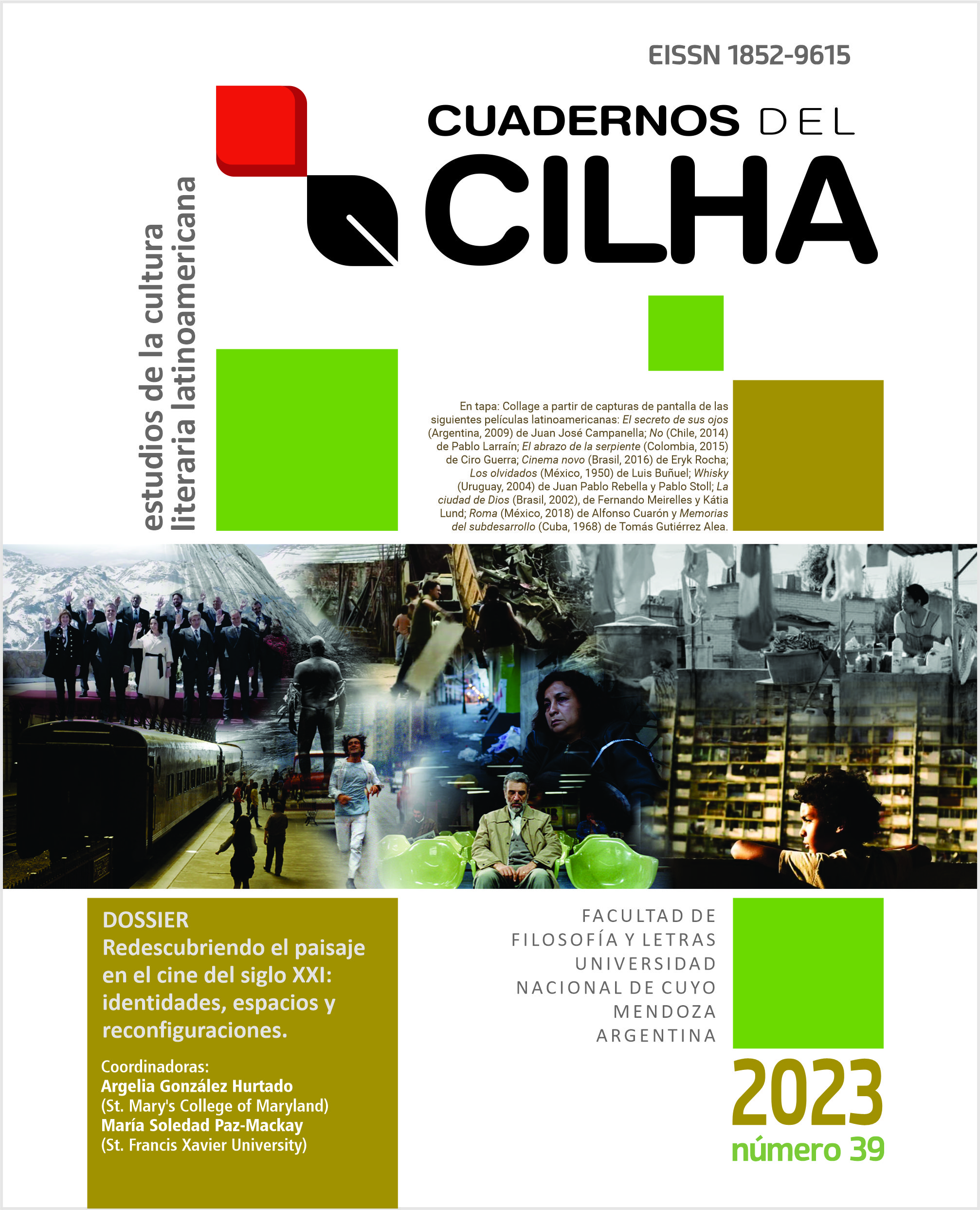

Death and landscape in La distancia más larga (The longest distance, 2013)

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.48162/rev.34.066Keywords:

landscape, death, Latin American cinemaAbstract

In La distancia más larga (The longest distance), Venezuelan director Claudia Pinto Emperador’s opera prima, death unites natural and urban spaces. Lucas, a twelve-year-old boy, flees Caracas after his mother is violently murdered. The boy’s goal is to reach la Gran Sabana, an immense area devoid of trees in the Venezuelan Amazon where the famous Mount Roraima is located. At the same time, Lucas’s grandmother returns to Venezuela. Sick with a terminal illness she intends of dying in Roraima, a place where she was happy in her youth. Constructed at first glance as a road movie, the film presents Caracas only as a setting for the actions to take place. As Lucas embarks on his journey to the Amazon, the surroundings begin to move away from their role as background for the actions and become a cinematic landscape. Here, landscape implies a specific way of registering the natural environment as an independent element of the narrative that comes to dominate the actions of the characters, sometimes stopping the narrative completely, other times slowing it down, always focusing the attention on some affective aspect. While the technical tool normally used to present landscapes is the long shot, this article explores how Pinto Emperador prefers to use editing to formulate a counterpoint of images between the city and la Gran Sabana that allows death to be incorporated in both its destructive and creative dimensions.

References

Borges, J. L. (1974). Los dos reyes y los dos laberintos. En Obras completas. Emecé.

Cohan, S. y Hark, I. R. (Eds.). (1997). The road movie book. Routledge.

Corrigan, T. (1994). A cinema without walls. Rutgers University Press.

Garibotto, V. y Pérez, J. (2016). Introduction. En V. Garibotto y J. Pérez (Eds.), The Latin American road movie (pp. 1-28). Palgrave Macmillan.

Harper, G. y Rayner J. (2010). Introduction. En G. Harper y J. Rayner (Eds), Cinema and landscape: Film, nation, and cultural geography (pp. 13-28). Intellect.

Laderman, D. (2002). Driving visions: Exploring the road movie. University of Texas Press.

Lefebvre, M. (2006). Between setting and landscape in cinema. En M. Lefebvre (Ed.), Landscape and film (pp. 19-59). Routledge.

Lefebvre, M. (2011). On Landscape in narrative cinema. Canadian Journal of Film, 20(1), Spring, 61-78.

Lie, N. (2017). The Latin American (counter-) road movie and ambivalent modernity. Palgrave Macmillan.

Lopez, D. (1993). Films by genre. 775 Categories, Styles, Trends and Movements Defined, With a Filmography for Each. Mcfarland Publishers.

Pinto Emperador, C. (Directora). (2013). La distancia más larga [Película]. SinRodeos Films.

Ranger, P. (2013). Compte rendu de [Amérique latine: stupeur et tremblements/ La distancia más larga, Venezuela/ Espagne/ Workers, Mexique/ Allemagne/ Azul y no tan rosa, Venezuela/ Espagne]. Séquences, (287), 22-23.

Rondón, M. (Directora). (2013). Pelo malo [Película]. Sudaca Films.

Salles, W. (Director). (2004) Diarios de motocicleta [Película]. FilmFour.

Sargeant, J. y Watson, S. (Eds.). (1999). Lost highways: An illustrated history of road movies. Creation.

Scott, R. (Director). (1991). Thelma & Lousie [Película]. MGM.