suggests that promoting internal consumption can act

as a counter-cyclical policy, providing a stable domestic market buffer against

global price volatility (Pérez-Aleman, 2012).

Pareto

Analysis (Benefit vs. Water Footprint)

A Pareto analysis

showed that the first 50 Mm³ of additional water (from 200 to 250 Mm³)

significantly boost production and profit. However, beyond 250-260 Mm³, the

marginal profit from additional water diminishes, following the law of

diminishing returns. This indicates an optimal point where further water use

yields minimal economic gain, making water conservation highly justifiable.

Around 250-260 Mm³, conserving 40-50 Mm³ (about 15%) barely reduces maximum

profit by 5-10%. This provides a quantitative basis for sustainable water

management.

Land vs.

Technology (Intensive vs. Traditional Hectares)

Optimized model

runs consistently showed that intensive hectares (Hint)

are maximized before expanding traditional ones (Htrad),

as intensive systems are more resource efficient. Only when Hint

was artificially limited did the model expand Htrad

significantly, but this led to lower overall production and no

notable water savings. This confirms the importance of technological

reconversion: prioritizing modern, productive systems is more advantageous for

maximizing yield and efficiency than simply increasing cultivated land.

Sensitivity

to Olive Oil Tourism Integration

Integrating olive oil tourism allows evaluating how increased

tourism investment (Ii) impacts visitors (Ti), tourism revenues, rural

employment, and overall economic benefit. For example, analysing Mendoza’s

tourist capacity (approx. 2,500 people/day) reveals tourism growth potential

with infrastructure expansion or diversified offerings to reduce seasonality. A

Pareto analysis between tourism revenues and carbon footprint (including

transport emissions) would show trade-offs between tourism growth and

environmental goals. If olive oil tourism enhances brand image and quality

perception (e.g., through certifications), it could increase export

prices (Pexp) for

premium products, mitigating economic trade-offs and generating quantifiable

intangible benefits. Beyond direct revenue, tourism acts as a marketing

multiplier, boosting brand value and potentially increasing premium product

export prices, creating a virtuous cycle between tourism and product sales.

Overall, these

iterations demonstrate the multicriteria model’s sensitivity to varying

preferences and parameters, allowing a comprehensive exploration of how optimal

solutions shift with altered assumptions or strategic emphases, providing

valuable planning information. This sensitivity analysis not only validates the

robustness of the model but also supports the central hypothesis: balanced strategies

integrating economic, environmental and tourism variables yield more resilient

outcomes than single-objective approaches.

Discussion

The multicriteria

optimization results confirm the initial hypothesis: no single-objective

strategy is sufficient to ensure competitiveness and sustainability in

Argentina’s olive oil chain. Balanced approaches that integrate economic,

environmental and territorial objectives provide more resilient outcomes,

particularly under resource and price volatility. The Export-Oriented scenario

demonstrates the sector’s potential to generate high revenues yet reinforces

dependence on international markets and exposes vulnerability to price

fluctuations. Similar dynamics have been observed in Spain, where strong export

orientation has increased exposure to EU policy shifts and global price cycles

(IOC,

2015).

By contrast, the Internal Consumption scenario highlights opportunities for

domestic market development. Previous studies confirm that per capita

consumption below 0.3 litters is anomalously low for a producing country (Benencia

et al., 2014), suggesting that targeted campaigns and tax incentives could

unlock latent demand. The Environmental Sustainability scenario reveals that

water and energy-efficient technologies allow significant production while

reducing resource pressure. Comparable findings have been reported in Portugal,

where reconversion to super-intensive systems doubled yields while reducing unit

costs (Branquinho

et al., 2021). The novelty of this study lies in the Balanced Development

with Olive Oil Tourism scenario, which integrates agricultural and

service-based activities. Olive oil tourism has been qualitatively addressed in

prior works (Enolife,

2025),

but this model quantitatively demonstrates its capacity to generate revenues,

rural employment and territorial branding. From a broader perspective, the

olive oil chain should be understood as an agri-food network or “entramado”,

not just a linear chain (Díaz-Chao et al., 2016). This resonates

with bioeconomy approaches that emphasize valorisation of biomass and

by-products, ranging from pomace energy use to ecosystem services.

Incorporating this perspective enriches the interpretation of results:

scenarios that prioritize diversification, circular use of resources and

tourism services achieve more robust territorial impacts. Overall, the findings

demonstrate that policy strategies for the olive oil sector must balance

profitability, sustainability and territorial development. These results

contribute to the literature on multicriteria programming applied to agri-food

systems by explicitly incorporating tourism and territorial valorisation (Millán-Vázquez

de la Torre et al., 2017). They also provide actionable insights for public policy,

suggesting that integrated sectoral planning should foster innovation,

sustainability and experiential marketing as complementary drivers of

competitiveness. The acknowledgment of these biomass valorisation

pathways reinforces the interpretation of the olive oil chain as a bioeconomic

network, extending its impact beyond oil production toward energy,

environmental services, and territorial development.

Recommendations

Strengthen

The Domestic Market

• Increase per capita consumption (≈0.3-0.5 kg) through fiscal

incentives, educational campaigns and promotional programs.

• This provides a buffer against international price volatility.

Promote

Technological Reconversion

• Modernize groves

(super-intensive systems, mechanization, replanting).

• Reduces unit costs and improves competitiveness, following

experiences in Chile and Portugal (Vargas & Garrido, 2019).

Diversify

Products And Markets

• Expand exports beyond Brazil/USA toward emerging markets

(China, India) and regional partners (Mexico, Colombia).

• Prioritize

bottled EVOO under Argentine brands to capture more value.

Leverage

Sustainability As Opportunity

• Implement

certifications (organic, carbon-neutral, GAP).

• Access premium

markets and align with global consumer trends.

Ensure

Efficient Water Use

• Generalize technified irrigation, promote wastewater reuse and

solar-powered pumping.

• Avoid exceeding

thresholds where marginal returns diminish.

Integrate

Olive Oil Tourism Strategically

• Develop routes,

infrastructure and certified experiences.

• Generates rural

employment, strengthens territorial identity and enhances brand value.

• Promote

sustainable practices to minimize environmental trade-offs.

Conclusions

The results of the multicriteria programming model confirm that

no single-objective strategy is sufficient to ensure competitiveness and

sustainability in Argentina’s olive oil chain. Instead, a balanced approach

-integrating economic profitability, technological reconversion, environmental

sustainability and tourism- yields the most resilient outcomes under volatile

market and resource conditions. The analysis highlights three key findings:

Technological reconversion in primary production is the most effective lever

for reducing costs and improving international competitiveness. Domestic market

development is feasible up to moderate levels, strengthening resilience without

severely compromising export revenues. Olive oil tourism, when modelled

quantitatively, emerges as a central driver of value creation, rural employment

and territorial branding. These findings validate the initial hypothesis:

balanced strategies outperform purely export-oriented or consumption-focused

approaches. They also expand the literature by incorporating tourism and

territorial valorisation into an optimization framework, offering a broader

bioeconomic interpretation of value chains. Finally, the study provides

actionable insights for public policy and sectoral planning: fostering

innovation, sustainability and experiential marketing can consolidate

Argentina’s olive oil sector as a competitive and resilient player in global

markets.

Benencia, R.,

Quaranta, G., & Pedreño Cánovas, A. (2014). Mercados de trabajo,

instituciones y trayectorias en distintos escenarios migratorios. Ediciones

CICCUS.

Branquinho, S.,

Rolim, J., & Teixeira, J. L. (2021). Climate Change Adaptation Measures in

the Irrigation of a Super-Intensive Olive Orchard in the South of Portugal. Agronomy,

11(8), 1658. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11081658

CREA. (2021). Reporte

de actualidad agro. Movimiento CREA. https://proyectos.crea.org.ar/

reporte-de-actualidad-agro/

Díaz-Chao, Á.,

Sainz-González, J., & Torrent-Sellens, J. (2016). The competitiveness of

small network-firm: A practical tool. Journal of Business Research, 69(5),

1867-1872. https:// doi. org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.053

Enolife. (21 de

mayo de 2025). Mendoza ya tiene 21 almazaras y olivares que ofrecen

oleoturismo. Enolife.com.ar. https://enolife.com.ar/es/mendoza-ya-tiene-21-almazaras-y-olivares-que-ofrecen-oleoturismo-con-120-000-visitantes-al-ano/

García-Cascales, M.

S., Molina-García, A., Sánchez-Lozano, J. M., Mateo-Aroca, A., & Munier, N.

(2021). Multi-criteria analysis techniques to enhance sustainability of water

pumping irrigation. Energy Reports, 7, 4623-4632.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2021.07.026

Guida-Johnson, B.;

Vignoni, A. P.; Migale, G. M.; Aranda, M. A.; Magnano, A. 2024. Rural

abandonment and its drivers in an irrigated area of Mendoza (Argentina). Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias.

Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 56(1): 35-47. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.39.121

INDEC. (2019).

Censo Nacional Agropecuario 2018: Resultados finales.

https://www.indec.gob.ar/indec/web/Nivel4-Tema-3-8-71

International Olive

Oil Council. (2015). Estudio internacional sobre los costes de producción

del aceite de oliva.

https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/ESTUDIO-INTERNACIONAL-SOBRE-COSTES-DE-PRODUCCI%C3%93N-DEL-ACEITE-DE-OLIVA.pdf

International Olive

Oil Council. (n.d.). International Olive Oil Council. https://www.internationaloliveoil.

org/

Millán-Vázquez de

la Torre, M. G., Arjona-Fuentes, J. M., & Amador-Hidalgo, L. (2017). Olive

oil tourism: Promoting rural development in Andalusia (Spain). Tourism

Management Perspectives, 21, 100-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2016.12.003

MAGyP (Ministerio

de Agricultura, Ganadería y Pesca). (2023). Informe

síntesis. Economía regional Olivo. 1-13.

https://alimentosargentinos.magyp.gob. ar/HomeAlimentos/economias-regionales/producciones-regionales/informes/INFORME_

DE_Olivo2023.pdf

Ministerio de

Economía de la República Argentina. (2024). Informe sectorial: Olivícola (Año

9 N° 80).

https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/informe_sectorial_olivo.pdf

Pérez-Aleman, P.

(2012). Global standards and local knowledge building: Upgrading small

producers in global value chains. Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences, 109(31), 12344-12349. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1000968108

Romero, C. (1993). Teoría

de la decisión multicriterio: conceptos, técnicas y aplicaciones. Alianza

Editorial.

Stark, S.,

Biber-Freudenberger, L., Dietz, T., Escobar, N., Förster, J., Henderson, J.,

Laibach, N., Börner, J. (2022). Sustainability implications of transformation

pathways for the bioeconomy. Science Direct, 29, 215-227.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.10.011

Vargas, R., & Garrido, A. (2019). Competitiveness of

Mediterranean olive oil production: A comparative analysis of Spain and

Portugal. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research, 17(4), e0112.

https://doi.org/10.5424/sjar/2019174-14535