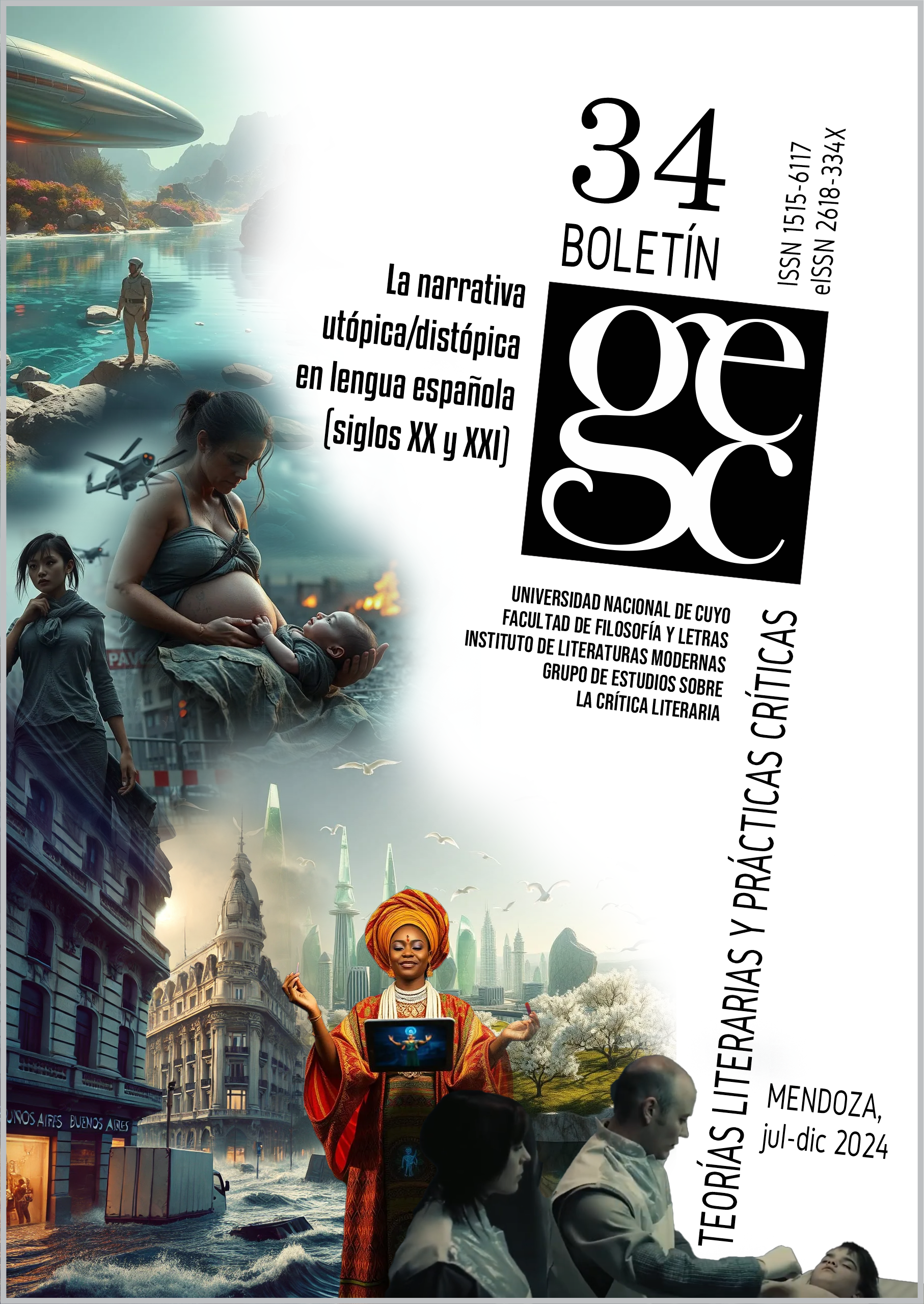

The Dys(/u)topias in Post-literary Adaptation: Radical and Concrete Utopia

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.43.071Keywords:

post-literary adaptation, fidelity, utopia, dystopia, uchronyAbstract

Radical and Concrete Utopia are two adaptations released in 2023, whose point of union is based on two key axes for the theme of this article. On the one hand, both participate in the phenomenon of post-literary adaptation, the first-one as those film stories arising from the transformation processes of the digital press and the second-one because of the cinematographic transposition from the webtoon; on the other hand, the concepts of utopia and dystopia go through the content of both narratives, although in opposite directions. While Radical proposes a dystopian scenario that evolves towards the utopian ideal, Concrete Utopia, on the other hand, proposes an utopian account that becomes post-apocalyptic dystopia. In this context, the aim of this essay is to present and analyze the dys(u)topia term, which would encompass the uchronic processes present in the case studies through the theoretical procedure of adaptation studies and the post-literary adaptation typical of the 21st century, without forgetting the eternal debate about the fidelity question.

References

Bajtín, M. M. (1989). Teoría y estética de la novela: Trabajos de investigación. (Trad. Helena S. Kriúkova y Vicente Cazcarra). Taurus.

Bell, D. (2004). Ukiyo-e Explained. Global Oriental.

Biodrowski, S. (2008, 15 de octubre). Wes Craven On Dreaming Up Nightmares. Cinefantastique. Recuperado de Archive.today. https://archive.ph/20120629063436/http://cinefantastiqueonline.com/2008/10/15/wes-craven-on-dreaming-up-nightmares/

Bloch, E. (2004). El principio esperanza (vol. 1). Trotta. (Original publicado en 1954).

Bluestone, G. (1957). Novels into Film. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Carandell, L. (1998). El periodismo, género literario. En A. van Noortwijk y A. van Haastrecht (Eds.), Periodismo y literatura (pp. 13-16). Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004484597_003

Cawelti, J. G. (1976). Adventure, Mystery, and Romance: Formula Stories as Art and Popular Culture. University of Chicago Press.

Cutchins, D. y Meeks, K. (2018). Adaptation, fidelity and reception. En D. Cutchins, K. Krebs y E. Voigts (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Adaptation (pp. 300-310). Routledge.

Davis, J. (2013, 11 de noviembre). Un nuevo método radical de aprendizaje podría desatar una generación de genios. Wired. https://www.wired.com/2013/11/aprendizaje-independiente/

Elliott, K. (2003). Rethinking the Novel/Film Debate. Cambridge University Press.

Fernández Parratt, S. (2006). Periodismo y literatura: una contribución a la delimitación de la frontera. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 12, 275-284. https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/ESMP/article/view/ESMP0606110275A/12330

Fernández Porta, E. (2007). Afterpop: La literatura de la implosión mediática. Berenice.

García Rodríguez, A. A. (2005). Cultura popular y grabado en Japón, siglos XVII a XIX. El Colegio de México.

Hutcheon, L. y Bortolotti, G. (2007). On the Origin of Adaptations: Rethinking Fidelity Discourse and ‘Success’ – Biologically. New Literary History, 38, 443-458.

Jameson, F. (2009). Arqueologías del futuro: El deseo llamado utopía y otras aproximaciones de ciencia ficción. Akal.

Leitch, T. (2004). Post-literary Adaptation. PostScript-Essays in Film and the Humanities, 23(3), 99-117.

Leitch, T. (2007). Film Adaptation & Its Discontents: From Gone with the Wind to The Passion of the Christ. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Leitch, T. (2020). Collaborating with the Dead: Adapters as Secret Agents. En B. Cronin, R. MagShamhráin y N. Preuschoff (Eds.), Adaptation Considered as a Collaborative Art: Process and Practice (pp. 19-35). Palgrave Macmillan.

Leitch, T. (2024). The Whole Hitchcock, and Nothing but the Parts. Hitchcock Annual, 27, 1-36.

Llerena Ccasani, N. (2015). Ni apellido ni rama: La Ucronía en disputa con la Ciencia Ficción en el cine de todos, algún o ningún tiempo. Foro Jurídico, 14, 209-210. https://revistas.pucp.edu.pe/index.php/forojuridico/article/view/13764

Manjoo, F. (2018, 9 de febrero). State of the Internet. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/02/09/technology/the-rise-of-a-visual-internet.html

Martorell Campos, F. (2020). Nueve tesis introductorias sobre la distopía. Quaderns de Filosofía, 7(2), 13-33. https://ojs.uv.es/index.php/qfilosofia/article/view/20287

McNair, B. (2011). Journalism at the Movies. Journalism Practice, 5(3), 366-375. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2011.564885

Murcia, A. (2014). El sentido de un comienzo: Pensamiento contrafactual, ucronía e imaginación histórica [Tesis de doctorado, Universidad Carlos III]. https://e-archivo.uc3m.es/rest/api/core/bitstreams/d49d145b-62f2-4349-a1e0-c750c872c669/content

Murray, S. (2011). The Adaptation Industry: The Cultural Economy of Contemporary Literary Adaptation. Routledge.

Nuñez Ladeveze, L. (1985). De la utopía clásica a la distopía actual. Revista de Estudios Políticos (Nueva Época), 44, 47-80.

Renouvier, C. (2019). Ucronía: La utopía en la historia. (Trad. Pilar Ruiz Va Palacios). Akal.

Soongnyung, K. (2014). Pleasant Bullying. Lezhin Comics. https://www.lezhinus.com/en

Tae-hwa, E. (Director). (2023). Concrete Utopia [Película]. Climax Studio, BH Entertainment.

Villanueva Mir, M. (2018). “De la isla a la frontera. La problematización del espacio en la ficción distópica contemporánea”. Tropelías: Revista de Teoría de la Literatura y Literatura Comparada, (29), 506-521. https://doi.org/10.26754/ojs_tropelias/tropelias.2018292083

Zalla, C. (Director). (2023). Radical [Película]. 3Pas Studios, Pantelion Films, Participant Media, EPIC Magazine, The Lift, Televisa-Univision.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2024 David Lea

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Aquellos autores/as que tengan publicaciones en esta revista, aceptan los términos siguientes:

- Los autores/as conservarán sus derechos de autor y garantizarán a la revista el derecho de primera publicación de su obra, el cual estará simultáneamente sujeto a la Licencia de reconocimiento de Creative Commons que permite a terceros compartir la obra siempre que no se use para fines comerciales, siempre que se indique su autor y su primera publicación en esta revista, y siempre que se mencionen la existencia y las especificaciones de esta licencia de uso.

- Los autores/as podrán adoptar otros acuerdos de licencia no exclusiva de distribución de la versión de la obra publicada (p. ej.: depositarla en un archivo telemático institucional o publicarla en un volumen monográfico) siempre que se indique la publicación inicial en esta revista y se cumplan las otras condiciones mencionadas arriba.

- Se permite y recomienda a los autores/as difundir su obra a través de Internet (p. ej.: en archivos telemáticos institucionales o en su página web) antes y durante el proceso de envío, lo cual puede producir intercambios interesantes y aumentar las citas de la obra publicada. (Véase El efecto del acceso abierto).